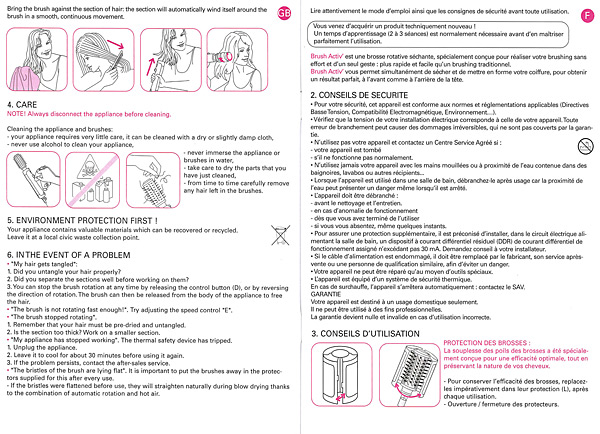

In summer 2010 Ergo switched to a rather "pleasant" advertising slogan to promote their services. According to one of the main theories, customers have had enough of advertising campaigns that leave them baffled with the feeling that the wool has been pulled over their eyes. Instead they want to understand things, they want assistance, they want certainty. "Can't you just settle my insurance policy rather than unsettling me?" asks the good-looking face of the campaign, casually reclining in his leather chair. Of course, an insurance policy that is able to meet this demand is merely the stuff of dreams. But this young man is however not alone in his search for greater clarity; this desire to understand and gain some kind of angle on such business is shared by many. It is something we think about day in day out. That's for certain, which is the last word one would use to describe our state of mind when it comes to insurance. Getting on angle on such matters is, however, an art in itself. This is a subject that also occupies many designers, albeit with less gimmicks. For product design, be it of coffee machines, battery-powered drills or websites, always takes the object's operation into close consideration, and also seeks to improve it. Moving beyond pure advertising and beautifying the appearance of a product's packaging. After all, an additional aim when developing new appliances (at least in the case of a design that is idealistic) is to simplify life. And this ideal is considered accomplished when there is no longer a need for instruction manuals or package inserts. But has design reached such a point? Are people able to get to grips with all of the objects that surround us? Are there everyday habit or practices that prompt us to improvise and test something out before reaching for the instruction manual? Admittedly, design production is dominated by one particular element, which seeks out "nice" new shapes and forms that make for better sales than the old ones; we call this style. Style is what penetrates the surface of public perception. This is how stars of the design world (who create highly impractical furniture) are quicker to make it into the glossy pages of magazines than designers who devote their painstaking efforts to making a shovel excavator easier to operate or creating an iron that doesn't require you to flood the whole apartment just to fill the water tank. Resonance is ever greater when a design breaks with supposed conventions; then it is even applauded by the arts pages. Veteran intellectuals are quick to rejoice at the end of some kind of hegemony, the overcoming of the everyday, and providing an array of such dictums. But taking on the – in fact much more difficult – challenge of satisfying existing conventions in terms of operation and thus succeeding in reducing product complexity, will hardly result in a single moment in the spotlight. The stereotypes are obvious: Artistic heroes are celebrated, while "boring" engineers and usability designers supposedly just fiddle around with details in slavish adherence to the principles of functionalism. But is that really the case? And if so, will it remain so? Anyone glimpsing at today's instruction manuals is likely to have a great time. We are greeted by for the most part useless images showing us what we have to do in order finally to persuade this particular piece of technology to do something useful. In principle, these illustrations demonstrate what the designer didn't quite manage to include in the design: Namely, that the user immediately understands what they are supposed to do with the contraption at hand. The graphics that decorate this duty-bound printed material are there to step in where the product designer failed. The most astonishing part is that hardly anybody has taken the time to systematically examine this type of media. Jasmin Meerhoff is therefore an exception to the rule: The cultural and media history of the instruction manual as depicted in her recently published book "Read me!" provides a comprehensively outlined perspective on the subject. She begins with an in-depth look at the genre of explanatory texts and images. Designers who have perhaps addressed this topic on a fundamental level, ergo on a philosophical one, may well find themselves once again confronted with key terms from Heidegger's concept of "Zuhandenheit" (ready-to-hand-ness) versus those of simple availability; a cornucopia of terms that crop up time and time again in the context of interface design, usability and texts on man-machine interfaces; and approaches that would immortalize Martin Heidegger and his arguments surrounding the world of objects. Surprisingly, this excursus manages to get by without any reference to media philosopher Vilém Flusser who penned a great deal of educational material for designers and continuously fired up skepticism toward technology – without spreading bad faith in the process, "The Lever Strikes Back" comes to mind here. "Read me!" is the outcome of a Ph.D. dissertation written at the Bauhaus-Universität in Weimar and a great asset to the media landscape, one that is good-humored and at times close to entertainingly written, at that. This was certainly a brave step; after all nothing is more dangerous within the academic world than comprehensibility and amusement that also seeks a putative reputation. (Whereby the complexity of an academic text, as I might add, is comparable to an engineer's passion for technology, which leads them to pay more attention to the object itself than the end-user) All the same, her approach of systematically sounding out the problems behind instruction manuals is extremely eye-opening. In conclusion she demonstrates that these sketch-like explanations actually date back to Leonardo da Vinci and have been gradually honed and altered over the years. In some parts, the author was unable to resist offering comic commentary and the text is also peppered with somewhat dramatic surges. For example, an account by one technical writer responsible for the production of instruction manuals who describes how little importance was attached to editing these publications in his company: "Five prototypes were made for each new product. Three of these were sent off for endurance tests, one to management and the fifth to the photographer. We didn't even get one to look at." To what extent a little more effort would have improved the final result is however a question that will remain unanswered. But looking to the past may well serve as basis for speculation about the future, for since that time an increasing concurrence between use and acquisition has developed. While in the case of television sets and video recorders from times past it was still deemed necessary to proceed by first reading and learning, then using the product, this linearity appears to have become obsolete. Trial-and-error now takes precedent over expertise: A phenomenon that is to be observed most notably in the area of communication devices. Leading the way, Apple's products continue to demonstrate new approaches to product use. iPhones, iPads and all other iProducts have long since done away with instruction manuals. And when Apple finally releases their first TV, we definitely won't need manuals to become masters of the a/v universe. This may be due to the fact that the company in question did not in the computer sector define itself in terms the machines' technical performance. Instead it focused on use, pleasure, fun and entertainment value – preferring not to uncover any ideological contradictions. Perhaps this culture of "giving it a go" has come to replace the concept of learning something once and then repeating it over and over. For the expectation that we can look at a device and automatically be able to operate it and know everything about it, seems completely realistic in today's world, as does our hankering for an insurance policy that we understand. Read me!

By Jasmin Meerhoff

Paper back, 152 pages, German

Transcript, Bielefeld, 2011

Euro 19.80

www.transcript-verlag.de

The following pictures are not presented in the publication "Read me!", but were selected by Stylepark.