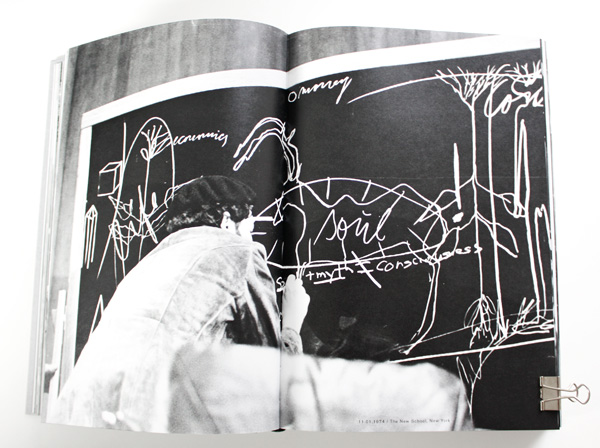

Joseph Beuys was constantly “on air”, constantly broadcasting. The first photographs in the “Beuys Book” show him on June 15, 1972, kneeling on the ground at his “Vitex agnus castus” Action in Lucio Amelio’s Modern Art Agency in Naples. Beuys spent almost three hours in the position, gliding his oil-smeared hand over a stack of copper panels (the conductors) until his body was so charged with energy that it vibrated. The sentence he uttered most frequently during this peculiar Action: “I am an emitter, I am emitting!” On March 30, 1973 Beuys wrote the following on a board in the Kunstverein Hannover: “The truth is a sparkler.” On January 9, 1974, he flew to New York with PanAm Airways accompanied by Klaus Staeck, patiently enduring the lengthy immigration procedures upon arrival at JFK. The following day, with the obligatory felt hat perched on his head and a heavy wool coat with a fur collar on his back, he gave his first “lecture” in the US to an auditorium at the New School that was filled to burst. A great number of artists were sitting among the students in the audience that day, among them the likes of Claes Oldenburg, Lil Picard, Al Hansen, Palermo and Ulrike Rosenbach to name a few. There are also photos of Beuys in Minneapolis, showing him with a handful of students: he is patiently explicating his social sculpture. A broad spectrum of images fill the pages of this volume: Beuys in a department store; Beuys in front of the Biograph Movie Theater in Chicago, where he randomly slipped into the role of legendary bank robber John Dillinger; Beuys with Klaus Staeck and Richard Hamilton; Beuys in his live-in studio on Drakeplatz in Düsseldorf Oberkassel, this time wearing a cap in place of his signature hat and reading the Westfalen-Blatt newspaper; Beuys with Nam June Paik, Henning Christiansen and René Block at Hamburg’s University of Fine Arts; Beuys labeling and signing some “assets” in the Musuem voor Hedendaagse Kunst in Ghent; or with Rolf Staeck in the studio producing “Multiples”, I could go on and on… No matter what Beuys was doing at the time, whether performing, chatting, holding a talk or signing small and often funny works, he appears strongly present, radiating concentration and cheerfulness. Leafing through this thick, gray volume full of mostly black-and-white photographs, the same question springs to mind again and again: Was Joseph Beuys, the shaman and untiring propagandist of an expanded concept of art, above all an “emitter” and grand communicator? The gray tome has been entitled “Beuys Book”, presumably an allusion to the famous “Beuys Block” in Darmstadt, and presents a compilation of photographs put together by graphic designer Klaus Staeck, printer/publisher Gehard Steidl showing Beuys in Düsseldorf, at a number of his Actions or on trips to Naples, Capri, Rome, Milan, Foggia, Pescara, Brussels, Ghent, Maastricht, Oxford, London or the USA. Arranged chronologically but otherwise subject to no particular order, the en passant snapshots were all taken between 1974 and 1986, the year Beuys died. Staeck and Steidl, who were extremely close to Beuys, accompanied the artist at exhibitions or attended his Actions continuously over these years. While the volume remains too fragmentary to constitute a biography in images, the panorama of an artist’s life that unfolds in these chance snapshots is at the same time both more and less than a biographical sketch of these years. As a personal documentation and homage made by two close companions, the book tells of someone who constantly strived, in his sculptures, Actions, Environments, talks and discussions, to reveal, convince and enlighten. As is made especially clear in these photographs, Beuys was certainly not joking when he said: “I am nourished by wasted energy.” The strength of this volume lies in its portrayal of Beuys as an untiring communicator, its weakness in the lack of any explanation of the occasions or reference to the Actions and exhibitions where these images were captured. The volume is rounded off with the last interview given in Beuys lifetime. The occasion being Beuys’ acceptance of the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize on January 12, 1986 in Duisberg, where the artist gave a rather strange speech, “My thanks to Lehmburck”, which given his death just days later on January 23, 1986, has since assumed the nature of a bequest. The interview was first published on February 1, 1968 in the German socialist publication, “Vorwärts”. In the speech as in the interview Lehmbruck is clearly present, and not just in the form of an echo from the past. For Beuys, his relationship with the sculptor was bound up with his decision to abandon his studies in Natural Sciences and turn his attention to art. This is presumably another reason why Beuys identifies a “threshold situation” in Lehmbruck’s work, a gesture toward to the future, something we can also find in Beuys’ own oeuvre. “I try,” says Beuys explaining his artistic approach once again, “to create new terms that reference the transformation of society as a whole and no longer cling to particular objects, particular figures.” Art that has been created in the wake of this statement certainly proved “Beuys the Emitter” right. Klaus Staeck, Gerhard Steidl

Book Beuys

Steidl Verlag, Göttingen, 2012

736 pages, bd.,

EUR 28.00

www.steidlville.com