Is it becoming extinct? Is it flourishing? The shelf is standing at a crossroads. A glance back at historical predecessors and the latest examples casts light on a piece of furniture that has not only enriched the intellectual and cultural history of the past decades, but also allows the oft-debated principles of order and openness, of rules and the breaking of taboos within living space, to come to light.

The debate on the standardization of types of industrial products began in the German Werkbund in 1914. Hermann Muthesius (1861-1927) argued that "not even domestic demand is covered by ad hoc objects artists design". Henry van de Velde (1863-1957) countered thus: "Some of us have been searching for the past 20 years for the forms and embellishments to perfectly complement our epoch. However, the idea of wanting to impose on others these forms and embellishments that we have been seeking or have found now as types has not occurred to any one of us." The debate ultimately revolved around individuality versus seriality; and is continued in design to this day. While the question remains unanswered, Muthesuis seems to hold the stronger position.

Around 1900 a new kind of furniture was required for the ever-increasing number of rental apartments – less lavish, but yet still functional. The shelf was released from the wall and niche. It was no longer workshops that matched furnishings according to an architect's plan and in line with a building's individual type and its oriels, vantage points and gathering places. They were replaced by a specialized industrial sector, one which concentrated on the manufacture of free-standing cabinets.

Even before the Werkbund debate, many architects sought to specialize. Bruno Paul (1874-1968), for instance, designed a complete apartment interior, which he called "type furniture" ("Typenmöbel") and which was manufactured by the Vereinigte Werkstätten für Kunst im Handwerk in Munich. Architecture historian Sonja Günther quotes from the advertising brochure for the furniture which premiered in 1908: "It does not flaunt itself with superfluous embellishment, thereby sparing its owner disappointment. The solidity of its exterior form is matched only by that of its workmanship. It can easily withstand the damage otherwise inflicted by frequent transportation. The pieces are also compact enough to be positioned even in awkward spaces." In short: modern furniture – the modern shelf – was born.

In a traveling exhibition on Ikea, Bruno Paul's bookshelf was displayed as a precursor to "Billy". However, there is more than just decades of furnishing history between the two. Indeed, styles and materials, as well as the modes of designing, manufacturing and operating have also radically changed over the past hundred years. It was not the arrival of the Internet that first enabled furniture production to be internationally organized in terms of the division of labor. Images of "Billy" and Bruno Paul's "type furniture" may present formal similarities, yet at the same time they also draw attention to the transformation of the design industry.

Today it is precisely the variety and ability to plan that pose a challenge for shelving manufacturers and suppliers. In order to be able to respond quickly to customers' wishes, they require their own production facility – or at least a well-oiled system of planning, commission and delivery. The highly simple shelving unit "Billy", designed by Gillis Lundgren (born 1929), the fourth person to be employed by Ikea, has sold around 42 million units worldwide since its market launch in 1979. "Billy" is becoming ever more popular. This would be unthinkable without the involvement of the customer, who must take responsibility for transporting the unit to their own home and constructing it themselves.

Urban planners

Le Corbusier (1887-1965) specifically designed his living machine, the Unité d'Habitation, to resemble a shelf. In order to clarify its construction process, model photos show how the building's maisonette apartments, each positioned around central access corridors, were slid into the load-bearing structure of reinforced concrete. Cassina has now launched as the "LC 16" a re-edition of the furnishings, combinations of tables and shelves, which Le Corbusier conceived for the Unité in Nantes-Rezé.

In 1961, a steel construction system marked the beginning of a collaboration between architect Fritz Haller and the metal works USM located in Münsingen in Switzerland. USM used the system of load-bearing structures and façade elements for its own production building, additionally offering it in three formats – "Mini", "Midi" and "Maxi" – for factory buildings and offices. Later on, architect and company followed similar principles (a limited repertoire of construction components and intelligently designed joints) to design a furniture system that is still in demand today in law firms, doctors' surgeries and living environments due to its purist, yet at the same time glamorous character. However, it is a lesser-known fact that between 1968 and 1980, Haller developed his ideas on building and construction further and came up with the concept of the "total city". This encompassed structured settlement concepts and transportation systems in minute detail, ranging from the smallest unit "E1" (a structure for 3,300 inhabitants), right up to a "space colony" in space close to Earth.

A connection between the shelf and urban structures can also be found in the creations of Andrea Branzi (born 1938). Most recently the exhibition "Megastructure Reloaded", held in Berlin in 2008, was a reminder of the fevered dreams and visions of the architects of the 1970s, who planned load-bearing structures that would span the world in order to build sports grounds, residential towers, transport systems and amusement parks within them. Since taking part in the dystopia "No-Stop-City" by Archizoom in 1970, Branzi has become more and more preoccupied both with how nature forces its way into the house, and equally with buildings and cities that dissolve into the countryside. As the link between technology and form is weakening, in his 1994 countryside utopia "Agronica", developed at the Domus Academy for Philips, Branzi calls for a "lightly-urbanized" space. There, cows graze beneath roofs that look as though they were built by Richard Neutra. Giant shelves are scattered across the cultivated countryside: the remaining components of urban structure.

Exhibition organizers

Many architects and designers of new shelves and modular shelving systems did not have the cityscape in mind when conceiving their ideas, nor houses as domestic shelves or new forms of settlement for the universe. Rather, they sought practical classification structures initially for exhibitions. One of the pioneers in this field is Franco Albini. During the 1930s he built open, transparent metal structures which he later combined with steel-cable anchors. His 1936 exhibition at the sixth Triennale, which showcased ancient gold jewelry, can be considered a milestone in exhibition design. The space was structured by delicate, elegant ladder structures with mounted glass cases illuminated from above. He planned similar structured spaces for private living areas. In 1941 he created new rooms for the Brera Art Gallery in Milan and installed a vertically-oriented structure in the historical rooms. The confrontation between historical architecture, exhibit and an ultra-modern form of presentation runs through all Albini's works. There are strong links between his outfitting of the Olivetti store in Paris in 1958 and the system of shelves he developed shortly beforehand named "Library LB7", now being produced once more by Cassina. This system's shelves can be braced between wall and floor, thereby allowing them to be placed freely in the space while at the same time remaining accessible from both sides.

"Veliero", which Albini built for himself in 1938, plays a special role. One similarity with later designs is the tapered and multiplexed support. In 1941, the magazine Domus placed "Veliero" at the center of a multiple-page report on Albini's apartment in Milan, documenting the anchoring, components and assembly in great detail. "Veliero" is reminiscent of the hanging models of Antoni Gaudí or Frei Otto, with which they tested the construction principles of their buildings. Cassina has taken great pains to reconstruct the design and will introduce it this year in Milan as a new (small) series product.

Interior designers

In the post-war period, when few materials and living spaces were available, architects and designers employed the shelf as a universal piece of furniture, often using it themselves to begin with owing to their own lack of furniture. In 1949 Nisse Strinning (1917-2006) used ladders made of round steel, which were attached to the walls, as the material for his "String System", which can be combined with shelf boards and boxes. It contributed swiftly to the spread of Scandinavian design throughout Europe. Dieter Rams (born 1932), living in a cramped loft apartment, had been working at Braun for two years when he designed his mounting system "571/72" for Vitsoe & Zapf. Four perforated aluminum strips were screwed at their ends to veneered wood core plywood panels, their sides linked laterally with special aluminum components. Drawers, boxes and doors were also part of the system, which Rams and Vitsoe developed over decades before it was discontinued in 1995. Today the system "606" is far more famous, currently sold by SDR+ and the now British firm Vitsoe. Like Albini's system, it can be mounted both in the room or on the wall. De Padova offers a version made entirely from aluminum.

Many trailblazing furniture systems of the 1960s have long since been forgotten. The construction-set furniture "M 125" by Hans Gugelot (1920-1965), the "In-Wand" by Herbert Hirche (1910-2002) and the "Comprehensive Storage System" by George Nelson (1908-1986) are some of the classic shelves that have already slipped from public memory. Also almost forgotten today is "Metrix" by Peter Maly (born 1936), an important contribution to German post-modernism, which came with a characteristic frame that protruded into the room. Since then Maly has been developing lighter and more open systems, such as "Lines" for Ligne Roset or "Duo Plus" for Interlübke.

Love of order

The recent history of the shelf begins – of all things – with the anarchistic New German Design of the 1980s. Wherever you look, there are shelves. One such example is the "Verspanntes Regal" by Wolfgang Laubersheimer (born 1955). It is an icon, calling everything into question: such as the appropriate choice of material, for example. Steel is far too heavy for shelves. Or perhaps the size and the tension. Can the thing not simply stand in its place, inconspicuous and upright? Certainly not! Or how about "FNP" by Axel Kufus (born 1958). Where did the product's unusual name come from? FNP is the abbreviation of the German Flächennutzungsplan, meaning "land utilization plan". After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Berlin was in need of a new layout, one which would decide the location of residential and commercial, transport and recreational areas. Only how should the planning process for the entire city be organized? "FNP", the shelf made of MDF (Medium Density Fiberboard) and braced with an aluminum runner, was not merely an ideal solution for city planners. Axel Kufus was then still building the first examples himself and faxing a planning guide to interested individuals, but later "FNP" was to become one of Nils Holger Moormann's most important products. He fittingly said of "FNP": "I can accommodate an optimum number of books at a reasonable price." There was also the "Bibliothek" by Reinhard Müller and Meyer-Voggenreiter – an accessible casing, almost worthy of St. Jerome. One advert advises that it is made from "steel, leather, upholstery and carpet". Depending on the design, one should pay 8,600 marks for the "Edition Pentagon", which is a steal by today's standards. The only astonishing thing is that no-one has ever seen a picture of the Pentagon's "library" with even a single book in it. Similar considerations apply to "Carlton" by Ettore Sottsass (1917-2007), admittedly not a frontrunner of New German Design. All at once the idea of the shelf had come to the forefront, rather than its usefulness as a commodity. Consequently, images of these objects began to saturate magazines and books noticeably more frequently than the product itself.

Structural weaknesses

The shelf seems to be something of a specifically German contribution to recent design history. We need think only of Konstantin Grcic's (born 1965) staging of the shelf as an "ideal house" at the imm cologne in 2003. Here, the works of Werner Aisslinger (born 1964) are exemplary. His "Endless Shelf", which he first made himself and since 1994 has been produced by Porro, is made of MDF panels and cross-shaped aluminum elements which are inserted into perfectly milled notches in the panels. He has also developed shelves for manufacturers such as Interlübke, Zeritalia, Behr and Piure, to name just a few. In 2007 he presented "Books", a system that transforms books into a building material. It uses the once popular, now cumbersome, large coffee-table books documenting travel destinations, sporting events and culinary traditions of bygone days, which have in the meantime been stacking up in basements or attics. The books as a whole create the structure, while a connecting cross-structure provides stability. The latter, however, can be dismantled without affecting the book structure.

When designing the public spaces of Hotel Michelberger in Berlin, Aisslinger transferred gabions into the interior, wire baskets filled with stones commonly used in landscaping. Instead of filling them up with natural stones, he filled them instead with books and magazines, which function as décor in the rooms, but can also be taken out, leafed through and read.

Does a shelf even need to have books on it? "Bookshelf" is a series of furniture by the group of female designers Front for Skitsch. In actual fact these pieces are cupboards. For these shelving units, which are available in various formats, have doors at the front bearing three-dimensional images of books in the trompe-l'oeil style. "Robox" by Fabio Novembre (born 1966) is like a friendly autobot, a robot from the movie series "Transformers", which was supported by the US military. On his blog "ionoi" the designer compares the humanoid shelving unit with "Ginza", a comparably small shelving object created by Masanori Umeda for Memphis in 1982.

Perhaps in the end it is not the contents that the shelf loses, but rather its pre-stabilized orderliness, its incredibly obvious structure, which has been under threat for a long time and is falling apart like all eternal order. With "Es" (Moormann), Grcic called into question the principle of the upright, as-rectangular-as-possible unit. Nonetheless, his parallelogram of planes and rods always kept its balance. This is completely different to what Karlsruhe-based designer Tom Pawlofsky (born 1976) has done. His shelf "Zinfandel", a special edition at kkaarrlls, is made of sturdy boxes and a soft, wobbly plastic grid. The more boxes are added, the more stable the object appears to become. But even then it can suddenly lean sideways, buckle abruptly, slip ridiculously. It seems that today we can no longer rely even on the shelf, the tried and tested pillar of society.

Find a comprehensive overview of shelves here:

Already published in our series on product-typologies:

› "Everything that is furniture" by Thomas Wagner

› "Do not lean back!" on stools by Nina Reetzke

› "On tranquility and comfort" on lounge chairs by Mathias Remmele

› "Foam meadow, stays fresh for longer" by Markus Frenzl

› "In Chair World" by Sandra Hofmeister

›"All the things chair can be" by Claus Richter

› "The shelf – furniture for public order" by Thomas Edelmann

› "How the armchair got its wings…" by Knuth Hornbogen

Unité d'habitation by Le Corbusier in Berlin, Foto: David Pachali

Unité d'habitation by Le Corbusier in Berlin, Foto: David Pachali

Ideal house by Konstantin Grcic, imm cologne 2003, photo Constantin Meyer, Köln

Ideal house by Konstantin Grcic, imm cologne 2003, photo Constantin Meyer, Köln

FNP by Axel Kufus for Nils Holger Moormann

FNP by Axel Kufus for Nils Holger Moormann

FNP by Axel Kufus for Nils Holger Moormann

FNP by Axel Kufus for Nils Holger Moormann

Building block system M125 by Hans Gugelot, Credit: Guus Gugelot, Hamburg

Building block system M125 by Hans Gugelot, Credit: Guus Gugelot, Hamburg

Building block system M125 by Hans Gugelot, Credit: Guus Gugelot, Hamburg

Building block system M125 by Hans Gugelot, Credit: Guus Gugelot, Hamburg

Building block system M125 by Hans Gugelot, Credit: Guus Gugelot, Hamburg

Building block system M125 by Hans Gugelot, Credit: Guus Gugelot, Hamburg

Archigram/ Peter Cook, Plug-In City 1964, Courtesy: Archigram Archives

Archigram/ Peter Cook, Plug-In City 1964, Courtesy: Archigram Archives

Plurima by Charlotte Perriand, Cassina

Plurima by Charlotte Perriand, Cassina

Infinito by Franco Albini, Cassina

Infinito by Franco Albini, Cassina

Es by Konstantin Grcic, Nils Holger Moormann

Es by Konstantin Grcic, Nils Holger Moormann

Es by Konstantin Grcic, Nils Holger Moormann

Es by Konstantin Grcic, Nils Holger Moormann

LC 16 by Le Corbusier, Cassina

LC 16 by Le Corbusier, Cassina

Billy by Ikea, Foto: Inter IKEA Systems B.V

Billy by Ikea, Foto: Inter IKEA Systems B.V

Endless Regal by Werner Aisslinger, Porro

Endless Regal by Werner Aisslinger, Porro

Endless Regal by Werner Aisslinger, Porro

Endless Regal by Werner Aisslinger, Porro

Zinfandel by Tom Pawlofsky, Foto: Philip Radowitz

Zinfandel by Tom Pawlofsky, Foto: Philip Radowitz

Zinfandel by Tom Pawlofsky, Foto: Philip Radowitz

Zinfandel by Tom Pawlofsky, Foto: Philip Radowitz

String-System by Nisse Strinning

String-System by Nisse Strinning

String-System by Nisse Strinning

String-System by Nisse Strinning

Dieter Rams, assembly system 571 and Chair Santa Lucia by Herbert Hirche, photo: Ursula Edelmann, about 1961

Dieter Rams, assembly system 571 and Chair Santa Lucia by Herbert Hirche, photo: Ursula Edelmann, about 1961

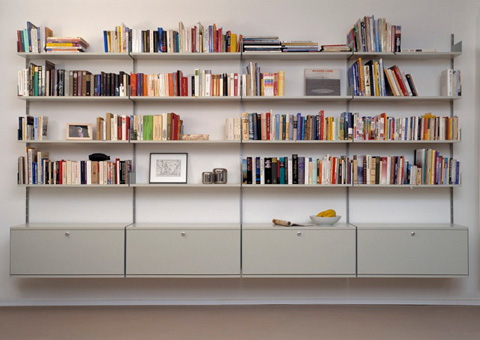

USM Haller Shelf by Fritz Haller, Paul Schärer

USM Haller Shelf by Fritz Haller, Paul Schärer

USM Haller Shelf by Fritz Haller, Paul Schärer

USM Haller Shelf by Fritz Haller, Paul Schärer

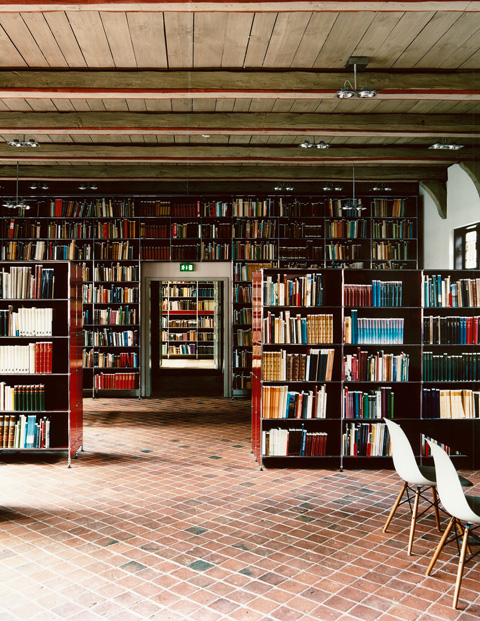

USM Company in Münsingen, Germany

USM Company in Münsingen, Germany

VI Triennale di Milano, exhibition design by Franco Albini, 1936, Credits: courtesy Photo Archive © La Triennale di Milano

VI Triennale di Milano, exhibition design by Franco Albini, 1936, Credits: courtesy Photo Archive © La Triennale di Milano

VI Triennale di Milano,1936, Credits: Photo Archive © La Triennale di Milano

VI Triennale di Milano,1936, Credits: Photo Archive © La Triennale di Milano

Regal 606 by Dieter Rams, photo: Vitsoe

Regal 606 by Dieter Rams, photo: Vitsoe

Veliero by Franco Albini, Cassina

Veliero by Franco Albini, Cassina

Joy by Achille Castiglioni, Zanotta

Joy by Achille Castiglioni, Zanotta

Gespanntes Regal by Wolfgang Laubersheimer, Nils Holger Moormann

Gespanntes Regal by Wolfgang Laubersheimer, Nils Holger Moormann

Dystopie „No-Stop-City“ by Archizoom, 1970

Dystopie „No-Stop-City“ by Archizoom, 1970

Serpent Shelf by Bashko Trybek

Serpent Shelf by Bashko Trybek

Serpent Shelf by Bashko Trybek

Serpent Shelf by Bashko Trybek

Plattenbau by Florian Petri, Kaether & Weise

Plattenbau by Florian Petri, Kaether & Weise

Plattenbau by Florian Petri, Kaether & Weise

Plattenbau by Florian Petri, Kaether & Weise

Michelberger Hotel, Interieur by Werner Aisslinger

Michelberger Hotel, Interieur by Werner Aisslinger

Books by Werner Aisslinger

Books by Werner Aisslinger