The iPhone is a wondrous thing. In the same way that the splendid "chess Turk" was once concealed in Wolfgang von Kempelen's 18th-century chess-playing machine, the little black box is now the core of sophisticated appliances, which are presented in a display case in the "i-cosmos" show in Frankfurt's Museum for Applied Art. Apple fans have installed their gem as a control element in telephoto lenses, microphone systems or navigation instruments. Just for fun, because the effort involved is not really worth it. Digital cameras, audio recorder and GPS devices fulfill their purpose very much better - and are cheaper.

But presumably anyone who loves the Apple style must concoct such things. After all, he cannot tune a few dials, iPhone & co cannot be "tuned". Every kind of private tuning is excluded from the start thanks to the equally user-friendly and hermetic construction. Unlike moped fans, Manta drivers or normal computer freaks members of the Apple community cannot tinker with the object of their desire.

The often invoked "child in every man" must forgo his lust to play, a cultural historical break is in the offing. But help is at hand in the guise of "physical computing". The movement is spearheaded by "Arduino", an open-source a micro-controller developed by students at the Interaction Design Institute in Ivrea, Italy, which can be programmed without any specialist know-how, and if need be even without a computer. Artists use tiny apps such as "Arduino Nano" to control their video installation, textile designers implant "Lilypad" into their fabric. The latest models go by the names "Diecimila" and "Duemilanove", and recently "Arduino Mega" was launched with 128 kilobytes of memory and digital I/O ports. It is even possible to do what is meanwhile offered to children in workshops as "toy-hacking", meaning the re-functioning of manufactured products, experimental dismantling of the toy that have in the 21st century also shrunk into digital, firmly closed boxes.

There is more than just childish curiosity behind this. David Cuartielles describes the motivation of physical computing activists in arduinothedocumentary.org as "to take control back of what is inside!" It is this very insider knowledge, the source code, which Apple screens off with the touchscreen. But in Arduino everything is openly revealed, is made accessible to users, should they not choose to follow their primeval instincts and wield soldering iron or screw driver themselves.

For the time being the "self-built brand" has the design quality of a sturdy construction kit with bare cable connections and forgoes style elements such as glossy black piano varnish and similar "quality" decorative effects. But this is precisely what constitutes the spirit of the Bauhaus, which always insisted on transparency, visualized technical styling and construction methods - while today the touchscreen only feigns this "tangibility". What Apple and all the clone products of the competition took on from Bauhaus is simply decoration, the appealing, edgeless form of arbitrary shells that are changed from one season to the next.

Compared with the Apple screens studded with colored icons the interfaces even of technically advanced "Arduino" constructions such as sensing devices, laser harp or model airplane appear truly archaic, as if from a long-forgotten computer world. But for anyone who looks closer and compares, what is exuded by the icons of the apps is the pure inability to adequately visualize digital processes: video functions are embodied by an ancient television, a "box" from the 1960s. A totally normal envelope - the symbol for the customary snail mail leads to electronic mail. And for internet telephony you have the bone-shaped receiver of a phone with a lead. Is it all simply nostalgia?

No: it is aesthetics - not in a void, though but embedded in really tough market economy. The confidence-inspiring user interface that is altered for no good reason depending on the fashion trend guarantees the sale of "brand-new" models that are essentially structurally identical. This phenomenon is called "moral garb" in classic economics. In the "Lexikon der Kunst" (Art Lexicon) Communist Germany defined it as garb occasioned by a person's altered practical and ideational relationships to the respective object. Driven by the state-decreed technical euphoria Honecker's ideologist identified - "our microchips are the best!" - as the reason for the moral wear "new functional solutions" and "improvements to the utility properties". That was crude propaganda - which is now back as an artistically refined iPad advert.

The existing remnants of technical intelligence are resisting the trend. For one thing the moral wear for self-built - and thus fondly loved products is next to zero. Moreover, the dismantling and re-use of electronic components, in other words the green design recently invoked by resource waster Apple is a firm part of "physical computing". And finally even the academic world is recalling the original engineering spirit: A university institute would like its applicants for the "Activity- and Situation Identification in the Firefighting Environment" project to "not recoil at experimenting with simple electronics (e. g., Arduino)."

The i-cosmos / Power, Myth and Magic of a Brand

From 11 March to 8 May 2011

Museum for Applied Art, Frankfurt/Main

www.angewandtekunst-frankfurt.de

www.arduino.cc

Portable Media Player, iPod nano, 3rd Generation, Manufacturer: Apple 2008 Photo: © Apple

Portable Media Player, iPod nano, 3rd Generation, Manufacturer: Apple 2008 Photo: © Apple

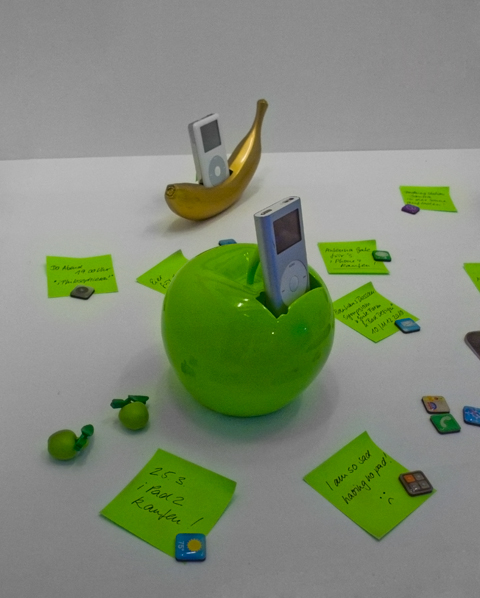

Exhibition "The i-cosmos / Power, Myth and Magic of a Brand", Museum for Applied Art, Frankfurt/Main, photos: Alejandro Mosquera

Exhibition "The i-cosmos / Power, Myth and Magic of a Brand", Museum for Applied Art, Frankfurt/Main, photos: Alejandro Mosquera

Various models of the "Game Boy", Manufacturer: Nintendo 1989 (game console), Photo: © Nintendo

Various models of the "Game Boy", Manufacturer: Nintendo 1989 (game console), Photo: © Nintendo

Photo: Strollers / Flickr

Photo: Strollers / Flickr