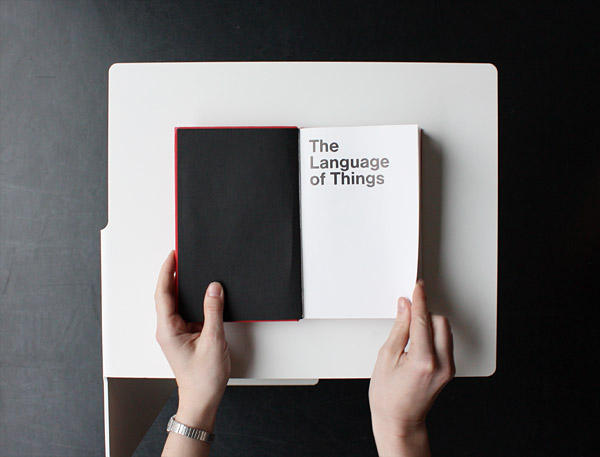

It is reminiscent of Hans Christian Andersen, where the Christmas tree and the tea-kettle talk to us. Only, as Deyan Sudjic says, in the twenty-first century things have lost their innocence. At the very beginning of his entertaining, witty book, The Language of Things, he declares laconically that we not only live in a world with more and more things in it, but that we use and utilise these things less and less. The consequence of this, as Sudjic sees it, is an extra portion of design. What John Berger in the Seventies, in his book Ways of Seeing, called "publicity", viz. the manipulation of desire through advertising, he would today, speculates Sudjic, ascribe to design. Design, says Sudjic, has become more complex, more calculated, and more intentional, acting increasingly as a sort of upward-appreciation code, which keeps the modern product world going and is injected into objects like a Botox shot. Unlike Berger, Sudjic is less concerned with a critique of consumption or capitalism. What interests him is the development of modern democratic design, the origins of which, in his view, lie somewhere between the work of the English social reformer William Morris and that of the French-American "snake-oil salesman" Raymond Loewy. Following in the footsteps of Loewy, says Sudjic, come designers such as Philippe Starck, who put themselves in the spotlight as cleverly as they do their products. On the other hand, he states, design has less and less to do with the creation of archetypes. There is less and less place for design approaches like those of a Dieter Ram, who, in the Sixties, described his legendary Braun appliances as discreet, invisible "butlers." Even if it is pretty obvious that Sudjic finds short-term effects, attained through styling, less illuminating, he basically makes no judgement. Rather, he operates a sort of design linguistics, quoting the Italian architect Ernesto Nathan Rogers, who as early as 1949 put forward a daring thesis: take a close analysis of a spoon, and you could tell the language of design which a society would use to build a city. Given the sheer abundance of mass goods today, Rogers' interpretations of design seem rather exaggerated, but an archaeology of everyday life is actually the very path which Sudjic is following. All this being said, Sudjic's book reads in part like a plea to take seriously a discipline at which, a few years ago, many museum directors were turning up their noses. Sudjic does not forget to mention what the then Director of the Tate Gallery, Alan Bowness, said in the Eighties when asked whether a planned design museum could use rooms in the Tate Gallery. "Lampshades do not thrill me", he announced disparagingly. However self-confidently Sudjic praises contemporary design as a key to explaining the everyday world, his attempt to distinguish art from design, adducing differences in their basic nature, seems forced. In this chapter, simply headed "Art", he leaves helpful historical digressions aside and relies solely on the distinction between the Useful and the Useless - asking why people generally attribute a superior value to the Useless; why at auction a Rietveld fails to achieve the price of a Mondrian; why, for the culture of the twentieth century, Le Corbusier's "Unite d'Habitation" is not valued as highly as Picasso's Guernica." Even the fact that contemporary design is currently so celebrated in art galleries, and more and more designers are turning out limited editions, does not lead Sudjic to believe that art already ranks on the same level as art in the value systems of its recipients. Sudjic, who is Director of the London Design Museum, sounds amazingly reserved when he says he sees only one thing coming in the wake of all the current design hype: a few "flamboyant" designs. "The Language of things" by Deyan Sudjic

Allen Lane publisher 2008, 224 pages