STYLEPARK ZUMTOBEL

High Performer

When Zumtobel first approached the Gensler design and architecture office about developing the sixth generation of the luminaire “Mildes Licht”, Los Angeles-based product designer Daniel Stromborg was thrilled. “Mildes Licht” numbers among the classics in office luminaires and once revolutionized the market with a completely new kind of lighting concept. Since then it has continually evolved over six generations, and was most recently advanced by James Irvine. In other words, Stromborg’s team at Gensler had to follow in big footsteps. Daniel Stromborg talks to Katharina Sommer about why the luminaire fascinates him and how exploring light inspired him to come up with new ideas.

Katharina Sommer: The first generation of the luminaire “Mildes Licht” was developed by Zumtobel in the late 1980s. What made it so special in your eyes?

Daniel Stromborg: To my mind, it was the two different types of light it offered: a focused light and a gentle ambient light from the wings, which Zumtobel described as “Mildes Licht” – mellow light. The idea of moving away from having a bright light over your desk and having an alternative of two different light zones was revolutionary and remains so to this day. People simply hadn’t seen anything like that before, especially not as a recessed version.

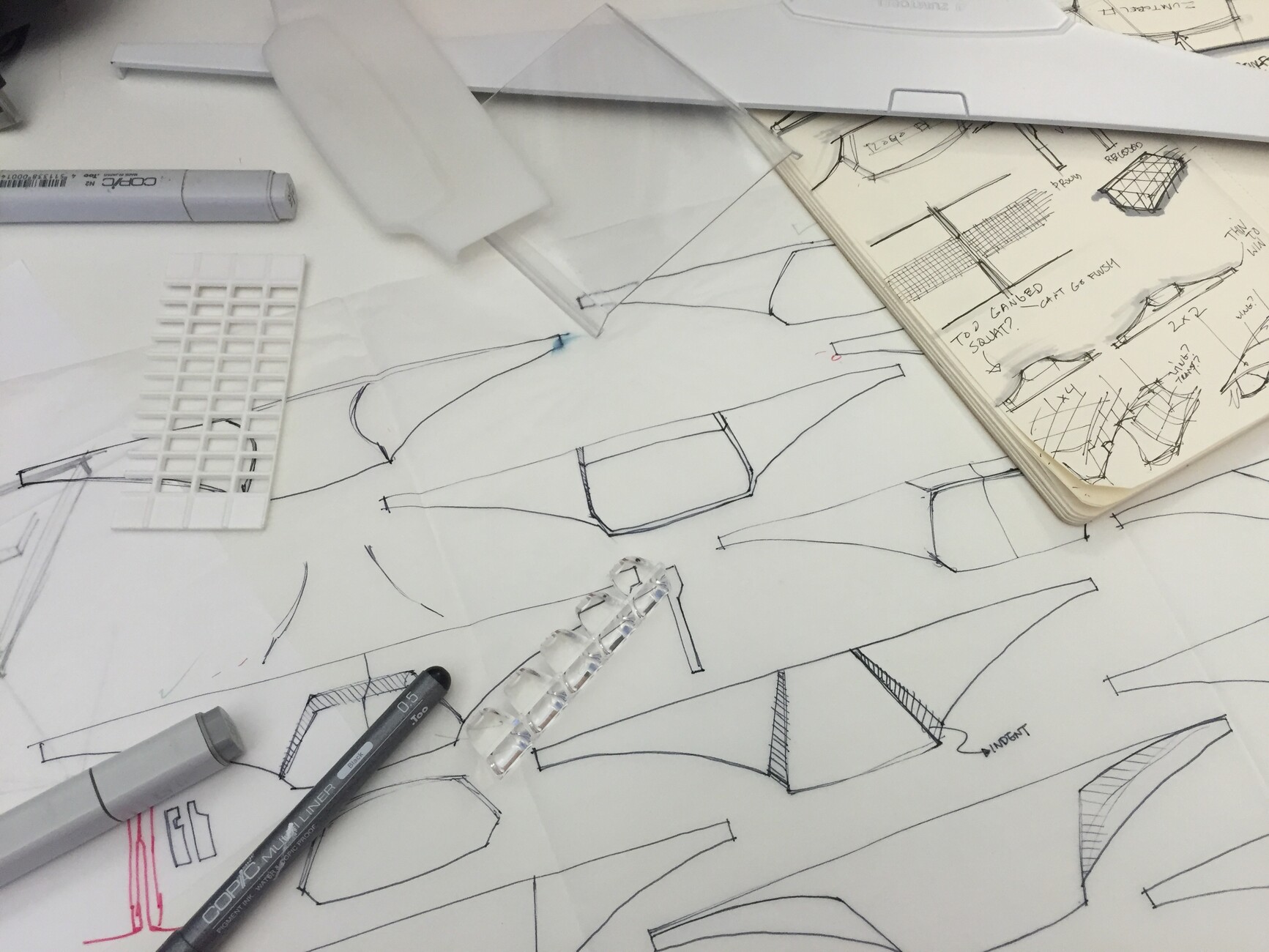

You’ve now conceived the design for the sixth generation. How did you approach the task?

Daniel Stromborg: Over the last two generations, namely generations four and five, the luminaire underwent an enormous change as a result of technological advances. For me, there is a big difference between designing from the ground up and redesigning an icon. The question we continually asked ourselves was: What do we keep and what do we reject?

A good example of an iconic design that follows this approach is the Porsche 911, which first hit the roads in 1963 and is still in production. Even if you not a student of car design, or design in general, you can tell that both the original and present-day version stem from the same kernel. Although the technology and demands have changed, there is a strong visible connection some 53 years later, which all goes to show that an object can evolve yet retain its original character. Much like the evolution of the 911, I wanted to reference the iconic characteristics “Mildes Licht” has had down through the years, especially the last two generations, and in doing so, juxtapose tradition and change.

Is there a detail you particularly like about the new “Mildes Licht”?

Daniel Stromborg: May I name two? The first is the crystalline look of our primary optic, which was a significant technological challenge for us. It took the team about 18 months to develop the means to do that. If you look at the luminaire up close, the crystal-clear lenses resemble small jewels. This is a reference to “Mildes Licht 4” (ML4), whose design is still immensely popular, but it’s also an evolution of the traditional lighting baffle. Another thing about ML4 that was perhaps lost in the fifth generation of the luminaire “Mildes Licht” was the idea that the light had a spatial presence due to a dominant middle section that visibly separates itself from the wings. Our design is also a response to today’s energy-saving regulations. For example, if there is enough daylight, then lights must be switched off in some areas. In other words, we are looking at an office in which the lights are ‘on’ over here and ‘off’ over there, which gives the ceiling a mottled look. You can’t tell which lights are broken as opposed to simply turned off. With the crystal optic on the “ML6”, it is more difficult to detect whether it is switched on or off. This gives the ceiling a uniform appearance overall, which is an interesting aspect not only for designers and architects, but also for our clients.

The second detail I particularly like is the one we call the “Irvine Step”. James Irvine designed “ML5”, and it was a tremendous honor for me to advance his work into a new luminaire. Irvine inserted a small step between the wing and the actual light source, which we most definitely wanted to retain as an homage.

Gensler focuses very intensely on the topic of workplace design. What developments are you seeing in this area?

Daniel Stromborg: Gensler periodically releases our Workplace Survey research, which examines how and where we work today and, ultimately, seeks to show what influence our environment has on us and our performance. With regard to the large, innovative companies, we know that employees must be able to choose between different work spaces—from dedicated desks to soft seating to café style settings. Many of the aspects relevant today really originate in Robert Probst and George Nelson’s “Action Office 1” produced by Hermann Miller back in 1964. Over time, there was a shift driven by the economics of space and the ideas laid out by Action Office gave way to the “cubicle farms” of “Action Office 2”. In other words, a product was transformed into its antithesis. Subsequently, there was a swing back to a more open office landscape and we are now seeing the resultant pushback on this style of space planning. While we don’t want to sit in cubicles any longer, we have realized that we need some level of privacy. In today’s open office, the most often cited workplace issue is noise, be it visual or auditory, that distracts us and disrupts our concentration. In other words, we need different zones dedicated either to focused work or to collaboration. In fact, we are developing a desking solution that addresses this and hope to see it launch next year.

In the 1980s the office landscape was altered when computers entered the workplace. The development of the first generation of the luminaire “Mildes Licht” was a reaction to these new conditions. How exactly does “ML6” respond to the current changes in workplace design?

Daniel Stromborg: At the end of the day, the luminaire “Mildes Licht” is an object. I like to think that it is an attractive luminaire, without being decorative. It was never intended to become the “It-object” in the room due to the sheer volume with which it appears in a given space. It should work with the architecture, not distract from it. I love “It-objects” like some of the work of Patricia Urquiola or Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec, but some design needs to be quiet and let performance take over.

I think part of the value proposition of this product lies in the aspect known as “activity-based lighting”. Put differently, the new “ML6” means we can optimally use new technologies, such as the ‘Ativo’ sensor. The latter discerns where we are working and if necessary then activates the luminaire’s central section. For example, throughout the course of a day, the color temperature of the light changes from warm to cold and back to warm again. We are seeing a huge push into addressing human-centric design and integrating those types of technology that can link us back to the natural world, which we would otherwise miss at our desks. After all, daylight greatly influences our well-being and health. If you want to create a workplace that best promotes employee health and focuses on the individual, then “ML6” offers you the right functions – thanks to “tunableWhite”.

Until now you have largely been involved in designing furniture and some consumer electronics. What was it like designing a luminaire for the first time?

Daniel Stromborg: It was much more interesting than I would have imagined. I had an awareness of lighting design from Ingo Maurer, for instance, who advanced experimental lighting, and of designers like Achille Castiglioni who tended to create more sculptural lit objects. But until this project came along I had never really thought about performance space lighting. So it was a stepping stone for me personally.

Has your work with light inspired you with new ideas?

Daniel Stromborg: What fascinates me is that you see versions of the luminaire “Mildes Licht” everywhere in urban areas. Recently, for example, I was in London walking along the Thames from the London Eye toward the Tower, and I passed dozens of office buildings. In just about every one of these buildings I could see at least a few floors that had previous generations of “Mildes Licht” or copies of it. I think the market for recessed and surface-mounted luminaires still offers so much potential. From a trending standpoint, some areas of interior design such as those for our media or technology clients, we have seen a shift away from this style of ceiling installation. These clients no longer lowered ceilings, but rather more open style ceilings such as we see in loft spaces. So the question is how we can take a product like “Mildes Licht” with its combination of two lighting scenarios—soft ambient light and direct light—and develop it so it can be integrated into these types of spaces. You would need some kind of suspended luminaire in that situation, which might be a path we could explore together.

That sounds as if your work is not yet finished, but just getting started.

Daniel Stromborg: Actually, I am already collaborating with Zumtobel on a new project, but it’s confidential at the moment. Zumtobel is a dream client with very committed and intelligent people from the engineers to the project managers. No one ever said the word “no” without a very well-researched answer to explain why. I really appreciate that, because I don’t like the word “no.”