The debate about light and saving energy has always hinged on quantity calculations and less on quality. For decades, the paragons of saving energy said lamp bulbs should be replaced. By energy-saving bulbs, or compact fluorescent bulbs. Just how pitiful and annoying artificial light can be emerged as soon as you tried to use one of these bulbs. By contrast, lamp bulbs were an old-fashioned standard product. Irrespective of where you bought them, the color rendition was always great, they had a specific light color, and a clearly defined output. Which is not true of the replacements. Electronics and modules spell versions of greater quality, power and duration, but this depends on many factors. Hamburg-based designer Peter Unzeitig, who has joined up with Ludwigsburg light planners Wesenlicht to devise the outdoor lighting for a new district on Stuttgart's Killesberg exclusively using LEDs, insists the transition from one technology to another must instead be seen as an opportunity to change our perception as a whole.

In the wrong light

This has happened with the ostensibly so reasonable compact fluorescent bulbs. Formally, they're imitations and all about retrofitting, as for all the new technology they rely on an outdated shape to be compatible with old luminaires and their screw sockets. Even if the new bulbs resemble Edison's lamp bulb in formal terms, unlike the latter it does not emit the whole color spectrum, resulting in many a measly mood. In its lower section there are electronic components that last longer than actual neon tubes. Making them far more expensive than light bulbs and generating a whole lot of electronic scrap. If that weren't bad enough, they contain small amounts of mercury, one of the most toxic materials and this means the production, use and disposal all require great care.

New paths into the light

When light planners, designers and users took up arms against the light bulb's abolition in Europe and Australia, it was already too late. What remained was the hunt for new, better ways of generating artificial light, whereby light-emitting diodes (LEDs) seemed to offer a way out. They're electronic semi-conductors, an established component since the 1960s, whose potential for generating light was first identified in recent years and has since been constantly expanded. Until recently, people thought LED were a nice idea and not more than that. For example, in 2006, Hamburg-based light designer and manufacturer Tobias Grau presented a prototype pendant luminaire called "Helena" that used LEDs. He was so unhappy with the costs and light output that he soon stopped the project. But Grau explored the process, slowly and gradually, and developed luminaires such as "Falling Star", that gives you light accents in the home, bars or lobbies. Grau also championed a greater awareness for quality among developers and consumers. Unlike many luminaire makers, he says that the key is to focus on LEDs' color temperature and color rendition to ensure things get seen in the right light.

Setting standards for new light design

"LEDs call for a completely different mindset," Grau now says. "They have a small light source, but you don't need to replace it. The luminaire as a whole is very efficient, but you have to make certain it's dazzle-free." Unlike neon tubes, you can not only direct the light, this is the precondition for using it meaningfully. To the benefit of designers and light planners, you can completely calculate the light in the virtual realm, test and optimize them in detail onscreen before the luminaires are used. The incredible progress in semiconductor technology meant Tobias Grau together with Hamburg-based light planner Christof Fielstette were able to meet extremely ambitious requirements when planning the light for a new type of building for the Hochtief branch office in Berlin. To date, there were hardly any economic arguments in favor of LED projects as the same power was required as for conventional illumination by fluorescent tube was identical. If an office relied on LEDs for the lighting, you needed as much energy – but the luminaires were more expensive. All that changed this year, as now there's an amortization period for LED projects, labeit a very long one.

In its branch offices, Hochtief brings together all the units in the region under a single roof. The construction company constructs the building itself, and later sells it off. Meaning economic feasibility and future viability are the deciding factors in the property retaining its value. The Hochtief executives insisted that the use of new technologies had to pay off in the long term. Moreover, they did not want to use customized luminaires for the project, but a mass-produced item with a guarantee and wide-ranging service backup. The light planner and manufacturer first of all devised a study to assess the project's chances of being realized. Close interaction led to Grau and Fielstette simulating a luminaire that met the business requirements. The result: the new "XT-A" luminaire with direct and indirect LED-created light. "The competition was not other companies," Grau comments in retrospect, "but the traditional fluorescent tube." Light planner Fielstette focused not only on how the light could be directed but particular on ensuring dazzle-free delivery so that users would accept the new technology. The decisive thing here: the interaction of high-quality LEDs, their positioning, the light direction using asymmetrical plastic elements beneath the LEDs and dazzle-free delivery by means of a grille that prevents any direct gaze into the strong, dot-shaped light sources.

Light buildings

Stuttgart-based Nimbus is viewed as a pioneer of comprehensive LED lighting. Unlike Tobias Grau, Nimbus uses acrylic glass backing for the LEDs with the light cone focused downwards. In 2007, the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce opened its "in-house house", an open spatial structure in the heart of an historical building. It was designed by Behnisch Architekten, and illuminated by 380 Nimbus LED module panels each bearing 400 diodes. In 2009, the ribbon was cut at the Unilever Headquarters in Hamburg's Hafencity, another Behnisch Architekten design, and it boasted Nimbus's "LED.next" luminaires. Both are regarded as pilot projects for energy-efficient illuminations. The latest mega-project by the Stuttgart boys is outfitting the ADAC head office in Munich, designed by Sauerbruch Hutton. An "innovative and sustainable concept in connection with completely customized solutions" essentially gave a key edge versus rivals, reports Dietrich Brennenstuhl, founder and owner of the Nimbus Group. Competitors mainly intended to use halogen illuminants, and the Hamburg Unilever model led to them winning. Now "Office Air LED" standard lamps at some 2,800 workstations deliver far more energy-saving light. Then there are pendant luminaires and flush-mounted ceiling units, too. Staff members can personally set how much direct light is sourced from the standard lamps, while the indirect portion is controlled centrally by a DALI system.

Sector undergoing change

With the flexible, innovative manufacturers, the former giants in the industry such as Osram, Philips or General Electric are feeling the squeeze. To date, only a small number of investors and private individuals are willing to focus on the new lighting solutions and their special features. And today, traditional companies are already turning out a large number of LEDs. However, it is the new, active medium-sized light-makers who are known for customized solutions and products. Group parent company Siemens wishes to shed its lighting division Osram, and an IPO is being prepared to flush money into the treasury to bankroll innovations. At the same time, ten percent of the total global payroll of 41,000 is to be cut. The stylized logo with the lamp bulb will also disappear. Recently, the newspaper "Die Welt" claimed that the world of Osram was in tumult. Philips Licht is investing heavily in acquisitions, with companies such as Luceplan and Modular Lighting already part of the portfolio of the Dutch group, which is already feeling sharp pressure on the price of its retrofit LED luminaires.

An LED is not a homogenous asset such as a lamp bulb. Every maker needs to find out what components are best suited for which product and can choose what the LED should do, how good the light it offers should be, and what light color it delivers and what the color rendition properties are. At present, the industry is trying to agree new standards for LED products and it will be up to the public to make sure the industry does not abuse the situation to artificially shorten the extreme life cycle of the semi-conductors the way the lamp bulb cartel once did.

"We're in the early days of the digitalization of light," says Michael Sturm of Messe Frankfurt's marketing section. And he's right, as this year's Light+Building will show where things are heading.

For the users, the luminaires of tomorrow are units with variable properties that thanks to digitalization will soon be progammable. Thinks look like being pretty opaque, choice will be harder, but before long we'll be able to see who acts to drive innovation, who opts primarily for traditional lighting technology, and who integrates the new technology into products first and foremost as an image booster. There are many paths into the new light.

light-building.messefrankfurt.com

Developed for Hochtief’s administrative building: Tobias Grau’s “XT-A-LED”, photo © Jörn Hustedt

Developed for Hochtief’s administrative building: Tobias Grau’s “XT-A-LED”, photo © Jörn Hustedt

The grille of Tobias Grau’s new “XT-A-LED” prevents you looking straight into the dot-like light sources, photo © Jörn Hustedt

The grille of Tobias Grau’s new “XT-A-LED” prevents you looking straight into the dot-like light sources, photo © Jörn Hustedt

Philips subsidiary Supermodular developed “Scotty”, a ceiling luminaire that uses a flat LED pane that can be turned asymmetrically and illuminates the entire room, photo © Supermodular

Philips subsidiary Supermodular developed “Scotty”, a ceiling luminaire that uses a flat LED pane that can be turned asymmetrically and illuminates the entire room, photo © Supermodular

The LED light in Tobias Grau’s “Falling Leaf” pendant luminaire is fractured by an optical lens and projected dazzle-free onto the table, photo © Tobias Grau

The LED light in Tobias Grau’s “Falling Leaf” pendant luminaire is fractured by an optical lens and projected dazzle-free onto the table, photo © Tobias Grau

Stuttgart-based luminaire maker Nimbus developed the “Office Air LED” standard lamp for the new ADAC head office in Munich, which was designed by architects Sauerbruch Hutton, photo © ADAC München

Stuttgart-based luminaire maker Nimbus developed the “Office Air LED” standard lamp for the new ADAC head office in Munich, which was designed by architects Sauerbruch Hutton, photo © ADAC München

The “Mantis” table lamp made by Slovenia’s Vertigo Bird consists of white glazed maple wood. The LEDs are integrated into a wood profile, photo © Vertigo Bird

The “Mantis” table lamp made by Slovenia’s Vertigo Bird consists of white glazed maple wood. The LEDs are integrated into a wood profile, photo © Vertigo Bird

“Iyon” is an LED spotlight system designed by Studio Delugan Meissl Architects for Zumtobel, photo © Zumtobel

“Iyon” is an LED spotlight system designed by Studio Delugan Meissl Architects for Zumtobel, photo © Zumtobel

The Belux “Verto”, designed by Japan’s Naoto Fukasawa, uses a single light source to generate both direct and indirect light, photo © Belux

The Belux “Verto”, designed by Japan’s Naoto Fukasawa, uses a single light source to generate both direct and indirect light, photo © Belux

Two dimmable LED panels on the upper and lower ends of Artemide’s “Column” standard lamp, designed by Ross Lovegrove, generate different lighting moods, photo © Artemide

Two dimmable LED panels on the upper and lower ends of Artemide’s “Column” standard lamp, designed by Ross Lovegrove, generate different lighting moods, photo © Artemide

The driver-less LED module “Airglow One” by Bremen-based makers GT BiomeScilt offers greater design potential, photo © GT BiomeScilt

The driver-less LED module “Airglow One” by Bremen-based makers GT BiomeScilt offers greater design potential, photo © GT BiomeScilt

LED technology in the shape of a lamp: “Bulb Right” by General Electric, photo © General Electric

LED technology in the shape of a lamp: “Bulb Right” by General Electric, photo © General Electric

LED panels for the latest generation of office luminaires prior to final assembly, photo © Thomas Edelmann

LED panels for the latest generation of office luminaires prior to final assembly, photo © Thomas Edelmann

Starting and finishing points of Tobias Grau’s designs, photo © Thomas Edelmann

Starting and finishing points of Tobias Grau’s designs, photo © Thomas Edelmann

Assembly of the new “XT-A-LED” luminaires at Tobias Grau’s manufacturing facility in Rellingen, photo © Thomas Edelmann

Assembly of the new “XT-A-LED” luminaires at Tobias Grau’s manufacturing facility in Rellingen, photo © Thomas Edelmann

View from below of the new LED office luminaires by Tobias Grau with funnel-shaped light focus. With a color rendition index (CRI) of 85 and a luminous color of 3500 K at 70 lm/Watt, Photo © Thomas Edelmann

View from below of the new LED office luminaires by Tobias Grau with funnel-shaped light focus. With a color rendition index (CRI) of 85 and a luminous color of 3500 K at 70 lm/Watt, Photo © Thomas Edelmann

A team takes the path from the first drawings through to the finished luminaire, and along the way lighting planners and designers optimizing the structure using computer simulations, photo © Thomas Edelmann, Stylepark

A team takes the path from the first drawings through to the finished luminaire, and along the way lighting planners and designers optimizing the structure using computer simulations, photo © Thomas Edelmann, Stylepark

Tobias Grau (left) and Tran Quoc Khanh, Director the Lighting Technology Dept., Darmstadt Technical University, photo © Thomas Edelmann

Tobias Grau (left) and Tran Quoc Khanh, Director the Lighting Technology Dept., Darmstadt Technical University, photo © Thomas Edelmann

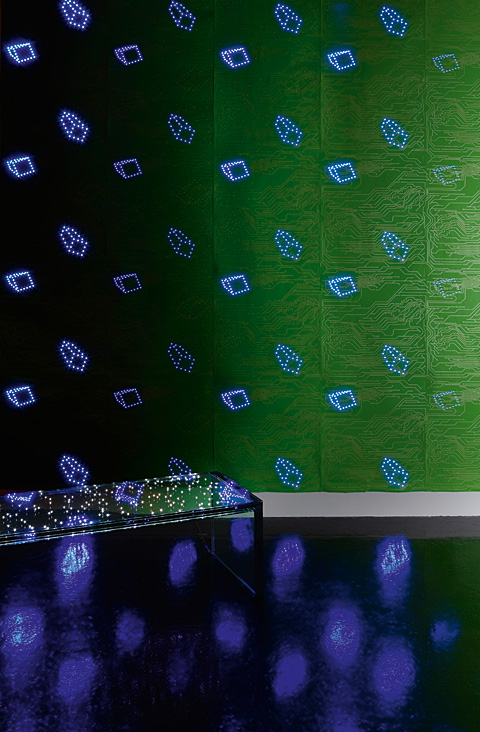

Each strip of Ingo Maurer’s “LED-Wallpaper” comes with 840 LEDs and generates about 60 Watt, photo © Ingo Maurer

Each strip of Ingo Maurer’s “LED-Wallpaper” comes with 840 LEDs and generates about 60 Watt, photo © Ingo Maurer

Version of the Tobias Grau “XT-A-LED” as a standard lamp, photo © Tobias Grau

Version of the Tobias Grau “XT-A-LED” as a standard lamp, photo © Tobias Grau

The “IO 3D” luminaire is part of the “Occhio” LED series created by designer Axel Meise, photo © Occhio

The “IO 3D” luminaire is part of the “Occhio” LED series created by designer Axel Meise, photo © Occhio

“Modul R 265 XL” LED pendant luminaire by Nimbus, photo © Nimbus

“Modul R 265 XL” LED pendant luminaire by Nimbus, photo © Nimbus

Retrofit LED by Osram: the “Parathom Classic A”, photo © Osram

Retrofit LED by Osram: the “Parathom Classic A”, photo © Osram