In the in-between

Elisabeth Bohnet: Your art can be described as a place where nature and culture come together. What does "landscape" mean to you?

Olaf Holzapfel: In terms of art I consider landscape to be a way of correlating the different factors that determine the kind of work you could realize there. That is also what my work is all about: I assume that sizes, certain aesthetics and materials, repetitions and abstractions already exist in the landscape. The landscape itself provides guidelines for how something is built as do the cultures with their traditions. Things are put together as is the case with human language. I then delve deeper because generally there’s a reason why certain things can be combined while others can’t. The underlying causes for this lie in the materials themselves which occur in the landscape. Taking it a step further it is also about the contradiction in which we find ourselves: On the one hand there is theory and the world of language and on the other a material world without language. I would like to resolve this contradiction.

You focus a lot on traditional techniques. What do you find so fascinating about artisanship?

Olaf Holzapfel: There’s this saying: "The hand provides the shortest route to the brain." The work that I produce using my hands originates straight from my brain. So many different senses and experiences lie in our hands that they have a direct influence on our thinking. This explains the connection that exists between artisanship and the material world. In this sense, machines are advanced manual techniques. However, I’m more interested in a simpler route to the material world as precisely in our era it holds the key to many things in the future.

So where in your works, say in your half-timbered objects, does the handcrafted product become art?

Olaf Holzapfel: Through the context. After all, it is an assertion to claim that something is art. Art has completely different criteria such as a certain quality in its realization or participation in a debate. I also exhibit artisanship, the work itself. Often these activities are very mundane, ancient, or common but when placed in a museum context they become a subject for reflection and an object of this art world. This makes it possible for the observer to see such items in a different light. To not only think about them theoretically but also to consider the sense of such crafts or objects. Normally, one might perhaps argue that artisanship is not efficient and takes too long; it would be better to use machines to make the chair. However, in the art domain I am prepared to reconsider the item. In Pop art ordinary, everyday objects were used to show that they reflect our lives. A can of Campbell soup has a symbolical value as it enables us to reflect on our culture and consider what the object of art is. It’s similar with artisanship, except that the dimension is totally different because these things span completely different temporal dimensions as do lichens and ferns. What is current, what is past and what surrounds us permanently? Landscape surrounds us constantly but perhaps crafts or other things are also there permanently simply because we will always make them and can always make them. And the scope that this creates generates freedom and unleashes creativity.

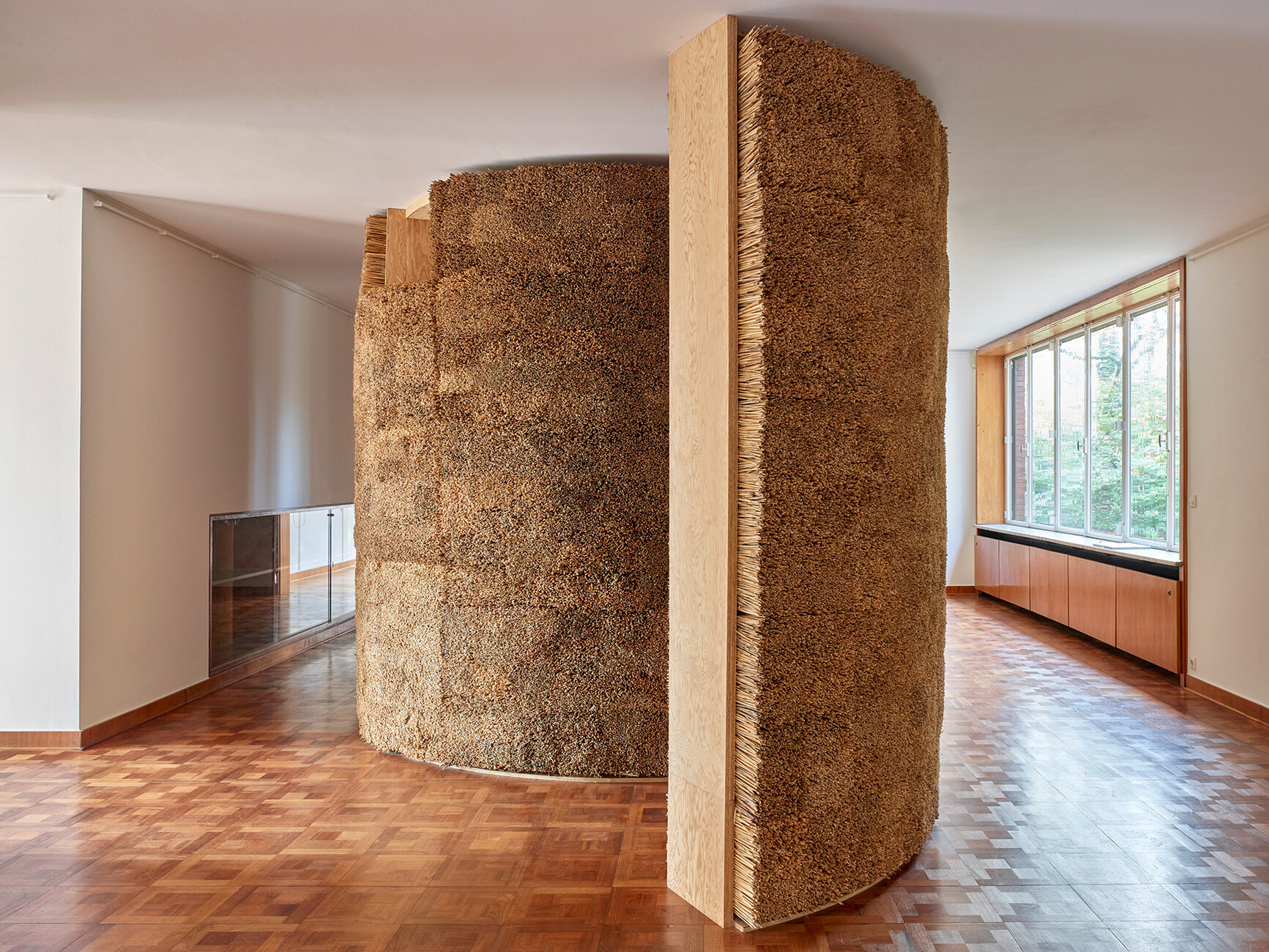

One of your works that is currently on display in Dessau showcases the wall as a participatory exhibition.

Olaf Holzapfel: We built a wall in the German Federal Environment Agency. I produced the design and part of the main structure, after which many other players got involved and worked collaboratively. It’s also about the presentation, the realization, the actual building. It’s paradoxical that in our world full of rules who is ultimately responsible for your own house is not clearly resolved. Years ago, it was usual for people to look after their own houses and they knew: "A beam needs to be removed there." They felt responsible and consequently participated in the architecture because they became builders themselves and didn’t have everything made by the architects. Most houses in rural areas were built by the farmers themselves in collaboration with experts and carpenters, but the clients were involved in the building work. That’s what constitutes the beauty of these buildings for me. And that’s why we feel good in them, look after them, place them on heritage preservation lists. That does not only happen because they are old but also because they are representative of our culture. This is where we come full circle back to art.

The turn of the century saw a move away from historicism. Adolf Loos’ essay on "Ornament and Crime" was misunderstood and decorative building was abandoned. Loos himself was much more concerned with what he saw as the false use of decoration, but he was not a purist. Nevertheless, most people I know today are keen to live in Berlin’s Charlottenburg, Wilmersdorf or Prenzlauer Berg districts. In other words, they prefer these old houses that are historicizing. Historicism was actually a modern idea. Since so much was being built back then people thought about how to combine the new with the feeling that we are not completely removed from time but are connected with our surroundings and our past. That is why these historic formula were developed, not to generate architecture solely for investors but to build architecture people would be able to identify with and live with and experience beauty where the aesthetic plays a role. Take Jakob Ignaz Hittorff, who built the Gare du Nord in Paris or the Bourse de commerce, which is now home to the Pinault collection. He was a very modern architect, but he also integrated these historical formulas. Visually the Gare du Nord is in keeping with the city, while inside it is a highly modern building, built of steel and constructed on site using the latest technology. What we see is mediation between these different interests of the public – which brings us back to participation and identification. In other words, many things that are very important again today.

Yet you see very little of that in contemporary architecture, don’t you agree?

Olaf Holzapfel: We are starting to see it. Take Chinese architect Wang Shu, who won the Pritzker Prize in 2012 for his idea of combining recycled building materials with more traditional forms or the Danish Wadden Sea Center by the Dorte Mandrup office that has a spectacular thatched roof and facades. The enormous financial pressure in architecture prevents more thought being given to such connections between tradition and contemporary architecture.

The idea behind the "Wall" exhibition in Dessau is that the four walls we live in are our closest neighbors. This assumption makes us think differently about this structural element, to consider that walls not only serve as a means of division. For the exhibition "Anders Wohnen" in Kunstmuseum Krefeld I lived in Mies van der Rohe’s villa for a while. I was very aware of how he linked the inside with the outside and simultaneously how he addressed the garden, in some cases had the garden created first. For the neighboring Haus Lange and Haus Esters in Krefeld he began by having 700 truckloads of soil piled up to produce a topography of sorts that he then built on. The landscape is a part of the houses, not only visible through all the glass but is also a direct reference point: Like a negative or positive mass around the buildings. During modernism you already have a very fluid transition between inside and outside and today we operate in another kind of inside and outside: namely in the digital and analog world. If the digital 3D-world continues to expand then people will sit inside and imagine they are in a rainforest. I asked myself, what do we need, what would be a good response to such topics? In the "Rückgabe Reimbursement Cells – Cellulare Dialektik" we have integrated a cell that you can retreat into.

Following you being awarded the Zurich Art Price, the exhibition "Der Mantel" (The Overcoat) is now being shown in Haus Konstruktiv. In a work created for this exhibition that goes by the same name you exploit the association of an enveloping garment.

Olaf Holzapfel: The "Wall" project was one of the things that gave rise to the Overcoat sculpture. I’m interested in things that are in-between and that you participate in. Organic things, for example, like wood or plant fibers that are transient. Yet as items of furniture they can last for 600 years – if we want them to stay around. We can decide to keep things, but we can also simply let them go. And this being in-between is also a property of organic materials. A coat is also in-between: it surrounds us, but at the same time it’s part of the outside world. It is a transition zone that simultaneously separates, warms and connects. At the exhibitions I experienced again and again that the things which move people are precisely the things made of organic materials. We seem to recognize ourselves in them – as we are ourselves organic, after all. And we recognize that we are both impermanent. We are also in transition, always on the move. That’s perhaps why the coat expresses something metaphorical.

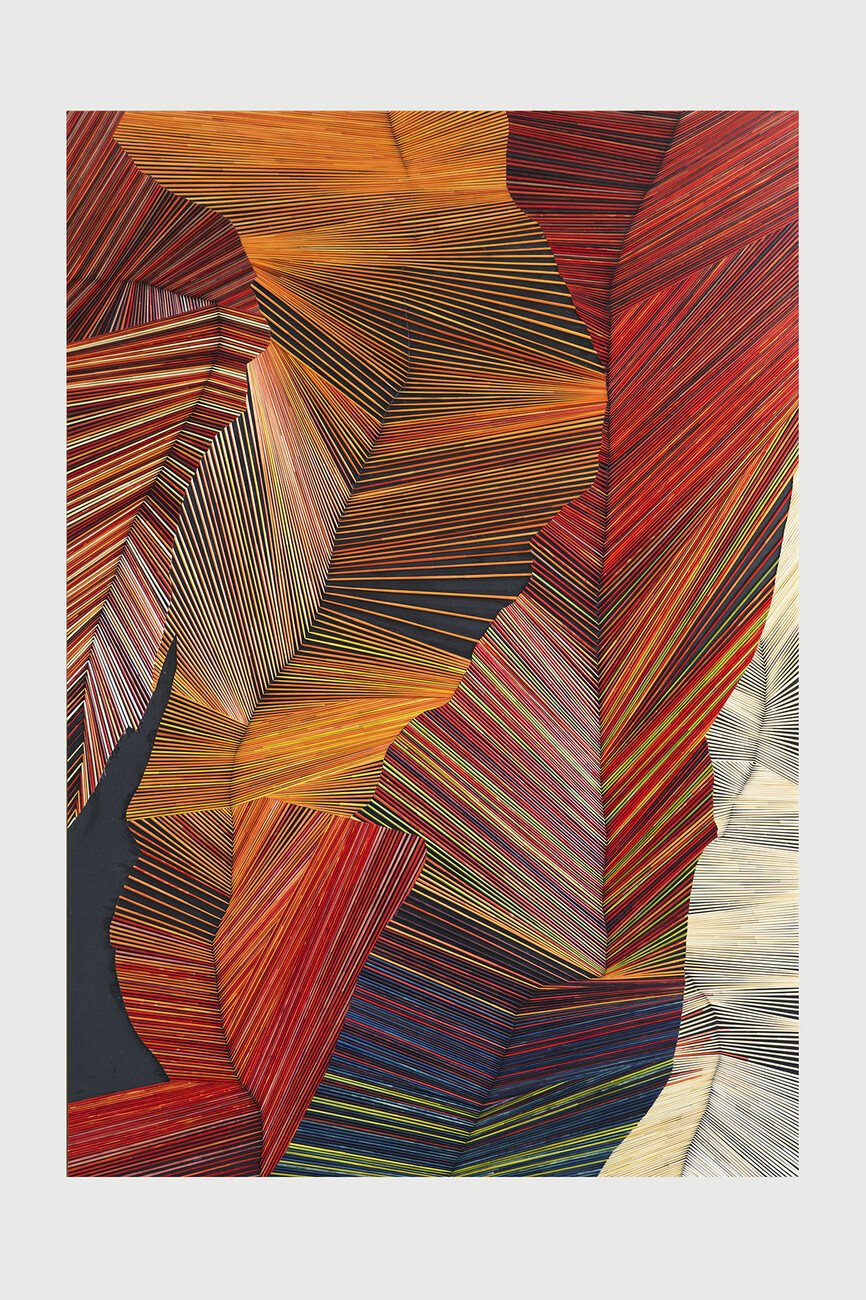

For several years you have been making straw pictures by naturally dyeing the straw and arranging it in geometrical patterns on a background. That takes you away from spatial art and in the direction of relief. What makes straw such a fascinating material for you?

Olaf Holzapfel: Straw is so mundane that we tend not to perceive it as a material for artworks. You find little straw in art except in Anselm Kiefer’s art where it’s combined with dung or soil. And yet you find a great many straw objects in the area of crafts, and they occur worldwide. It’s a versatile material that often has a symbolic meaning for people, representing say light or recurring numbers.

And indeed straw features in almost every depiction of Christ’s birth, albeit only painted, not as an actual material.

Olaf Holzapfel: Yes, that’s where the symbolism of wealth and warmth comes from. Or in Brueghel as wealth in a land of milk and honey. It’s fascinating how many doors open, once you start to explore the topic.

You once said, "Art is a symbolic discipline, a bit like politics." What do you mean by that?

Olaf Holzapfel: In politics it’s also about beliefs and a dialogue involving various viewpoints. Politics should argue, not defame – and so should art. In the European art scene we are always putting forward different beliefs and artefacts to make sure we know where we stand and where we want to go. So art also has a speculative momentum. And is sometimes criticized for that. However, I think that’s ridiculous; it’s good that art is speculative and prepared to take risks. We have always profited from that in Europe. We always took risks with our ideas. And that’s why art must be free, as stated in the German constitution. If art can’t be free, if it can’t be totally speculative, it dies. At least our kind of art does. After all, we have few other places where we can negotiate things symbolically. Nobody is directly harmed by a speculative action. And if someone sees art as doing harm then they are always mistaken. First of all, the art itself has a different goal. It seeks liberty, to reflect about certain things and to be spiritual because we need that. Architecture is located somewhere between politics and art. And though it would actually prefer to be one of the fine arts it is much more dependent on the politics of the day. As the "original form of art", architecture must generate a practical value, something the visual arts don’t have and perhaps should not. And later when we bring everyday objects into the museum and determine that they have an artistic value, then we are assessing their symbolic value. And has something like the Campbell soup can or an iconic Bauhaus chair gained acceptance? Then it has become art because the form, the aesthetic component has taken on such an importance that we appreciate and buy it primarily because it represents something that has asserted itself and makes important statements about our everyday lives.