It concerns us all

Anna Moldenhauer: Why did you decide to focus on the issue of homelessness in the form of an exhibition?

Daniel Talesnik: The exhibition "Who's next" was first shown in 2021 at the Architekturmuseum der TUM, because homelessness is an aspect that belongs thematically to the field of architecture. Homelessness exists in most cities in the world and the pandemic has increased the urgency to find solutions for it. We therefore wanted to give space to this important topic. The question we asked ourselves was also what the role of both architects and society is in this. What scenarios are there that could help?

Together with your team, you determined eight international metropolises for the research, plus ten German cities. What criteria were used to select these?

Daniel Talesnik: We decided to present the concepts of eight global cities that are not in Europe, because in these "welfare states" there is a social system, a safety net. In the USA, for example, this does not exist. The situation can become serious for people there very quickly if they lose their home due to unemployment, for example. The eight metropolises also have in common that they are characterised by prosperity and that there is a strong contrast between rich and poor in these cities. We have traced the development of the selected cities over the last 13 years. For the research, teams travelled through the cities to explore their biographies according to predefined guidelines. In this context, the fundamental understanding in our society is whether there should be a basic right to housing. Homelessness is a global problem, but it is also always local. It is thus also interesting to explore the causes, because in addition to a lack of affordable housing, climate change, for example, can lead to homelessness, as in Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Was there a concept that particularly impressed you?

Daniel Talesnik: Many concepts were impressive, such as a mixed building use for students and homeless people in Austria, which also offers workshops and a café. Another particularly interesting insight was that not every idea can be transferred 1:1 to another city. What works well in New York City, for example, does not work at all in Los Angeles. The presentation of the projects should therefore serve more as inspiration. The boundaries between social classes, such as the number of homeless people, also vary greatly from city to city. Another factor is visibility - homeless people in Tokyo are much less conspicuous than in Moscow. The fact that homelessness could be a problem at all is a foreign thought for Japanese society. The issue is thus closely linked to the respective values and attitudes of society. Who has a right to housing and who does not? Who should be helped and who does not deserve it? Moreover, it is about creating long-term solutions, not just shelter for one night. These are the questions that concern the point of view of architecture. Instead of designing dormitories for 12 people, one approach is to design smaller units that offer privacy. The particular programme determines the architecture. Sometimes the materiality is also decisive for the projects: is it about building quickly and creating flexible spaces or about architecture that stays on site? The goal is a social quality, spatially and programmatically. Another architectural dimension is the centrality of the accommodation in the city instead of outsourcing it to the periphery.

Did the teams in the cities also get to talk to homeless people?

Daniel Talesnik: Good question. Our focus was primarily on NGOs, on the community, on aid institutions, on the dimension of participation. We show 19 architectural examples and six films, but hardly any photography. We didn't want to depict misery, because we understand the architectural question more objectively than subjectively. The films bring the dimension of homelessness into the space. For each project we give the information about how much the building cost the community, how many people live in it, whether it is temporary or long-term, et cetera. That's quantitative, plus qualitative features. You can see that what matters is that the architecture meets people's needs. We can't offer a universal understanding of the complex problem of homelessness with the exhibition, but we want to find a way to talk about it with it. When you visit the show, you have to work with it, engage with it, read it, think about it. Hopefully, at the end, visitors will have a better point of view on the subject and a different understanding. The Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe is also located directly at the north exit of Hamburg's main railway station - many homeless people stay in this area every day.

I find it very interesting the wide range of topics you offer visitors. When you understand how big the problem is already in your own city, the global urgency to find solutions for it may become more tangible.

Daniel Talesnik: Yes, absolutely. One of the things we did for outreach was to create a map for each city showing the options for homeless people to get the basic necessities - like shelters, food banks or public toilets, mobile or fixed locations. When homelessness is made visible, the city is read differently.

You are an architect yourself and also teach at universities. Would you say that the topic of homelessness in urban space is sufficiently addressed in architectural education?

Daniel Talesnik: An exhibition like this hopefully also provides motivation for architecture students and teachers to engage more with the topic. Architects are not the saviours of the homeless, but part of architectural practice should be the social aspect to help improve the situation with the help of the discipline. Homelessness and the negligent handling of the issue is a problem of society as a whole and concerns us all. Hence the title of the exhibition, Who's next? Each and every one of us can be affected by homelessness in the course of our lives.

Who's next?

Homelessness, Architecture and the City

Until 12 March 2023

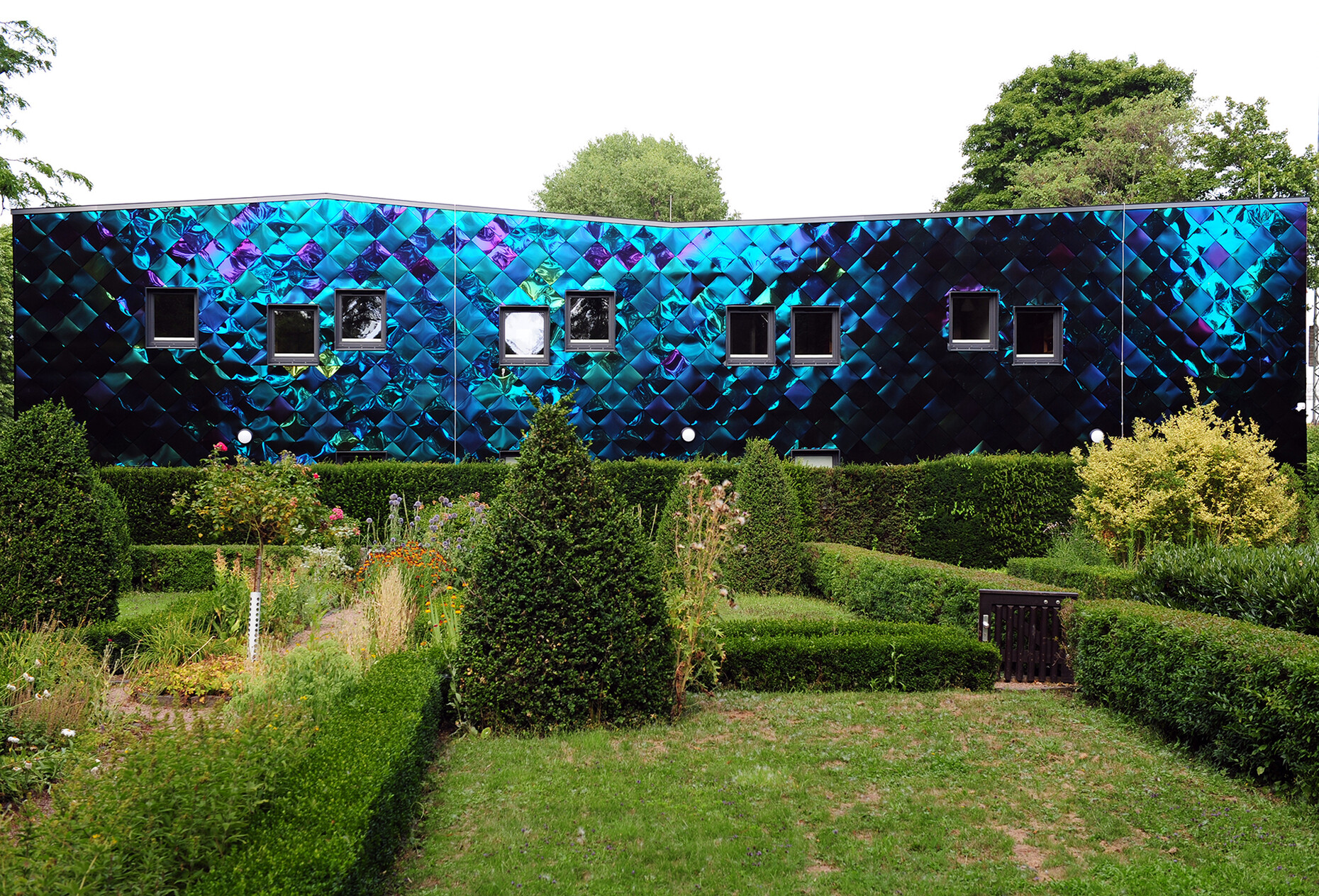

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Steintorplatz

20099 Hamburg

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Sunday: 10 am to 6 pm

Thursday: 10 am to 9 pm

Excerpt from the accompanying programme:

Alternative city tours

11 December 2022

29 January 2023

5 March 2023

3 p.m. each day, admission: 10 euros, reduced rate 5 euros

Meeting point: Main entrance of the MK&G

Without shelter – public space as living space

Workshop of the social design lab of the Hans Sauer Foundation in cooperation with the design studio criticalform and the MK&G.

Design potentials and the failure of social design processes in relation to homelessness

Tip: The Hamburg street magazine Hinz&Kunzt is showing a parallel photo series on homelessness in Tokyo by Ulrike Myrzik and Manfred Jarisch at Hinz&Kunzt-Haus, Minenstraße 9, 20099 Hamburg.

Whos's Next?

Homelessness, architecture and the city

Published by Daniel Talesnik and Andreas Lepik

ArchiTangle Publishing House

48 Euro (in the museum 39,90 Euro)