Beauty or bust?

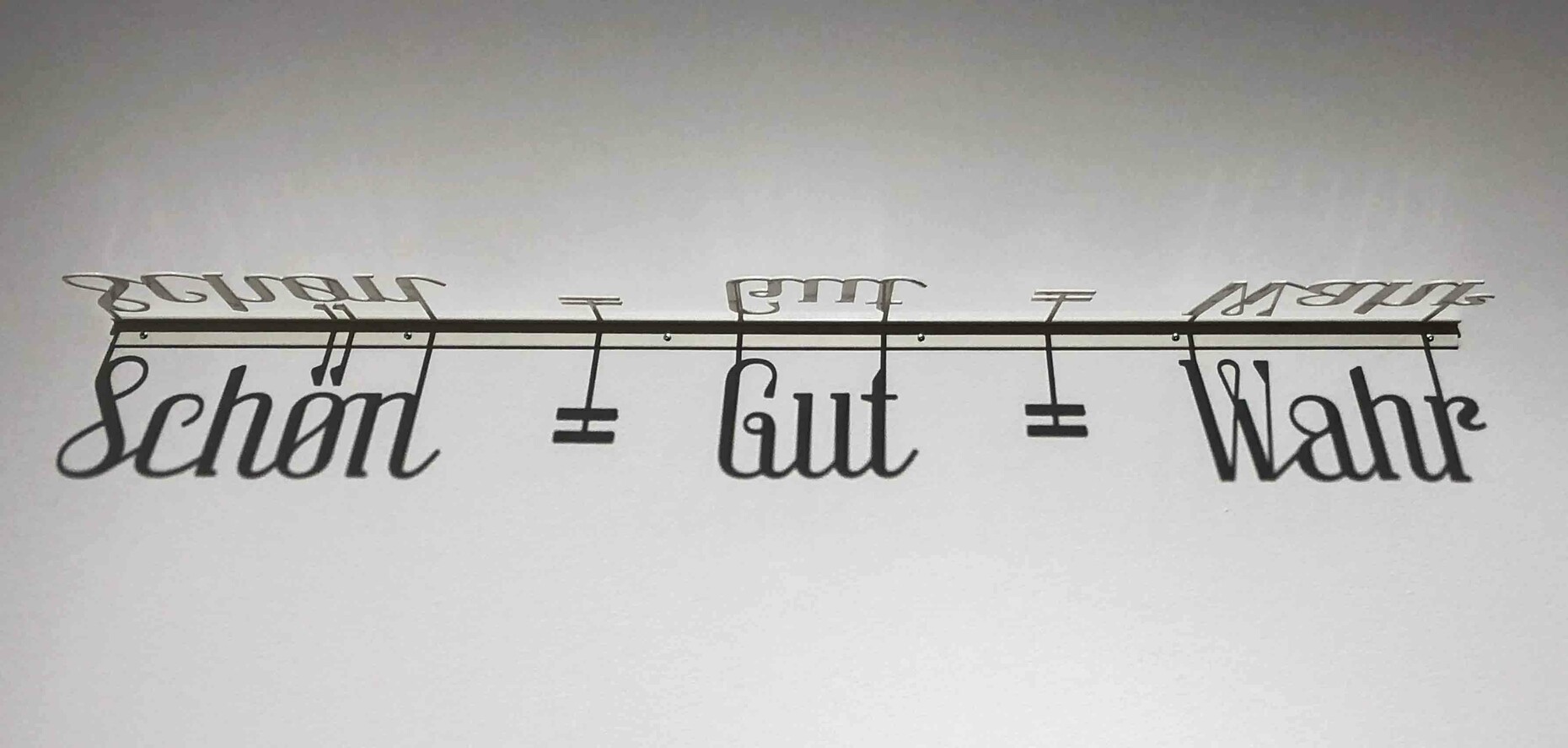

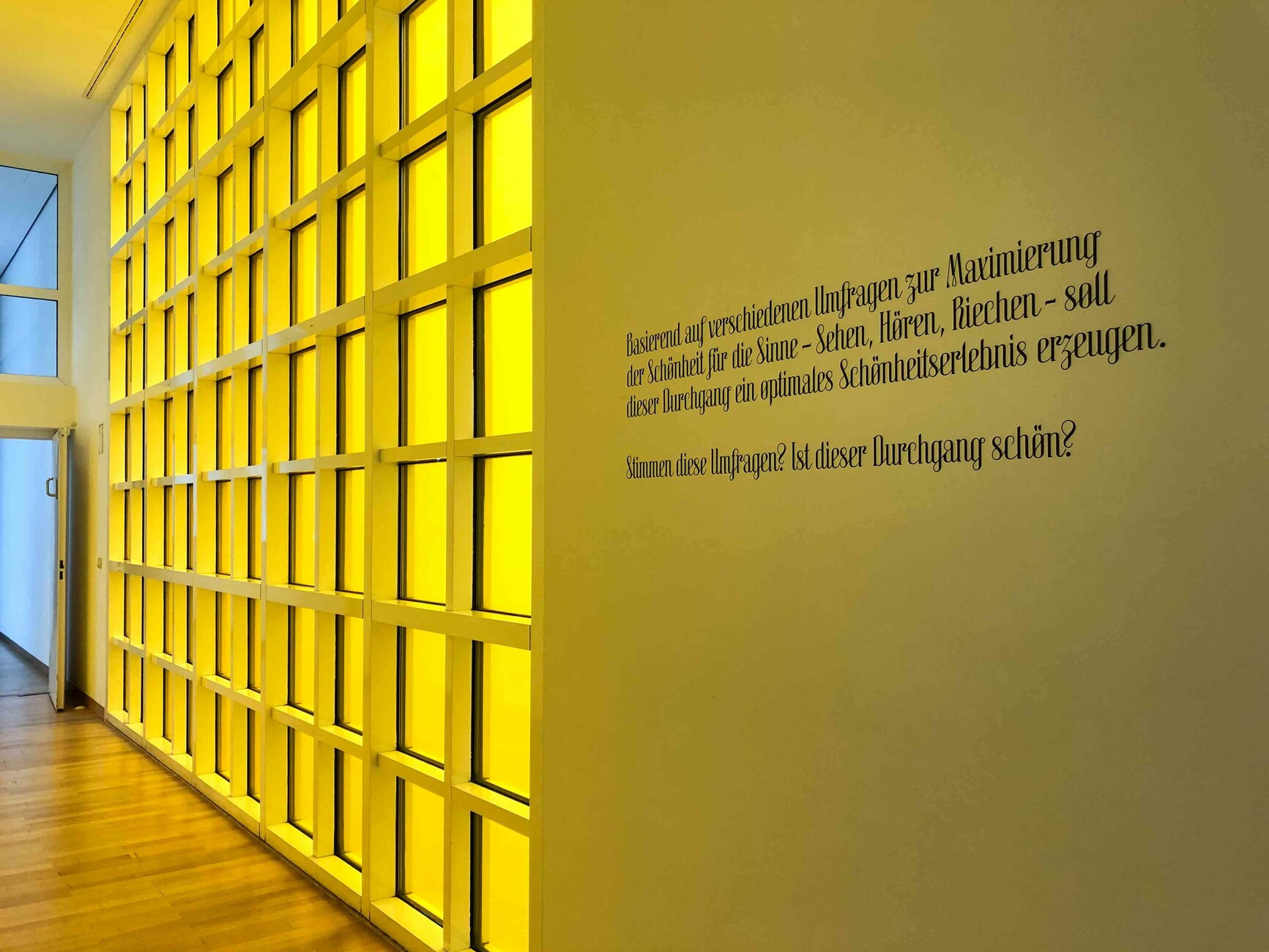

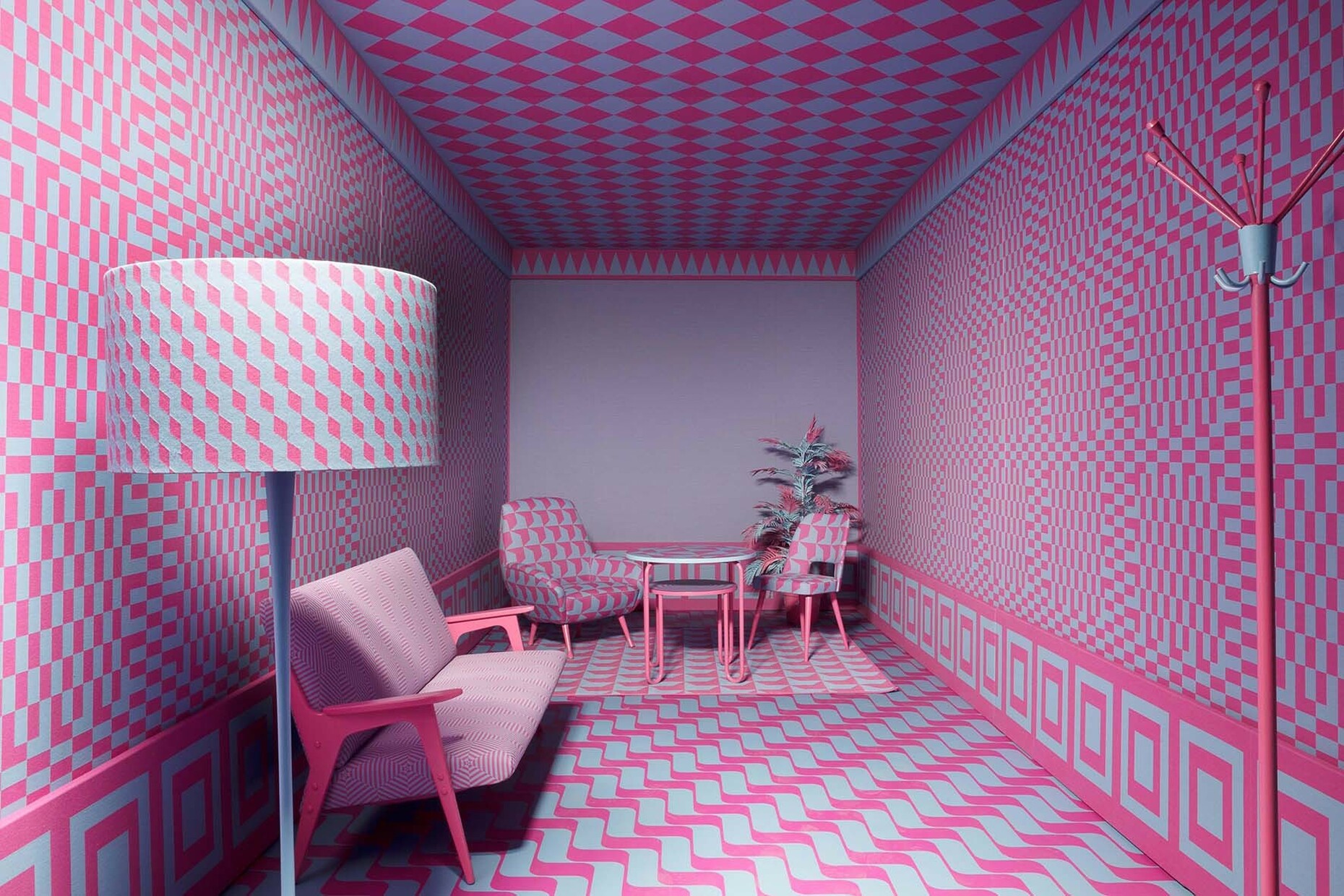

The ancient Greek philosopher Plato was convinced that what was good was beautiful and vice versa. He saw beauty as holding moral value. But does beauty remain synonymous with quality for us, who live over 2,000 years later? And how do we define “beauty” in design and architecture in our day? The duo Sagmeister & Walsh has dedicated an exhibition to the subject. Having started off at MAK in Vienna late last year, “Sagmeister & Walsh: Beauty” is now coming to Museum Angewandte Kunst in Frankfurt/Main. Much like their exhibition “The Happy Show,” in which Stefan Sagmeister and Jessica Walsh brought us many perspectives on the subject of happiness, “Beauty” is likewise hard to pin down. It rather seems as though the show were documenting a preliminary result of their creative research: The meta-theme is broken down into an interactive potpourri of 70 groups of objects and six topics (“What is Beauty,” “A Short History of Beauty,” “The Eye of the Beholder,” “Experiencing Beauty,” “Transformational Beauty” and “Contemplating Beauty”). The examples from psychological aesthetics, history, philosophy and the sciences, as well as graphic and product design, art, architecture and urban planning are linked by the simple credo: Beauty is function enough. “With the exhibition at Museum Angewandte Kunst we wanted to establish that beauty in architecture and design is not a superficial strategy, but deeply rooted in human existence. We wanted to spark a long overdue discourse on beauty and demonstrate that beautiful works not only give us more pleasure, but also function much better,” explain Sagmeister & Walsh.

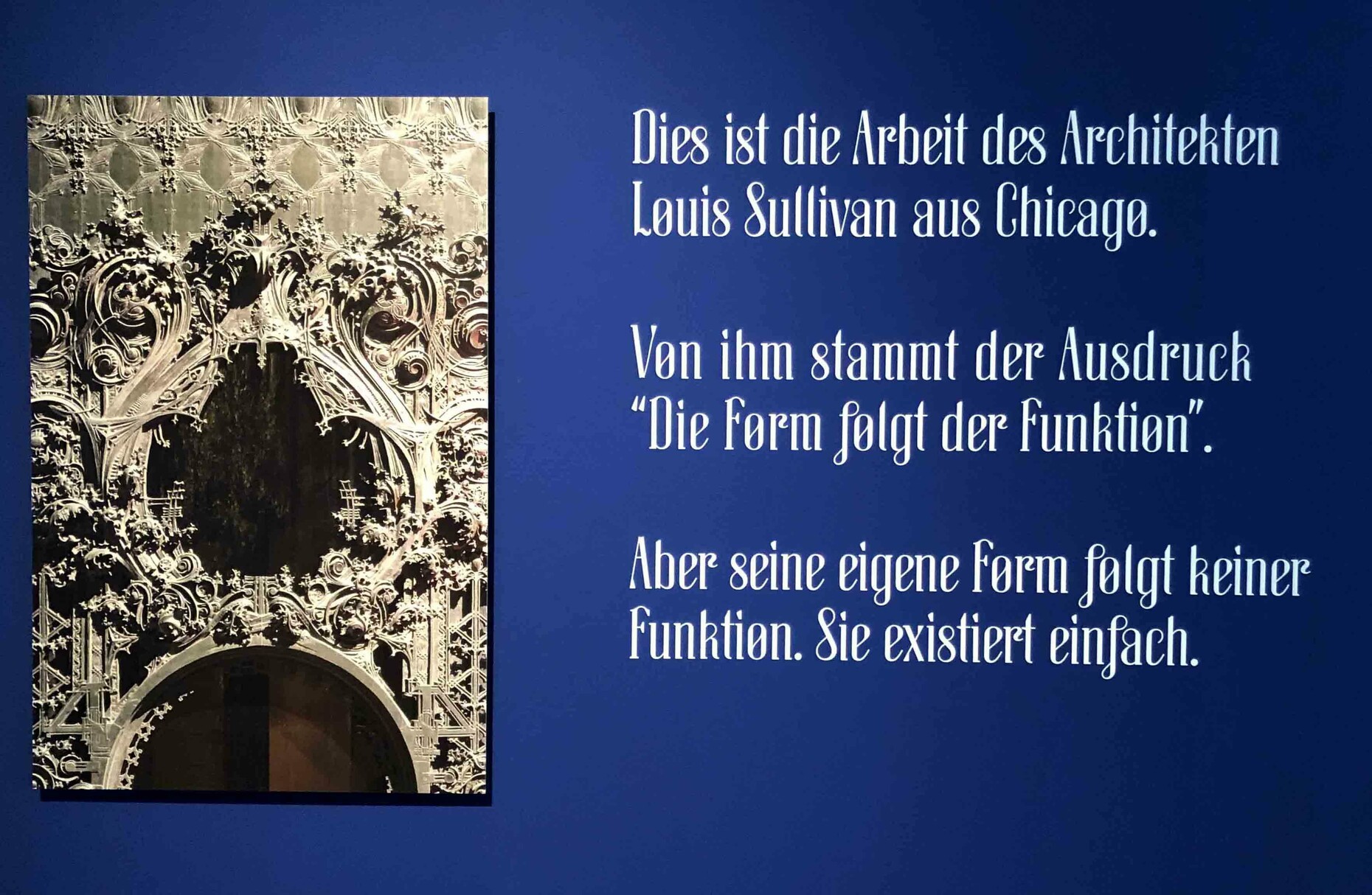

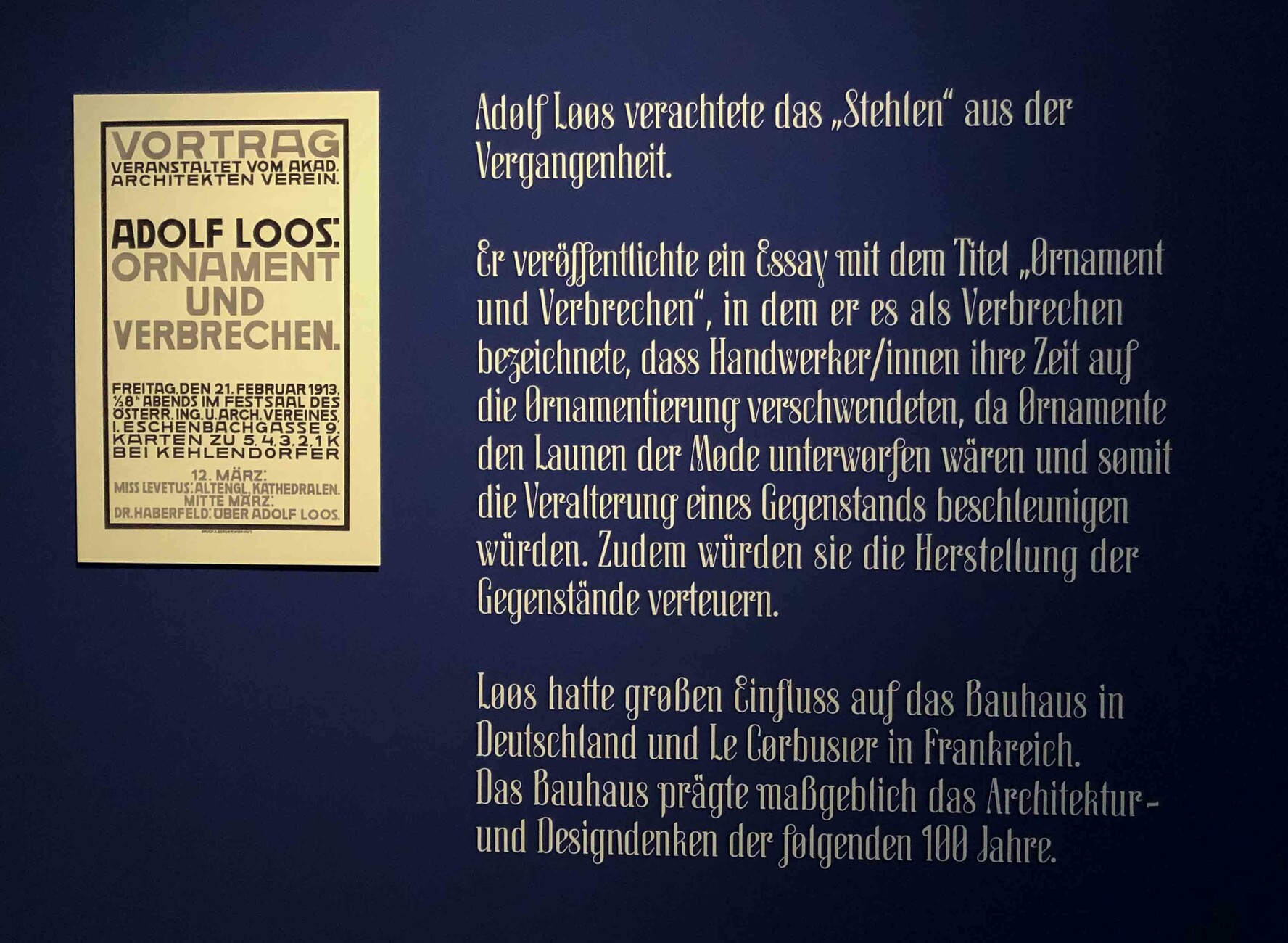

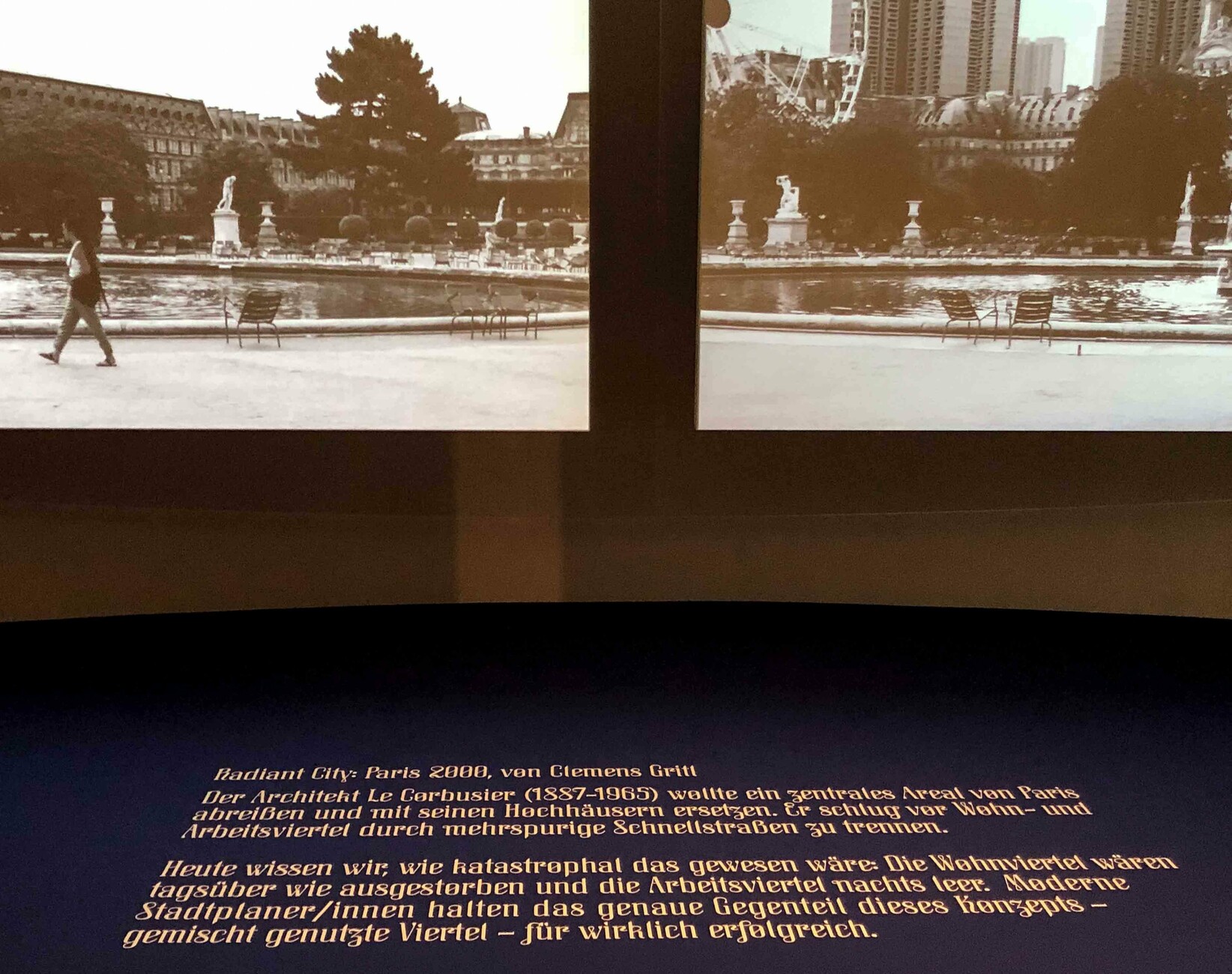

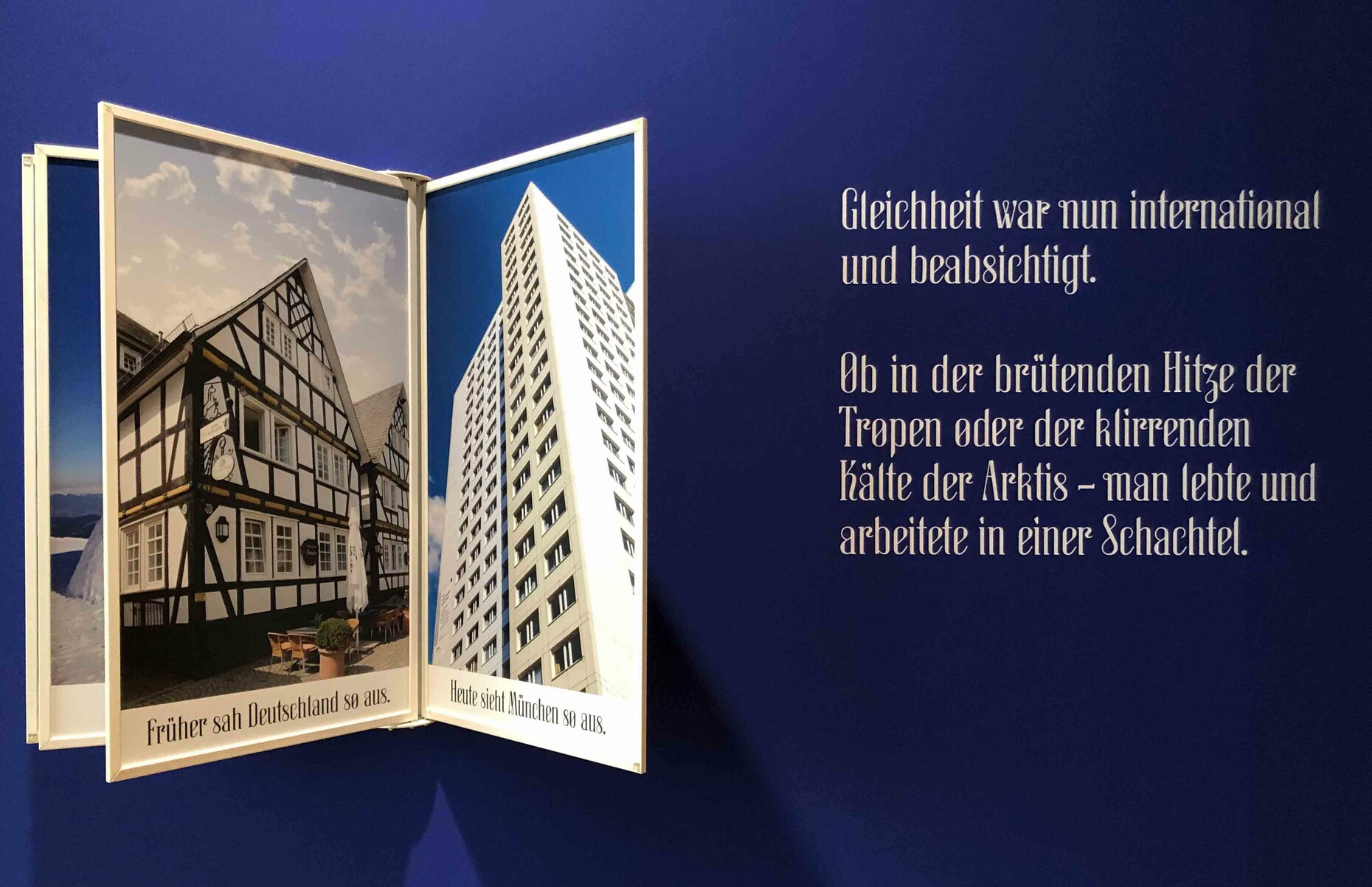

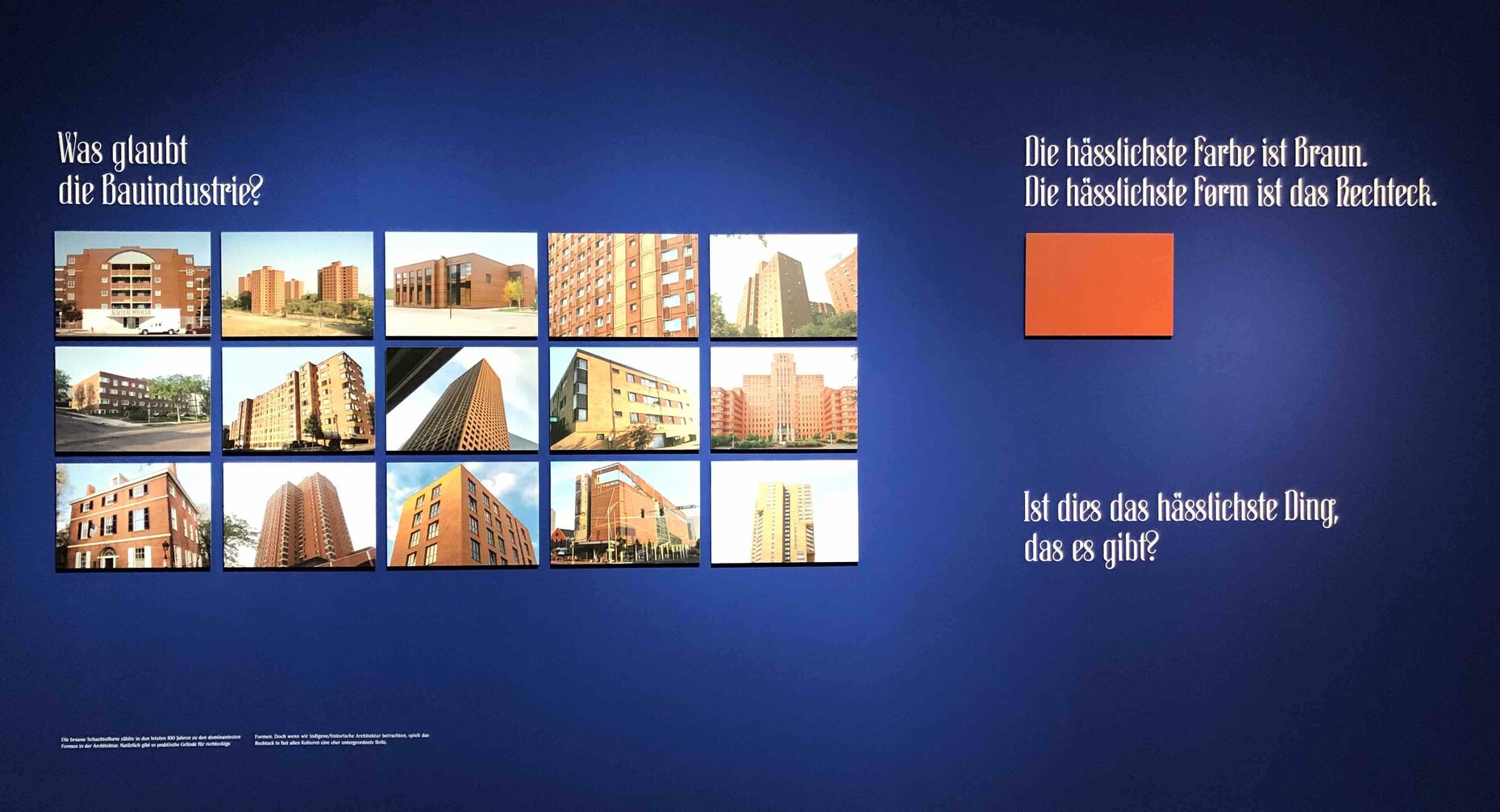

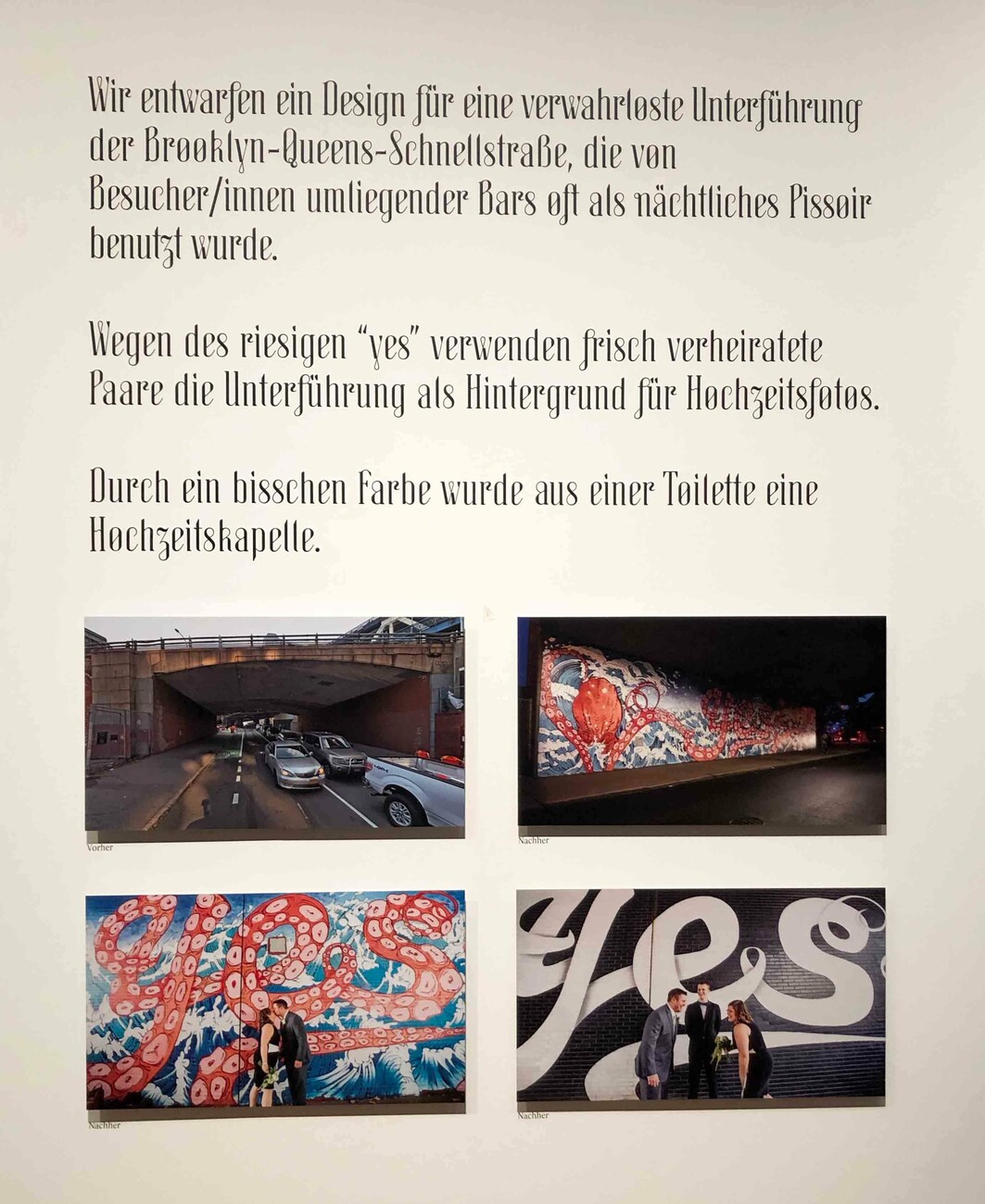

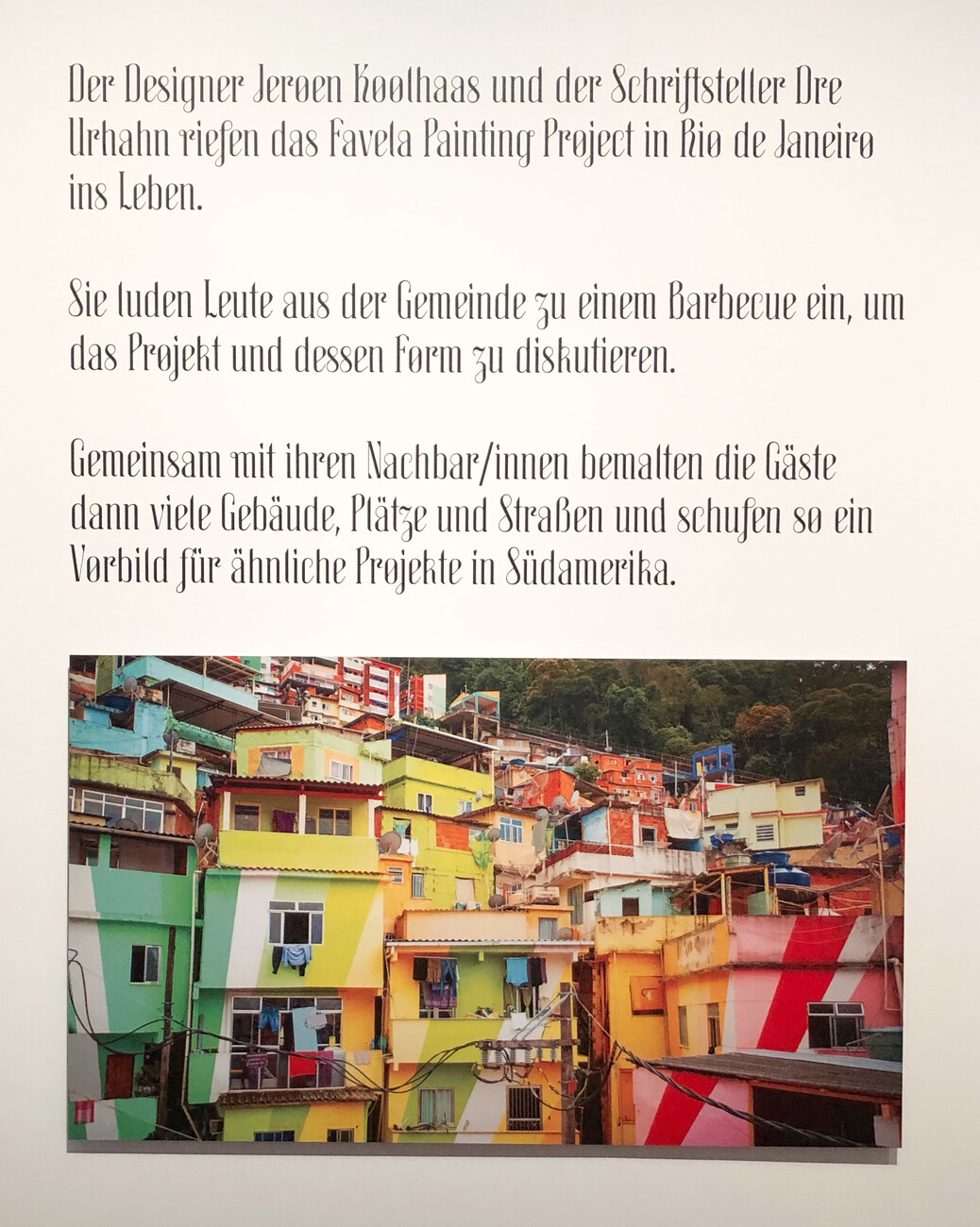

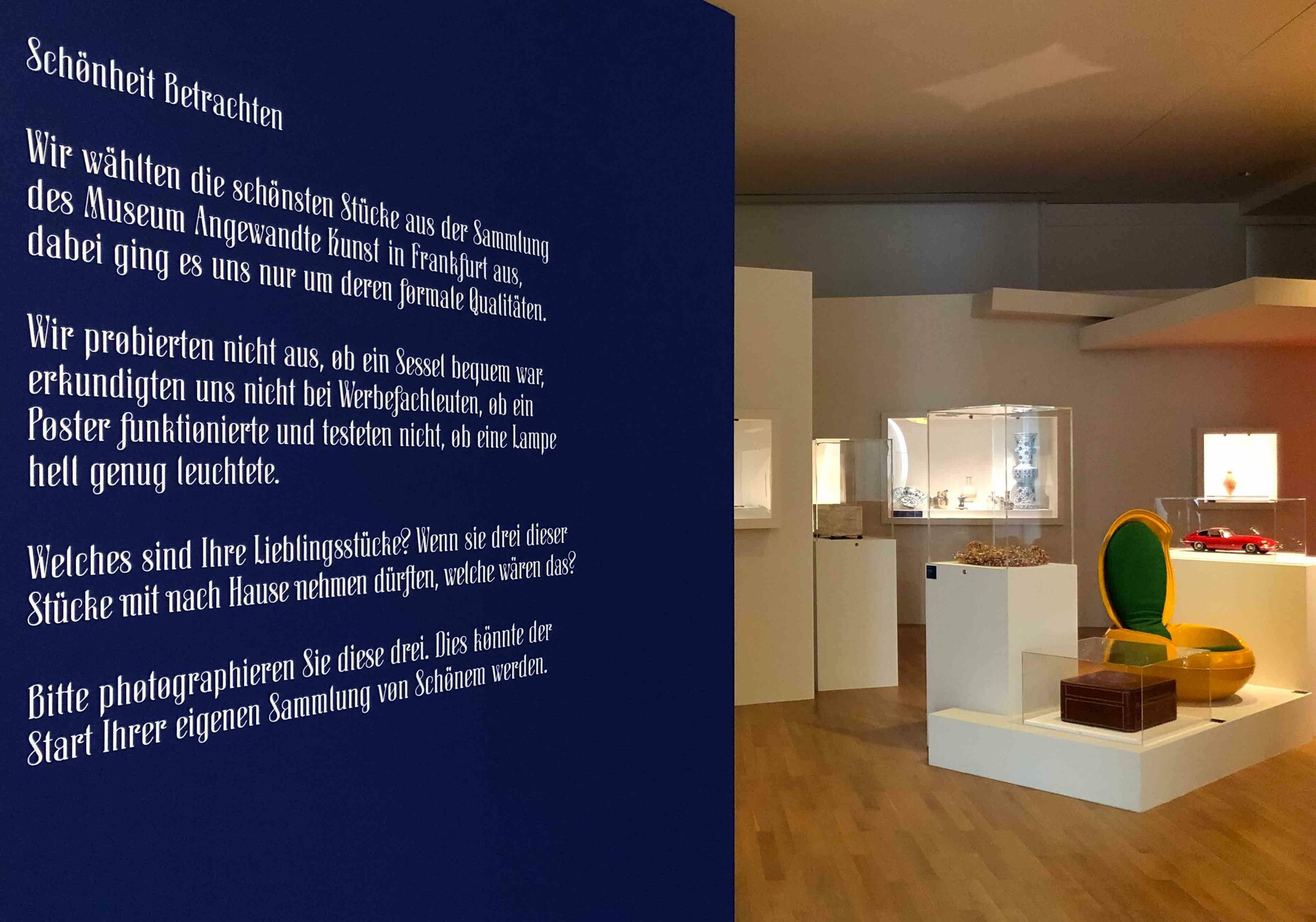

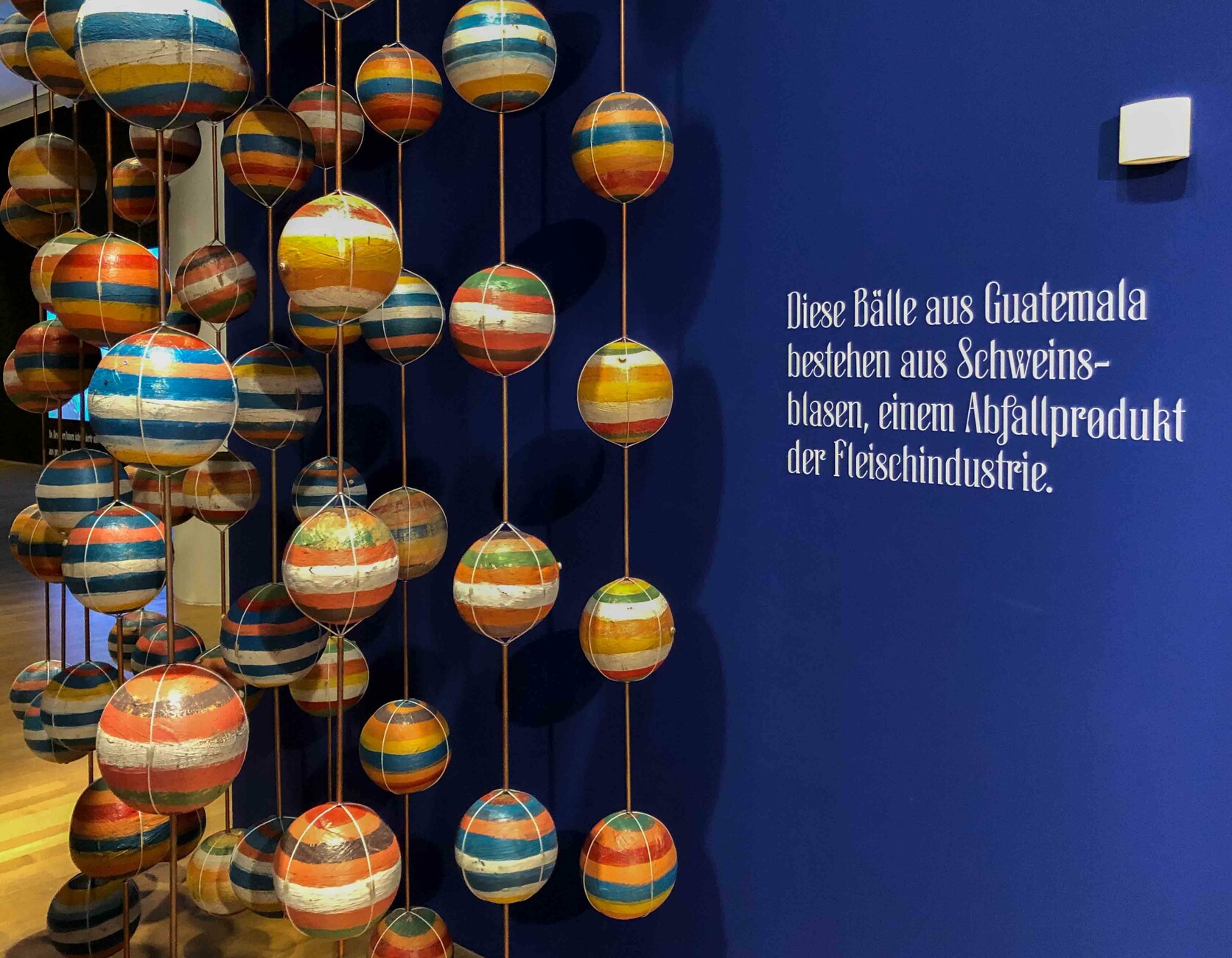

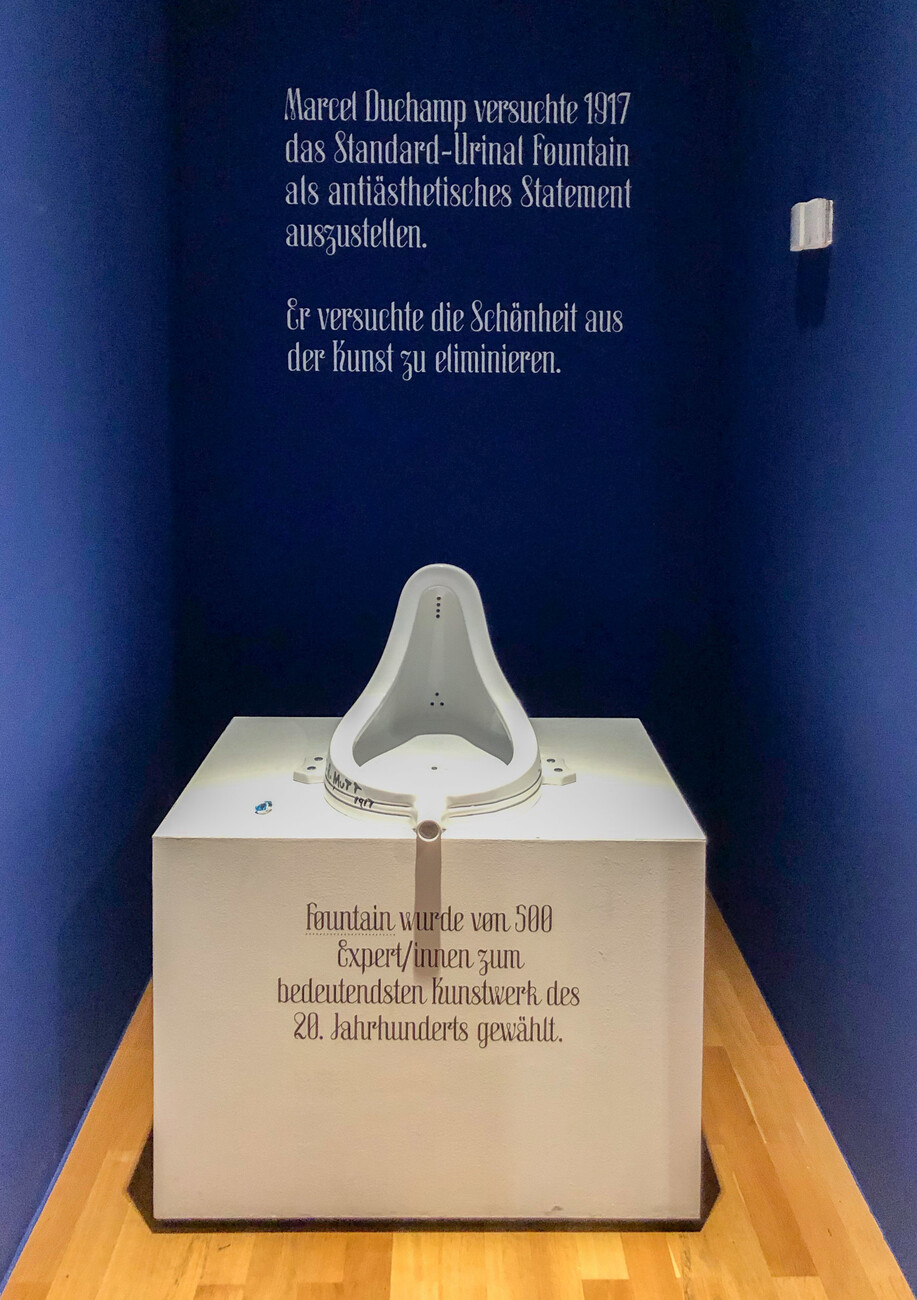

In order to emphasize this populist assertion, the duo denounces as meaningless the ideas of architects such as Le Corbusier, Louis Sullivan or Adolf Loos, who posited function as their primary goal. Sagmeister & Walsh believe: Functionalism had disastrous effects on society. They’re glad it didn’t prevail. Instead, their motto is: Beauty = quality of life. A fold-out panel on the topic of architecture and homogeneity tells us that the former Bauhaus student Fritz Ertl thought up the ultimate functionalistic rejection of humanity with his design for the Auschwitz barracks. Next to this, a short black-and-white film looks at Le Corbusier’s 1925 “Plan Voisin,” which included tearing down large parts of Paris’ old town in favor of an urbanist concept that strictly separated living and work spaces. A photograph presents a detail of a piece of wrought-iron work on the Carson Pirie Scott Building in Chicago with the note that while architect Louis Sullivan did coin the phrase “form follows function,” his own form did not follow function at all but simply existed. The clear lines that dominate the building created according to the principles of the Chicago School when seen as a whole, and the fact that its interior is characterized by a clear structure, are not mentioned. Whizzing through the history of architecture and art, viewers instead learn about the impact the two World Wars had on our sense of beauty in the arts. Visitors may then pick up chewy sweets from ceramic architectural models of the neo-Renaissance Vienna State Opera building, among others. Photos and short texts on projects in the public sphere explain how brightly painted architecture in urban environments persuades citizens that said architecture is now valuable and in turn worthy of protecting – all thanks to the decoration. We pass a luxurious chandelier made from household waste by designer Thierry Jeannot and painted pigs bladders from Guatemala, which presumably are here to show us that in design, materiality is of no great importance when it comes to aesthetic impact. We also get to feel for ourselves, by touching three cups produced in different ways, whether the manufacturing process can be identified by means of haptic qualities. Sagmeister & Walsh have also unceremoniously rearranged the design exhibits of the museum’s permanent collection according to purely formal aspects. Neither function, nor quality nor comfort feature in this line of questioning.

With a view to the small morsels of information made available for quick consumption like fast food bites, viewers soon realize: This exhibition does not claim to provide a comprehensive or in-depth view. It doesn’t answer any questions. Instead it constructs a daring hypothesis and tries to substantiate this with details loosely strung together from a range of subjects. In “Beauty,” Sagmeister & Walsh remain habitually superficial, inviting their viewers in a mainstream-friendly manner to explore the complex topic of beauty in playful ways. They contrast supposedly beautiful with supposedly ugly things, provoke a response with generalized remarks and try to give evidence of how beauty alone can help increase our quality of life. According to Matthias Wagner K, director of Museum Angewandte Kunst, the exhibition “does not aim to define beauty, but see what it might mean to us in the future.”

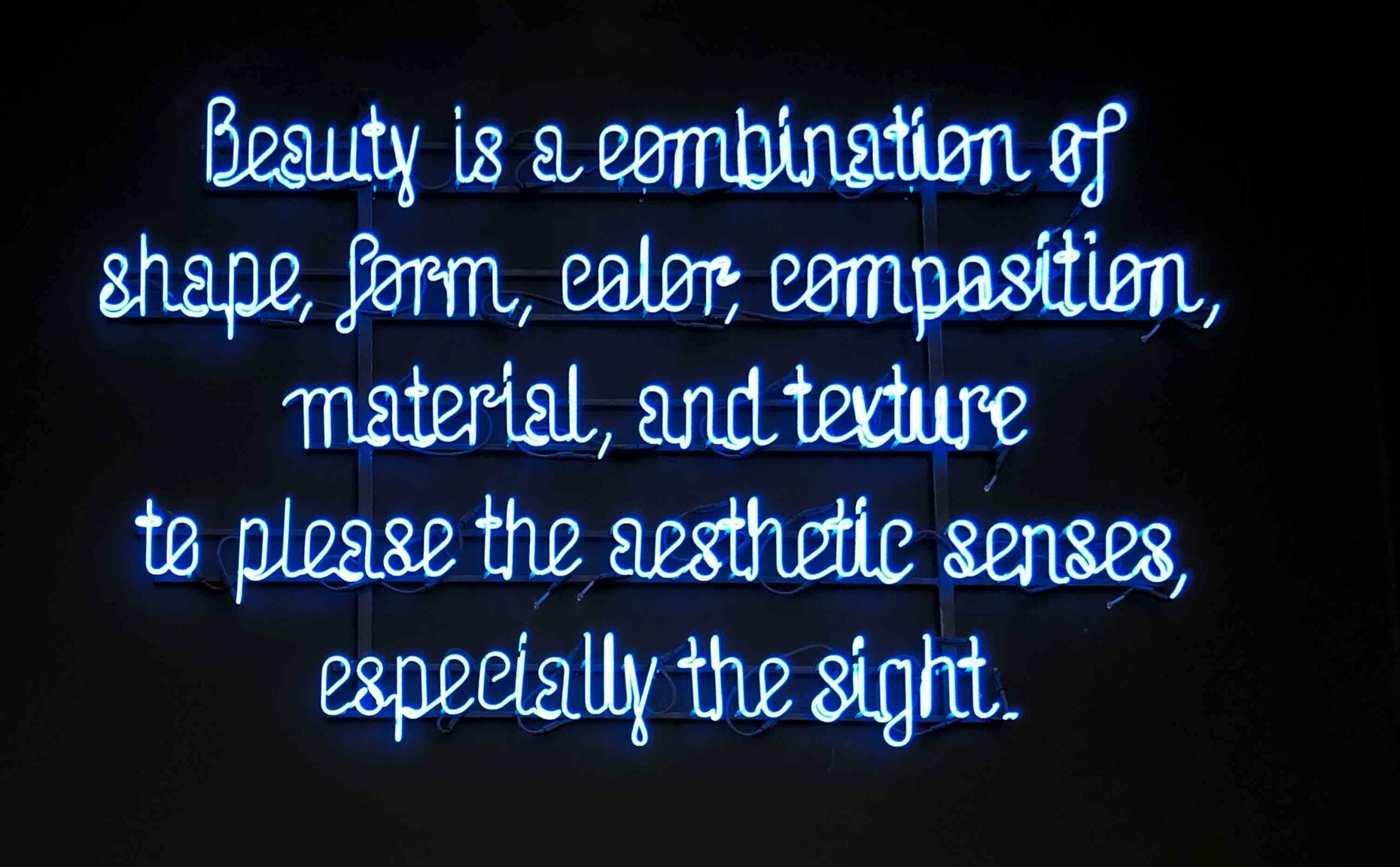

Incidentally, the fact that beauty does not suffice as the sole criterion for architecture and design becomes clear from the very start of the exhibition. Here, Sagmeister & Walsh define the term in large neon writing – as a combination of form, color, composition, material and structure. As it stands, one piece of the puzzle – beautiful or not – is not enough to create a coherent result.

Sagmeister & Walsh Beauty

Museum Angewandte Kunst

Schaumainkai 17

60594 Frankfurt

May 11 through September 15, 2019

Opening times:

Tuesday, Thursday through Sunday 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Wednesday 10 a.m. to 8 p.m.