The cemetery of San Cataldo in Modena is an example of Aldo Rossi's architecture of melancholy for Diogo Seixas Lopes. Photo © Nuno Cera

Bitter beauty

|

|

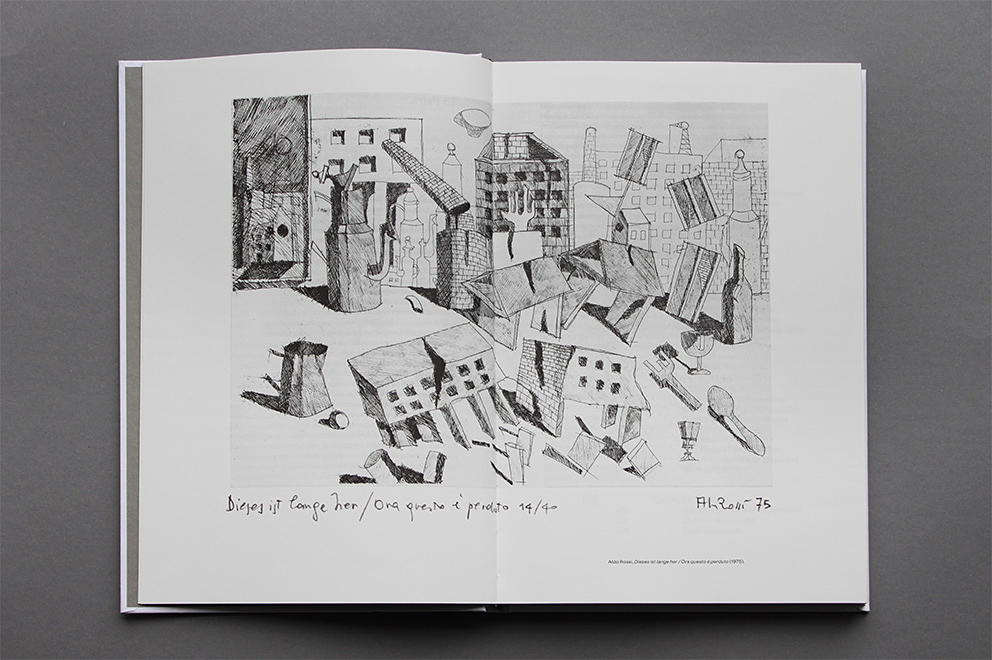

Im Gespräch: Diogo Seixas Lopes Nov 20, 2015 If one goes by what Diogo Seixas Lopes says, then many aspects of the projects and texts of Aldo Rossi (1931 to 1997) bring to mind the metaphysical gaze of a Giorgio de Chirico, the cultural skepticism of an Adolf Loos, the exalted rationalism of an Étienne-Louis Boullée, and the visual enigmas of an Albrecht Dürer. Lopes believes there are many reasons why we can discern references to gloom and crisis in Rossi’s oeuvre and should therefore see the latter as having its foundations in the concept of melancholy as the source of both suffering but also inspiration. “Melancholy is in this sense the character of Mortality,” wrote Robert Burton in his “Anatomy of Melancholy” as long ago as 1621. While the architecture mainly subscribes to the principle of the will and reason, Lopes suggests that Rossi was not content with architecture’s “deficient brief” and brought subjectivity into play as a consequence. Adeline Seidel asked Diogo Seixas Lopes how he came up with this idea and what buildings stand as evidence for it. Adeline Seidel: So how did you actually come up with the idea that Aldo Rossi’s architecture is imbued with melancholy? Diogo Lopes: The original idea for my research started about 10 years ago as a “pitch” to my doctoral supervisor, Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, at the ETH Zürich. You have to realize that doctoral studies are conducted there in a traditional format, meaning if your proposal is accepted by the supervisor you are thereafter basically on your own. This comprises certain risks, but also a lot of advantages because you enjoy a certain freedom of action deriving from the intellectual trust that ETH gives the candidate. So, my first pitch was mainly epochal. It had to do with a “sense of loss”, a disenchantment of sorts, that was felt in the early 1970s specially in Europe and America. My idea was to investigate to what point that feeling of crisis translated into architecture or not. Lampugnani was crucial to outlining the trope and leitmotif of melancholy, thus establishing a wider temporal framework for the whole research. From thereon, by focusing on the 1970s as the time-frame, it was only natural I would arrive at the subject of Aldo Rossi given his notoriety at that time. I then noticed the recurrence of the word melancholy used to label his work in numerous critical readings from the very outset. That helped to decide the “mood” and “character” of my investigation. Adeline Seidel: Can you give me an example of how and where there is a relation between melancholy and Rossi’s architecture? Diogo Lopes: The relation between melancholy and the architecture of Aldo Rossi is haphazard and instinctive, just as is the subject matter. But it is clearly a pattern among many critical readings of this work penned from the 1970s onwards. An example, for instance, would be the postscript that US architectural historian Vincent Scully wrote for the original edition of “A Scientific Autobiography”, the second book Rossi published, in 1981. There Scully mentions spaces “taut with possibility, deeply evocative of presences as yet hidden but about to step forth, grand and melancholy like tragic actors on the classic stage.” There are plenty of other cases where the word melancholy is used in the same sense. Adeline Seidel: I assume that alongside all the research you did in archives you also visited most of the buildings Rossi designed. Which of them do you feel is a good example of Rossi’s architecture of melancholy? Diogo Lopes: I would definitely answer: the Cemetery of San Cataldo in Modena. It is the prime conclusion of my book. Even incomplete, the cemetery is an extreme case of an architecture of melancholy. A monument to a contemporary version of that idea where, by definition, some rules do not apply. Despite its harsh beauty, or due to it, there is something very cruel about that place. I witnessed other visitors literally feeling unwell there. A counterpoint, and sort of “twin”, in my opinion, is the School of Fagnano Olona designed by Rossi during the same period of San Cataldo. There a spectral recollection of a lost kingdom of childhood prevails.

|

Rossi designed the cemetery San Cataldo (1971-1984) a car accident. Photo © Nuno Cera

"Even incomplete, the cemetery is an extreme case of an architecture of melancholy. A monument to a contemporary version of that idea where, by definition, some rules do not apply.", explains Lopes. Poto © Nuno Cera

Photo © Nuno Cera

The book to the research proejct. Photo © Sabrina Spee, Stylepark

|