There is no doubt about it for the head of one particular well-known design magazine: “Design festivals are dead,” which is why his magazine no longer writes about them. And London, “the city with a reputation for being so creative, is dead too,” he claims. Apparently, none of the festivals, no matter where in the world they may be, have anything new to offer, just adaptations, variations and individual attempts to simply make a profit. Furthermore, owing to increasingly tough competition between designers, manufacturers and brands, companies are merely vying for the audience’s acceptance, nothing more.

Marketing instead of design?

This evaluation – although propounded to a small group of people in a hotel bar at a rather late hour – should not be dismissed entirely. Indeed, the “unfamiliar” is almost completely absent here; that is if you consider it to be a matter of perspective, a search for unventured paths, perhaps even for a new meaning of design. But instead you encounter new editions and handicrafts, on both a large and a small scale. Is the occupation of designer in crisis?

Allegedly the best smartphone of all time, which was launched during the London Design Festival and designed by a well-known British designer, sets itself apart from its predecessor with a connecting plug that is no longer compatible with accessories that have already been distributed by the million or with other products by the same manufacturer. Can something like this be considered good design? Or is it just great marketing? This is one of the few questions that the London Design Festival failed to discuss openly or in any great depth.

The city as framework

However, I must say that especially here in London, in late summer 2012, the ghost of the design festival feels well and truly alive. This may be down to the unexpectedly sunny weather or the Brits’ friendly nature, as we design tourists encounter at every turn. The festival is now in its tenth year; spread across the entire city it concentrates in Brompton, Clerkenwell, Covent Garden and Shoreditch and boasts everything that defines itself as creative and inventive. In contrast to Milan there is no trade fair of international relevance providing a backdrop to the festival. It is the city itself with its historical infrastructure that forms this framework, the creative backdrop. And it is not only the infinite fleet of product, graphic and multimedia design agencies, architectural firms, museums, schools and institutions whose work is palpable in the everyday buzz of the city that contribute to this unique atmosphere; they are also joined by a string of showrooms belonging to the top furniture manufacturers. There is something for everyone, from the trade fair “100%design” (the original source from which the festival flourished), to round tables, material presentations, new products from other trade fairs, historical exhibitions, workshops as well as presentations dedicated to the young blood of the design world, both large and small. Wherever you look you’ll find some kind of mixing. The logic behind the design festival is: Rummage through as much as you can, then you’ll find what you like, you’ll discover what you need, what will take you further than before.

Tradition and underground

Coming from Germany, seeing British traditionalism is always a delight. It is precisely this phenomenon that has ensured that over the past decades flailing parts of the city have been redesigned, replenished and improved, rather than simply knocked down and rebuilt. Quite the contrast to the mighty functionalism of the present-day construction industry, which is currently making a clean sweep across Germany. In line with this (at least in its interim use) a large building on New Oxford Street, built in the 1960s as a Royal Mail sorting office, was transformed into a modern event venue with a demure charm. Following a series of fashion events it is now home to “designjunction”, under the “creative direction” of Michael Sodeau. In the former post office, “mid-century” exhibiters now meet present-day companies and designers, all connected by a certain retro chic.

Exhibitors include “Das Programm”, a British design enthusiast who attentively displays rare Braun appliances and Vitsœ furniture by Dieter Rams, as well as a number of up-market 1950s second-hand dealers. Spread across three stories, products by manufacturers such as Agape, Artek, Carl Hansen, e15, Gubi or Thonet come together with presentations by designers like Bethan Gray and Benjamin Hubert. The next generation fresh from Britain’s universities also has a presence here, as does a series of designers who like to call themselves “furniture artists”. “Tent London” and “Super brands London”, based in the east of the capital, adhere to a similar principle.

Angela Merkel as bread stemp

Despite the building frenzy spurred by the Olympics, London remains a city of asynchronisms. The city is somehow resistant, it just won’t allow itself to be reinvented every day, and therefore calls for a more playful approach, for a kind of sidestepping. Take one luggage retailer in South Kensington for example, who took to presenting parts of their product range on the patio in front of the store so that they could offer a wider selection of products. Buildings also tend to expand underground here, with some interesting results. Those with converted basements provide additional levels for the major showrooms (like the Flos and Moroso flagship store built on Rosebery Avenue in 2009). Pop-up projects by young artists also follow a similar code. “Understory” is the name of the project run by a group of international designers – Catherine Aitken (Great Britain), Eva Malschaert (Netherlands) and Pia Wüstenberg (Germany/Finland). The three graduates from the Royal College of Art presented their latest furniture and interior design project in a space beneath Cromwell Place. One street across, likewise in the basement, there were – as an exception – no items of furniture to be seen. “Something Good”, a group of young Italian designers, together with fellow design teams who had already displayed their work in Milan and Lisbon took “methods” as their theme. They exhibited sources of inspiration in the form of a material wall, parts of which were transported to London from Venice by design agency Zaven. One of the rare examples of a project that at least rudimentarily sheds light on the working processes rather than the end product – in a stuffy basement.

The “Brompton Design District” organized a group exhibition entitled “Wonder Cabinets of Europe” in a somewhat downtrodden townhouse, with work by Oscar Diaz, Maria Jeglinska, Kueng Caputo, Judith Seng and Harry Thaler, to name but a few. The Greek group “Kopiaste” designed dough stamps for bread, boasting several motifs including Angela Merkel. Food design was also abundant and indeed diverse in its presence, as a relatively new field, somewhere between temporary installation, ironic project and packaging.

Splendor and misery in the showrooms

A few blocks away, things were taken to rather noble heights. Mint showed how to turn young, eclectic and decorative design into a commercial success. Not only the festival itself but also a number of its participants celebrated anniversaries this year. These included B&B Italia, which was likewise celebrating ten years in its enormous London showroom designed by John Pawson and Antonio Citterio, which looks something like a modern church nave. The anniversary was marked by the premiere of the “Tobi-Ishi” marble table by Ed Barber & Jay Osgerby. The Conran Shop also celebrated 25 years in the Michelin building on Fulham Road with the “Red” collection, whose proceeds will go to charity (Terence Conran was also awarded the London Design Medal for his life’s work). Cassina’s new showroom, designed by Piero Lissoni and located on the prestigious Brompton Road, is still a construction site. Design aficionados will have to wait until November for its inauguration. But as a foretaste of what is to come, visitors to the “Brompton Design District” were given the opportunity to win a “Tre Pezzi” armchair by Franco Albini and Franca Helg.

The well-known but until now extremely underestimated brand Arper took a rather different path. Arper’s new showroom can be found on Clerkenwell Road, opposite Vitra, close to Bulthaup, Knoll International, Kusch+Co and Wilkhahn – yet another design district. Though this is branch won’t officially open until October either. Yet the Treviso-based company has already provided visitors with a small glimpse into the space, whose purist design was created by “6a architects”. Last year, Arper, which was founded in 1989 as a leather goods company, booked sales of €43 million. Managing Director Claudio Feltrin has been at the helm of the company since 2000 and has stated that his showroom will not only be a mostly unused exhibition space, but will also take on a number of cultural functions. In line with this idea the company is currently sponsoring an exhibition at the British Council’s gallery space, with which Arper enjoys close links. Here a small show focuses on the life and work of the prominent Italian-Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi (1914-1992), who immigrated to Brazil with her husband in 1946. Working together with a foundation that manages the Bardis’ estate, Arper is now re-releasing the “Bowl” armchair, originally designed by the architects, in a limited leather edition.

More than furniture?

Yet another historical point of reference: “Design for the Real World” by Victor Papanek was first published in English over 40 years ago. Himself a designer and architect, he radically propagated simple design solutions and claimed: “There are professions that cause more damage than that of the industrial designer, but there aren’t many of them.” Now the Royal College of Art (RCA) has organized an exhibition at an RCA institute, the “Helen Hamlyn Center for Design”, featuring projects by current students modeled on the ideas of Victor Papanek, who advocated an inclusive and sustainable form of design: a venture that has spawned a series of simple yet beneficial creations. Items on display include construction site signage for the visually impaired, sustainable (i.e. energy-saving) lighting for the London district of Tower Hamlets and a visionary two-wheeled vehicle as a future mode of urban transport.

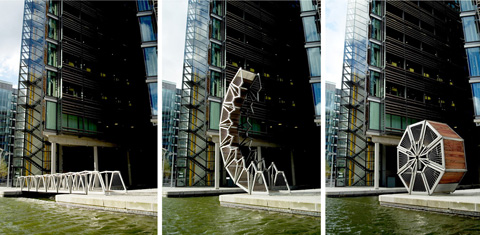

The London Design Festival began ten years ago with around thirty events and has now grown to offer 130 official program locations, which sounds much more harmless than it really is. For many of these locations hosted bundled presentations, group exhibitions, and panel discussions; a number of award ceremonies and the laying of the foundation stone for a new design museum rounded off the program. An isolated and somewhat besieged highlight was the “Heatherwick Studio – Designing the Extraordinary” exhibition in the Victoria & Albert Museum (catalog: Thomas Heatherwick – Making, Thames & Hudson, 600 pages, £30). Here too there was much more than just tables, seats and lighting on display. Neither format, material nor location seemed able to restrict Heatherwick in his creativity, who churned out sculptures, bridges, light objects, pavilions (such as the spectacular building designed for Expo Shanghai in 2010), the new, very expensive red London double-decker (“The New Routemaster”), street lighting, handbags, Christmas cards, landscape designs, overall design concepts and individual designs for high-rises as though on a whirring conveyor belt. And in doing so he pushes previously applicable quality standards to new heights.

Dead? You’ve got to be kidding! Even if the festival does try to pass off a whole lot of child’s play as design and is sometimes far from making clear what it is actually all about, whether stores selling handicrafts or strategies of refinement or indeed simplification. These urban undertones of design should encourage us to learn a little something from British composure. If nothing else, they definitely make you want to come back again.

Room divider “On Tension“ by Eva Malschaert, part of the pop-up-project “Understory”, photo © Malschaert/ Understory

Room divider “On Tension“ by Eva Malschaert, part of the pop-up-project “Understory”, photo © Malschaert/ Understory

Another project by Heatherwick from 2004 is the “Rolling Bridge“, a pedestrian bridge at the Paddington Basin, London, photo © Steve Speller

Another project by Heatherwick from 2004 is the “Rolling Bridge“, a pedestrian bridge at the Paddington Basin, London, photo © Steve Speller

The exhibition “Design for the Real Worl“ at the Royal College of Art presents student projects, such as “Sustainable Community Lighting in Tower Hamlets” by Tom Jarvis, photo © Royal College of Art

The exhibition “Design for the Real Worl“ at the Royal College of Art presents student projects, such as “Sustainable Community Lighting in Tower Hamlets” by Tom Jarvis, photo © Royal College of Art

As part of his project “Design for the Real World“, Ross Atkins improved the readability of letters at construction barricades for visually handicapped people, photo © Royal College of Art

As part of his project “Design for the Real World“, Ross Atkins improved the readability of letters at construction barricades for visually handicapped people, photo © Royal College of Art

“Advantage Austria” presentation at the “100% Design“ exhibition: The lighting objects by Doris Darling come as “pseudo-heavyweights”, photo © Thomas Edelmann

“Advantage Austria” presentation at the “100% Design“ exhibition: The lighting objects by Doris Darling come as “pseudo-heavyweights”, photo © Thomas Edelmann

A replication of Thomas Heatherwick’s Olympic cauldron for this year’s Olympic games is currently exhibited at the “Designing the Extraordinary“ exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, photo © Victoria and Albert Museum London

A replication of Thomas Heatherwick’s Olympic cauldron for this year’s Olympic games is currently exhibited at the “Designing the Extraordinary“ exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, photo © Victoria and Albert Museum London

Rear view of “New Bus for London“ by Studio Heatherwick, photo © Iwan Baan

Rear view of “New Bus for London“ by Studio Heatherwick, photo © Iwan Baan

Thomas Heatherwick and Terence Conran, photo © Conran Shop

Thomas Heatherwick and Terence Conran, photo © Conran Shop

Jasper Morrison’s “World Tape“ exhibition, photo © Thomas Edelmann

Jasper Morrison’s “World Tape“ exhibition, photo © Thomas Edelmann

Lighting objects from Pia Wüstenberg’s “Paper Productions” series, created with help of local artisans and designers in Ahmedabad, India, photo © Wüstenberg/ Understory

Lighting objects from Pia Wüstenberg’s “Paper Productions” series, created with help of local artisans and designers in Ahmedabad, India, photo © Wüstenberg/ Understory

Lina Bo Bardi’s limited edition of the “Bowl“ armchair for Arper, photo © Thomas Edelmann

Lina Bo Bardi’s limited edition of the “Bowl“ armchair for Arper, photo © Thomas Edelmann