Even Le Corbusier enthused about the untreated surface in which the building process eternalized itself in the form of a negative imprint when he spoke of the "grandness of board-marked concrete". Anyone serious about concrete is a fan of purism. Sensual and archaic-looking fair-faced concrete celebrates an essential nakedness which also makes the load-bearing structure of the building "visible". Great craftsmanship is required to reveal the full beauty of concrete. It is often more expensive than natural stone and as such at times referred to as the marble of the 20th century. The fact that concrete can display itself as something with aesthetic appeal, and not just be hidden in the skeleton of a building is a trend which took time, however. The examples of monotonous mass architecture, for which the material basically stands, speak a different language. For the majority of the population concrete is the absolute evil-doer, the cemented cuss word for everything ugly and dismal in the modern age. Concrete has been celebrated over the centuries for its functional properties alone. The material has not been granted an independent aesthetic aura in spite of its construction properties.

Concrete with character

Despite his experiments with concrete, even the great Frank Lloyd Wright, who is revered like a saint as the inventor of modern American architecture, was unable to rouse ongoing enthusiasm for its aesthetic qualities. The aim was, as he wrote, to make something "timeless, fine and beautiful" from the "sewer rat". Wright breathed something of the spirit of "arts and crafts" into the sterile construction of concrete blocks when he developed four artful slabs with almost Oriental decoration. The most famous building constructed from them is Ennis House in Los Angeles, which was built in 1924 and became a backdrop in Ridley Scott's film Blade Runner. An ingenious concrete temple whose aesthetics at the time caused great offense.

The signature which architect and great concrete artist Paul Rudolph gave the provocative material also received little applause beyond the concrete avant-garde. The surface of Rudolph's famous cord concrete is roughly ribbed as if a plough had been dragged over a field. Rudolph used this surface processing for the first time in the 1960s at the Yale School of Art and Architecture, and later also in the Lindemann Center in Boston. For Rudolph, as with many others, it was about the plasticity of the material which he emphasized with his cord concrete as if the hands of the designer were perceivable in every detail of his monumental concrete sculptures.

Only a fine weather material?

Perhaps the surface design of concrete was first recognized so late because concrete ages very badly and often loses its beauty overnight. The material requires good weather - cold and especially rain do not agree with it. Concrete walls discolor quickly, becoming dark and patchy, forming cracks and orange-colored stains from corroded reinforcement iron. However, in recent years the improvement in the material composition of concrete has not only expanded the field of possible applications but also contributed to its aesthetic acceptance. A big step here was the invention of self-compacting concrete, "SCC" for short, enriched with silicate powder and synthetic mobile solvent so that the concrete ventilates alone from gravity and gains a finer surface. This new quality opens up further possibilities: The cool, clear aesthetics of SCC is a preferred material in spa and wellness oases as well as at home as a patina-forming concrete wall or monolithic concrete furniture which gains its own character over time - like a leather chair.

Concrete experienced a heyday as an added decorative element in Eastern bloc architecture, where wall images and relief plates became a real socialist ornament. Now concrete is booming as a design tool for facades and surfaces, without its intrinsic archaic expressiveness becoming kitsch. Fair-faced concrete is increasingly declared to be a sort of facade paper and communicative projection surface, and painted, written and printed on. It is a planar wallpaper on which much is imaginable. Relief-type drawings, photos and structures can be engraved into it. The printed concrete wall of the Eberswalde Library by Swiss architects, Herzog & de Meuron, looks like modern graffiti art.

Concrete doesn't always have to be gray

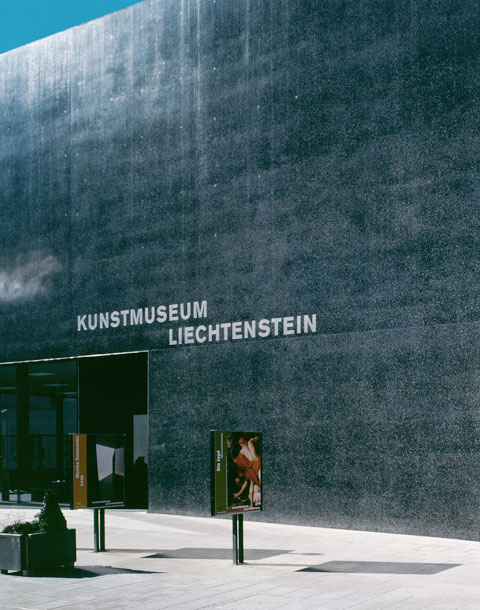

It is only half true that concrete has to be gray because it can also be effectively dyed. In the 1950s Alfonso Ossorio integrated a typical kidney-shaped swimming pool in a resplendent red-blue concrete geometry on Long Island. Today the most common coloration is a subdued brick red. The new Liechtenstein Art Museum in Vaduz shows more of the refined side of concrete with a black polished concrete facade sanded and polished so smoothly that it acts like a mirror reflecting its surroundings. This technique of sanding and polishing is also used for floors. For this purpose a rough-mixed concrete is usually chosen which once treated, looks similar to a terrazzo surface.

Tempting transparency

One of the sensations in the eventful history of concrete is so-called transparent concrete. This innovation which has been permanently enhanced in recent years with considerable improvement to the transparency, contains optical glass fibers. This transparent concrete is not just a decorative element. It can be used to erect complete buildings. Some even expect it to replace the dominating glass architecture.

Concrete can do many things. Although its versatility is often considered a character weakness it is precisely this ability to change - like no other material - which over and again enables it to capture the zeitgeist.

Orange County Government Center by Paul Rudolph; photo: Daniel Case

Orange County Government Center by Paul Rudolph; photo: Daniel Case

Yale University, Art and Architecture Building by Paul Rudolph, Paul Marvin; photo: Bruce Barnes

Yale University, Art and Architecture Building by Paul Rudolph, Paul Marvin; photo: Bruce Barnes

Yale University, Art and Architecture Building by Paul Rudolph, Paul Marvin; photo: Bruce Barnes

Yale University, Art and Architecture Building by Paul Rudolph, Paul Marvin; photo: Bruce Barnes

Yale University, Art and Architecture Building by Paul Rudolph, Paul Marvin; photo: Bruce Barnes

Yale University, Art and Architecture Building by Paul Rudolph, Paul Marvin; photo: Bruce Barnes

Church Saint-Pierre by Le Corbusier in Firminy

Church Saint-Pierre by Le Corbusier in Firminy

Church Saint-Pierre by Le Corbusier in Firminy

Church Saint-Pierre by Le Corbusier in Firminy

Church Saint-Pierre by Le Corbusier in Firminy

Church Saint-Pierre by Le Corbusier in Firminy

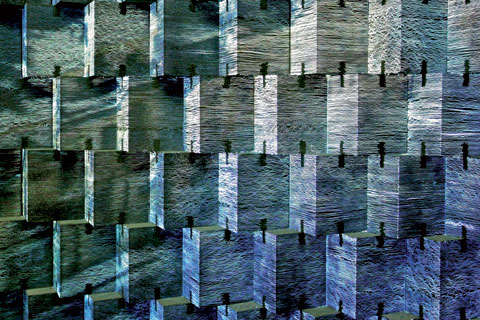

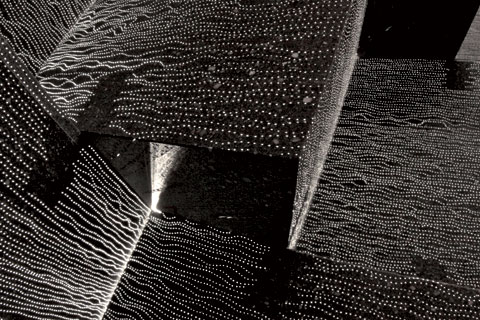

Transparent concrete by Luccon

Transparent concrete by Luccon

Transparent concrete by Luccon

Transparent concrete by Luccon

Ennis House by Frank Lloyd Wright in Los Angeles

Ennis House by Frank Lloyd Wright in Los Angeles

Ennis House by Frank Lloyd Wright in Los Angeles

Ennis House by Frank Lloyd Wright in Los Angeles

Library of Fachhochschule Eberswalde by Herzog & de Meuron; photo: Immanuel Giel

Library of Fachhochschule Eberswalde by Herzog & de Meuron; photo: Immanuel Giel

Library of Fachhochschule Eberswalde by Herzog & de Meuron; photo: Immanuel Giel

Library of Fachhochschule Eberswalde by Herzog & de Meuron; photo: Immanuel Giel

Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein by Morger, Degelo and Christian Kerez in Vaduz

Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein by Morger, Degelo and Christian Kerez in Vaduz

Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein by Morger, Degelo and Christian Kerez in Vaduz

Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein by Morger, Degelo and Christian Kerez in Vaduz

Transparent concrete by Luccon

Transparent concrete by Luccon

Transparent concrete by Luccon

Transparent concrete by Luccon

Transparent concrete by Luccon

Transparent concrete by Luccon