When someone asked the American designer Johanna Grawunder which designers deserved more recognition, she answered: "All those who toil away in China and India. We don't know a single one of them". What we see of design at the major furniture fairs still seems to come primarily from the ‘First World' and thus from the major economic powers of Europe, the USA and Japan. In fact, when we put our own minds to it, we can think of only a handful of Africans, Indians, Brazilians or Chinese whom we could consider to be "star designers" in the international design circus. And this is the case despite the fact that the Internet and globalization have in the past decade or two allegedly created a greater need for cultural exchange and, true to the motto "Think global, act local", have also sharpened our creative eye for regional, craft, unconventional and traditional qualities.

Ever since the 1990s, the design avant-garde, as represented by the designers at "Droog" for example, has been incorporating regional structures and craft traditions into their designs and trying to establish them once again as sources of identity. However, in the context of the cult of the individual and fusion culture, in recent years designers, with their eye for the original and authentic, have been setting their sights on the whole world. They are impressed by foreign cultures and old craft traditions, they discover allegedly forgotten production techniques, ornaments, colors and materials that in the West had simply long been considered un-modern and were only able to survive in an environment truly remote from the design cosmos. And time and again we also see designers' enthusiasm for tradition and exotic cultures reflected in the collections of design-oriented furniture makers that would presumably have dismissed all this a few years ago as ethno kitsch. Thus the mix of cultures was also one of the key themes at this year's Milan Furniture Fair, which featured countless sofas that link cultures in the form of an east-west divan or in whose patterns the Maya meet the Space Invaders.

By way of example, for her "Fergana" collection for Moroso, Patricia Urquiola combined traditional Uzbek forms of seating furniture with Western requirements in terms of comfort and appearance. The result were luxuriant pillows covered with fabrics created using a combination of "ancient Uzbek weaving techniques and European mass production", peppered with a blend of Uzbek floral patterns and Pacman pixels. Now the Spanish designer, who lives in Italy, can unquestionably be considered the very best when it comes to mixing and sampling cultures: Not only does she constantly blend chunks of English, Italian and Spanish in her interviews, which incidentally are rather difficult to transcribe, but in her designs she likewise combines any number of forms, colors and patterns from all over the world. She designs outdoor furniture for Kettal that looks like it came from Morocco, knitted rugs with a blend of patterns for Gandia Blasco and African-looking braided stools for Driade.

the American Stephen Burks conceived the installation "M'Afrique", in which several works by African artists, architects, photographers, writers and designers were presented alongside upholstered armchairs, chairs, benches and tables produced for the company by African craftspeople - again for Moroso. In keeping with the theme, a number of Moroso classics such as Urquiola's "Lowland" or Ron Arad's "Victoria & Albert" were presented "with their style Africanized". With reference to the installation, Patricia Moroso explained the following: "Africa, with its abundance and modernity, deserves to be better known and supported in the originality of its creative expression, with which it contributes to enriching the world's cultural heritage. The African continent is extraordinarily rich in terms of expression, themes and ideas, which are for us a source of inspiration and intellectual sustenance. When applied to design, they lead to the creation of products that are able to express tradition and modernity, innovation and history, form and beauty."

Thus far, amongst all this new enthusiasm for cultural diversity, non-Western designers or studios established by groups of designers from different cultural backgrounds have only rarely been successful. British-Indian duo Doshi & Levien are now considered the paragons of the intelligent combination of opposing influences. The Indian woman Nipa Doshi and British man Jonathan Levien not only contribute their different cultural backgrounds to their joint work, but also different methods of working and approaches resulting from their respective educations at the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad and Royal College of Art in London. Their furniture and products do not represent Western design approaches to which they have simply applied an exotic pattern, for example, but rather become, as "cultural hybrids", intermediaries between classic industrial design and a lively emphasis on materiality and color, between solving problems and storytelling.

This year home living magazines everywhere announced the "multicultural furniture" trend, the "ethno-style" and "intercultural design" trend. The new color frenzy is being judged as an expression of overcoming a "design style" which is far too plain and of the need for individuality and unconventionality. The world of design seems to have opened up to foreign creative styles. Following in the footsteps of the world of fashion a couple of years late, "ethno" has arrived in furniture design and attests to a multicultural world view that wishes to pay respect to foreign cultures and traditions. And that is no little thing, when we remember that many companies understand "intercultural competence" to be simply knowing facts about symbolism and color semantics in order to ensure economic success in other cultural circles.

Yet can we really call it "intercultural design" when Hella Jongerius designs folkloric fabric wall hangings for Ikea, made by Indian seamstresses who are even allowed to immortalize themselves by adding their name to their works? Or is it rather Ikea trying to cultivate a good image, with which the oft-criticized, global home furnishing giant intends to demonstrate its responsible attitude in an act of providing development aid? And can we call it "intercultural" having Africans braid the designs of Western star designers for Moroso "in African style"?

Thus it is true to say that many projects that are currently labeled "intercultural" leave a bitter taste in our mouths. All too often they reveal a patronizing, blatantly colonial view of the exoticism of developing and threshold countries. The design monopolists probably think they have to explain the qualities of their own history to them. The cultural crossover has long been a standard theme of design magazines, in a slightly diffuse blend together with sustainability, global thinking and social responsibility. For a journalist, it is sufficient that a product is made in India for it to be considered "politically correct". Between "craft punk" and "tribal style", enthusiasm for traditional and folkloric elements frequently simply has to be seen as a fashionable trend. For ethno patterns look good on the sofa pillow especially when a little more color is in order on the balcony in summer. The oriental rug is once again permitted as a contrasting element in a plain interior, or has returned to the living room as an dyed-over response to an outdated narrow-mindedness.

"Intercultural design" as a catchphrase has become a fashionable term that is frequently used irrespective of actual intercultural cooperation and real exchange programs, such as those run by design colleges or the GTZ and CIM initiatives. It is often employed when we consider countries outside our own design field and wonder that design actually occurs there. Or when a Western designer draws inspiration from a foreign culture. However, it is only when we succeed in engaging in natural, creative cooperation that goes beyond neocolonial habitus and Western missionary zeal that we have the chance of really creating something new from the melting pot of cultures, namely, a creative attitude which is more than just the application of a pretty exotic pattern to a Western star designer's work. And with which we finally learn the names of a few more Indian, Chinese and African designers.

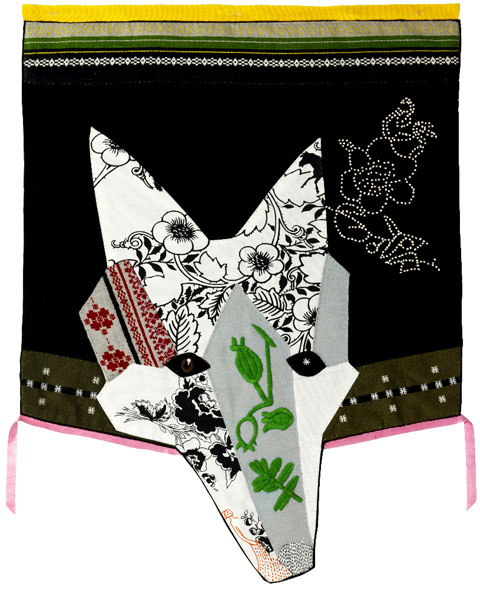

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Pelle, Mikkel and Gullspira by Hella Jongerius for IKEA PS Collection

Pelle, Mikkel and Gullspira by Hella Jongerius for IKEA PS Collection

Pelle, Mikkel and Gullspira by Hella Jongerius for IKEA PS Collection

Pelle, Mikkel and Gullspira by Hella Jongerius for IKEA PS Collection

Mangas by Patricia Urquiola for GAN by Gandia Blasco

Mangas by Patricia Urquiola for GAN by Gandia Blasco

Mangas by Patricia Urquiola for GAN by Gandia Blasco

Mangas by Patricia Urquiola for GAN by Gandia Blasco

Principessa by Doshi Levien for Moroso

Principessa by Doshi Levien for Moroso

Helix by Linko for Moroso

Helix by Linko for Moroso

Binta by Philippe Bestenheider for Moroso

Binta by Philippe Bestenheider for Moroso

Fergana by Patricia Urquiola for Moroso

Fergana by Patricia Urquiola for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Installation M’Afrique by Stephen Burks for Moroso

Pelle, Mikkel and Gullspira by Hella Jongerius for IKEA PS Collection

Pelle, Mikkel and Gullspira by Hella Jongerius for IKEA PS Collection

Pelle, Mikkel and Gullspira by Hella Jongerius for IKEA PS Collection

Pelle, Mikkel and Gullspira by Hella Jongerius for IKEA PS Collection

Pelle, Mikkel and Gullspira by Hella Jongerius for IKEA PS Collection

Pelle, Mikkel and Gullspira by Hella Jongerius for IKEA PS Collection

Mangas by Patricia Urquiola for GAN by Gandia Blasco

Mangas by Patricia Urquiola for GAN by Gandia Blasco

Mangas by Patricia Urquiola for GAN by Gandia Blasco

Mangas by Patricia Urquiola for GAN by Gandia Blasco

Mosaic by Doshi Levien for Tefal

Mosaic by Doshi Levien for Tefal

Cocoon by Moroso

Cocoon by Moroso

Flo by Patricia Urquiola for Driade

Flo by Patricia Urquiola for Driade

Fergana by Patricia Urquiola for Moroso

Fergana by Patricia Urquiola for Moroso