“I love the world of the imagination, but I love it even more when it is justified by practical sense.” Ronan Bouroullec

“I see the world around us essentially as a jungle rather than a constructed space. I like diversity, surprise, the idea of populating this jungle with quite incredible animals, creating surprises, hunting down a unique character, something that is different, and ultimately of course I seek elegance.” Erwan Bouroulec

Ronan Bouroullec, born in the French town of Quimper in 1971, is proof that art and football do not have to be mutually exclusive. As a small boy he was just as happy shooting his football into the back of the net as he was in his high school art class fervidly sketching with his pencil.

Whether his brother Erwan, five years his junior, was as avid a sportsman can’t be said for sure, but he did at any rate always share his brother’s passion for drawing. Such that Erwan’s affinity for art can by no means be described as less pronounced than Ronan’s. Perhaps it was simply that academic dedication came more easily to the younger brother, he was certainly the better of the two in Maths and Physics, spent hours happily glued to his computer screen yet always came back to tinkering around and making random things. As time went on he became fascinated by the power of vacuity, the material properties of works of Minimal Art that transcended their own materiality and the repetitive tones of Minimal music.

The oft-heard suggestion is that Ronan is the “arty one” with a hand for drawing whereas Erwan is the techie clued-up on materials and therefore ignores the sheer diversity and complexity of the duo’s talents, interests and penchants. Be that as it may, as designers both of the Bouroullec brothers are more coveted in furniture design and related fields today than ever before. So it really is quite astonishing that it has taken leading German style magazine “A&W – Architektur und Wohnen” so long to honor them with the “Designer of the Year” title.

But what is it that makes the Bouroullecs’ work so popular? Take this as a starting point: In just a few years the Breton designer duo who are clearly made of stern stuff have outstripped their rather classy, at times extravagant fellow-countryman Philippe Starck to win the favor of manufacturers and consumers alike, but why? One conceivable reason would be that Starck is somewhat more representative of the France shaped by its aristocratic tradition, while the Bouroullecs embody “la France rurale”, the down-to-earthness of the French province.

Objects full of grace

If only it were that simple. After all, you’d be pushed to claim that all of Ronan and Erwan’s products from the past years were borne of organic-looking shapes and forms, of a certain naturalness. Especially since nothing they design has a raw or even uncultivated feel about it. Quite the contrary. The things they create may have a logical stringency all of their own, yet they are subtly soft, often boasting a simple, striking and perpetual elegance. Whereby this is admittedly an elegance that emerges with not the slightest whiff of irony or morbidity, hence an elegance that does not originate in an idea or an all-encompassing culture, but has its roots in the material itself, in the purpose it was made to fulfill and in a process that has its roots in natural growth. This brings forth all those ordinary things – sofas, chairs, rugs, room dividers, each with its own distinct character. Perhaps a more accurate explanation: The Bouroullecs’ works are unpretentious in their presence, evincing great implicitness, for they are less shaped by their elegance than by their grace.

Dialectic of connection

It should be added that a special appreciation for transitions and connections is evident in all of the Bouroullecs’ works. This is as applicable to the “Algues” and “Clouds” modular systems as it is to the “Rocs” partitions or the “Steelwood” chair. A decisive factor is the conscious integration of the connections into the design itself whereby a kind of dialectic remains discernible within them, in which dichotomies are exposed without any attempt to mediate between them.

Nothing is hidden from the user; each structural element remains visible, playing its part in the finished overall appearance of the piece. Most of the Bouroullecs’ works are also nurtured by a certain mimetic impulse, shaped by the resonance of some natural shape and the endeavor to create a functioning item. Take the “Rocs” partitions for example: with the ribs and bones that are used to connect the various parts that they are a perfect demonstration of the extent to which “physis” and “tecné”, body and object, design and structure are mutually dependent. To this effect, upon first glance these “soft” stones look like exemplary specimens of a second nature, which is in abstract version of the first undertaken in order to pinpoint its quintessence in an even more succinct way.

In the case of the “Steelwood” chairs it is wood and metal as materials that like some industrial pre-product are placed in conspicuous juxtaposition and then constructively linked with one another, such that these snap-together modules revive established patterns and floral motifs in an abstract and entirely mechanized guise. “Algues” for example is both a module and model at the same time, standardized element and sprawling structure. The same can be said of “Clouds”, even though here it is much more evident that the connection to nature has taken a back seat to these technoid shapes.

The whole and its parts

Whether we’re talking about clouds, algae or stones, they are all made up of individual parts that don’t simply form a whole of their own accord. They do not come pre-assembled but require a bit of assistance. Only a hands-on approach can bring the designs to completion. If a puzzle depends upon a predefined final result that is merely hiding among the pile of tiles, the exact opposite is true of the Bouroullecs’ modules. Here it is not the final outcome that determines how one assembles the individual parts. The model that is arises from these infinite elements may be based upon a predefined logic or particular way of linking them, but the actual shape is not prefigured by these. Designed as small parts, when brought together each individual combination sets its very own tone. This can in turn lend structure to a space, dividing it up and setting boundaries, while also connecting it within these divisions and most importantly opening it up to the user as a vivid experience. As such, it is the freedom to experiment that is so predominant in these systems, the freedom to see what we can create from these (standardized) parts.

The freedom to be surprised

Perhaps this is indeed the crux of the design process and one of the secrets to the Bouroullecs’ success: Whatever they make, is made in the spirit of freedom, which leaves it up to the users to take what they are given and make something unforeseen and unexpected. Stipulations, even testing, just isn’t the Bouroullecs’ kind of thing. Indeed, when focusing on “systems” these again form the basis of a whole array of playful possibilities. They sew a garden in the midst of an unruly jungle of shapelessness. This applies to the modules just as it does to the “Self Shelf” or “Zip Carpet”, even for one of their latest designs for the office, the “Workbays”.

This spirit of freedom, which keeps things open rather than fixing them, is often associated with echoes of the provisional or nomadic. It is certainly no coincidence that Ronan and Erwan Bouroullecs’ temporary houses and shelters (Textile Pavilion, Mudam, 2006; The Stitch Room Installation, Vitra Design Museum, 2007) are reminiscent of yurts and nomadic tents.

Digitalizing the organic

At the same time, the “Facett Collection”, to name but one example, provides an indication of the power of transformation as used by the Bouroullecs’. Whereby they scour nature for fragments and patterns, subject these elements born of a natural evolutionary process to specification and digitalization, and in doing so untangle and simplify them until something new and completely distinct is born. As such the “Ploum” sofa is also something of a unicellular organism that can be found in the living room, providing both the social butterflies and social hermits among us with something to lounge on in our cocoon-like homes. Or (of course they haven’t set anything in stone here either), “Ploum”, and likewise “Quilt”, are nothing more than big, soft stones that you can sit on, though they are admittedly stones that have been structured, constructed, made.

And when the Bouroullecs transform foliage into a chair (“Osso Chair”) or why not branches (“Vegetal Chair”), then they do so in a deliberate transition from nature to culture, from growth to production. And what comes of it is precisely the opposite of lifelike and natural, rather technoid, not appearing as a romantic glorification but a pragmatic solution. This path from a natural to a technical shape is not left to pure chance but is simply routine. An object from 2006 provides a striking example: a branch complete with bark that morphs into a meticulously formed metallic bow painted in light blue.

Perhaps that is what makes the Bouroullecs so popular among manufacturers and consumers alike: The fact that they know how to subtly fuse the raw and the refined, bricolage and technical perfection, the nomadic and the settled without denying the antagonisms that continue to exist. They are indeed masters of this jovial game with nature and technology, with the shapes of nature in the first instance and their revival in the second, man-made world.

"Corniche" for Vitra, 2012, photo © Studio Bouroullec

"Corniche" for Vitra, 2012, photo © Studio Bouroullec

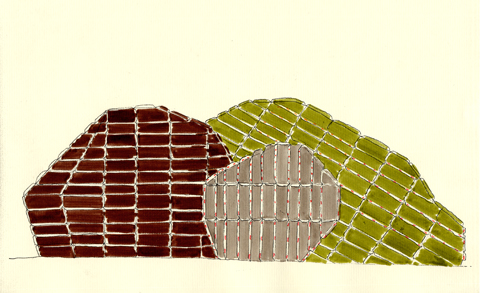

Drawings of the "ERB Series" for The Wrong Shop, 2012, photo © Studio Bouroullec

Drawings of the "ERB Series" for The Wrong Shop, 2012, photo © Studio Bouroullec

"Clouds" for Kvadrat, 2009, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"Clouds" for Kvadrat, 2009, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"Paravent" for Galerie Kreo, 2008, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"Paravent" for Galerie Kreo, 2008, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"The Stitch Room" for Vitra Design Museum , 2007, photo © Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"The Stitch Room" for Vitra Design Museum , 2007, photo © Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"Rocs" for Vitra , 2006, photo © Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"Rocs" for Vitra , 2006, photo © Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"Algues" for Vitra, 2004, photo © Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"Algues" for Vitra, 2004, photo © Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Textile pavilion for the restaurant of MUDAM, 2006, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Textile pavilion for the restaurant of MUDAM, 2006, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Office system "Joyn" for Vitra, 2002, photo © Vitra

Office system "Joyn" for Vitra, 2002, photo © Vitra

Sofa "Alcove" for Vitra, 2007, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Sofa "Alcove" for Vitra, 2007, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"Vegetal Chair" for Vitra, 2008, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"Vegetal Chair" for Vitra, 2008, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Collection „Osso" for Mattiazzi, 2012, photo © Studio Bouroullec

Collection „Osso" for Mattiazzi, 2012, photo © Studio Bouroullec

Sofa "Quilt" for Established & Sons, 2009, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Sofa "Quilt" for Established & Sons, 2009, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Studio Bouroullec, photo © Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Studio Bouroullec, photo © Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

The Bouroullec brothers, photo © Studio Bouroullec

The Bouroullec brothers, photo © Studio Bouroullec

Rug "Losanges" for Nanimarquina, 2011, photo © Studio Bouroullec

Rug "Losanges" for Nanimarquina, 2011, photo © Studio Bouroullec

"Vase" for Galerie Kreo, 2001, photo © Morgane Le Gall

"Vase" for Galerie Kreo, 2001, photo © Morgane Le Gall

Bathroom series "Bouroullec" for Axor Hansgrohe, 2010, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Bathroom series "Bouroullec" for Axor Hansgrohe, 2010, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Bathroom series "Bouroullec" for Axor Hansgrohe, 2010, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Bathroom series "Bouroullec" for Axor Hansgrohe, 2010, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Lamps "Lianes" for Galerie Kreo, 2010, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Lamps "Lianes" for Galerie Kreo, 2010, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

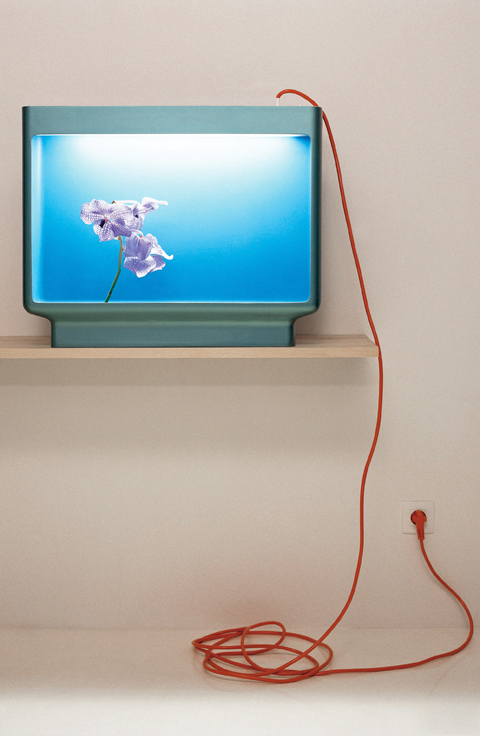

Table lamp "Lighthouse" for Established & Sons, 2010, photo © Peter Guenzel

Table lamp "Lighthouse" for Established & Sons, 2010, photo © Peter Guenzel

Table lamp "Piani" for Flos, 2011, photo © Studio Bouroullec

Table lamp "Piani" for Flos, 2011, photo © Studio Bouroullec

"Steelwood Chair" for Magis, 2007, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"Steelwood Chair" for Magis, 2007, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Sofa "Ploum" for Ligne Roset, 2011, photo © Studio Bouroullec

Sofa "Ploum" for Ligne Roset, 2011, photo © Studio Bouroullec

"Slow Chair" for Vitra, 2007, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

"Slow Chair" for Vitra, 2007, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Collection "Facett" for Ligne Roset, 2005, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec

Collection "Facett" for Ligne Roset, 2005, photo © Paul Tahon, Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec