"Nowadays Richard Neutra is regarded as one of the most important representatives of 20th century architecture." It is sentences like this that should make us stop and think. Not that the statement is wrong, it is just that it is like a mausoleum people stopped visiting ages ago. Only those who take a closer look at a work will notice that many things to emerge from the epoch generally referred to as Modernism are full of life to this day. As such, the work of an architect like Richard Neutra also provides us not only with information about past times. The German term for being "up-to-date", Aktualität, might well be hackneyed on account of its frequent use, but it does describe a lively relationship to history which manages to overcome the ignorance of a genuinely narcissistic present.

With the exhibition "Richard Neutra in Europe. Buildings and Projects 1960 - 1970", Marta Herford has at any rate succeeded in presenting in a way that is indeed exemplary, matters historical in a fresh light. Not only because the show draws our attention to a great architect, but also because it rediscovers his largely unknown buildings in Germany, France and Switzerland - and, as such, a piece of transatlantic architectural history: ten constructed buildings, most of them villas, and seven projects that were not completed, among them the theater in Düsseldorf, are presented.

Richard Neutra, who was born in Vienna in 1892, studied under Adolf Loos, among others, and worked for Erich Mendelsohn in Berlin in the early 1920s before emigrating to the United States in 1923. Having worked in Frank Lloyd Wright's studio for a while, he advanced to become one of the leading architects in Los Angeles. In 1958 Neutra returned to Europe, initially in order to work on a holiday residence in Ascona above Lago di Maggiore. His return, however, was also a spiritual journey home to his architectural roots, and inspired him to form a clear picture of his image of America. Thus, in the 1960s, he gradually designed eight villas - two of them in Wuppertal - as well as housing developments in Walldorf near Frankfurt, and in Quickborn in Schleswig-Holstein. Richard Neutra died in 1970 in Wuppertal. He suffered a heart attack when, during a lecture tour, he was visiting the Kemper House which he had designed. Legend has it that he was extremely upset about a neighboring new building.

Confidently and as a matter of course, all of Neutra's European buildings are also variations on his typical stylistic elements: the so-called "spider legs", ceiling beams that protrude beyond the façade's outer walls and end in a support, the lamella structures which provide shade, and moreover glass corners, block fireplaces and "reflection pools", shallow expanses of water, which in our perception just as much link the interior and exterior, living space, garden and surroundings as do the large windows and mirror strips. "A properly designed building," according to Neutra, "is not a static body, but a reflection of the natural processes surrounding it and, as such, refreshment for our soul, time and again."

The show conveys all this in a vivid way. It features around one hundred original drawings of plans, draft sketches, documents, furniture design studies, historical photographs as well as some models and photographs by the Dutch photograph Iwan Baan, who documented eight of the ten buildings shown especially for the occasion, in the context of exhibition architecture featuring untreated building slabs that borrows from the open structure of Neutra's spaces without encroaching on them too much.

The extent to which Neutra explored and studied his clients' lifestyle before accepting an assignment, and the great skill he had when it came to embedding the building in its environment, once again becomes clear. For the Kemper House in Wuppertal, for example, he produced a site plan of the plot of land, on which he stuck photographs of the grounds around the building to simulate the views. Neutra admittedly did not integrate nature as such in his designs. He transformed it through architecture. Both spheres, nature and architecture, remain separate, with terraces in particular functioning as areas of transition. However, the large windows at all times allow nature - by all means in a "therapeutic" sense - to become part of the interior, where it appears in the form of a precisely composed picture. As such, Neutra not only provided solutions in the openly designed interior of the building that still hold their own today. For him, landscape and nature were far more than just surroundings. He considered them an "everlasting source of happiness".

Although Neutra's architecture is part of the "International Style", his success was primarily thanks to its individualization. It is not without reason that his private residences programmatically influenced his architecture. In 1965 Neutra wrote: "My style does not really fit in with the ‘International Style', no one can really find the niche in which my work really belongs." His villas, for example, are pervaded with a desire to merge the rationality of functionalism with a return to nature one could almost call romantic. It is no coincidence that based on anthropological findings, Neutra conceived and propagated the "bio-realistic building" which places the respect for human nature and man's natural environment above purely functional and technological considerations and makes architecture a kind of "life science".

We would have liked to find out more about this particular topic, but that would have involved a totally different exhibition concept. At any rate, by combining Richard Neutra's late European buildings with architectural photographs by Julius Shulman and the architectural models by the artist Stephan Mörsch, Marta Herford has succeeded in presenting a very special blend, which will impress any architecture enthusiast.

The recommendable catalog was published by Dumont and is available at a price of € 34.

Richard Neutra in Europe. Buildings and Projects 1960 - 1970

Until August 1, 2010

Marta Herford

www.martaherford.de

From August 20 to October 2010

Swiss Architecture Museum in Basle

www.sam-basel.org

Other stations like Deutsche Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt, Price Tower Arts Center in Oklahoma and Santa Monica Museum of Art in Kalifornien are in the planning stages.

House Rentsch (1964) by Richard Neutra © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

House Rentsch (1964) by Richard Neutra © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

BEWO Quickborn by Richard Neutra, Foto: Eberhard Troeger, Hamburg © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

BEWO Quickborn by Richard Neutra, Foto: Eberhard Troeger, Hamburg © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Casa Ebelin Bucerius, Brione sopra Minusio, Schweiz (1962-66), photo: Martin Hesse © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Casa Ebelin Bucerius, Brione sopra Minusio, Schweiz (1962-66), photo: Martin Hesse © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Casa Ebelin Bucerius, photo: Alberto Flammer, Locarno © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Casa Ebelin Bucerius, photo: Alberto Flammer, Locarno © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

BEWOBAU Walldorf Kitchen, photo: Klaus Meier-Ude, Frankfurt © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

BEWOBAU Walldorf Kitchen, photo: Klaus Meier-Ude, Frankfurt © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Haus Pescher, Foto: © Iwan Baan, Amsterdam

Haus Pescher, Foto: © Iwan Baan, Amsterdam

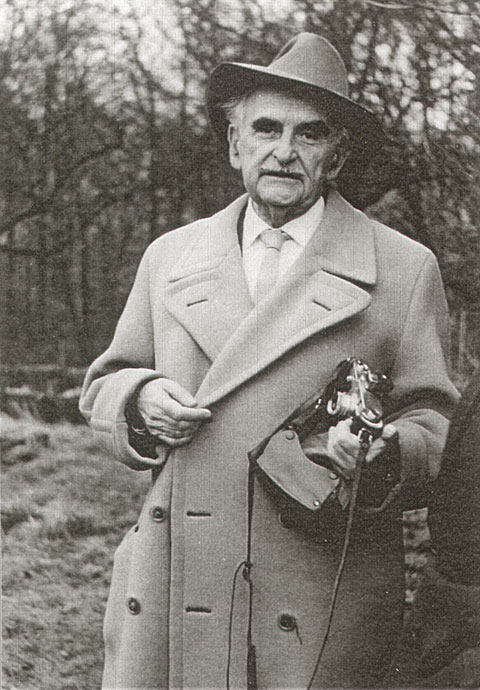

Richard Neutra

Richard Neutra

Haus Kemper by Richard Neutra, photo: Karl-Hugo Schmölz © Horst Glaeser, www.waldehuth.de

Haus Kemper by Richard Neutra, photo: Karl-Hugo Schmölz © Horst Glaeser, www.waldehuth.de

Haus Kemper by Richard Neutra, photo: Karl-Hugo Schmölz © Horst Glaeser, www.waldehuth.de

Haus Kemper by Richard Neutra, photo: Karl-Hugo Schmölz © Horst Glaeser, www.waldehuth.de

BEWO Quickborn by Richard Neutra, Foto: Eberhard Troeger, Hamburg © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

BEWO Quickborn by Richard Neutra, Foto: Eberhard Troeger, Hamburg © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Casa Ebelin Bucerius Foto: Martin Hesse © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Casa Ebelin Bucerius Foto: Martin Hesse © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Haus Rentsch (1964) by Richard Neutra © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Haus Rentsch (1964) by Richard Neutra © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

BEWOBAU Walldorf eating and living room, photo: Klaus Meier-Ude, Frankfurt © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

BEWOBAU Walldorf eating and living room, photo: Klaus Meier-Ude, Frankfurt © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Bewobau Walldorf Interieur (1960) by Richard Neutra © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Bewobau Walldorf Interieur (1960) by Richard Neutra © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

House Dr. Rudolf Sontheim by Richard Neutra © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

House Dr. Rudolf Sontheim by Richard Neutra © Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA