Sustainability

Designing with nature

Anna Moldenhauer: Your research focuses on Baubotanik – the benefits of using the interaction of technical joints and botanical growth to form building techniques. Why do you find the topic interesting?

Prof. Ferdinand Ludwig: Baubotanik addresses architecture and trees in particular, although in the context of my professorship and the architecture practice we also work with other plant forms. What I find so interesting is the new relationship between architecture and nature, as well as with the tree as the actor in the design with all its ecological achievements, longevity, and aesthetics.

Baubotanik also encompasses the future of life in cities. In this context, do current measures such as greening facades suffice in your opinion?

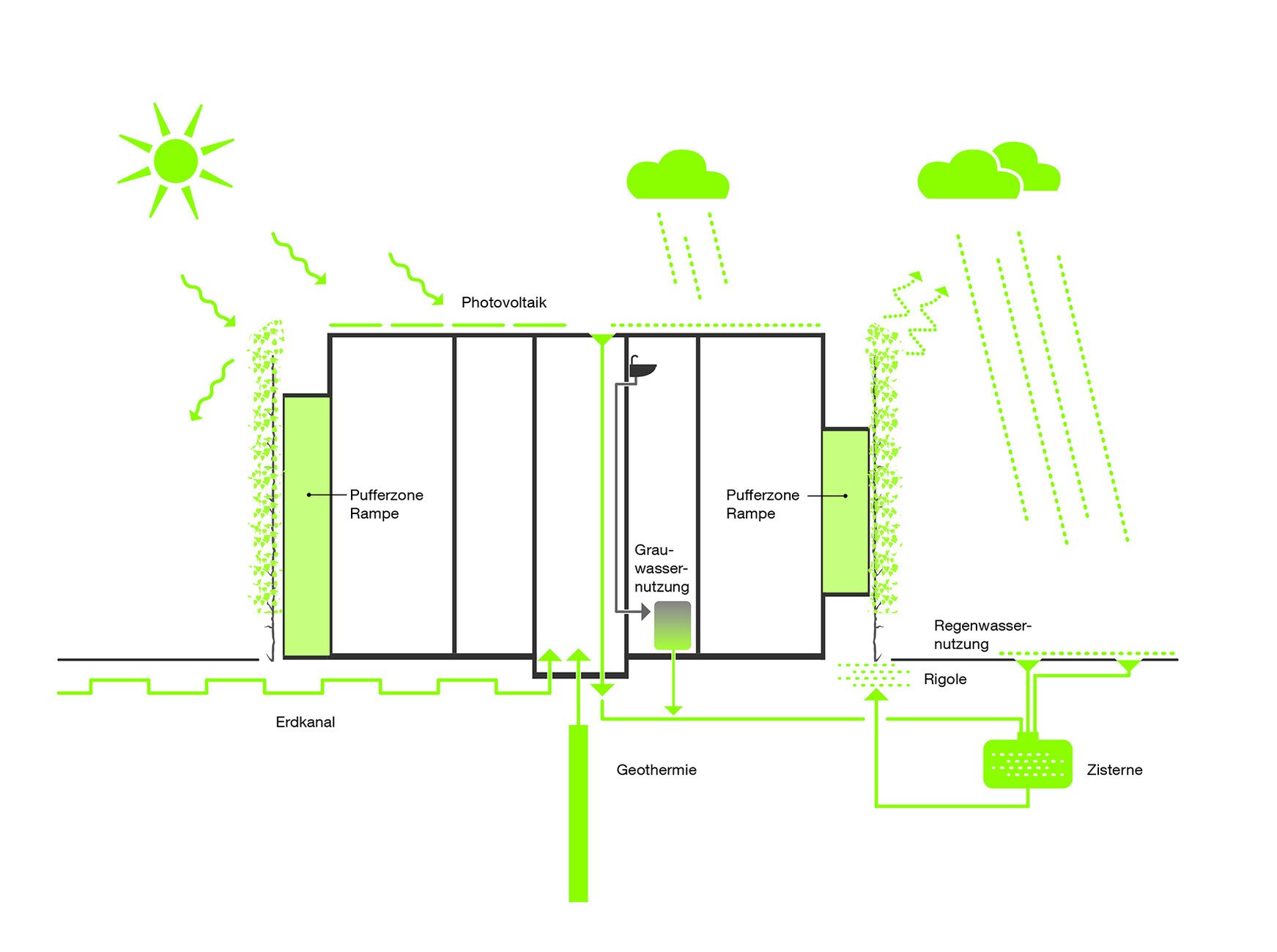

Prof. Ferdinand Ludwig: We need to distinguish here between two issues: The first is sustainability in the sense of climate protection along with sparing resources. The goal of that is to drastically reduce carbon emissions and therefore mitigate the impact of greenhouse gases. This includes photovoltaic systems, types of construction, materials – and may also involve a discussion of sufficiency, of sustainable mobility concepts, etc. The second issue is adaptation to climate change, such as how to deal with heat islands in cities. The idea is to use more urban greenery to improve people’s quality of life. With trees as an integral part of the building in a Baubotanik setting, it becomes possible, we believe, to achieve an awful lot, as the volume of greenery can provide far more shade and transpiration cooling than greening a facade. It is abundantly clear that we are far from active enough in integrating ecological qualities into architecture. The environmental disasters that we are currently experiencing will continue, and there’s a massive need for action to get our cities fit for the present and the future.

Working with the plant origins of architecture is a bit like remembering the vast body of primordial knowledge, such as the “living bridges” that indigenous peoples in the rainforests constructed down through the generations. In the book “Wachsende Architektur” that you co-wrote with Daniel Schönle, you list many impressive examples. What parts of that knowledge would you like to introduce to urban scenarios today?

Prof. Ferdinand Ludwig: We make use of these techniques as a kind of knowledge and ideas pool, but not in the sense of focusing on what once was. Rather, in those troves of past knowledge we identified strategies for co-designing with the tree: The Khasi ethnicity in India, for example, does not design a shape into which the tree will then grow, but describes an outcome that it wishes to achieve and then tries to reach that goal in a process of dialog with the tree. We are very down to earth and adopt the one or other technique, for example, and take it further with the help of digital planning tools. That is the signal difference compared to the historical role models we choose, as back then they relied very strongly on their intuitive knowledge. Since we no longer have that at our fingertips, we have to generate the insights by artificial means.

Trees take time to grow, meaning the planning has to have a long perspective – factoring in the organism’s needs and the use we hope to achieve. In parallel to this, we are seeing greater densification of cities and accelerating climate change. How do you factor such uncertainties into your plans?

Prof. Ferdinand Ludwig: In our book we highlight various different strategies for handling the factor of time. For example, plant addition: In order to swiftly generate a very large volume of greenery, many young plants are combined to form a single structure. With the right technological inputs, this can be adjusted to the pace of construction today. At the same time, we need to learn to accept the processual aspect of all of this. You are quite right to point out that we are acting in a world that is changing dynamically. Ad hoc solutions no longer work, and we cannot predict what the situation will be like in the future. What is absurd here is that the questions we ask ourselves, such as the course climate change will take, should essentially be raised for each and every architectural proposition. For example, what type of tree fits the particular situation, how water supplies will function as resources dwindle, etc., because even classic structures need to function many decades down the line. We construct buildings to fit the respective present climate, but it may be completely different in 40 years’ time. In Bavaria, drinking water is in part obtained from glacier melt. What happens if the glaciers cease to exist? What water management concept is the right one? These uncertainties need to be considered from the very outset.

”It is abundantly clear that we are far from active enough in integrating ecological qualities into architecture. The environmental disasters that we are currently experiencing will continue, and there’s a massive need for action to get our cities fit for the present and the future.“

Could you use the example of a single project to outline how it helps protect the climate and improve the quality of life for the people who live or work in the building in question?

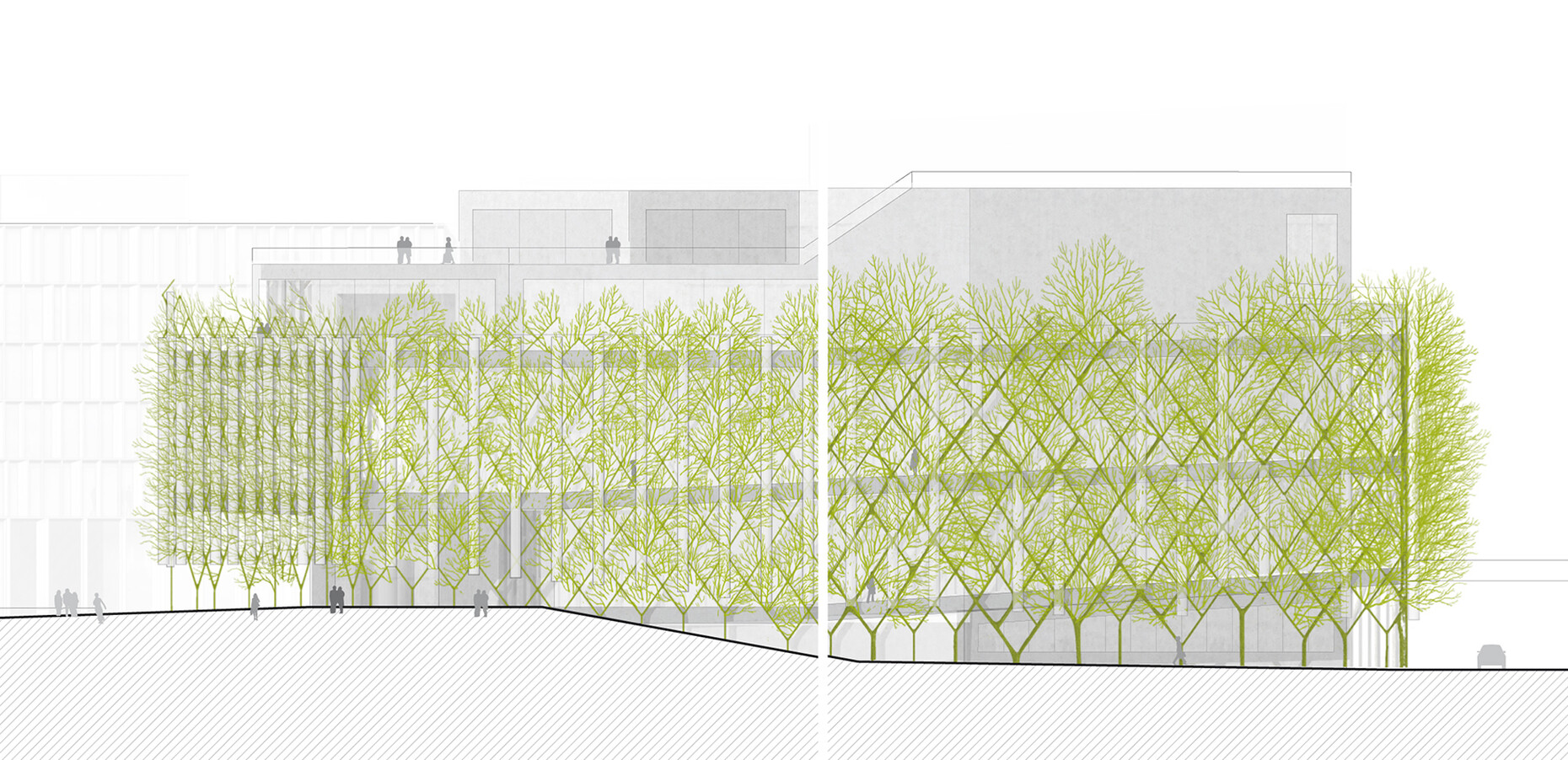

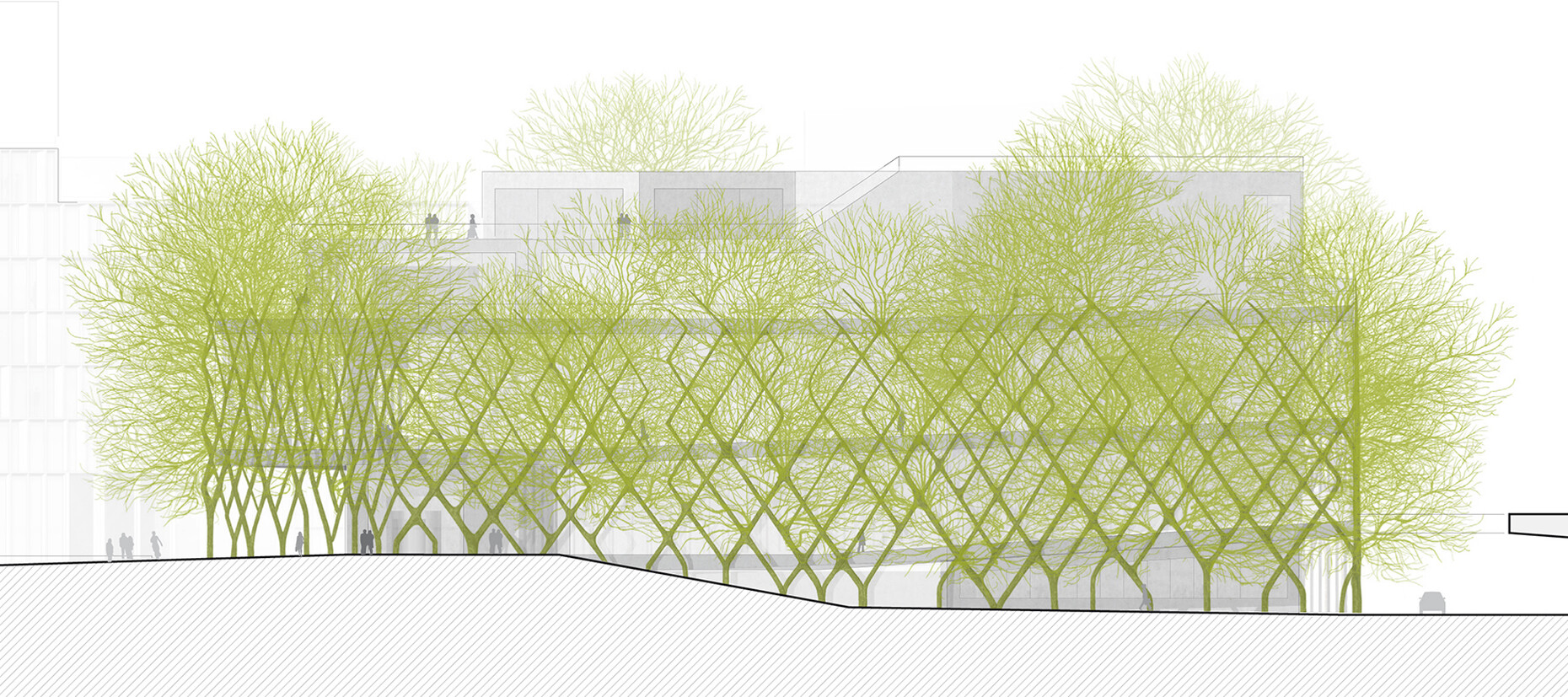

Prof. Ferdinand Ludwig: If we imagine a classic building for a moment, then we have a large built volume that heats up during the day owing to solar irradiation and absorbs a lot of thermal energy in the process. This is released with a time lag into the outer world and into the interior. The heat-island effect cannot be solved by technical means, as an air-conditioner simply releases even more heat into the environment. Shading elements may help cool the interior, but increasingly reflect the heat outwards. All that can help here are plants, because these not only provide shade but also, through tranbspiration, have a cool outer surface. In other words, the energy returns into the atmosphere through transpiration. With trees, I can achieve very differentiated shading because, unlike with classic greening of buildings that relies on two-dimensional trellises, I have the three-dimensional qualities of horizontally layered branches. And if I imagine them in front of a building, then as an inhabitant I am in the space of the tree’s canopy and at the same time protected from outside eyes and the heat. That is added ecological value, added health value, and added aesthetic value – because we believe that we are creating a natural space in the heart of the city that has so far not been considered in its architectural designs.

Greened facades tend to attract a part of nature that people don’t necessarily want to have in their living spaces, meaning birds, small animals, insects. Moreover, as time goes on, plants may die. You need to provide a lot of care in order to maintain the living aesthetics. What’s your take on that?

Prof. Ferdinand Ludwig: Introducing the topic of nature into buildings means buying an ecosystem, not a product. Roughly speaking, I am inviting plants and animals to live with me. Now there are plant and animal species that have a positive impact on people and those that provide so-called negative ecosystem services, meaning they are not conducive to our health or our wellbeing, such as mosquitos or plants that trigger allergies. You need expert knowledge to identify the suitable organisms for the greening. What we are currently witnessing is an often-polarized debate on greenery for buildings that is viewed either as advantageous or disadvantageous. As the responsible planners and researchers, we need to paint a holistic picture. At the moment, there is a completely nonsensical argument in favor of greening buildings to reduce CO2 levels. The volume of CO2 that these few trees and climbers will absorb is of absolutely no relevance in the context of climate change. Using such an argument is greenwashing because it bears no comparison to the building’s CO2 emissions.

We must likewise consider what greening systems we are talking about. There are very robust and simple, cost-effective methods such as the classic greening of facades using climbing plants. Tree facades are another possibility. A system that looks great but requires massive care and maintenance inputs is something I would tend to term a natural ornament rather than a holistic and sustainable solution. If the greenery dies, the whole thing looks awful. For that reason, what we need are holistic solutions and a different form of communicating on the subject; in ad images the green systems usually look top-notch, shown in the middle of summer; they overlook the other three seasons in the northern hemisphere. No natural aesthetic is perfect, and we cannot expect to achieve that kind of desired perfection. A plaster façade behind a tree façade is not going to be a radiant white, and trees shed their leaves in autumn. Our designs need to reflect that reality, and we must communicate this – that simply happens far too infrequently, in my opinion. Designs with nature are presented far too dazzlingly, as if it were product advertising, renderings that promise a situation that cannot be achieved, or, if it can, then only at great expense. We always say we need integrated designs. To that end, we as Baubotaniker should be involved from the outset in order to systematically factor nature into the thinking. Simply making a design “greener” just before the plans are ready to go isn’t going to get us anywhere.

You founded the research field of Baubotanik at the University of Stuttgart and now champion it in your teaching and research at TU München. What do you most want to teach the next generation of architects and construction engineers?

Prof. Ferdinand Ludwig: At the moment, I largely teach landscape architects but also, quite consciously, architects, as we believe we have to make up lost ground here. Landscape architects have understood a lot of things that the architects have not yet got to, such as thinking in longer periods of time, incorporating development processes and maintenance concepts, and understanding topics such as water management. And that is what we want to convey to our architecture students, too, namely what is quite standard in landscape architecture; that we need a new systemic understanding of a building as an integral part of an ecosystem. There’s an incredible opportunity here, because we can then contribute locally to improving the ecosystem. And of course, we must do our homework here with regard to resources, energy, etc. We try and give the students a positive outlook and approach.

You head up the architectural practice OLA Office for Living Architecture together with Daniel Schönle and Jakob Rauscher. What are you working on at the moment?

Prof. Ferdinand Ludwig: At present, among other things we’re working on a project for Munich, for a forecourt of the Thomas Morus Church. It’s a Baubotanik grove of trees, a roof made of tree canopies using hornbeams. These trees have multiple trunks that can in part be interconnected, and into these grow benches, on which you can then sit to enjoy the microclimate of the trees. The grove of trees is also a spatial filter for the design of the plaza. It’s an integral part of the design. Water management plays a role here, as we use the surface water from the sealed surface to irrigate the trees.

”The questions we ask ourselves, such as the course climate change will take, should essentially be raised for each and every architectural proposition. For example, what type of tree fits the particular situation, how water supplies will function as resources dwindle, etc., because even classic structures need to function many decades down the line. We construct buildings to fit the respective present climate, but it may be completely different in 40 years’ time.“

How might the urban architecture of tomorrow, one that includes trees in its thinking, affect us humans?

Prof. Ferdinand Ludwig: The vision of Baubotanik is that the house becomes the tree. If all houses in a street become trees, then the street becomes an inhabitable forest. If you then imagine such a situation where the branches grow out of the houses, as it were, then we’re getting somewhere, namely to the place where you could start to feel as if you were living in a baubotanischen city.

Tip: Prof. Ferdinand Ludwig is currently busy preparing the exhibition on “Trees Time Architecture” that will open on March 12, 2025, at the TUM Architecture Museum. The exhibition will explore the topic of trees and architecture in three large galleries and in outdoor installations.

Wachsende Architektur

Einführung in die Baubotanik

Ferdinand Ludwig, Daniel Schönle

2023

Pages: 224

Language: German

ISBN: 978-3-0356-0331-6