It is a good five years since Hans Stimmann retired as Berlin Municipal Building Director. But he's still definitely present in the city, in panel discussions, with projects, above all with the business premises and government buildings that have since the Wall came down been erect in line with his view on things: sober, clad in natural stone, "essentially straight lined rather than curvaceous", as he once defined his take n things. Or frequently unspectacular to the point of being boring. However, it would be wrong to exclusively remember Stimmann as the critical reconstructor, as the oppressor of Friedrichstrasse and Pariser Platz. The most interesting of things left behind from his era at the helm include a type of building that was definitely not invented in Berlin but was certainly massively supported in political and economic terms in the closing years of Stimmann's period in office: something that billboards told us was a "townhouse".

Downtown single-family dwellings, in portrait format

Narrow high houses the likes of which had never really been seen before in Berlin, capital city of the tenement block. Downtown houses for single families, long-side upwards, all of them four or five storeys high, and each of them a little bit different, depending on what the developer wants. Most of these townhouses are only 6-7 meters wide, but 13-18 meters deep. Out front there is just about enough space to park a microstrip of lawn, a Porsche, the trash cans and a porch. The wide-wheel SUV needs to be parked elsewhere, perhaps outside a second-home country manor. Berlin architect Almut Ernst once termed the dense houses a "simulated gap between buildings".

The townhouse as basic building block for European cities

Essentially, the concept of townhouses continues a long tradition that dates back to the early days of town planning: a family builds a house for itself in which it lives and works, on a plot of land in the heart of town. This buildings were initially referred to as the houses of "burghers" or even "patricians", before a fashionable label such as "townhouse" went and got stuck on them. Such houses were the basic building blocks for many European cities, extending from Lombardy through Augsburg to Amsterdam and Lübeck. Then there were the classic Hanseatic merchants' houses, with the offices downstairs, the family residence upstairs, and the store rooms out in the yard, or the crescents built in Victorian Kensington or Knightsbridge in London. The latter were the forerunners of today's townhouses, and not just linguistically speaking. Of course merchants no longer live in the townhouses, and the mixture of sales office downstairs, storage and home upstairs has been and gone. Berlin's townhouse inhabitants are primarily creative minds, freelancers, or well-paid employees. Among them attorneys and notaries, gallerists, doctors and plenty of architects, who have in part also relocated their offices to behind the facades they designed themselves. The fact that the developer, user and sometimes the architect, too, are one and the same person or entity forges an identity that fosters identification with the place.

Living and working in central Berlin

The most spectacular ensemble of such townhouses has arisen at Friedrichswerder, between the German Federal Foreign Office and Hausvogteiplatz, right behind the Kronprinzenpalais, and less than 500 meters from the Unter den Linden boulevard. A second building phase is about to launch behind the Kommandantur, and investors of all sorts have long since been constructing such groups of houses in Prenzlauer Berg, at Mauerpark, in Friedrichshain. Evidently this type of building is very much en vogue. And it is therefore not surprising that Hans Stimmann has now himself brought out a book on it, offering "planning assistance" as the title declares, an elaborate and beautifully made book full of samples of exemplary townhouses, with photos, ground plans and a section almost 100 pages long with a list of "building components", that presents porches living rooms, kitchens, bathrooms, stairwells and facades that have been realized. The book is a parade of what has been achieved, and a piece of propaganda, not to mention spinning the townhouse legend, which is in part Stimmann's own.

The volume presents some 40 examples, sorted by type: townhouses as ensembles and as terrace houses, multiple dwellings in building gaps, and finally so-called "town villas", standalone blocks containing more or less luxurious rented or owner-occupied apartments. It is no coincidence that among the architects who designed the buildings mentioned there are many who sympathize with Stimmann's conservative notions of the city and architecture: Klaus Theo Brenner, Bernd Albers, Hans Kollhoff, Kahlfeldt Architekten, Hilmer & Sattler und Albrecht, to mention but a few. Stimmann also mentions some representatives of a freer formal idiom, such as Grüntuch und Ernst, or Roger Bundschuh, whose spectacular black residential sculpture on Rosa Luxemburg Platz is one of the most exciting of the projects described.

Bidding farewell to huge blocks of flats

The introductory essay by Hans Stimmann, which bears the programmatic title "Bidding farewell to the Living Machine", also unfortunately includes many of the old chestnuts on why townhouses, not that this necessarily makes them wrong. Once again, we find Stimmann polemically attacking the construction industry functionalism of the Neue Heimat movement, the thoughtless industrialization of urban planning, and he illustrates this with ghastly images of large housing estates of the late 1960s and 1970s, that arose in fairly identical versions in both East and West, albeit with different ideological intentions. Once again Stimmann announces the "end of architectural Modernity", and once again he cites the theories of Aldo Rossi – and calls for a "back to the city", a back to tradition, beauty, convention.

Some houses mime Oxford, other's the Boulevard Saint Germain

If one considers all the townhouses realized in Friedrichswerder (and not just those presented programmatically) there's not a little irony at work here. Because not only does subtle variation reign there, it's a good example of an architectural free-for-all. There are strict plaster facades and rust-red brick house fronts. There are narrow-shouldered glass houses, vertical concrete blinds, and horizontal metal strips. And just about everything in-between. Some houses mime Oxford, others the Boulevard Saint Germain. An architectural exhibition of the early 21st century. And Stimmann is now presenting the catalog on it. Diversity is an expression of private freedom, and freedom is part of building townhouses, or so Hans Kollhoff claims. Stimmann speaks of an "individual urban architecture of houses of different typologies with a plural aesthetics."

Plural aesthetics

"Plural aesthetics" is a sweet moniker. And an indication that at the beginning of the 21st century the new citizenry opts to be just as little synthetic as an architectural convention. In fact, the townhouses in Friedrichswerder in Berlin are on average more fascinating as a sociological experiment than as a urban planning ploy. The decisive question must be how can one keep the young, high-income couples, most probably with kids, in the city or even persuade them to return and live downtown? It's a clientele that at the latest when in their late thirties and after the birth of the second child seem to have be magnetically attracted to the edge of town, to ever new estates full of terraced houses and suburbia that east into the countryside.

An end to towns emptying

For years, one study after the next has predicted the century-old trend to move out of cities is coming to an end, that the eternal move away from the center into the Nirvana of suburbia has no future. Subsidies for owner-occupied houses have been abolished, tax relief for commuter travel cut, and real estate prices in the housing estates of the 1960s and 1970s are starting to crumble; in fact, much would suggest that current life plans are significantly more urban than only one or two generations back. In particular, young women no longer wish to go to seed in suburbia or to spend far too many of their waking hours in gridlocks on the way to or from work, picking the kids up from the childcare center or school, or simply in order to go shopping. And the new silver-agers who have money to spare and lots of lust for life are rediscovering downtown. That's where their kids live, who have long since moved out of the home in the suburbs, that's where the doctors are, that's where the bookstores and libraries are.

Should the "townhouse" actually turn out to be a type of building that provides an appealing architectural shape for the desire for city life, then that would spell real progress. And then Hans Stimmann's manual would be of real benefit to us all.

For many years, Heinrich Wefing was the architectural critic for Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and is now an editor of the weekly "Die Zeit".

Stadthäuser

by Hans Stimmann

Hardcover, 367 pages, German

Dom Publishers, Berlin, 2011

Euro 68

www.dom-publishers.com

“Opernlofts“ in Berlin Mitte by Pott Architects, photo © Pott Architects, Bünck + Fehse

“Opernlofts“ in Berlin Mitte by Pott Architects, photo © Pott Architects, Bünck + Fehse

“Metropolenhaus“ in the Alten Jakobstraße in Berlin by BF Studio Architects, photo © BF Studio

“Metropolenhaus“ in the Alten Jakobstraße in Berlin by BF Studio Architects, photo © BF Studio

Living-area inside the Metropolenhaus, photo © BF Studio

Living-area inside the Metropolenhaus, photo © BF Studio

Living at Westhafen in Frankfurt am Main by Christoph Mäckler Architects, photo © Christoph Lison

Living at Westhafen in Frankfurt am Main by Christoph Mäckler Architects, photo © Christoph Lison

Town-villas in the Köbisstraße in Berlin Tiergarten, photo © DOM Publishers

Town-villas in the Köbisstraße in Berlin Tiergarten, photo © DOM Publishers

New building at Friedrichshain 28-32 in Berlin, photo © Stefan Müller, DOM Publishers

New building at Friedrichshain 28-32 in Berlin, photo © Stefan Müller, DOM Publishers

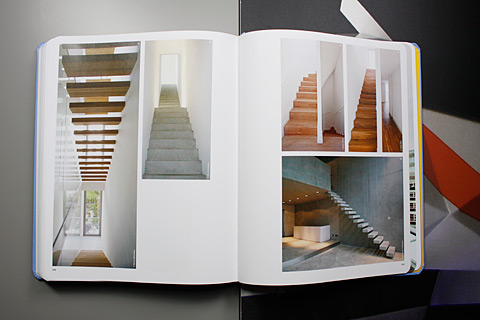

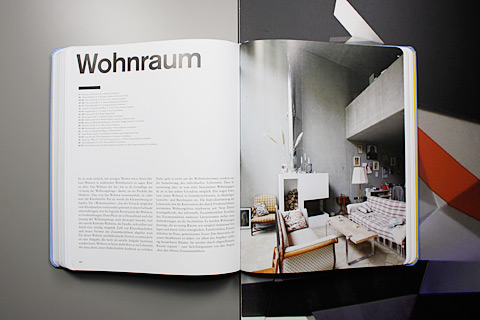

“Stadthäuser“ by Hans Stimmann, Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

“Stadthäuser“ by Hans Stimmann, Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

“Townhouse O15“ at Friedrichswerder in Berlin by Nalbach + Nalbach Architects, photo © Nalbach + Nalbach

“Townhouse O15“ at Friedrichswerder in Berlin by Nalbach + Nalbach Architects, photo © Nalbach + Nalbach

“Haus FL“ in the Bernauer Straße in Berlin by Ludloff + Ludloff Architects, photo © Werner Huthmacher

“Haus FL“ in the Bernauer Straße in Berlin by Ludloff + Ludloff Architects, photo © Werner Huthmacher

Single run staircase by Ludloff + Ludloff Architects, photo © Jan Bitter

Single run staircase by Ludloff + Ludloff Architects, photo © Jan Bitter

Idea of a single-room-house newly interpreted by Ludloff + Ludloff Architects, photo © Jan Bitter

Idea of a single-room-house newly interpreted by Ludloff + Ludloff Architects, photo © Jan Bitter

Building in the Ohmstraße by Christoph Mäckler Architekten in Frankfurt am Main, photo © Thomas Eicken

Building in the Ohmstraße by Christoph Mäckler Architekten in Frankfurt am Main, photo © Thomas Eicken

Housing in Caroline-von-Humboldt-Weg in Berlin, photo © DOM Publishers

Housing in Caroline-von-Humboldt-Weg in Berlin, photo © DOM Publishers

Plannings designed at the building-exhibition 1984/87 in Berlin, photo © DOM Publishers

Plannings designed at the building-exhibition 1984/87 in Berlin, photo © DOM Publishers

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark

Book photo © Dimitrios Tsatsas, Stylepark