SUSTAINABILITY

Radical Recycling

Yes, they really are! The skylights in the pyramid-shaped roof of this Belgian house don't just look like it, they are actually canopies that once covered the cockpits of Dutch fighter planes. And the monumental Gothic portico that now spans the driveway to another single-family house is not a kitschy fake from the local DIY store, but was salvaged during the demolition of a historic church. The ornate bay window, which does not match the architectural style or scale of a third Belgian house, was also taken from another building. Our eyes are now so accustomed to perfectly realistic Photoshop montages, that when we see such pictures we automatically ask ourselves whether they're real or whether we've succumbed to the work of a particularly clever computer artist. But no, in this case these buildings are real. And they're just three examples of the wondrous work of the exceptional Belgian architect and entrepreneur Marcel Raymaekers, whose pioneering achievements in the radical recycling of architecture are only just being discovered.

For most of his life, the now 91-year-old Raymaekers was considered both an outsider and a prodigy. He was born in a small village near Leuwen, where the Flemish landscape is at its flattest and least exciting. His parents ran the local cinema, his aunt the grocery store. His maths teacher discovered that the boy had a special awareness of space and persuaded his family to let him study architecture. In 1950, the 17-year-old enrolled at the Sint-Lucas School in Schaarbeek, a suburb of Brussels. He was the first member of his family to go to university, but he only stayed at the school for a year because he disliked the programme, which was led by Catholic monks and in which he had to repeatedly draw buildings in historical styles. He left the university without a degree and never actually got one afterwards. As a result, he was not officially allowed to work as an architect. This fact, however, didn't stop him from designing buildings for 50 years and constructing over 100 of them.

Revival at the salvage yard

He got his first commissions from relatives and acquaintances. Raymaekers also designed a house for himself and his new wife Rita. These first buildings were still quite inconspicuous, with gabled roofs and brick chimneys, combining a gentle modernism with the elements that homes in that region customarily had. Raymaekers himself later described these houses as "completely insignificant". He was dissatisfied because he found the results of his own designs to be as bland as all the small new houses surrounding him, which was precisely the mediocrity that he wanted nothing to do with. But then something occurred that completely changed his way of doing things: In the late 1950s he came across a demolition company's salvage yard in Brussels, where he bought an attic staircase that he incorporate into one of his own designs. This brought him into contact with the "demolition scene" in Flanders, where business was booming at the time. During Belgium's post-war boom, historic buildings were being demolished everywhere to make way for new construction. The land was being “ploughed up” in the truest sense of the word. Raymaekers began to visit demolition sites to pick up materials and elements. At the same time, he studied art and then become an art teacher, which, he says, gave him a new appreciation of the material he was collecting as well as a more sculptural approach to it.

Working as an art teacher allowed Raymaekers to pay the bills, while at the same time he engaged in an increasingly wild and rampant trade in used building elements. He always offered to help design and find uses for the parts his customers bought from him. In his designs from the 1960s and 1970s, the development of Raymaeker's idiosyncratic style is plain to see. In the beginning, he would inconspicuously insert one or more of the artefacts from his second-hand shop into houses that were still slightly modern. And because he also had a good relationship with a shipyard, he often used parts from old ships such as heavy planks or metal panels, adding heavy quarry stones he had picked up as well as ornate doors, wrought-iron fences and window grates.

Cockpit domes and ship planks

With time, he slowly became more courageous, and his building approach changed greatly. In a lorry, he and his friends drove around the country in search of demolition materials, which they then put in the vehicle and took with them. They got a great deal of it for free, as the demolition companies were happy to be rid of the stuff. Raymaekers collected the materials they found at an abandoned farm near Diepenbeek. This is also where he took his customers there to show them wood, natural stone slabs and windows from the Belle Epoque, as well as Gothic, neo-Gothic and Baroque archways and statues he'd gotten from demolished churches. He eloquently encouraged visitors to have such spoils installed in the homes they were planning as special luxury items.

This was the beginning of his most productive period, during which he worked with the architect Jos Witters and sculptor Raf Verjans while building many houses. Raymaekers did not have his own archive. He was far too busy visiting construction sites and lending a hand himself, whether demolishing or building. One of the early highlights of his work was the aforementioned Kelchtermans House in 1970, which consists of three pyramids designed by Witters and made from reused ship timbers clad with used roof tiles. Raymaekers used 23 cockpit canopies from scrapped Lockheed fighter planes as skylights that he had rescued from a recycling centre. Inside, tarred black ship planks, marble floors and reused windows abruptly collide with one another. The entire house is as improvised as it is opulent and imaginative, the rooms and materials a constant source of surprise. It was representative of of the increasing confidence Raymaekers felt regarding the buildings he was creating at the time.

Queen of the South

Another big step followed in 1972. Raymaekers had long been dissatisfied with the remote farmstead where he stored the salvage materials he'd collected. With the help of a wealthy customer, he bought a 15,000 square-metre property on a busy motorway between the cities of Hasselt and Genk. In a prominent location along the road he placed an illuminated crown on top of eight-metre-high, neo-Gothic cast-iron pillars. It advertised bouwantiek (building antiques) and woonkultus (domestic culture), and offered estetische raadgeving (aesthetic consultation). He used the site's existing structures to construct a sprawling building complex that served as his home, a showroom for his recycled architecture, a lavishly mirrored bar, an office and a restaurant for business lunches. There were even living quarters for his employees. Materials and elements were stored in the open space between the buildings, and here and there he constructed ad-hoc sheds from the materials, reminiscent of Kurt Schwitters' Merzbau. The site's grand entrance leads through a neo-Gothic stone gate from a church in Spa, guarded by two large stone lions who had previously guarded the railway station in Ottignie. He placed the starboard panel of a decommissioned paddle steamer he'd found somewhere on the main building's entrance façade. The name of the ship, which now became the name of the utterly amazing structure, is written there in large letters: Queen of the South. You just have to know how to make use of what you have!

Raymaekers thus had the logistical strength as well as the aesthetic and entrepreneurial self-confidence to embark on his most productive phase. He produced one fantastic house after another. House Olaerts is a sleek modern brick cuboid with large, ornate natural stone window elements on all the façades, giving each side of the house a completely different look. Inside, large wooden beamed ceilings, richly decorated carpets, a sculptural fireplace made from parts of an old ship's hull and two neo-Gothic stone portals leading to the bathrooms are surprising, to say the least. He added parts of Gustave Eiffel's Swiss summer house to the interior of House D in Izegem, but combined them with rather pompous marble, ornate stucco ceilings and placed a free-standing marble bathtub with a golden tap in the bedroom, which would have been more in keeping with Louis XIV than a single-family house in West Flanders.

House Boncher in Glabbeek is essentially the combination of the remnants of a barracks in Vervier with those of a slaughterhouse in Tienen. For a florist's in the small town of Steenokkerzeel, Raymaekers reused the Art Nouveau façade of a narrow townhouse that had to make way for Antwerp's urban motorway. Raymaekers cut the individual parts of this façade completely apart, however, and reassembled them into a brand new image for the florist's – he was never interested in historically accurate copies. With the Rubensexclusief, a love hotel in the middle of the Brabant countryside, he created a particularly frivolous work in which the pompous lust of his designs with marble floors, stucco ceilings, chandeliers and heavy velvet curtains meets tarred wood and dark metal panels. It's a kitschy, wild mixture of Versailles, Neuschwanstein and Salvador Dalí, an interior design roller coaster ride, and anyone who doesn't have to laugh when a secret passage to the bar opens up behind a reused confessional available for guests caught in flagrante delicto has little sense of humour. It's this mercilessly exuberant wit and inventiveness, always on the edge of being totally over-the-top, that characterises Raymaekers' architecture, much of which was only made it possible in the first place by a disregard of all kinds of building regulations.

Bankruptcy and discovery

Marcel Raymaekers continued to work and live in the Queen of South for over 40 years. His work was never recognised; it was neither published nor exhibited. Occasionally there were amusing articles in the local newspapers. In 2014 Raymaekers had to file for bankruptcy following a conviction for tax evasion. A building contractor took over the business and still runs it today, but he continues to let Raymaekers live there, as a tenant in his own building. And this is where Raymaekers was discovered by the young Belgian architects' collective Rotor, who came to Queen of the South in 2011 in search of used components. Over the past 10 years, Rotor have built a reputation for themselves as architectural rebels who advocate a radical approach to remodelling and reuse. In Raymaekers they discovered a kindred spirit who had been in the same business for over 50 years, without the architectural community ever taking any notice of him.

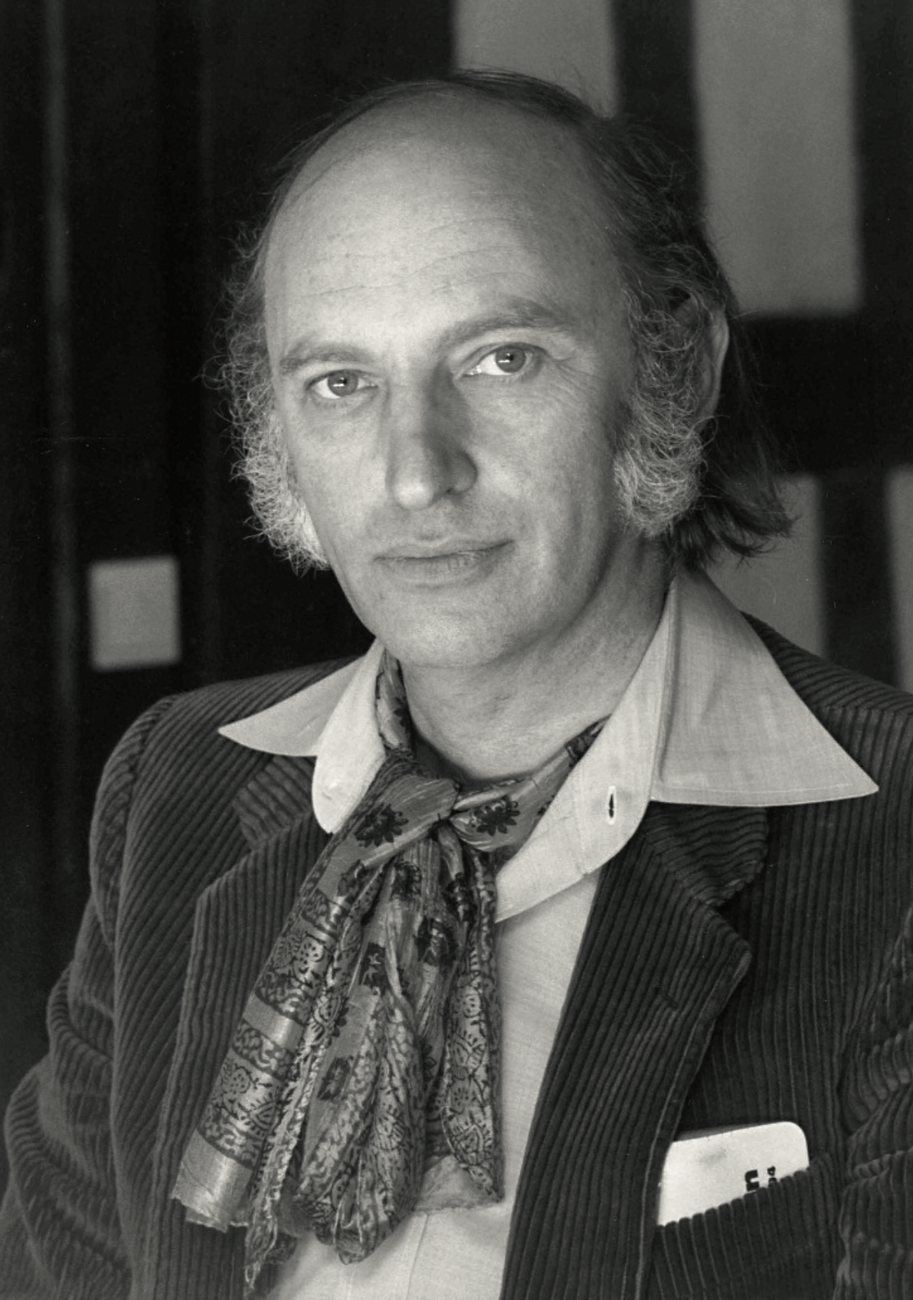

It's very lucky for us that Rotor found him! With funding from the Belgian government, they tracked down and re-documented all of the Raymaekers' buildings they were able to find. The result is a book with the marvellous title Ad Hoc Baroque, which is full of artful texts and incredible photos of endlessly imaginative architecture, the likes of which has never been seen before. And the fact that Marcel Raymaekers himself, with his self-assured appearance, balding head and thick sideburns, looks strikingly similar to the butler Riff Raff from the cult film The Rocky Horror Picture Show is just the icing on the cake.

Ad Hoc Baroque. Marcel Raymaekers' Salvage Architecture in Postwar Belgium

English, Brussels 2023

196 pages

45 Euro self-published by Rotor