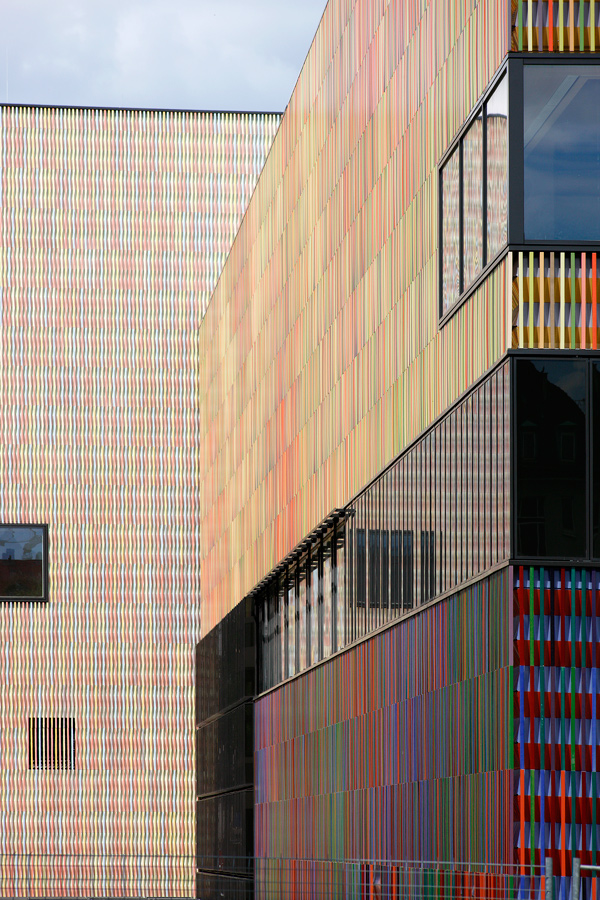

Their designs seek to fulfill the infinitude of criteria in relation to sustainability and simultaneously develop a clear aesthetic: Matthias Sauerbruch and Louisa Hutton of the Berlin architectural firm Sauerbruch Hutton have designed buildings such as Museum Brandhorst, the Federal Environment Agency in Dessau and the recently completed ADAC Head Office in Munich. They are convinced that sensuosity and passion are aspects that lend a distinct face the rather abstract quality of sustainability. Sandra Hofmeister met Matthias Sauerbruch for a talk on the topic. Sandra Hofmeister: Although one cannot deny the omnipresence of sustainability in architecture, when it comes to discussions among experts it often still find itself unable to compete aesthetics. How can the two areas be reconciled? Matthias Sauerbruch: A glance at the architectural history books shows that the common interpretation is that there are major paradigms and situations within architecture that occur again and again and in each case engender a particular architectural language. This means that as a cultural phenomenon architecture produces a response to the circumstances of the day. I strongly believe that sustainability – as a term that effectively covers anything related to climate change, be it economical energy consumption, issues surrounding overpopulation and urbanization, or the sparing use of resources – constitutes the real paradigm of the 21st century. In a similar way to artists, architects respond to the cultural, economic and social context in which they find themselves. They are simply unable to evade the theme of sustainability; quite the opposite, they are required to make an active contribution to it with the buildings they design. What could such a contribution look like in reality, when sustainability as experienced in the public arena is usually reduced to numbers and ordinances? Sauerbruch: Those who keep the overall goal in sight will strive and hope to create a building that enjoys many years of use and is well received by future generations as a building they not only use but enjoy and see a need for; such that it doesn't eventually get bulldozed but can be appreciated for as long a period as possible. It is for this reason that ventilation systems and cutting-edge construction technology alone are not enough. It is the values contained within a building that must be at the forefront of things; values that provide people with good reason to maintain a building in the long-term. People often show a great deal of commitment when it comes to preventing the demolition of a building or a neighborhood. As a general rule, this applies to buildings or neighborhoods that have a special character about them, or those, for want of a better word, that are just "pretty" and particularly appeal to the senses. There were recently discussions in Munich as to whether Kulturzentrum am Gasteig should be demolished although the building complex is barely 30 years old. Sauerbruch: This is in fact a widespread phenomenon: Buildings constructed by our parents are now perceived as weak and flawed, while those built by our grandparents on the other hand are held in much higher esteem. The greater the distance in time, the more willing we are to accept architecture. If we want to extend the half-life of architecture – and this too is an element of sustainability ... Sauerbruch: ... yes, that really is the crux of the matter! ... we should also talk about beauty and its relation to people? Sauerbruch: I believe it really is a matter of emotionality: Architecture has to appeal to people and create a kind of relationship between the object and its users. Moreover, they are of course required to offer solidity but at the same time they have to afford people flexibility. Buildings that are only geared towards one function are then faced with a problem when this function no longer exists. Therefore we have to think in structures that can adapt to suit people's respective needs. In sustainability jargon, this is often described as "news fit" – a value that calculates the probability that people will want to spend time in spaces in the longer term and as a result will want to preserve and maintain them. It is ultimately a question of cleaning, carrying out repairs and maintaining these buildings week after week. Without such passion, I don't see much of a future for a building, no matter how energy-efficient its architecture may be. So passion is also crucial for sustainability? Sauerbruch: Most definitely. Right now, we are unfortunately witness to a glut of instrumentation when it comes to sustainability. This can easily be compared with the automotive industry: A hybrid car is an instinctive and quick fix to problems associated with combustion engines and in this respect a practical path to take. However, it is in fact not that sensible at all; equipping a car with two motors and so much technology that the processes required to manufacture it consume more energy than the user will ever be able to make up by using it, even in the long term. Let's stick with the example of the automotive industry for a moment. Perhaps the most sensible thing would be to ride bicycles instead of driving cars ... Sauerbruch: ... You're right on that one (laughs) ... Now back to architecture...which then leads us to ask where the boundaries of growth and construction lie. Perhaps we should internalize them more? Sauerbruch: Now that is a difficult topic. In the housing sector, for example, the number of square meters per person has risen continuously. Even in shrinking cities, there is a growing demand for living space because people want larger, higher-quality homes. Calling for any kind of sacrifice in this respect would hardly engender a positive response. Nevertheless, the housing market will eventually come up with a clear response to rising energy costs. It may sound idealistic but I am convinced that you can use high quality to compensate for certain restrictions. Good architecture and good design can make up for a reduction in surface area and maybe even comfort too. For that to happen, a number of big changes would have to take place in our awareness of standards. Sauerbruch: In the working world in Germany, people tend to have their very own office – like a living room to themselves. But this is anything but efficient with regards to spatial usage and energy consumption. We would be better to think in terms of collective spaces where a lot of people can work together, as we see in libraries. Such spaces have the potential to create a spatial quality that distinguishes them significantly and indeed positively from individual offices which can feel more like rabbit hutches than workspaces. The boundaries of growth have in fact been known to us for some 40 years now. However, owing to the most recent financial and economic crisis they have now, together with the fears that are associated with them, become even more concrete. Would you interpret that as an opportunity or a crisis for architecture? Sauerbruch: First and for most, it is of course a crisis for architecture, simply because a lot of contracts have disappeared. At the same time, I also see it as a major opportunity. Today, we are forced to think twice about every single cent we spend and to really consider how we make use of the means available. That presents a good opportunity to scrutinize everyday categories and conventions and to move away from them. Those who don't have the money or the means, looks at construction standards and spatial necessities in a different light. And in many places a little hardship would do architecture good. www.sauerbruchhutton.de Further reading:

Colour in Architecture

by Matthias Sauerbruch und Louisa Hutton

Hardback, 288 pages, German / English

Distanz Verlag, Berlin, 2012

58.00 Euros

www.distanz.de