ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Exciting times

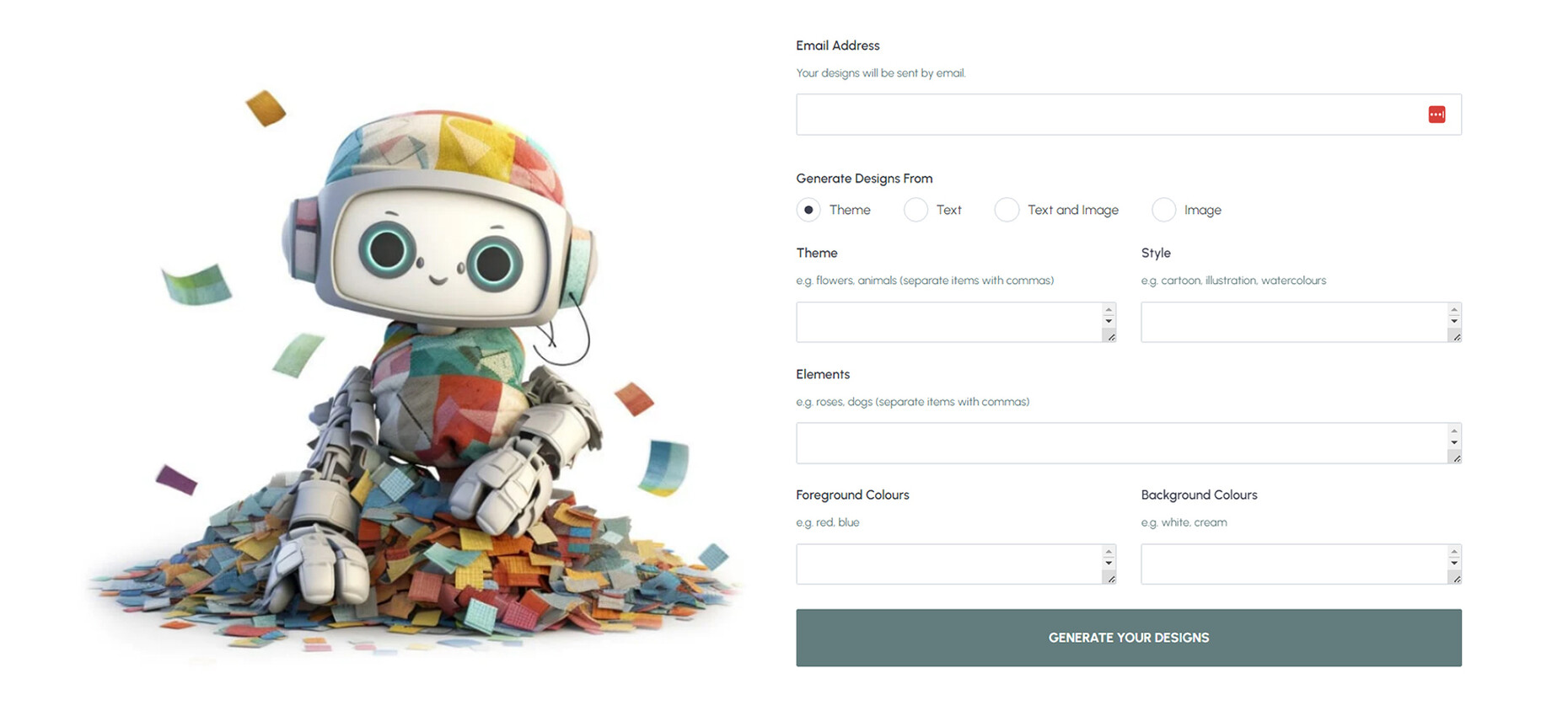

Anna Moldenhauer: FabricGenie enables users to upload an image of a space and use this as the basis for the AI to then give you recommendations for the textile fit-out. How exactly does that work?

Danny Richman: That is the most frequent way the service is used. In parallel to it, users of the AI can also describe the design they have in mind, such as “William Morris style, floral print with birds on a dark green background”. Moreover, there is an option enabling you to upload sketches that FabricGenie then utilizes for inspiration and translates into a fabric design.

Does the service come at a cost?

Danny Richman: No, it’s all completely free of charge. Users don’t even need to register in advance, and the tool is openly accessible to everyone. You only incur costs if you want to transform the design into a physical product, meaning a piece of fabric, curtains made to measure, cushions, etc.

So who’s behind FabricGenie?

Danny Richman: A company called The Millshop Online; they’re retailers for curtain fabrics and home textiles. However, the products the company offers are independent of FabricGenie.

Where does the service obtain the data it requires for the designs?

Danny Richman: When trying to explain the function of generative AI, I like to cite an example from the field of text, as the process involved is the same: Let’s assume I use ChatGPT and ask the tool to formulate this interview for me. The AI does not copy an existing article but is trained in using a huge volume of text. In other words, it relies on a massive amount of information that is available on the Internet in order to understand the connection between words in an overall concept. Put differently, the AI analyzes, for example, that there is a connection between the words dog and bone, dog and cat, because they are often used in one and the same context. This structure is what the AI takes up and transforms into numbers that represent the relationship between the words and the concepts. If I now place a request which includes the word “dog”, the AI will weigh up which word follows most frequently in the texts that it analyzes. Then, in line with this system, it adds word to word in order to find the most probable answer to my request. In humans, this functions on the basis of everything we have seen or experienced up until that point: If I ask you to draw a pattern, the basis for that will be the memory of every design you have seen in your life. The image inventory is assembled piece by piece, and that applies to AI just as it does to people. In the case of AI, there is no direct relationship between what it was trained on and what it produces. If I give FabricGenie the instruction: “Create a floral design in the style of William Morris”, it will not match the William Morris design; rather, the result will merely resemble it.

”What you’re seeing at the moment is the worst version of AI there will ever be. The degree of detail the AI provides will get optimized to the point where you can no longer tell the difference between a digital design and reality.“

I find it fascinating how accurately the AI responds to the requests made.

Danny Richman: Moreover, generative AI is still in its infancy. We are at a very, very early stage and the speed at which it is developing day by day is quite incredible. What you’re seeing at the moment is the worst version of AI there will ever be. All subsequent designs by AI will be better than what it produces at the moment. The degree of detail the AI provides will get optimized to the point where you can no longer tell the difference between a digital design and reality.

With the help of AI, you programmed FabricGenie in a mere 12 weeks, with Seb Kay handling the front design. Such a short space of time seems quite amazing; were there also real challenges along the way?

Danny Richman: The challenges didn’t really have much to do with the AI. We were well aware that the interest in FabricGenie was likely to be great in the first few weeks after the market launch because the option was new and there was nothing comparable available. One of the problems we had was the question of how we could manage highly fluctuating demand, specifically exceptional demand in a very short space of time. Processing the images takes time, as the computer can usually start processing a new image only once it has completed the one before. There are limits to how many images can be generated at one and the same time. Furthermore, FabricGenie is publicly accessible, so the question was what to do if, within a short timeframe of five seconds, for example, we got a thousand requests. How do we manage such a queue of people waiting, without them getting hugely frustrated because their requests are not being answered? The greatest technical challenge was thus not a matter of the AI, but of system management. Added to which, we knew that the system would be prone to abuse, and that’s why we had to make certain in advance that users were not able to enter vulgar requests.

How is FabricGenie financed?

Danny Richman: Well I can’t give any concrete figures, but I can explain how the relationship with The Millshop Online company functions. My roots are in software development, and for the last 20 years I’ve been working first and foremost in digital marketing and search engine optimization. The Millshop Online was a client of mine when I was working in that field. Now I like to study companies from all manner of different perspectives, look at what challenges they are facing, and identify the ones where I can be of assistance. In recent years, the AI has taken up an ever-greater portion of my working life and this is how I came to develop FabricGenie – at some point or other I had the idea of using AI-generated images to produce fabric designs and to offer this as a service in collaboration with The Millshop Online. All in all, the obstacles to realizing the project, in both financial and technical terms, were not great. I drew up a plan, and two weeks later the whole thing went into the development phase.

One of your core statements is that AI should not be regarded as something meant to replace human activity and instead that processes need to be found for AI that have to date not been initiated. Could you give us an example of where AI can help us and where at the moment there is a gap that has not been filled?

Danny Richman: To a certain extent, FabricGenie is a really good example of this, as without the AI there would not really be any opportunity to offer the public a service that enables them to create their own designs and then have them printed on fabric. The only option would otherwise have been to engage the services of a professional textile designer. The latter would then have listened to the clients’ wishes, would have developed a design idea, perhaps a proposal, even. That would then go back to the clients, who would give feedback on it, in other words an iterative process. Given the costs and the amount of time involved, this is simply out of the question for most private individuals and is usually the path adopted only for the fit-out of commercial projects. A publicly accessible service for the design of textiles has simply not existed to date. And that is just one example of all the options that artificial intelligence has to offer. In recent years I have developed with AI hundreds of applications, and in the process I have not written a single line of code myself. In view of the high costs, many of these apps would not have been realized by a design team in the customary manner. The development outlays if you can rely on AI are comparatively inexpensive.

Does the AI handle its own maintenance?

Danny Richman: I’ll give you an example: If I input into ChatGPT, “Compile the code that I need to create an app that fulfills task xyz”, then the AI will produce a whole load of codes that I can then test individually. In 99 out of a hundred cases, the codes will not function first time round. I then get back to ChatGPT and tell it that the code does not function, and the AI then generates a revised version. That’s how coding using ChatGPT works. The same process is used for maintenance of the AI.

The AI learns from feedback from its users, right?

Danny Richman: Exactly. The way in which you input a request and get a response is very similar to interacting with other people.

If I were interacting with another person, in the event of an error message the other person would probably ask whether I had tried to reboot my computer.

Danny Richman: (laughs) The AI would never do that, as I can enter the knowledge I have of the function that I want it to create at the very beginning. You can train the AI so that it “knows” how it can best work together with us.

Given all the opportunities AI offers us, one could swiftly conclude that you neither need many years’ experience as a designer nor extensive training to pursue a profession in the creative industries. It sounds a bit like the classic “I could have made that” response to art. What’s your take on this?

Danny Richman: I’d like to answer that one with a comparison. The texts that AI can create for you are already very good, and the problem of AI providing erroneous information will soon be solved, I am sure. What the AI cannot manage to do is to write something on the basis of human experience, of a lived life. You can tell ChatGPT to write a text that emulates Shakespeare’s style, but it will never attain the same level that Shakespeare himself did simply because the AI has not lived the playwright’s life. The AI does not know human experience, it has not itself ever experienced pain, love, ambition, or destruction. What it does is imitate. If a designer creates something, then everything that person has experienced in his or her life is somehow incorporated into the creative process. What the AI can, for its part, come up with is the creation of designs that are of an everyday quality, that do not require a massive amount of skill or creativity.

Would you say that the role of the designer will henceforth be more like that of a curator?

Danny Richman: Most definitely. In the creative industry, AI will soon become a creative tool just the way many designers today use image processing programs to achieve results that they would never have managed to produce without the aid of those tools. That’s exactly the way AI will be used. For instance, only a short while ago a large textile corporation contacted me because it wanted to input its database of over half a million designs into the AI in order to have a personal catalog generated for it. The idea was for their designers to then use that catalog in their work. From my perspective, that is one of the main uses we are going to see going forward: An AI model will be fed with individual data and will assist both brands and creatives in working in line with specific style guides and guidelines.

Can AI help enduringly optimize processes such as logistics or the transparency of the textile supply chain?

Danny Richman: Admittedly, I have not really concerned myself with those areas so far, but I would spontaneously say yes. I mean, it would already be useful to simply look at the proposals that ChatGPT offers if you key in, “Please suggest some ways that AI could be used to create more sustainable textile manufacturing processes.” The AI will then try, on the basis of the patterns that are hitherto prevalent, to improve the process across the board. That is the core of AI: It’s all about efficiency. Take an example: In order to optimize my nutrition, I have my physical composition, my metabolism analyzed. The data thus obtained then forms the basis for an application that I developed in less than 15 minutes: In a restaurant I take a photo of the menu that I then upload into my app. The app then evaluates it and reports back to me on which dishes would be ideal for me. In other words, AI can be useful in all walks of life.

What should the legal framework look like that we need to decide on for the future use of AI?

Danny Richman: Well, I’m not a lawyer, and I therefore can’t really say much about the legal aspects involved. My personal opinion, however, is that there are two fundamental questions involved: Do the inputted data for training the AI contravene copyright laws in any way? And what rights do we have to the AI’s output, to the results? Can I, for example, come up with a textile design using FabricGenie, produce it, and at the same time make certain that this particular design does not get copied? At the moment there is no unequivocal answer to this, as various different priorities have to be weighed up against one another. On the one hand, we want to protect the original creative work someone does; on the other, what we are looking at is an incredibly powerful technology that we should try not to restrict to an overly great extent.

In the context of a press conference at Heimtextil 2024 where you were a guest participant, you also mentioned that one conviction in developing things going forward must be that people don’t stick to the rules.

Danny Richman: Exactly. AI also offers us the potential to produce forgeries of all kinds. We’re doing this interview by videochat – and a short sequence from it would already suffice to generate a bot that can hardly be distinguished from you the person. This technology not only offers endless positive opportunities; it can also inflict considerable damage. Thankfully, there are already countless developers worldwide who are busy working to solve this problem.

What are you working on at the moment?

Danny Richman: I have the great fortune to be able first and foremost to tackle projects that have more to do with my passion and my interest in the topic than with financial aspects. At the moment I am active in the education space. For example, I’ve developed the “DarwinBot” which can help in schools to convey knowledge about Darwin’s doctrine. Children can ask the chatbot questions in order to find out more about Darwin’s thoughts and his life. As a next step, I want to connect this to VR technology, as that will give school students a digital pathway via which they can accompany Charles Darwin on his travels. By means of AI, education can thus be brought to life in a persuasive manner that really grabs kids and offers them an unforgettable experience. At the moment I can think of nothing more exciting than that.