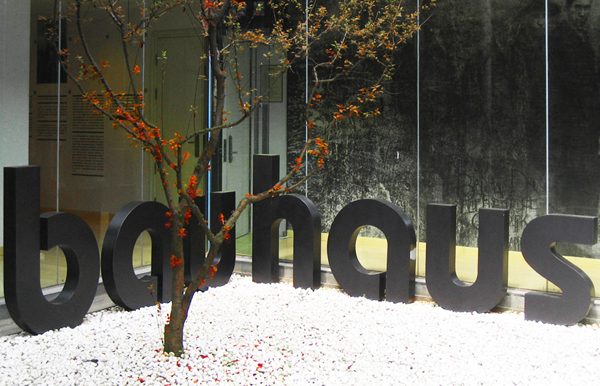

The sale of the Bröhan Collection to the Chinese Academy of Art (CAA) in Hangzhou two years ago was a cause of much astonishment among the cognoscenti. It was a quite remarkable occurrence. There’s the quality and sheer size of the collection (comprising 7,010 items), its importance for German design history, and not least the transposition to a quite different culture. All in all, hardly an everyday transaction. As present, a selection of some 140 exhibits is on public display in a provisional setting. Egon Chemaitis, designer and until 2011 Professor for Design Foundations at Berlin’s University of Arts, spoke to Song Jianming in Hangzhou who took part in the purchase negotiations. Song Jianming studied among other places in Paris and currently teaches “Color Theory in Architecture and Cities” while conducting research on the same topic at the Chinese Academy of Art (CAA). One of Song’s most recent projects – in addition to work as an advisor to some 50 Chinese cities – was the color design for the Chinese pavilion at Shanghai Expo 2010. As CCA’s Vice-President he was involved in the purchase of the Bröhan Collection from the very outset. Egon Chemaitis: How did the idea arise at CAA to acquire the Bröhan Collection? Or were you simply offered the collection? Song Jianming: Importing the collection to China was really a big deal. The reason being that everyone here involved in design was very interested in the collection. This is true of both the younger and the older designers and of everyone interested in design. We were pleasantly surprised when we heard that the collection was up for sale, and got to work straight away. To be honest, as an art university we alone would not have been able to acquire and take on a collection of this quality and scale. By contrast, the Hangzhou City Council has the requisite financial resources, but would not be able to care for and present such a collection. But it was very confident that our university could. In our dealings with the City Council, we continually stressed Bauhaus’ great importance in the history of design both in China and the rest of the world. Whereupon the government said: if you think it is so important then we should go for it. After all, you have been collaborating with Germany for years now (NB: Song refers here to the Sino-German Art Academy CDK), and President Xu Jian studied in Germany, you have lots of contacts to German institutions and for some time now. So you guys are in a good position to do it, so go for it. Which brings us to the substantive issues. We Chinese designers know a lot about Bauhaus, about German design history and the various museums there. Yet this always remains a rather superficial encounter. What we often don’t know is what is behind things. We only know that there are beautiful images, interesting treatises and impressive objects, but we don’t really get to the bottom of things and get caught in appearances. But we want to dig deeper! All the treatises, all the documentation has to be translated, which actually means really worked through the material. And we learn in the process. Yet our knowledge remains fragmentary. Even though we are able tow hold an object in our own hands, study it closely with our own eyes and really understand it. That is to say, the collection makes Bauhaus into something concrete. It allows you to gain insights into things, into Bauhaus, by taking a look for yourself, from your own research perspective. The section of the collection that is currently open to the public features pieces that were made well before or indeed well after Bauhaus. How much “Bauhaus” does the collection actually contain? Jianming: You’re right; there aren’t that many actual “Bauhaus” pieces in the collection. However, we’re not only interested in Bauhaus, our interest lies in the cultural and design history. We’re interested in the entire chain. These things play a role in our lives, the related technology and production methods are bound up in both our lives and our history. We want and indeed have to understand what happened during that period. These things are real – like our lives. That is the social perspective of Bauhaus, or rather of the modern interpretation of design. An educational program of sorts. Few Bauhaus designs actually became mass-produced articles. Jianming: Yes, that’s true but the influence that this particular interpretation of design had on mass production is not to be underestimated. When I think about the founding of the Bauhaus and the present-day situation in China in their respective historical contexts, Ulm School of Design springs to mind as a more logical paradigm. Max Bill’s dictum on range, “from a spoon to a city”, mass production and mass communications as central perspectives on modern design as well as the moral impetus provided by the Ulm School – would the Ulm School not offer more conceptual or methodical patterns for the tasks faced by designers in China Jianming: Perhaps for you. For you, Bauhaus is Bauhaus and Ulm School of Design is Ulm School of Design. But for us the whole package, this entire stretch of design history is of interest. I’m no Bauhaus expert but these objects have taught me a lot about German philosophy and aesthetics, and how systematic the German approach is to this part of civilization, to life in general. That is what interests me. Others are only interested in the design itself and find this aspect of the research particularly interesting. We take these objects as a food for thought; for us, they constitute intellectual resources. Now the objects are here and everyone is able to gain something from their own specialist perspective. As far as I could see, the collection seems to span the entire last century. From Riemerschmied and the Deutscher Werkbund, to Wagner and Hoffmann before Bauhaus; then from Aalto and Rietveld to Sapper after Bauhaus. The whistle kettle – not so Bauhaus in its style – seems to be the youngest exhibit. Jianming: Indeed, the collection spans a period of around 80 years. Philippe Starck is also in there, by the way. It really does include more than just Bauhaus pieces. The items currently on show can in essence be split into two product categories: on the one hand we have pieces for the table – porcelain or glass dinner services, silverware, vases etc. – on the other, seating furniture. Is this representative of the whole collection? Jianming: As I already said, Bauhaus isn’t the only focus of our interest. Our aim is to study and understand the entire development chain of Western – in this case German – design history. But in that case the three-dimensional lettering piece (in Bauhaus font) is rather misleading, isn’t it? Jianming: Bauhaus is very well-known here; everyone is familiar with the name. Plans foresee the collection being housed in its very own museum. The building designed by Alvarò Suiza is still on the drawing board. What will the museum be called and when is it due to open its doors? Jianming: It will be called the Museum of Modern Western Design of the China Academy of Art and is set to open in 2015. Will the museum house this collection alone or are there plans to extend the collection in the future? Jianming: We want to carry on with our work: We will look to the skies and hope that one day more manna falls from heaven. The CAA has had to incur the follow-up costs for the analysis and maintenance of the collection, for its conservation and working up – including some extremely elaborate and complex translation work. Jianming: It required a huge expenditure; that is without doubt. We are putting a great deal of effort into it, we really can’t just wait for manna from heaven, we have to work for ourselves. But will the city of Hangzhou provide you with support again? Jianming: The economic situation is no longer so good in China, we can’t keep nagging the City Council to give us more money. We have to make something for ourselves. Speaking of money. In a recent Master’s thesis, I read that the purchase of the collection is said to have cost 55 million Euros. Had the student done her research? Jianming: Well, if you’re asking me if this figure is accurate, my answer would be: I can’t say anything more on the matter. Our partners should know that we are trustworthy. Of course that is to be respected. I was just wondering where this information has come from and how it could crop up in a Master’s thesis. Jianming: There are lots of different figures doing the rounds in China at the moment. But no one knows anything specific. I am the only one who does, and no matter who asks – be they Chinese or German journalists or colleagues, or those of any other nationality for that matter – I won’t say a thing. A year and a half ago, the CAA held a Bauhaus congress – “Bauhaus in China” – with participants from across the globe. Will such events be taking place in the future? Jianming: We will be holding a research symposium each year. This year the focus will be on “New Bauhaus” and I will travel to Chicago for it. Our president wants us to explore this field too. Bauhaus has always been a hot topic in China, even when I was studying back at the beginning of the 1980s. The Museum Director, Han Jian, for example is at the helm of the research work on Bauhaus. So you’re not only building a museum but a research lab for modern design history in the West? Jianming: In China it is a kind of research institute, and indeed we would like to take on Master’s graduates and students working toward their doctorate. The spatial and technical requisites for this have been included in the museum’s design. We are more than just collectors! Ordinary people are astounded that we would buy and preserve such ugly things, even more so that we revere them. They don’t understand why we do it. The Chinese want to marvel at fine, classical items. An historical parallel to the beginnings of Bauhaus and the Ulm School when one considers the uproar surrounding the flat roof and the SK 4. And, when you look at it like that, perhaps this is a confirmation of your work. Jianming: Here in China, collecting is associated with antiques that represent certain dynastic epochs or rulers, with historical costumes, jewelry, decorative items and such things. But not with used, at times broken, unadorned or simple things. Why would you want to collect them? (Interpreter: Xiao Yi Liu-Cuk, Graduate in Engineering and Architecture)

It bears stating here that in China there are countless universities, but the CAA is the only one with such close links to German institutions; it has a strong reputation in this regard. Yet the fact that the City council supported CAA in this matter and with so much trust, was for us like manna from heaven. I remember all too well the moment when I and President Xu visited the City Council and the Lord Mayor said to us: I’m giving you the collection. President Xu looked at me in disbelief and asked me in our home dialect whether he could trust his ears.