Every two years, Munich’s BAU takes its place alongside the other trade fairs that kick off the year. And while the Domotex and imm cologne focus on the ‘software’ in buildings, as it were, the BAU is all about the hard-hat hardware. This is also reflected in the visitors who have spent the last few days squeezing their way through the 17 halls – the fair booked a new record of more than 250,000 visitors. Yet unlike the other fairs, the BAU is pretty much free of champagne or finger food finesse. Instead, there are proper tankards of beer and Bavarian sausage, and it is grey suits who tell you all about things on their booths – most of which are hardly design-inspired. Be that as it may, built pragmatism was what the total of 2015 exhibitors mainly had to show, and “the future of building”, as the fair was subtitled, kind of disappeared behind the one façade or other. Surprising novelties tended to be rarities, while there were any number of optimized existing products. Not that this prevented us from discerning the construction industry trends.

Firstly: materials alchemy

Has great properties and is the same same...

Thanks to digital milling, printing and embossing technologies (just) about everything is possible: Materials can don shapes and colors that aren’t really theirs. Such as Alucobond by 3A Composites, which was to be seen in the guise of various prints on wood at the BAU. You could even feel the grain, but the prints only seem “genuine” from a distance. “Dekton”, the new material by Cosentino, has multi-resistant properties: It is practically indestructible, heat/damp/coldproof, and thus ideal for interiors, be it as flooring or as a façade cladding. “Dekton” consists of a combination of materials used to manufacture glass, ceramics or quartz surfaces and given such a great density through TSP (technology of sinterized particles) that just about nothing can hurt it – making the material a kind of all-round weapon for designers, albeit without a material aesthetics of its own. But it can assume the shape of sandstone, marble or deep black wood – an almost perfect illusion.

In general, things are pretty much like this with all the new materials developed or processed and now proudly on show at the BAU. However much one might admire them, it’s somehow a bit like tofu. Tofu is a great foodstuff and so incredibly flexible that you can add the taste and texture of meat or sausage. And while this may taste good, it is the food industry that benefits most: It can now create a delightful illusion for the palette at a low price. And we’ll soon see architects tapping walls again with their knuckles to check the sound and find out what is behind the wood, metal or stone texture. Not that you’re necessarily all that much smarter afterwards.

Second: always somehow new

Timelessness misunderstood

Time gnaws at buildings, products, and even us. No two ways about it. Not that we wish to accept the fact, either in our homes or in our bodies. In 30 years’ time, facades must evidently still look as if they were pristine. Which is why they get given any amount of high-tech gloss to prevent any sullying or weathering. And the new parquet floor is also if possible to remain unmarked for decades to come. For example, Bauwerk Parkett presented its new world first, “B-Protect”, a surface that offers all the advantages of classic sealed floors – and yet you can’t tell it is not natural, untreated wood. Wooden floors with a B-Protect surface need no special care, are impervious to splashes and splotches, and optimally protected against scratches, so the makers say. Or there’s the “Meteon” façade panels by Trespa – with a metallic texture that parries patina forever and ever.

This all sounds marvelously practical, but could prove to be pretty boring in the long term. Developers and architects hand responsibility for what a house looks like over to the manufacturer of the respective materials, as we no longer want to spend time caring for the building. The right way for manufacturers to respond to our thirst for a lack of commitment and for “eternal beauty” is perhaps actually to go for built-in obsolescence, meaning buildings would also have a shelf life. And once the moment comes and the materials reach expiry date, the building gets torn down and built anew. Yes, of course that flies in the face of sustainability and sparing resources. But who cares? We prefer to use rather than own, service is what counts, not things that cause us added work and if it’s supposed to look old, then we’ll buy the relevant new “vintage” products.

Third: Architects as stylists

The no-cares package

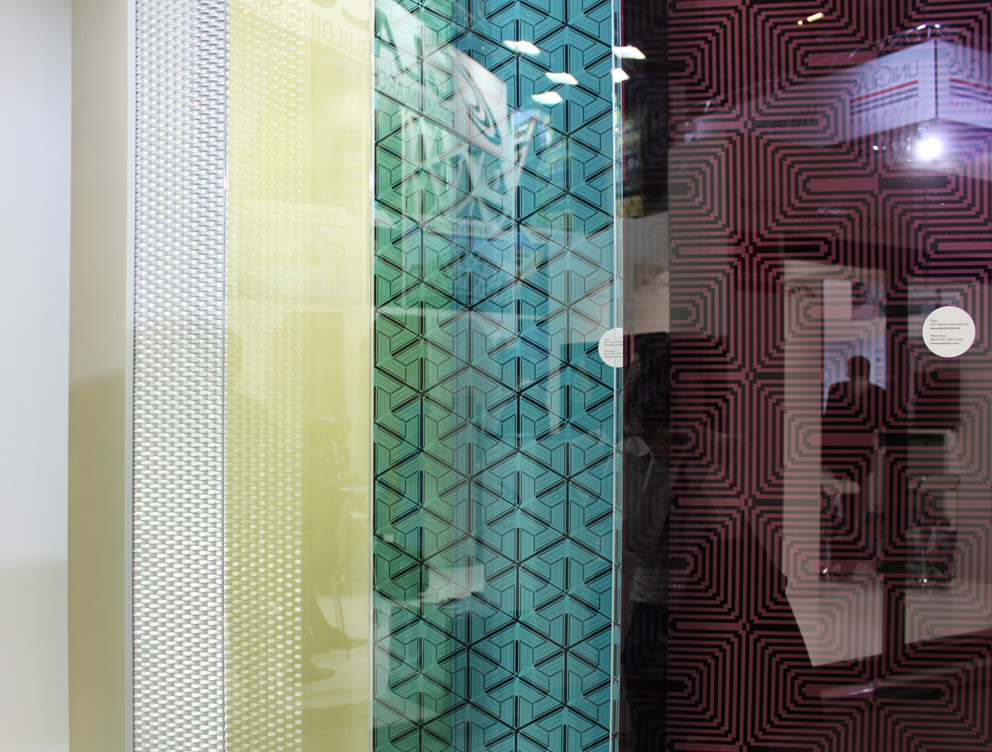

We all know that the norm in the construction industry is for every job to be fiercely fought over. Manufacturers are forced both to offer cost-effective products and if possible to avoid any risk. Added to which, rarely is there a private developer being a new build; as a rule, it’s a property developer, and he will not necessarily be interested in the context and the architecture, but more in the RoI. So we could summarize things as follows: ∑fi=0i. As in figuratively: the resulting architecture of all external forces is zero-innovative. Not exactly a calming thought. To give architects a little scope in the risk- and cost-shy industry all the same, manufacturers are developing closed systems together with no-cares packages. Take Seele’s “Iconic Skin SCF”, an integrative glass façade that essentially functions like a multifunctional, highly heat-insulating wall element. Architects can now decide what they want printed on the glass elements, the choice is anything and entirely theirs.

By contrast, Schüco goes for parametric design and wants to standardize “freeform” – with its “Schüco Parametric System”. Which has less to do with parametric designs and more with planning 3D building skins at lower cost, as the corresponding plug-in for all the usual 3D modeling software computes the components you need. It remains to be seen whether we’ll soon see freshly injected prefab house parts a la “modern homes in the parametric idiom”. Colt also offers new design options for its glass façade lamella blinds. It has joined forces here with Belectric. Together they offer architects the opportunity to design the pattern of organic PV panels themselves. Belectric supports the architects, providing advice on the resulting PV structure’s efficiency and output, Colt integrates the different systems into the glass blinds.

Ever more frequently it is such systems that are turning design workflow on its head. While the architect is still drawing the first lines he needs to know what products he wants to build – as they define the range of possibilities and thus in the final instance the design. Meaning it is no longer about be an architect and designing spaces, but about collaborating with manufacturers to develop solutions – possibly creating something new in the process; but there’s no time for that in an efficiency-driven world. On top of which sticking to styling is a pretty easy way out.

Leaving one free wish:

More experimentation please

What gets lost in the process are experiments and the wish to try out the new rather than simply adjusting things to the optimal. At Colt you find yourself staring nostalgically at the mock-up of a bio-reactor façade the company developed together with Arup and which has already won the Zumtobel Group Award. It hasn’t yet gone into mass production, though. Or Merck’s “licrivision”: a liquid crystal integrated into panes of glass that thus, to name only one example, you can adjust the glass’ transparency with the swish of a finger. Now that smacks of sci-fi, but it’s real. And Merck is busy researching the potential for architecture with the assistance of Boston architects Hoeweler + Yoon and Berlin’s Realities United.

You need such experimental projects to at least create a brief feel of the future. And they only arise if different actors pull together as a team – there was a time when interdisciplinary was the rage, so much so that it seems to have been back-seated. Sure, it all takes time and requires a free scope, not efficiency drivers. But of course that was always the case. A little more audacity when it comes to experimenting would nevertheless be great. Or, As Switzerland’s Kurt Marti once quipped: “Where would we end up if everyone said where we’d end up and no one went out to see where we would end up if we started going there.”