Behind the scenes of Modernism

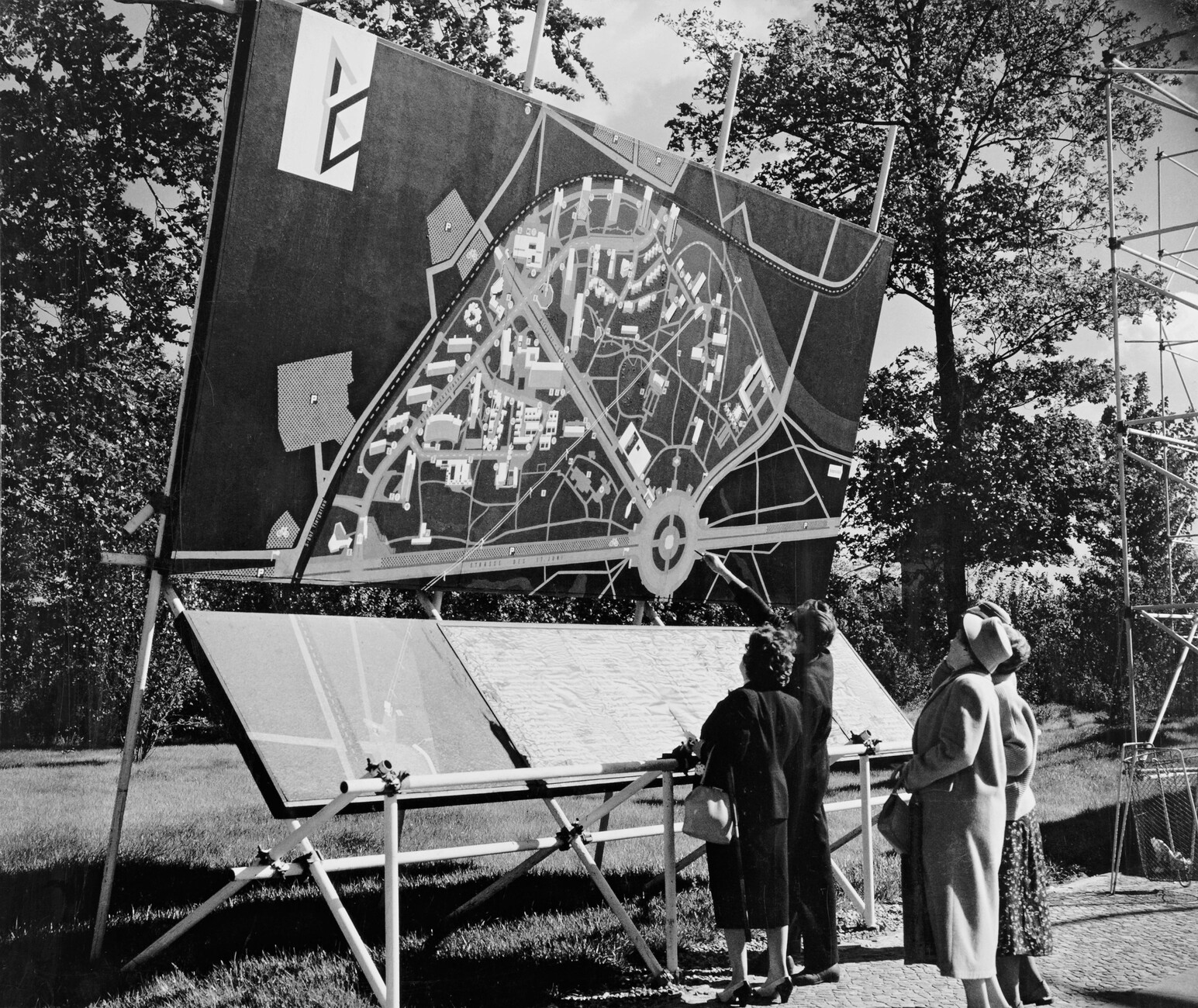

Anyone entering the Akademie der Künste in Berlin will hardly be able to overlook Otto Bartning (1883-1959) anyway. Not that anyone notices: The central, curved road leading from Hansaplatz right through Hansaviertel to S-Bahnhof Bellevue will be walking down Bartningallee. The name was chosen in enduring recognition of Bartning’s central role in the planning for the Interbau 1957, as he certainly did not design a building anywhere round here. That is something he diplomatically left to his far more famous colleagues, for whom he created a clear urban planning framework, however. It is tellingly symbolic that “his” road as the basis for the development leads past buildings designed by the likes of Oscar Niemeyer, Egon Eiermann or van den Broek and Bakema. Bartning was the hidden driver behind things; and also the one who set the task and decided the fundamentals.

So how to create an exhibition on such a person? The Akademie der Künste is just organizing a major exhibition in Werner Düttman’s Akademie building on Hanseatenweg. Directly in front of its poignant pebble-dash facade large yellow banners advertise the show with the tempting title: “Otto Bartning. Architect of Social Modernism”. Yet we can probably with some justification doubt that the exhibition will bring crowds flocking. It is simply too difficult to exhibit all the things they intend to: because alongside Bartning’s theoretical works the exhibition also wants to present how his influence decisively contributed to a trend in interwar construction that was more social and more adequately reflected human needs, and in particular how after the end of World War I and until well into the reconstruction period after World War II he acted as the eminence grise behind the wings who spun the web for new German architecture and urban planning.

Diplomat or smooth operator

Bartning was a member of dozens of associations and artists’ groups. As early as 1908 he joined Deutscher Werkbund, in 1918 was co-founder of Arbeitsrat für Kunst and from 1924 onwards is along with Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Hugo Häring and Hans Scharoun a member of the “Zehnerring”, later simply termed the “Ring”, which championed New Building in all its different versions. Bartning was consistently in the midst of debates and discussed things with almost all his important contemporaries: Bruno and Max Taut, Hermann Muthesius, Wassili and Hans Luckhardt, and Erich Mendelsohn, or artists such as Ludwig Meiner and Max Pechstein, and initially also with Otto March or his mentor at university, Paul Schultze-Naumburg; only the latter’s later fascist radicalization was to drive a wedge between them. Thus it was that Bartning, who never left Germany for any lengthier period, starting with the Reich through the interwar years and the Third Reich through to the days of West Germany, forever championed a new, contemporary modern and people-friendly architectural idiom. At the same time, his was a relatively low-key attitude, and he had a reputation as a pragmatic, moderate Modernist, something that enabled him, for all the immense political change during his life time, to remain in Germany throughout – and even be able to work. Bartning was good at getting his ideas across, one could say, or he was adept at serving many masters.

Particularly noteworthy in this context is the episode relating to the Bauhaus in Weimar. Bartning was indirectly involved in its foundation because as early as 1918 he had outlined to the Teaching Committee of Arbeitsrat für Kunst how architectural training should be fundamentally reformed. He discussed this with colleagues, including Walter Gropius (correspondence on this has survived) and thus in 1919 key ideas Bartning had floated crop up in Gropius’ Founding Manifesto for the Bauhaus in Weimar – albeit without any reference to Bartning. Many years later, Bartning wrote that it had been “deeply painful” that he had not been involved in the Bauhaus’ foundation. This did not cause a complete break, however, either with the Bauhaus or with Gropius, with whom he remained in regular contact. Either Bartning’s pain was not so large after all, or the diplomat in him gained the upper hand.

Be it deliberately or not, Bartning gained a reputation as someone everybody could agree with. Thus, in 1926 that National Conservative State Government of Thuringia that had just driven Gropius and his Bauhaus out of Weimar, appointed him director of the subsequent “Staatliche Bauhochschule”. Without making common cause with the government in question’s political agenda, Bartning was able to refer to the central Bauhaus ideas, which had after all been his. At the same time, he continued to be held in high esteem by his colleagues: Oskar Schlemmer wrote in a letter to Otto Meyer, that the “actual father of the Bauhaus idea” had now been appointed to the position in Weimar. Bartning managed with his resolute, unobtrusive integrity to gain the recognition of the protagonists of the progressive avant-garde while also not triggering too much resistance among the fascist as they gradually took power. However, four years later he had to pass the directorship in Weimar over to Paul Schultze-Naumburg, a dye-in-the-wool fascist who immediately had Oskar Schlemmer interior designs torn down and destroyed.

The church architect

One reason for Bartning’s special role, and it is one that is hard to define, was perhaps his commitment to the Church, which, albeit by chance, started at an early date. While still a student he had thanks to an old school friend who had become a vicar, been commissioned to design a church building. The parish was part of the movement that sought to sever ties to Rome and to gain its independence in protest against the Catholic Church – it therefore wanted its new buildings to reflect the Reformationist outlook. The job presumably drew Bartning’s attention to ideas on Reform church buildings and he started to concern himself with the new approach to church architecture, the changes required by the liturgy and parish life in terms of a programmatic, new typology, an interest that was to remain with him for decades. For he swiftly received other jobs for churches and parish buildings in Austria and Bohemia, as well as for country houses and villas. Bartning did not graduate, and instead before World War I, not even 30, he had already designed 14 churches.

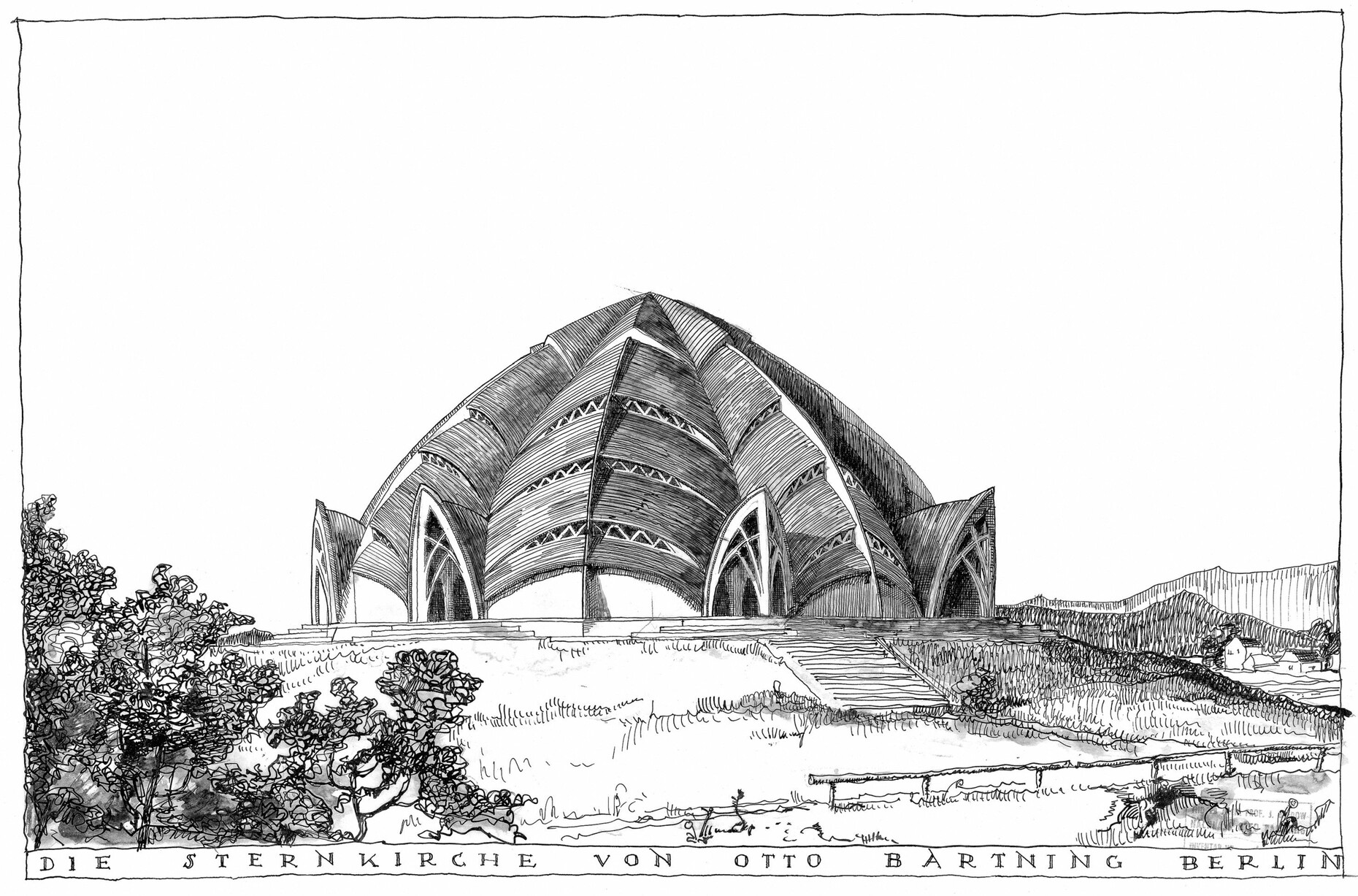

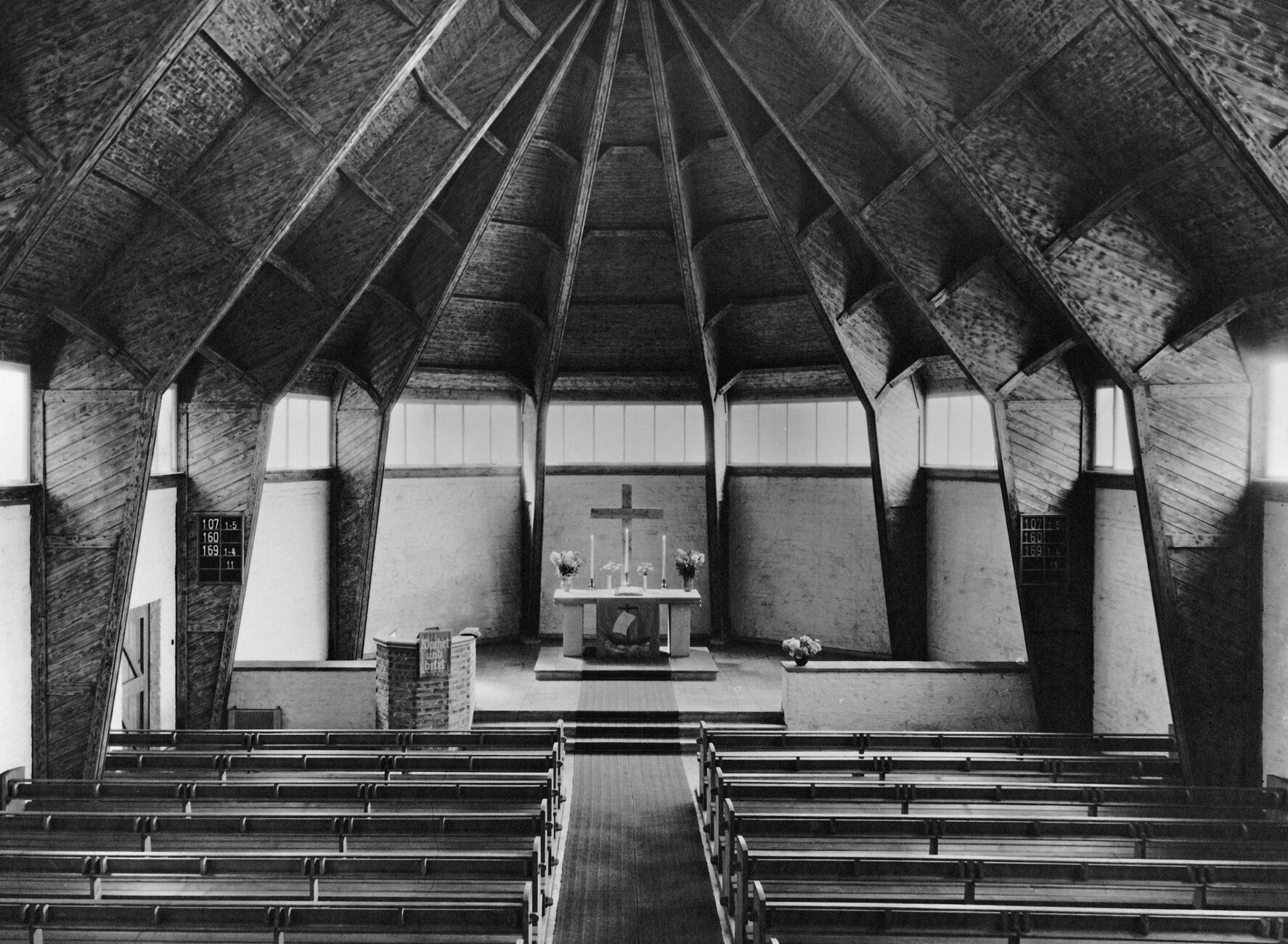

He was exempted from military service and during the war years wrote his fundamental treatise “Vom neuen Kirchenbau”; after the end of the war he applied these theoretical principles on church architecture in the most famous of his church designs. In 1922, influenced in part by the Expressionism of the “Glass Chain”, he built a model for his spectacular “Sternkirche”, which was never built, following it up between 1928 and 1934 with three prototypical church buildings: the “Stahlkirche” for the Pressa exhibition in Cologne, a circular church (the Church of the Resurrection in Essen) and a fan-shaped church (the Gustav-Adolf Church in Berlin). Together the four designs captured his programmatic considerations on the use of new materials and his development of new church ground plans; they strongly influenced many of Protestant and Reform Church buildings to come. Alongside these pioneering designs he also produced various proposals for the Protestant Church. In particular after the end of his period as director in Weimar he was able to focus fully on this work, and by 1945 had realized churches and parish buildings in Karlsruhe and Görlitz, in Lisbon (Portugal), Heerlen (Netherlands), Barcelona (Spain) and Beirut (Lebanon). With his reputation as a moderate Modernist and church architect he was able to continue running his office in the capital city of what was now the Third Reich until 1942. It was only then, after his Berlin studio had fallen prey to an Allied bombing raid and his son Peter had died in combat, that the family moved to Neckarsteinach near Heidelberg, where Bartning spent the last years of the war working on the revitalization and conversion of the Church of the Holy Spirit.

It remains unclear why he stayed in Germany and he and his family found some modus vivendi with the Nazis. He seems never to have joined the Nazi Party, he withdrew from various associations when the Nazis took them over, but remained in others. There is no record of his having supported people persecuted by the Nazis or forced into exile. He turned down a pre-War invitation to Argentina, and with terse wording after the war he described how he had “wanted to survive things here, resisting in silence”. At any rate, he made sure his good network survived the war, and was soon made President of Bund Deutscher Architekten, Deputy Chairman of the Werkbund, was a founding member of the Architecture section at the Akademie der Künste and in 1954 appointed Urban Planning Adviser to West Berlin and, in 1957, Director of the Interbau. It is astonishing how Otto Bartning preserved a sterling reputation irrespective of all the upheaval going on around him, and maintained a standing as a moderately progressive and also evidently very diplomatic strategist, one who certainly did not lean too far out of the window for his convictions. After the war he embarked on the last stage of his work as a church architect: for the Emergency Churches Program launched by the Protestant Church he developed four types of easy-to-build church structures that parishes could largely build themselves. Most of the parts of the interior, such as the gallery, the seating, the windows and doors could be prefabricated using a module grid system. By 1953, over 100 churches were built to Bartning’s plans in all four of Germany’s occupation zones.

The exhibition catalog offers a logical account of this highly diverse biography, whereas on the upper floor of the Academy building the problems of describing it as an exhibition soon become apparent. Things start with a lot of flatware on broad tables and display panels: drawings, diaries, writings, photos and correspondence bring together Bartning’s theoretical ideas and his network in the early years. And while in the rear, last section of the show there’s a large model of the Interbau and a slide show on it, the central exhibition section succumbs to the temptation of concentrating on the church buildings that are the eye-catcher in the hall (in the form of large models newly built by students from Darmstadt’s Technical University) – flanked by a few beautiful Expressionist drawings by Hans Scharoun and Wassili Luckhardt, for example.

What the title promises, namely Bartning as the “Architect of Social Modernism”, is actually only redeemed in one corner, where his interwar designs for modern buildings for healthcare are to be seen: two hospitals in Berlin, a music college hostel in Frankfurt/Oder and the long curved line of housing in Siemensstadt, destined to act as the structuring spine of the estate, are all presented here – with a few drawings. It is almost as though the organizers want to conceal these exhibits, especially as the designs are not comparable with the quality and imagination of his church buildings. Infact, it is fair to say that as an architect of social Modernism Bartning was one of many, even if at the “Reichsforschungsanstalt für Wirtschaftlichkeit im Bau- und Wohnungswesen” he contributed much to the economic typologies, standardization and rationalization of New Building.

Architect in a torn century

The exhibition only partly does justice to its title. Which fortunately does not really matter. Exploring Otto Bartning’s varied life and work remains exciting and interesting even without this connotation, perhaps more a product of the zeitgeist at present. And the exhibition and catalog provide a wealth of newly found materials compiled for the first time that can make such a closer study possible – and make visiting the exhibition and reading the book well worth-while, and not just given the major jubilees this year to which Bartning’s oeuvre contributed. Because a stronger focus on his progressive church architecture would have enabled the exhibition to contribute successfully to the celebrations surrounding the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, while a stronger emphasis on Bartning’s role at the Interbau could have been a central part of the 60th anniversary of the Hansaviertel in the summer. As it is, there’s a bit of both, and the exhibition vacillates between the categories, perhaps unintentionally in this regard emulating its own protagonist, who made certain he never erally got pigeonholed.

Ausstellung:

Otto Bartning. Architect of social Modernism

Akademie der Künste

Hanseatenweg 10

10557 Berlin

Until June 18, 2017

Catalog (in German)

Otto Bartning. Architekt einer sozialen Moderne

Eds. Akademie der Künste and Wüstenrot-Stiftung

128 pages, 280 ills., hardback.,

Justus von Liebig Verlag, Darmstadt 2017

ISBN 978-3883312200

19,90 Euro