A silvery airship floats over the streamlined "Dymaxion Car", a compact urban auto with low fuel consumption levels. The dirigible can be used anywhere worldwide to lower lightweight towers, for example when building radio masts, wind-turbine rotors, or whatever happens to be needed at the time. And in the event of a disaster, there is a cheap and yet quite comfortable emergency shelter with a round light-metal structure that is spanned like a tent beneath a central mast. Richard Buckminster Fuller called this a "Dymaxion House", because it "dynamically" adapted to its environment, made "maximum" use of resources and was based on "tension", as opposed to the load-bearing principle that was conventionally used for buildings. In the early 1930s, the ideas promulgated by the American architect and all-round genius remained merely proposals. And now we can all enjoy examining them at "Marta" in Herford.

The advantages of the "Dymaxion Car", energy efficiency and a sparing use of resources, did not convince people in the era of gleaming chrome limousines. Three prototypes, which Buckminster managed by hook or by crook to finance, simply collected dust and ended up, in the best case, in the garage of a design collector. Now, specially for the exhibition, Norman Foster has had an impressive museum model made. The British architect has the 12 years he spent working with "Bucky" Fuller (who died in 1983) to thank for a good part of his own success – not least his idea for the dome of the Berlin Reichstag. It was Fuller's metaphor of the threatened "Spaceship Earth" that from an early date informed Foster's approach to design. Today, activists seeking to protect the climate and environmental policymakers use the catchy slogan as their own battle cry. Architects and designers concern themselves with Fuller's design idea, not only because they are astonishing in terms of structural properties, but also aesthetically stunning. Possibly in doing so they do not perceive the special qualities of Fuller, the idiosyncratic lone wolf among the reformers of this world, however.

Figures and mathematical formulae dominate in the original drawings in the exhibition, and they rarely get loaned for shows, the groundplans and elevations, but Fuller was no number-cruncher. The key experience he had as a child was when he built a little model house using peas and toothpicks, no mean achievement for an 11-year-old with a squint. Because he was quite literally unable to see right angles, little Richard simply created rows and stacks of triangles and thus came up with the basic formula for those geodetic domes that were later to become his hallmark as an adult. Albeit not in the form he preferred, namely as skins preserving the climate inside, but in the guise of white domes over radar antennae, those icons of the Cold War.

Such profane uses are not addressed in "Bucky Fuller & Spaceship Earth", an exhibition that seeks to visualize the issues and above all the linkages between physical experiments and visionary, if decidedly pragmatic thinking. Buckminster Fuller was no starry-eyed inventor, but a designer who sought to realize his ideas by building bridges between the natural sciences and playful design as well as non-applied art. Without using a PC but solely in the medium of the initially zestful sketches that gave way to ever more precise drawings.

Taking as their motto "We are all astronauts", contemporary artists have set out to trace this methodology, to continue Buckminster Fuller's formal designs and innovations as constructive opposition to the sluggish zeitgeist. In this second section of the Marta Herford twofold show, Pedro Reyes gives a new lease of life to Fuller's "Dymaxion Car" with his own "Ciclomóvil", a streamlined cycle rickshaw for metropolises threatened with eternal gridlock, and in so doing highlights Fuller's notion of "comprehensive design". Back then, only a specialist could perform such as a "synthesis of artist, inventor, mechanic, practical economist and evolutionary strategist." Today a whole dozen artists have to divide up the task among themselves. For example, there are Olafur Eliasson's decidedly practical optical mirror fencing bouts, describing the economics of attention. Tomas Saraceno proves to be an urban planning strategist with a panorama of a city over whose sea of houses geodetic domes rise up. Ai Weiwei, the artist imprisoned in China, brings the otherwise excluded political aspect back into view by rolling out the basic shape of the three-dimensional octahedron on the floor to create a threatening monument of sharp-edged brass sheets. Conversely, in the children's game of "Heaven and Hell", an octahedron made of 16 halved squares can be made simply by folding an A4-sized sheet of paper. Simon Dybbroe Möller demonstrates in his homely rattling Super-8 film how these little paper hats can dance across your four fingers as "nose tweakers" or "little salt cellars".

Here, we can sense that we must bid farewell to all the multi-media over-instrumented razzmatazz when it comes to Buckminster Fuller, as they are simply out of place. The architect never went for the overwhelming images but only for pioneering ideas. In so doing he did not set the world alight with movement, but certainly upended a few concepts that had got stuck in a rut, brought set all Platonic volumes to life. This magic of pre-computerized mathematics is visualized in Attila Csörgös' mechanical puppet theater, which has polyhedrons perform instead of the marionettes. By means of a simple metal building kit a cuboctahedron turns into an octahedron, then a tetrahedron, and finally everything reverts back to what it was.

"Bucky Fuller & Spaceship Earth" and "We are all astronauts"

Marta Herford

June 11 thru Sept. 18, 2011

www.marta-herford.de

Björn Dahlem, Galaxie (Canis Major), 2009, Installationsansicht The Island, Courtesy Galerie Guido W. Baudach, Berlin, Foto: Roman März

Björn Dahlem, Galaxie (Canis Major), 2009, Installationsansicht The Island, Courtesy Galerie Guido W. Baudach, Berlin, Foto: Roman März

Ai Weiwei, Scale No. 1, Scale No. 2, 2008, Kupfer und Edelstahl, Installationsansicht “A Few Works From Ai Weiwei”, Privatsammlung, Courtesy Alexander Ochs Galleries Berlin/Beijing

Ai Weiwei, Scale No. 1, Scale No. 2, 2008, Kupfer und Edelstahl, Installationsansicht “A Few Works From Ai Weiwei”, Privatsammlung, Courtesy Alexander Ochs Galleries Berlin/Beijing

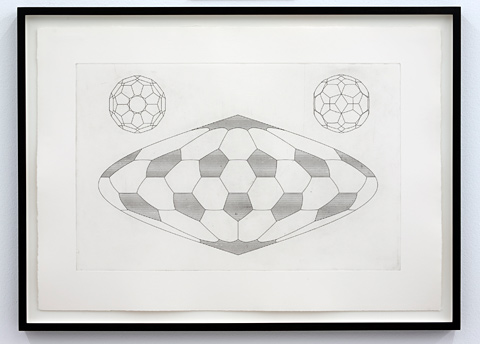

Attila Csörgő, Football World Map, 2004, Courtesy Galerija Gregor Podnar, Berlin / Ljubljana, Foto: Marcus Schneider © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2011

Attila Csörgő, Football World Map, 2004, Courtesy Galerija Gregor Podnar, Berlin / Ljubljana, Foto: Marcus Schneider © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2011

Buckminster Fuller's Dome Home

Buckminster Fuller's Dome Home

Tobias Putrih, Quasi Random, 2006, Holzstäbe, Kunststoff, 85 cm Durchmesser, Courtesy Galerija Gregor Podnar, Berlin – Ljubljana, Foto: Marcus Schneider, Foto: Marcus Schneider

Tobias Putrih, Quasi Random, 2006, Holzstäbe, Kunststoff, 85 cm Durchmesser, Courtesy Galerija Gregor Podnar, Berlin – Ljubljana, Foto: Marcus Schneider, Foto: Marcus Schneider

Olafur Eliasson, Eye see you, 2006, Sammlung Boros, Berlin, Foto: Jens Ziehe

Olafur Eliasson, Eye see you, 2006, Sammlung Boros, Berlin, Foto: Jens Ziehe

Pedro Reyes, Ciclomóvil, 2007, Aluminium, Stahl, Glasfaser, Vinyl und Fahrradmechanik, Galeria Heinrich Ehrhardt, Madrid, Foto: Luis Asin

Pedro Reyes, Ciclomóvil, 2007, Aluminium, Stahl, Glasfaser, Vinyl und Fahrradmechanik, Galeria Heinrich Ehrhardt, Madrid, Foto: Luis Asin

Sketch by Buckminster Fuller of his 4D Auto-Airplane, Courtesy The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

Sketch by Buckminster Fuller of his 4D Auto-Airplane, Courtesy The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

Beat Zoderer, Ball, 1985, Property of the artist, Foto: André Huber, Wettingen, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2011

Beat Zoderer, Ball, 1985, Property of the artist, Foto: André Huber, Wettingen, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2011

Attila Csörgő, Peeled Cube, Photo 1- 7, 1995-2001, 7 SW-Fotografien, Privatsammlung Schweiz Courtesy Galerija Gregor Podnar, Berlin / Ljubljana, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2011

Attila Csörgő, Peeled Cube, Photo 1- 7, 1995-2001, 7 SW-Fotografien, Privatsammlung Schweiz Courtesy Galerija Gregor Podnar, Berlin / Ljubljana, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2011

Buckminster Fuller & Norman Foster © Ken Kirkwood

Buckminster Fuller & Norman Foster © Ken Kirkwood

The Dymaxion Car promoting the campaign “All Out Aid to Great Britain and the Allies” Courtesy, The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

The Dymaxion Car promoting the campaign “All Out Aid to Great Britain and the Allies” Courtesy, The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

The Dymaxion Car in front of the Swiss Re Tower in London © Gregory Gibbons

The Dymaxion Car in front of the Swiss Re Tower in London © Gregory Gibbons

Foster speaks about his reconstruction of the car with Carsten Krohn. Filmed by Knut Klaßen at the opening of the exhibition „Bucky Fuller and Spaceship Earth“ at MARTa Herford, June 10th 2011.

Foster speaks about his reconstruction of the car with Carsten Krohn. Filmed by Knut Klaßen at the opening of the exhibition „Bucky Fuller and Spaceship Earth“ at MARTa Herford, June 10th 2011.

The Wichita House, Courtesy The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

The Wichita House, Courtesy The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

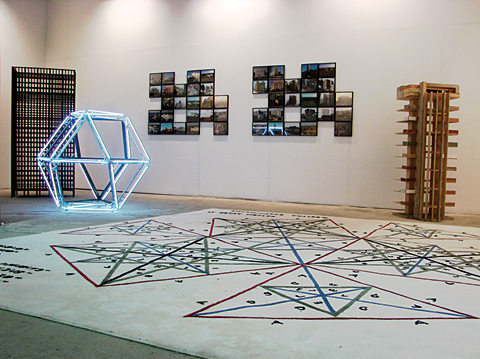

José Dávila, im Vordergrund: 25 great circles, 2007, Synthetischer Teppich, Ausstellungsansicht Travesia Cuatro Gallery MACO 07, Madrid, Collection Galeria OMR, Mexiko

José Dávila, im Vordergrund: 25 great circles, 2007, Synthetischer Teppich, Ausstellungsansicht Travesia Cuatro Gallery MACO 07, Madrid, Collection Galeria OMR, Mexiko

From the exhibition “We are all astronauts”, Attila Csörgő, Untitled (dodecahedron ≠ icosahedron), 1999, Courtesy Galerija Gregor Podnar, Berlin / Ljubljana, Foto: György Darabos, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2011

From the exhibition “We are all astronauts”, Attila Csörgő, Untitled (dodecahedron ≠ icosahedron), 1999, Courtesy Galerija Gregor Podnar, Berlin / Ljubljana, Foto: György Darabos, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2011

Pedro Reyes, Ciclomóvil, 2007, Aluminium, Stahl, Glasfaser, Vinyl und Fahrradmechanik, Galeria Heinrich Ehrhardt, Madrid, Foto: Luis Asin

Pedro Reyes, Ciclomóvil, 2007, Aluminium, Stahl, Glasfaser, Vinyl und Fahrradmechanik, Galeria Heinrich Ehrhardt, Madrid, Foto: Luis Asin

N55, Spaceframe Vehicles (Liegerad), 2011, in collaboration with Till Wolfer, Foto: N55

N55, Spaceframe Vehicles (Liegerad), 2011, in collaboration with Till Wolfer, Foto: N55

First edition of the Dymaxion Air Ocean World Map, published in Life magazine, March 1943, Courtesy, The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

First edition of the Dymaxion Air Ocean World Map, published in Life magazine, March 1943, Courtesy, The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

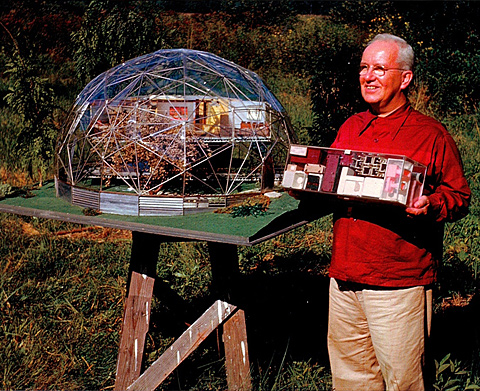

R. Buckminster Fuller with Skybreak Dome, 1949 Courtesy, The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

R. Buckminster Fuller with Skybreak Dome, 1949 Courtesy, The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

Tobias Putrih, QR Reshaping, 2003, C-Print, Courtesy Max Protetch Gallery, New York

Tobias Putrih, QR Reshaping, 2003, C-Print, Courtesy Max Protetch Gallery, New York

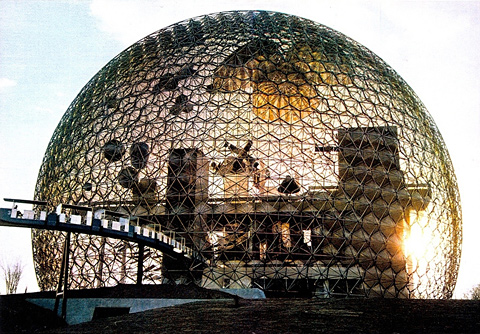

R. Buckminster Fullers US Pavillion für die Weltausstellung in Montreal, 1967 Courtesy, The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

R. Buckminster Fullers US Pavillion für die Weltausstellung in Montreal, 1967 Courtesy, The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller