Joyful and surprisingly exhilarant

It is not as though Berlin had too few concert halls. At the beginning of the year all of Hamburg was out celebrating its Elbphilharmonie, whereas Berlin could simply sit back leisurely, shrug its shoulders, and point to what is still the marvelous Philharmonic Hall by Hans Scharoun, which after all provided the vineyard-terraced role model for the Large Hall in Hamburg’s new concert building. Nevertheless Berlin is now getting its own new aural space, small, but unprecedented, in the form of the Pierre Boulez Hall at the Barenboim Said Academy in the Mitte district.

This is attributable firstly to the extraordinary concept underlying the Academy itself, a by-product of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra founded in 1999 in Weimar by Daniel Barenboim and Edward Said. The Argentine-Israeli conductor and the Palestinian-American theorist resolved that more needed to be done to foster understanding between different peoples within music, too, and therefore founded a symphony orchestra that is composed in equal part by Israeli and Arab musicians. Since its foundation the latter has very successfully toured the world. Said and Barenboim devised the parallel idea of an academy where Israelis and Arabs jointly study music and enjoy a broad humanist education into the bargain.

Once a stage-set storeroom, now an academy

To this end, the Barenboim-Said academy moved into an historical building in Berlin’s Mitte district: the former Staatsoper storehouse for stage sets on Französische Strasse, more or less between Gendarmenmarkt and Friedrichwerdersche Kirche. The listed building with its in-your-face Classicism may at first seem to be a product of the 19th century, but was in fact built in 1951-55 to designs by Richard Paulick and therefore a matter of post-War East German reconstruction. Meaning that when it first opened, the historicizing façade concealed ultra-modern stage workshops, a highly technical machine-house with all manner of stable lifting platforms, cranes and solid metal doors. From today’s angle, it could almost be described as a visionary role model, as now any number of technologically advanced museums, government buildings and department stores lurk behind copies of historicizing facades.

It was in this spirit that the conversion work was planned by HG Merz and rw+ Architekten: While the outer skin was carefully restored, the interior was addressed quite pragmatically and spaciously. A total of 2,200 cubic meters of concrete and 700 tons of steel were lugged into the old building, as the press release proudly declares. In fact, the interior was largely converted into seminar and rehearsal rooms, a library, offices and the changing rooms. The lobby was quite literally cut into the building and extends up to the eaves of the glass roof, impressively revealing the angular stair well, the old steel skeleton and the high metal sliding doors to the old workshops. Back in October the first 37 students started out on their four-year courses and in the coming year the number is set to rise to 100 scholarship-holders from all countries in the Middle East. Before that, on March 4, 2017 as part of a special festive week, the real, public focus of the academy, the Pierre Boulet Hall designed by Frank Gehry, will open its doors for the first time.

A cozy concert hall – cut into the building

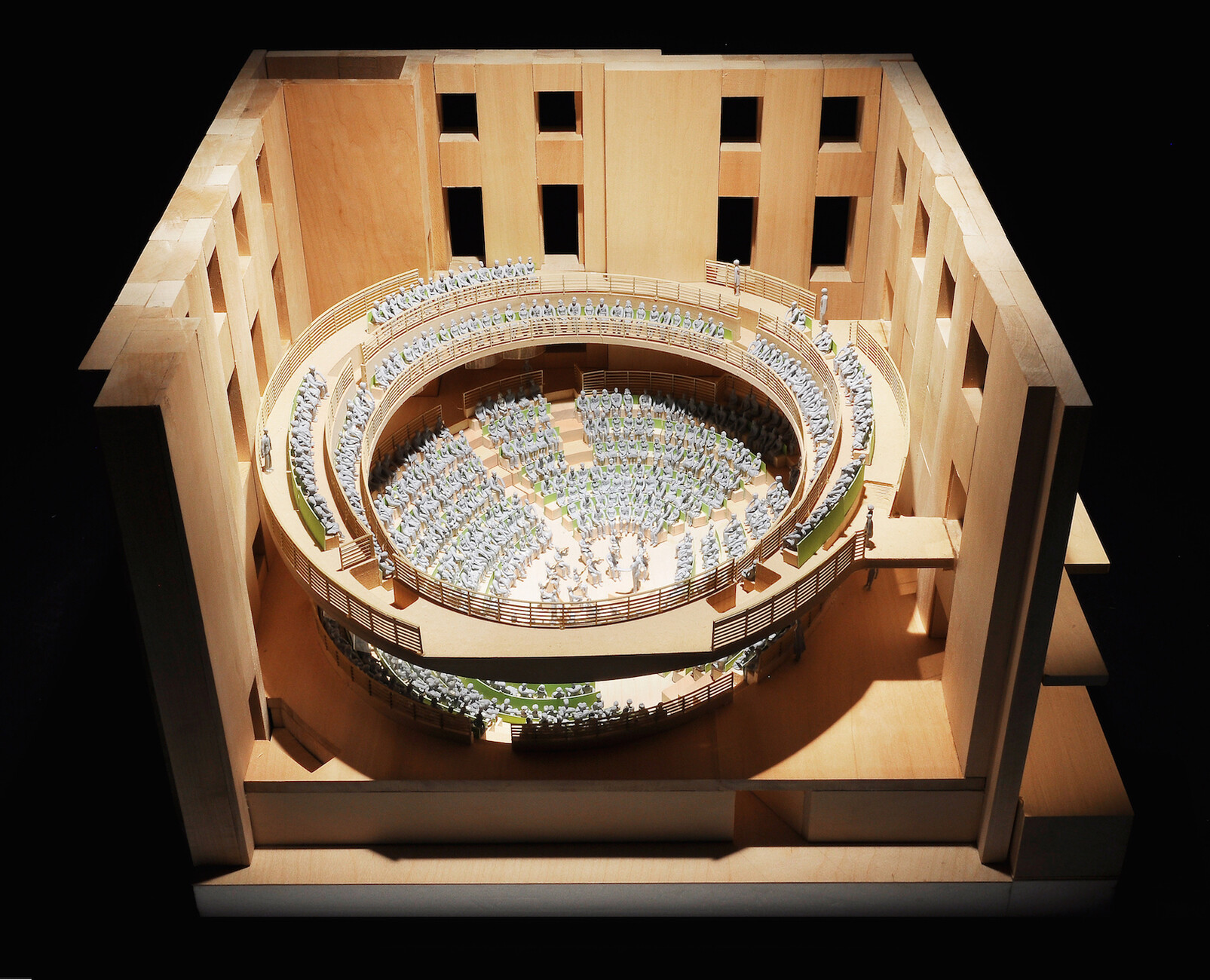

In the otherwise decidedly dark foyer, the bright wood of the wing doors seems to beckon visitors to step toward the concert hall. On entering it, one involuntarily breathes a sigh of relief. Here, no strangely bulging handkerchief shapes of titanium zinc, no steel-and-glass storm awaits you as you might have expected from the Grand Master of Deconstruction. Instead, you step into a space made of bright Douglas pine. The shapes are fractured, with hard edges, but softly curved. It is astonishingly comfy, perhaps the comfiest of any Gehry spaces. It is unclear whether this to be attributed to his Californian dotage or to the work of famous acoustics expert and concert hall specialist Yasuhisa Toyota, who was incidentally also in charge of the hall acoustics for the Elbphilharmonie. It was he, at any rate, who created the wavy wooden ceiling and the sound-absorbing floor and wall coverings.

Like the foyer, this space also seems to have been carved out of the original building. The two rows of windows show that once there were two stories here. Now the room is almost a cube, whereby the old walls and doors simply set the context for the concert hall rather than structuring it. They recede behind the dominant, oval shapes of the Gedroscher Raum, in particular behind the spectacular, curved gallery that Gehry has suspended in the hall. It is supposed to create a floating sensation, but the structural effort required worked against this. It thus hangs like a clearly perceptible weight massively in the space, instead of floating like a feather the way it does in the models. But even with no flotation it conveys a certain sense of lightness, as it is not only an oval with a large hole in the middle, but also leads slightly up and down like a mini-roller-coaster. The new shape is somehow reminiscent of Sanaa’s Learning Center in Lausanne or a softly heated slice of cheese.

The vast majority of the maximum 620 visitors will sit in the stalls, where the seating can be varied and can therefore be adapted to the particular concert or lecture setting: The audience may sit round the orchestra, or simply in orderly rows facing it. The gallery is home to only two rows of seats and the viewers in the rear row would probably have to sit on bar stools if they really wanted to see the orchestra. But it is this gallery that creates the hall’s vibrancy. The basic orthogonal pattern evaporates here and becomes merely the skin, the home for a freer form. It is almost as if the entire space oscillated slightly, started to dance. One is almost wistful on leaving a concert and stepping back out into the angular foyer.

In Berlin Gehry architecture has been limited to interiors

Who would have imagined it? The Pierre Boulez Hall is a decided joyful space and yet a decidedly restrained Gehry. He has created a space in a rectangular building that reminds us that there are other, less rigid systems of order. This brings to mind his older design in Berlin, the DG-Bank (now DZ-Bank) building, which opened in 2001 on Pariser Platz. There, strict urban planning regulations forced him into a corset of eaves height, stone façade and portrait windows. Unlike the listed Barenboim-Said Academy building, on Pariser Platz Gehry built his own cage, into the atrium of which (it runs the entire height of the building) he then unleashed a powerful explosive set of forms made of steel, glass and titanium zinc as conference rooms. Some thought it resembled the turbine of a crashed jet fighter, others spoke of a heart or a lung and Gerwin Zohlen described it as an “unimaginable object”. Perhaps Zohlen was really shocked on stepping into the atrium.

To this extent, the bank and the concert hall are kindred spirits in that both conceal a wild animal inside them. Hardly any other city in the world can claim to have popped Gehry in a box – twice. If once considers the two very different and yet similarly surprising designs, and compares them, for example, to the wild layers of ruins in Herford, Bilbao, Weil am Rhein or Los Angeles, then the tussle with spatial limits seems to have done Gehry’s architecture a lot of good. For precisely the contrast of different systems of order brings out the best in him; an astonishingly joyous sense of vertigo, and not one where, as in in Bilbao or Düsseldorf, you have to digest the disappointment that it is all a definite case of deception, and not a well-made one at that.

Incidentally, US investors are busy preparing the first Gehry that will stand in Berlin but not in a box. Construction work is already underway at Alexanderplatz for a 150-meter-high residential tower that will be the highest in Germany and with natural stone facades which, or so the rendering suggest, will stack up in great surges and incisions, turning this way, then that. You can almost hear the investors celebrating the “real Gehry” in Berlin, and we won’t really know until the high-rise opens whether it would not have been better to box it in.

Barenboim-Said-Akademie

Pierre Boulez Saal

Französische Straße 33D

10117 Berlin

The first public concert will take place on March 4, 2017 with Daniel Barenboim conducting.