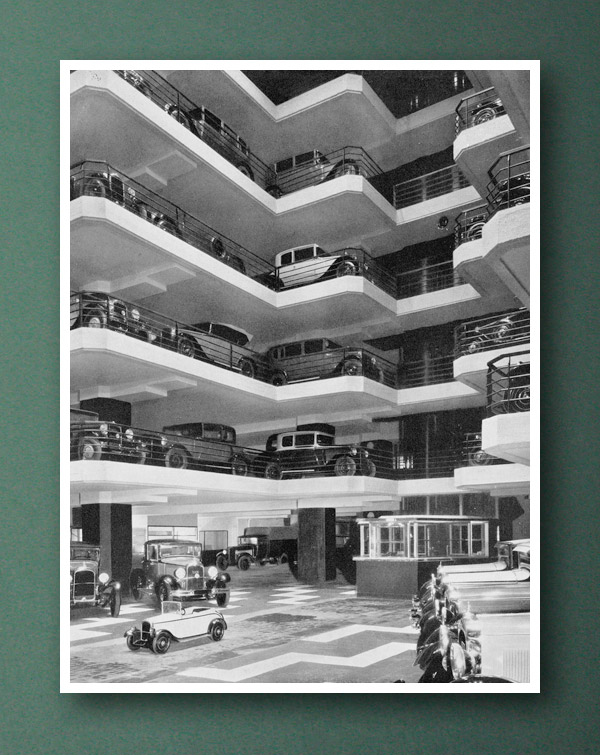

My kingdom for a parking space! Anyone who drives a car knows the problem. Be it a limousine, a SUV or a compact, your lovely motor not only offers you the freedom of personal mobility but also a massive problem: Where to place it when you've reached your destination? As soon as we switch over from being drivers to being pedestrians, we need a parking space. In fact we need more than that. We not only need one per car, but one at home, one at work, one when we go shopping, and one outside the fitness club. The list could be extended at will depending on the time of day and your personal agenda. Mobility spells movement, so we think. But in truth it is standstill that rules over everyday life, i.e., traffic that is not moving. Cars tend to stand around idle for about 23 out of 24 hours a day. Hardly surprising then that with the increase in motorization a new type of building has made inroads into our confined inner cities, a modern location where cars can be housed on several different storeys at once: the multi-storey car park. While the automobile still enjoys the strongest of business and social reputations, large garages have never had a lobby. Somber and monstrous, they have remained an unloved necessity. Despite the fact that engineers and architects have done their best to do justice to the standards expected of the building. However, the desired combination of maximum parking space and respect for the fragmented status of buildings downtown has rarely led to really satisfactory solutions. Or hasn't it? In his most recent book, author Joachim Kleinmanns sheds light on the history and typology of the multi-storey car park, on the technology used, their economic viability, and above all the aesthetics. In the process, the one or other structure initially derided as monstrous turns out on closer inspection to be so aesthetically and functionally logical as to later become a listed building. For example the rigid edifice built in 1956 at Neuer Wall in Hamburg and designed by Herbert Sprotte and Peter Neve or Cologne's first multi-storey car park, an elegant glass building by Ernst Nolte; then there's the edifice on Osterstrasse in Hanover erected in 1976 with its balcony-like staggered façade, or the temple-like Hillmann Garage created by Gerkan, Marg und Partner in 1983-4 in Bremen. The latter also designed two spectacular rotundas for Hamburg airport. Although the principle of the tower car-park has been known since the 1920s and an application to patent it even filed in 1960 by architect Kurt Höfler, the Hamburg car-park cylinders made a real splash and ensured the operators plenty of business. How different the fate of the Haniel Garage in Düsseldorf, built between 1949 and 1953. Wisely foreseeing the impending gridlock downtown, industrialist Franz Haniel had a large car park built on the grounds vacated by his factory on the eastern edge of town, between the interstate ramp and other thoroughfares. The structure and shape of the car-park cathedral created by Paul Schneider-Esleben reference the style of the 1920s. Two ramps suspended from steel beams run along the longer sides enabling drivers to reach the higher storeys. What was more decisive than the spectacular architecture was the idea of preventing downtown traffic from coming to a complete standstill. In the end, Haniel's idea of car parks on the edge of town did not win out. No one wanted to switch to public transport, not even to the exclusive shuttle-bus the car park operated, preferring instead to park within walking distance of the stores and offices. What many had feared, happened, or rather worse did: the automobile megalomania was not confined to the metropolises, but spread to towns and even villages, where people fought for the last square meter of parking space to lure the mobile purchasing power of the affluent society into the center. Which had consequences. In layer upon layer of car-park space, swiftly erected multi-storey facilities were soon merely functional edifices dedicated to one objective: to use as small a footprint as possible for as many vehicles as possible. Typical of such buildings is that the architects do not consider the existing buildings in the vicinity and usually opt for formal brutalism. There would've been alternatives. Since the 1920s and 1930s, long before car lifts and spectacular glass cylinders were celebrated as carmakers' display stands, towers or elevator car parks were technically long since feasible. Theoretically it would thus have been possible to create intelligent car parks in the heart of cities. But these ideas did not gain sway. Just another indication that the notion of the multi-storey car park fails less because of technical or aesthetic issues and more because of the lack of willingness among drivers to entrust their beloved vehicles to such a plant. In his book, Joachim Kleinmanns addresses a topic that not only raises aesthetic issues but above all socio-cultural questions. And even if on occasion he gets lost in overly precise accounts of details of the structures, his well-researched ideas are definitely worth dipping into. Parkhäuser

by Joachim Kleinmanns

Softcover, 208 pages, German

Jonas Verlag, Marburg, 2011

Euro 20

www.jonas-verlag.de