Whether Walter Gropius, the founder of Bauhaus and a propagandist of industrial era architecture, would have risen to expectations as a car designer is another matter. It is, after all, a highly specialized affair, even if an architect of stature could certainly be expected to be conversant with exploring the creative possibilities that arise from the interplay between engineering and aesthetics. Unfortunately, on account of the Great Depression the conditions for the liaison between Gropius and Adler in the late 1920s were not exactly favorable, as was the case with the association at the same time of his friend Le Corbusier with French car manufacturer Voisin.

Gropius did at least make an attempt at it, as the advertisement from the collection of the Museum Angewandte Kunst in Frankfurt testifies. Highly effective from an advertising point of view, even then the progressive automobile was generally praised in conjunction with urban architecture “as a vehicle with cutting-edge engineering, which meets all comfort requirements, just as Frankfurt’s buildings evolved from old styles of cozy tranquility to modern functionality.” Correspondingly, in 1900 an Adler model was pictured on the Römerberg plaza in Frankfurt, with a view of the Old Town and the cathedral, the “Adler Standard 6” Gropius, however, took pride of place in front of the southern façade of the recently completed I.G. Farben building designed by Hans Poelzig. (Nowadays – the dialectics inherent in the matter seems unfathomable – it is astonishing that the trend would appear to be in the opposite direction, from functionality back to cozy tranquility, with parts of Frankfurt’s Old Town that were destroyed in the War being reconstructed in their original form.)

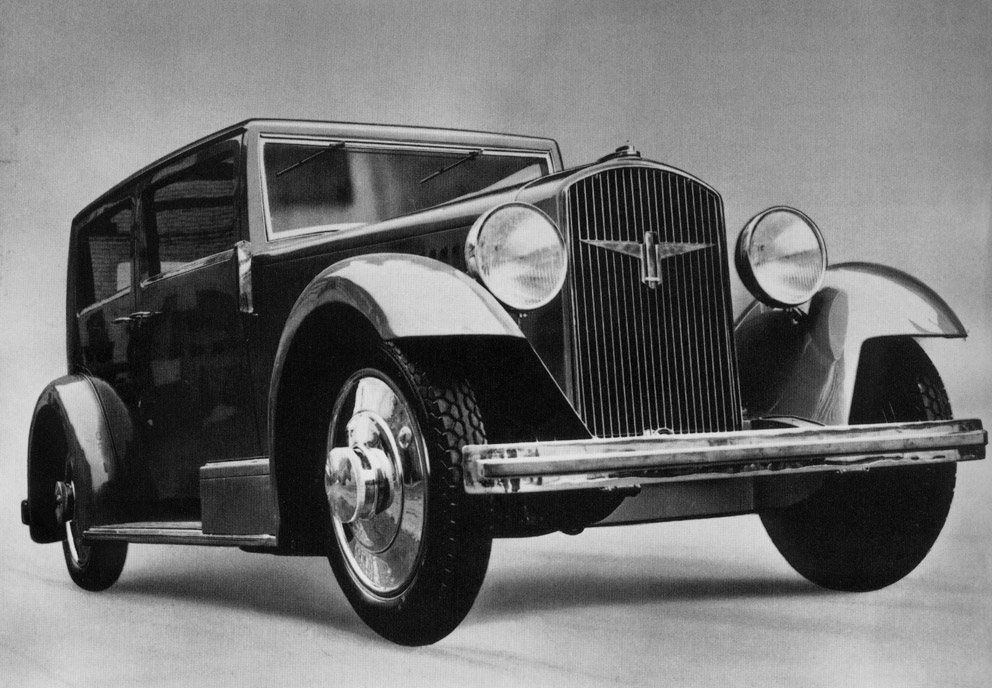

As far as the “Gropius” Adler is concerned, of which incidentally not one has survived, the facts are complex. When Gropius was working on one of his last functionalist assignments for Siemensstadt in Berlin, Adlerwerke in Frankfurt/ Main commissioned him 1929 to enhance the company’s Standard 6 and 8 models. There was a need for marketing even back then, and the name Gropius had a particularly progressive ring to it, even though little more than styling was involved. “This perfect car has been created by two names of world renown,” a poster by Bernd Reuters read accordingly. Gropius knew how to get the urbanism flywheel spinning. And thus, associated with the name Gropius, two striking, grand luxury limousines and a convertible were presented at the 1930 Salon de l’Automobile in Paris.

Despite all this, a certain Modernist logic was manifest in the link between Adler and Gropius. The Adlerwerke, originally Heinrich Kleyer AG, first produced bicycles. As early as 1889 a factory that was exemplary for the time was built in Frankfurt’s Gallus district. Having been as successful with the production of typewriters as he had been with bicycles, at the turn of the 20th century Kleyer began making cars. As early as 1914, one in five cars registered in Germany was an Adler. Henry Ford first presented his Model T – the famous “Tin Lizzie” – in 1908. From 1914 he was able to reduce its price considerably through standardization and assembly line production, which revolutionized the car market and ruined numerous producers or led to them being sold. Adlerwerke responded and in the Standard 6 developed a large series model, which was launched in 1927. It was the first German production car to feature an all-steel body, hydraulic four-wheel brakes, and parts made of ELEKTRON-light metal rather than gray cast and wrought iron, a milestone in automotive construction. The Standard 6 evolved into an entire range.

In the late 1920s Adlerwerke factory scored two coups that attracted worldwide attention: Clärenore, the daughter of the industrialist Hugo Stinnes, went round the world in a Standard 6 from 1927 till 1929, and the Director of Bauhaus in Dessau, who was friends with Heinrich Kleyer, was hired to design a model based on the Standard 6 and Standard 8. Economically the project turned out to be a flop, but the coup was effective advertising nonetheless: With an 8-cylinder inline engine, wide running boards, large Carl Zeiss headlights, gleaming chrome hub caps, a mighty hood and striking radiator grille, the luxurious Adler Gropius attracted international interest. It was featured in numerous gazettes and magazines, and made Adlerwerke world famous. As it was, Gropius’ work for Adler was not restricted to designing bodywork, he also created the martial eagle with outstretched wings typical of the era, which from 1932 on adorned the radiator bonnets of Adler models and became part of the company logo. The 1930s were the heyday of automotive production at Adler with 120.000 new cars. World War II brought the zenith to an end and the Adlerwerke Management Board decided to stop making cars in 1948. 1954 saw the end of bicycle production and in 1957 the motorcycle production stopped. In 1969 Adlerwerke was sold to the American enterprise Litton Industries and than to Volkswagen, Olivetti and Holzmann. In 1998 the typewriter production ended in Frankfurt. According to Egon R. Hanus in his records, even Mr. and Mrs. Gropius are said to have driven a later Berlin-registered Adler Cabriolet in Gropius Design convertible with the registration number IA 85337.