Sustainability

Shaping Changes

Anna Moldenhauer: What is it that spurs you on?

June Fàbregas: For one thing the fact that owing to industrialization materials have become increasingly standardized. There is now no scope left at all for variations or diversity. The complete opposite is the case in nature which offers an incredibly large number of types of wood, stones and so on. During the Covid19 pandemic we became painfully aware of how dependent we are on the resources of other countries and that they are not going to be available ad finitum. These are the factors that motivate us, not to forget that as a community we don’t have a circular approach to resources, we don’t have a long-term concept for securing what we all need, and many industrially manufactured materials fall far short in terms of aesthetics.

Freia Achenbach: We also like the idea of being able to lend a new purpose to a material that at first sight is no longer of any value.

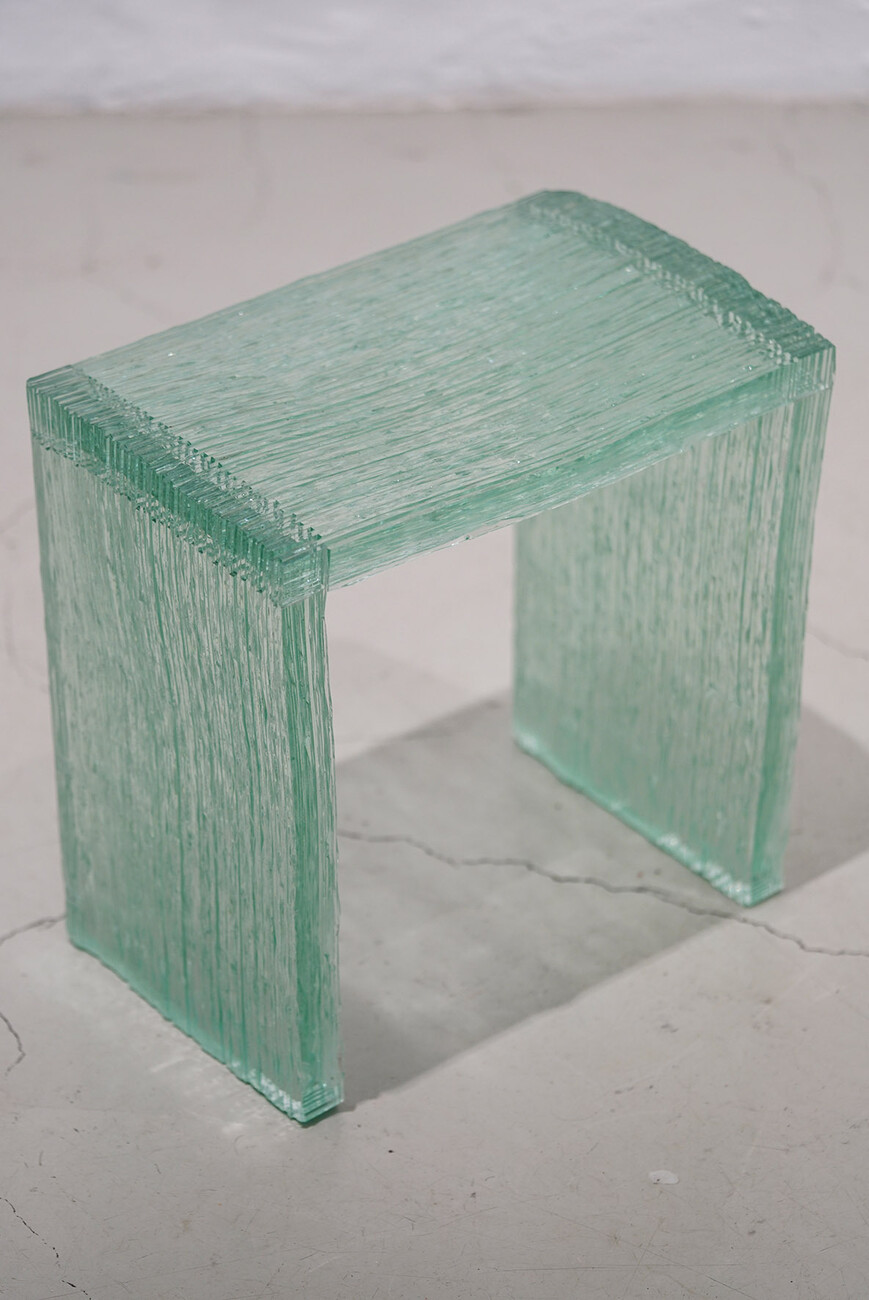

The unused resources you reanimate include mineral rocks as well as building rubble, roof tiles, remnants of glass and even disused gravestones. How can you tell that a resource might be of use to you?

Freia Achenbach: We focus heavily on which resources are available in the immediate vicinity, for example in Stuttgart, where we are based. There are a great many building sites in the city so there are large amounts of construction waste. We examine whether the material has already been recycled, and if it has, in what form. Next, we analyze what the options are for adopting a different perspective and assess whether the material is interesting for us to work with.

June Fàbregas: In addition, we try to favor natural materials that don’t contain any toxins. This is also for our own protection as we pick up the material ourselves and work with it; in other words we come into direct contact with it.

How do you get hold of the materials?

Freia Achenbach: As regards construction waste, we approach the person(s) running a building site direct and ask if we can work with their waste materials. We meanwhile also cooperate with recycling depots for our research into an alternative to cement. Now and again we are offered materials such as old roof tiles. Whether we can accept them or not also depends on whether we have enough space to store them. However, that tends to be the exception as in most cases we are the ones doing the asking.

June Fàbregas: It depends what stage of our research we’re in. We have been working a good three years on finding an alternative to concrete and things are pretty straightforward – other projects have just started and a lot comes about spontaneously.

You’ve set up a digital archive at www.city-mine.online for the material waste generated by the Stuttgart21 site. What was the idea behind that?

Freia Achenbach: Stuttgart21 is a watershed event in Stuttgart’s history. In the case of this project, we consider the waste both as a resource and as a source of information. Thanks to the archive we can reappraise the finds, they are lent a value and a platform. It’s a creative exploration of their shapes and properties, supplemented by information that re-injects meaning into the material. The archive is currently closed but we could revisit it and continue it at any time if needed.

June Fàbregas: Another approach we have is to swap ideas with other creative people, meaning the archive also serves as a source of information. Moreover, this exploration of your own surroundings emulates the archaeological voyages of discovery undertaken in past centuries. Sometimes the fascinating places where you can discover new things are right on your doorstep.

The things you produce vary a great deal, are functional, sculptural, experimental. You combine research and hands-on work. What ultimately determines the outcome?

June Fàbregas: Often the outcome is determined by our collaboration say with art institutions or researchers, which enable us to give shape to our message and strike a chord with players in industry. Our works show different stages – we want to create a vision with art; the research helps us understand how things work and to consider alternatives, while the product or functional object creates a connection to the consumers.

Freia Achenbach: When it comes down to it, the outcome often depends on the briefing or the overall conditions, such as the timeframe we have at our disposal or the topical focus, but also the statement one would like to make. Is it about demonstrating new processing options or an experimental processing technique? Is the result intended to be a product, or is the research meant to reveal what is fundamentally possible with a technology?

Some projects extend over several years. How do you finance them?

Freia Achenbach: That is not always easy. We started our research into finding an alternative to cement as part of the State Funding Program for Graduates and were allowed one year for that. There are also times when we do not receive any funding or sponsorship for our work, so we also take on other freelance jobs and essentially, we are always on the lookout for firms or institutes willing to collaborate with us. Especially when it’s a matter of realizing an idea in the field of research it’s not feasible for us as a studio to go it alone.

Have you ever been surprised when researching into a new resource that it hadn’t been used before?

June Fàbregas: That’s basically how we feel about all the resources we explore into. For example, during our research into alternatives for concrete when visiting waste dumps, we saw that marble was being mixed with tarmac or broken concrete. The fragments themselves were so diverse but the final product was just gray sand.

Freia Achenbach: Naturally, we appreciate that large-scale processes are often complicated and that it’s easier for us as a studio to develop a fresh take on something. That’s often an advantage. That said, we are often surprised about some of the ways resources are handled.

June Fàbregas: It’s also interesting how much the value of materials can change. Take salt which was once an important means of payment while today it’s a common, everyday item.

What changes need to be made to legislation in your opinion for urban mining, the exploitation of a city’s resources, to become the standard?

Freia Achenbach: In Germany, there are countless official norms and certifications that render recycling and reusing materials very complicated. Being able to use a material like construction waste on a large scale is a lengthy process. To begin with it would be helpful to offer pilot projects for testing materials.

June Fàbregas: We need to be bolder and venture the one or other experiment rather than analyzing processes for over a decade behind closed doors. By the time one project is complete we are likely to have encountered other problems that need solving. Other countries that are not as hesitant are often quicker than Germany when it comes to new developments. To give you one example: We’re in touch with a recycling firm that specializes in recycling roof tiles. The latter are purchased as waste material and shredded. There are many companies that would be interested in this resource because it can be used as fertilizer amongst other things. However, the recycling firm isn’t allowed to re-sell its product because it is classed as waste. Such trivialities often determine whether a development is successful or not.

What was your concept for the “Baked Ornament Rug”?

Freia Achenbach: The project came about in connection with GRDXKN structure printing. The latter is a textile printing technique that we’ve tested in various application areas to understand what properties a material has and how it can be processed. For example, to test slip resistance or abrasion resistance. The “Baked Ornament Rug” was created by applying the material to the textile using stencil printing so that the pattern is not produced by the highly-complex process of weaving but rather appears like a three-dimensional relief on the textile. It was simultaneously a play on the familiar image of an ornamental carpet, the translation of something familiar into a new guise.

What are you currently working on?

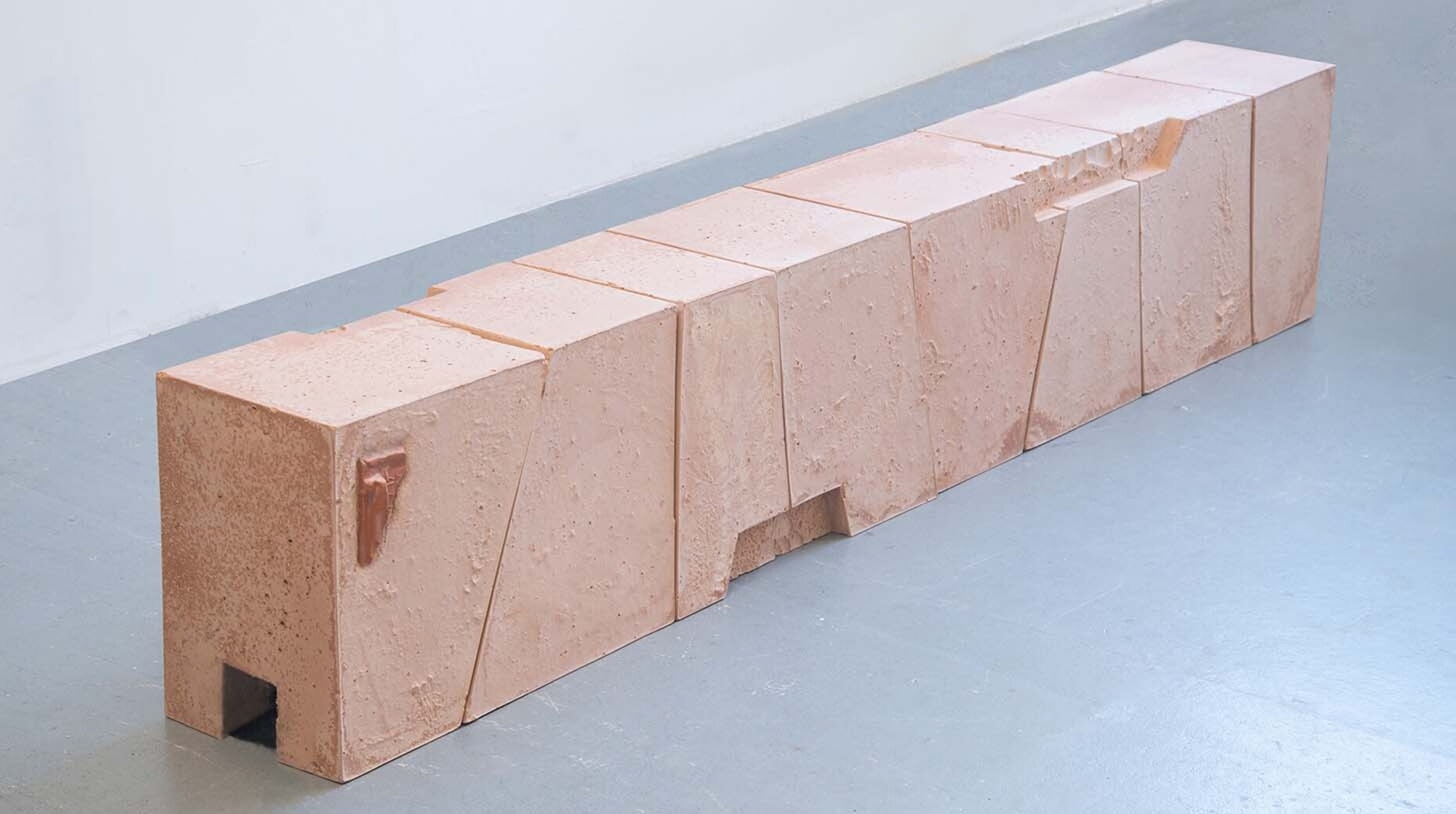

June Fàbregas: We’ve been able to continue our research on an alternative to concrete in collaboration with Stuttgart University of Applied Sciences and seek to translate our work into a product. We’re also putting the technology to other uses, for example to construct an altar from ash.

Freia Achenbach: Last year we also realized the installation “In Situ” for which we developed our own production tools. The latter allow us to process the material in a kind of circular extrusion. We’d now like to use the same technique to get to grips more with using it in contract work.

What’s the significance of your name?

Freia Achenbach: There is no deeper meaning to the name anima ona. It’s a play on words involving Catalan and German terms, in other words our respective mother languages.

June Fàbregas: The other thing is that we weren’t particularly interested in studio design. Instead we’d like to indicate that we are a studio for creative projects that is always changing and does not have a set size. Cooperating with other disciplines is important to us.