Aug 8, 2013

Adeline Seidel: You are the brain behind the “BIX” project, a media façade for Kunsthaus Graz. A whole host of similar concepts have been realized since; they tend to oscillate between being purely media façades and celebrating the architecture by way of media systems. Does architecture necessarily rely on such technological appliances to have a voice?

Jan Edler: Originally the assignment was far less specific. Our brief was to think about ways in which media could be involved in this art space and the role they might play in this context. However, it then looked like the architectural concept by Peter Cook und Colin Fournier was to undergo massive changes: The plan was to replace the acrylic glass façade with a non-translucent material. This situation prompted the architects’ decision to use the BIX project as an argument to “save their acrylic skin”. With BIX the idea was to create a communicative membrane between the museum and the public space. Whereby it bears remembering we are anything but technology buffs. We have no special relationship with technology; we just use what happens to be available in our projects. Or, to put it simply, what “gets the job done”. That is precisely what BIX capitalizes on and it’s the essence of all the other projects that have since followed.

In creating your media façades, you don’t rely on cutting-edge technologies but instead use existing components – fluorescent tubes for example. Is your success above all a result of your creed of keeping things simple?

Jan Edler: I think there are various levels that marry to make our media façades successful. First of all, we reject the common perception of what a “media façade” should ideally be or fulfill. In other words, we do not simply apply the notion of the screen to the architecture as this would just be another version of “Bladerunner” – and absolutely devoid of meaning. Let me explain: The standards you apply to such media, for example resolution, contrast, color, orthogonality, are radically different from those you apply to the architecture. Secondly, we aspire to think our way into the architecture, as it were, and cultivate a format that is both suitable and expressive. In a sense, we aspire to animate the architecture itself. Our projects are not about playing a sequence of images, but about tailoring a bespoke program to this particular façade. Which necessarily implies that we need to engage with the architecture at hand.

And “thirdly”?

Jan Edler: Yes, indeed, thirdly, and that has to do with the ability to adapt to the latest trends. Display technologies become outdated extremely fast and, in contrast to architecture, innovation cycles are extremely short. Unless your financial budget is enormous, it’s impossible to keep up with cutting-edge innovations and adapt the building accordingly. For this reason, we were delighted to have opted for an “old” medium such as fluorescent tubes with BIX. When it comes to aging in technology, fluorescent tubes are subject to the same assessment criteria as the building itself. As a result, BIX is more like a tattoo that adorns the entire building, not a screen that is stuck onto the façade. Kunsthaus Graz is set to celebrate its 10th anniversary this September. And the façade still works – no one has ever suggested replacing the present installation with a modern LED installation.

What can architectural history reveal about media façades such as this one?

Jan Edler: Architectural history shows: Architecture took a very long time before it was able to embrace a formal idiom such as seen in the shape of Kunsthaus Graz. The same applies to programming those façades. Just because the technology is available doesn’t mean to say that we know how to handle it. First comes the learning process, the experimental stage that will manifest the actual purpose of such façades: What does a “talking” architecture communicate to us? Which language, which grammar is the correct one, how swiftly can it operate? Our job here is to take the first tentative steps.

In your opinion, what was the outcome of these first walking steps?

Jan Edler: Our first attempts at walking turned out to be rather ambivalent. In Graz we were overflowing with enthusiasm: This is the first ever communicative skin of a cultural institution, a skin that does not bow down to the pressures of commercial exploitation! Graz is a kind of long-term research project, which allows us to rely on artistic input to formulate an idiom that we are not yet aware of. Of course there were teething problems with using such a medium. But over the last ten years a number of similar, very promising artistic projects have evolved.

A good example is “Crystal Mesh”, which was designed for the “Urban Entertainment Center” in Singapore. Here the architects suggested joining forces with the various local art and design academies to embellish the façade. The idea was to give the façade to the students as an “experimental lab” as it were. Sadly, the building was sold very swiftly after that, and we never found out if these new ideas are bearing fruit. Or whether you mostly get to see the screen saver we developed to test the system’s functionality. So that was a disappointment for us.

On a high note, we are very hopeful that our “C4” project for the “Espacio de Creación Artística Contemporánea”, a media and art center with studios and exhibition spaces in Cordoba, will be a great success. The idea is that the students will use the façade as an exciting tool, and in doing so assign the building with a second personality. However, given the difficult economic situation in Andalucía at present, the building has sadly stood idle so far.

In your work, do you attach a lot of importance to the fusion of dynamic-response façade functions and moving façade animation?

Jan Edler: Even today there are buildings featuring a technology that responds to a variety of things at once. Many façades have the ability to adapt: They assimilate to the environmental conditions to which they are exposed, something that is not so obvious at first glance. Any concept that will perceive the building technology in place beyond that which is commonly considered “useful”, we regard as extremely smart. In this sense, technology not only serves to provide some kind of service to the building, but in addition it enables the structure to communicate with the outside world. Much can be achieved at relatively low cost if these two functions are married.

Are you referring to your concept for the new ECB building here?

Jan Edler: Right. The “NIX” concept sounds very simple at first: 24,000 office luminaires will be centrally controlled as soon as they are no longer needed for lighting – because the office in question is empty. These luminaires will then transform the entire building volume into a dynamic 3D sculpture. But note that the only building technology we use is that which is already in place. The project’s name “NIX” (nothing) alludes to this. Andreas Ruby once called it “architectural deep massage”.

Regrettably, this level has not been featured in the architects’ design chain, and it’s crucial that such concepts be included right from the beginning of planning. Plus the concept puts in touch different fields of planning that usually do not have all that much to do with one another. As a result, the realization of this essentially simple idea turns into a complex task.

So NIX will not be used in the new ECB building. Does this mean you have cast the concept aside?

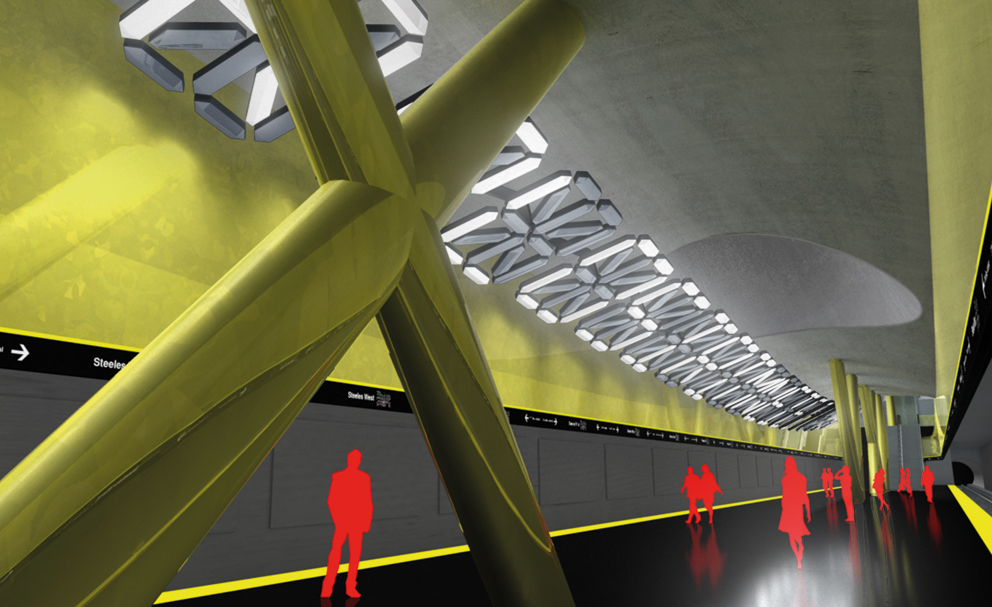

Jan Edler: No, in fact we are busy applying, albeit in pared down form, the basic NIX principle to a subway station in Toronto that is currently being planned by Will Alsop. The idea is to “hijack” the existing lighting in the station and transform it into a 16-segment display. So once again, we are not adding anything but simply expanding the complexity of what is already there. What makes this concept so special is that visitors can design the display themselves by inputting text into a keyboard. This text will then illuminate the platform immediately. The whole venture is an experiment on the issue of censorship in public places: We believe that passengers will eventually use the installation to add a touch of poetry to the station – once they have internalized that they are free to write absolutely anything they want and so will lose interest in writing messages designed to provoke fellow passengers. The odd inappropriate messages will still serve to provide the necessary light for everyone...

Media façades only work at night. So how do you get buildings to “talk” during the day?

Jan Edler: The majority of our projects can be adapted to different scenarios – and not just as regards lighting. An example is the competition for the “Deutsche Bahn” headquarters in Berlin, which we did together with Norman Forster. Here we proposed the use of a modified sunscreen. The roller blinds essentially operate like rotating billboards. The combination of color and translucency in the fabric allows you to control the volume of sunlight that is permitted inside. So by storing a set of physical properties in the sunscreen you can visibly alter a building’s color and translucency.

If all façades communicated by way of such methods as you design, what would this entail for our cities?

Jan Edler: Personally I think that this will neither happen, nor would it be useful thing to happen. And yet: Communicative ability in buildings has always been a topic of great interest among architects. The majority of façades are supposed to provide a view of the interior and take on the role of mediator between that which happens inside and that which takes place outside. In this respect all façades that reveal something about the building can be called media façades. In the past people used curtains, today we pull down blinds, which may even be automatically controlled. These aspects will change the face of a building, just like it has always been in the transition between day and night. There is no doubt that technologies will work to visibly accentuate these modifications even further. Which is not to say that each and every building will necessarily tell a story or function as a communicative medium. I am very hopeful that the world of advertising will refrain from exploring these possibilities further. There is too much interference between architecture and advertising for this to happen, which will only lead to problems. Advertising and architecture really are two different things: We all know that large urban advertising formats superimposed on the façade tend to negate the architecture beneath it!

So you disagree that advertising is the next logical step in the “utilization” of media façades…

Jan Edler: Our concepts are far too coarse to meet the requirements of these advertising formats. It might work for special formats. That said, the advertising industry is always keen to use standard formats that can be used again.

Which types of building lend themselves best to conceptual media façades like the ones you formulate?

Jan Edler: They work well for all buildings that take pride of place in the public realm. Institutions that are in the public limelight. Or those that display extraordinary architecture. Indeed, media façades can be “just” design – without any functional aspects. I think we have quite a generous range of possibilities here. Right now, we are still on the lookout for a high-rise for NIX – after all we know how it works now. Personally I am not a fan of the present trend in sculptural high-rise design. For me, purity in design such as celebrated by New York’s “Seagram Building” continues to emanate simple but superior elegance. And it shows: “Less is more” also applies to high-rises which can become iconic objects of sculptural quality.

› The adaptable house

› NO NO NO NO NO The book to go with the Seagram Building

› Glass, glass and nothing but glass

› Good illumination

› The Selfi-Façade