Obituary

Danced with concrete

It was in 1984 on his 55th birthday that after an amazing ten years in which his career truly took off, Frank Gehry first pronounced that he was satisfied with his work. He had felt depressed for many years, as a young man had driven trucks in the daytime and attended college in the evenings, had initially been uncertain about what profession might interest him, and then not been particularly successful as a young architect. Gehry was born on February 28, 1929, in Toronto as Frank Owen Goldberg, the son of Jews of Polish descent. In the mid-1940s, the family moved to Los Angeles in search of a better life. Gehry studied at the University of Southern California U.S.C, first enrolling for Design and then Architecture, till 1954. The fact that in 1954 the family changed its name on account of the antisemitic environment is something that Gehry, who later lived his Jewishness with pride, often regretted.

After a year in Paris in 1962, he opened his own architectural practice in Los Angeles. It was through a psychiatrist that the architect got to know other artists such as Ed Moses, Jasper Johns, Elsworth Kelly and Robert Rauschenberg. Not to mention Richard Serra, Claes Oldenburg, and Andy Warhol, who along with writers and actors numbered among the large circle of friends of the forever friendly and amenable architect. The influential New York architect and curator Philip Johnson became Gehry’s mentor and patron. It was also Johnson who in 1988 raised Gehry’s profile by including him in the legendary New York MoMA exhibition "Deconstructivist Architecture“ and placing him alongside renowned colleagues such as Daniel Libeskind, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Eisenman, Zaha Hadid, Coop Himmelb(l)au and Bernard Tschumi – and all on account of a single building. The conversion of his own suburban house in Santa Monica using raw materials like corrugated iron, chicken-wire, and plywood to create slanting, splintering, tilting forms emerged as one of the incunables of the caroming architecture of deconstructivism. At a later date, in the 1980s he created numerous typically Californian buildings that were not as raw or angry as his own house.

As a West Coaster, Gehry did not become absorbed in solving social problems and avoided the virulent architectural discussion of the day surrounding type and meaning. He left architectural philosophy to colleagues like Peter Eisenman even though he was more than capable of joining in the debate. Whether it was a university institute in Connecticut, a library in Hollywood, or a villa in California or in Minnesota at that time he built collages of colorful cubes to counter the rampant tedium of sparse everyday architecture. He wanted his buildings to be unconventional, awkward, and startling; he did not worry about smooth functions or structural perfection. Instead, Gehry was interested in expressing complexity and contradictoriness using artistic, intuitive methods. Rarely in the 20th century has architecture been regarded so resolutely as art.

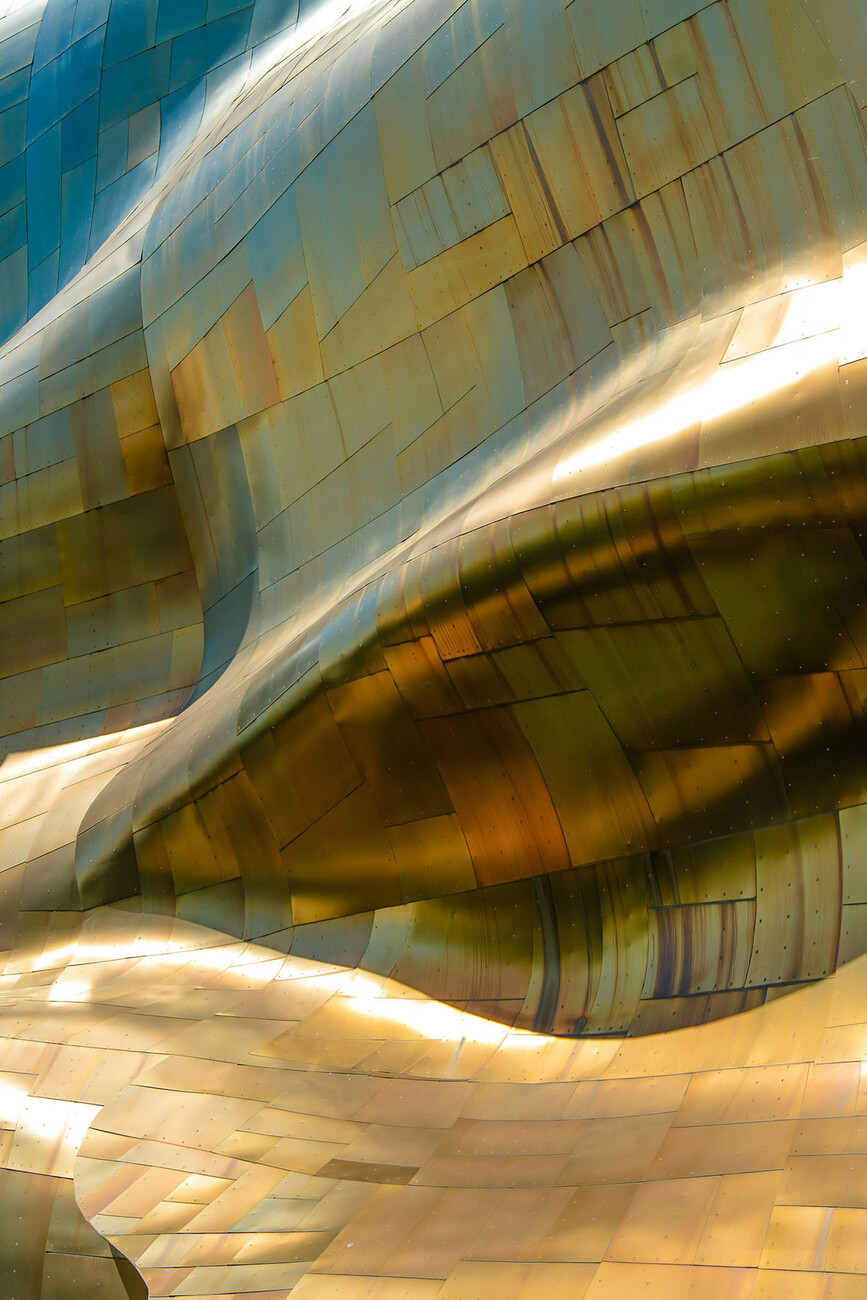

His global success came when he turned to spectacular, wild compositions of curving, folded, corrugated structures notably with the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (1991-97) which marked the climax of his oeuvre. The Guggenheim became such a huge success that the entire city profited from it and was given an enormous economic boost. This came to be known as the “Bilbao effect“; pushing urban development by realizing an outstanding piece of architecture. However, he seemed to have exhausted his design repertoire with this building. Those that followed, such as the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles (2003) were mere flights of self-referential fancy, the Biodiversidad Museum in Panama, not unlike a colorful pile of scrap metal when viewed from a distance, a feverish, mannerist apocalyptic fantasy of deconstructivism. He did, however, cause a sensation one more time with his signature architecture in the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris (2014), even if the whimsical bouquet of glass umbrellas and bowl shapes seems totally unsuitable for its actual purpose, namely exhibiting artworks. However, the "Bilbao effect" which the developer had counted on, does indeed work and the building pulls large crowds of visitors.

Over the years Gehry developed his own visual language for office buildings which he achieved by squeezing cubes or rounding them out for form cylinders, cladding them in contrasting materials like bricks, sheet titanium and plaster. Examples of this approach can be seen in the "Dancing House" (Ginger and Fred) in Prague or in his projects in Germany, the Neuer Zollhof in Düsseldorf (1999), the Gehry Tower in Hannover (2001) or Museum MARTa in Herford (2005). Only once did Frank O. Gehry give his commentators something to puzzle over: that was when he built the DZ Bank (formerly DG Bank) building in Berlin. Suddenly, on Pariser Platz next to Brandenburg Gate there was a heavy, stone box that did not exude anything of Gehry’s carefreeness and nonchalant free spirit. The solid outer wall with deeply incised, stereometric window openings has been read as an ironic commentary by Gehry given their grotesque caricature of Berlin’s design guidelines ("the stony Berlin"). However, what you see inside is Gehry at his purest, a squashed room that seems suspended in the atrium, a room some see as being shaped like a horse’s head. And he also remained true to himself on the South facade, where he might have used the prescribed stone façade, but with vibrant walls and dancing casement windows, as previously featured in the New Zollhof, Düsseldorf.

Gehry’s latest works could only be realized by a highly specialized team using advanced computer technology. However, a glance into the creative chaos that was his studio reveals the passionate artist, who hammers, kneads, works, and arranges the structures by hand until he feels he can live with the result – but without ever being completely satisfied. Only then did he hand over the result in the guise of ingenious sketches and unfinished models to his colleagues and the structural engineers, who then would throw up their hands in despair during the construction and execution planning phase – as was once the case with Hans Scharoun, whose complex spatial creations often remained a mystery to the staff assigned to realize them.

Frank Owen Gehry passed away on December 5, 2025, at the age of 96 in Santa Monica, California.