Beijing Design Week 2016

Hipster in Hutong

‘You can find anything in China, you just have to find it first.’ So said Maurice Li, co-founder and grandly named ‘Principal of Brands’ at the new Chao boutique hotel in Beijing, as he conducted a guided tour of the premises, commenting on difficulties of sourcing Chinese suppliers and designers for all the hotel’s fixtures and fittings – from the bespoke furniture to signature soap for each and every room. These statements can be applied, without too much difficulty, to this year’s Beijing Design Week (BJDW) in multiple ways. As the pressure to position local lifestyle and consumer brands in the Chinese and the international markets is most certainly one of the main reasons why the city and therefore to all intents and purposes the Chinese government itself takes the stage as one of the main sponsors of this huge, massive, glittering Design Week and its multiple, in part highly commercial sales shows. The goa: to strengthen local products to such an extent that they can at long last seriously rival the foreign luxury brands which have to date fed the growing demand generated by a constantly expanding group of well-off Chinese consumers.

At the same time, Li’s comment also poignantly sums up the giddy surfeit of offerings on show at what is now the seventh Beijing design fest. Almost each of the countless event venues seems to have its identity graphics and its own thematic focal points, muddying any sense of a uniform BJDW concept. Presumably, you could have found anything and everything at this BJDW. But how to find it? And above all how to manage the sheer volume?

Everything is bigger in China

The BJDW is a web of activities and events, one which the two block-like un-indexed guide books, of 900 and 500 pages respectively, fail to clarify completely. It is divided into nine main parts, with over 550 separate activities such as conferences, lectures, workshops, exhibitions, pop-up shop displays, walks, and public performances. You would probably only have managed to cover this absolute glut of offerings if you had spent all-day everyday from Sept. 23 to Oct. 7 doing just that.

Even the logistics of getting to see a fraction of these activities and events was tricky – for the focus areas and design hubs are widely spaced across this enormous city. The only means of transport that enables you to get round Beijing above the ground quickly is a bicycle, a real health risk more due to the awful pollution levels than owing to the crawling cars that surround you. The therefore best option is probably to go underground via the city’s metro system, which since its vast extension for the 2008 Olympics covers much of the city – although this commonly necessitates a fair walk at either end. Smart City? The first proposal that comes to mind would be to set up a functioning bikcycle rental system at each metro station. Purportedly you can get anything in China!

On arrival at any one design district or hub, you then find out that most of the exhibitions are in themselves the size of small towns requiring a good few hours to visit and wander around if you want to inform yourself in greater depth rather than just snap a few digi-photos. This was true of the designers’ open studios, large commercial exhibitions in the vast former gas power station in the 751D Park Design District – which functions as something like the hub of the Design Week – or in the very, very many installations and performances that form the ‘Light Festival’ in and around the Taikoo Li Sanlitun shopping mall, itself a city district in its own right with 19 buildings, subdivided into two zones and developed according to a masterplan courtesy of Kengo Kuma.

Design City? Smart City? But how?

Given the challenges of getting between the various venues, it seemed decidedly appropriate that the focus of this year’s BJDW was above all on the city itself – with ‘Smart City, Design City’ as the main theme, aiming to ‘provide design solutions for …challenges in urban development’. This was a refreshingly grounded aim given so many design festivals still remain sequestered international showcases for beautiful pricey home interiors. Here was one that seemed intent on connecting up the design dots up from the object to the urban scale. And so on their in part arduous journeys between the shows, visitors had sufficient time to think about how to apply what they had just seen and heard to Beijing’s specific problems.

Incidentally, this focus on design as urban problem solver is one that has been steered since 2013 by the Creative Directorship of Beatrice Leanza at BJDW. Although her stepping aside from the role this year – and not being directly replaced – perhaps goes some way to explaining the loss of focus on the core themes formulated at this year’s edition.

Micro-modernization of historical districts of the city

This does not apply to the two large urban redesign projects in the downtown districts of Dashilar and Baitasi, which Leanza co-initiated and which formed a major focus of this Design Week. Today, both districts are defined above all by hutongs, those traditional residential streets and courtyards made up of a plethora of small segments, and which until only a few years ago tended to be demolished in favor of more modern, large residential properties, but are now heritage listed.

Some knotty and very Beijing-specific urban issues arise as regards infrastructure and revitalizing these districts. Indeed, these two hutongs seem at first sight after a modern planner’s heart, constituting inner-city, high-density yet low-rise residential neighborhoods that are pedestrian friendly – indeed almost free of cars due to the scale of the streets – and still with a strong community ethos from their long-term residents.

But now the hutongs are being preserved, the very problems that a few years ago their razing was meant to solve have come back into focus: extreme overcrowding – with seven families occupying courtyard houses designed for just one – and a lack of basic mains sewerage and sanitation, meaning residents have to use communal wash-houses and toilets connected to sewage tanks – as well as from a lack of public space beyond that of the narrow streets. In addition to these physical issues there are economic ones too, for though these are residential neighborhoods, many central Beijing hutongs were traditionally hubs of commerce and small scale industry too – and in the case of Dashilar, a center of the Chinese finance industry. With this commercial focus long since sidelined by the hutongs not being able to offer the scale required for today’s mainstream retail and business, the need is now there to find new economic and business models to sustain these areas.

The hipster trap

The reworking since 2011 of the Dashilar hutong, adjacent to Tiananmen Square, is one of the first attempts to physically and economically regenerate a hutong in Ginca. In what is described as ‘an organic revitalization process of micro-renewal’, architecture and design have been used to shape some spectacular pilot projects in old courtyard houses, while at the same time designers and architects (as well as other vocational groups designated ‘creative’) are themselves the target of these interventions. There is an explicit hope that creative companies will locate to these districts and that these will thus swiftly emerge as Beijing’s new design hotspots.

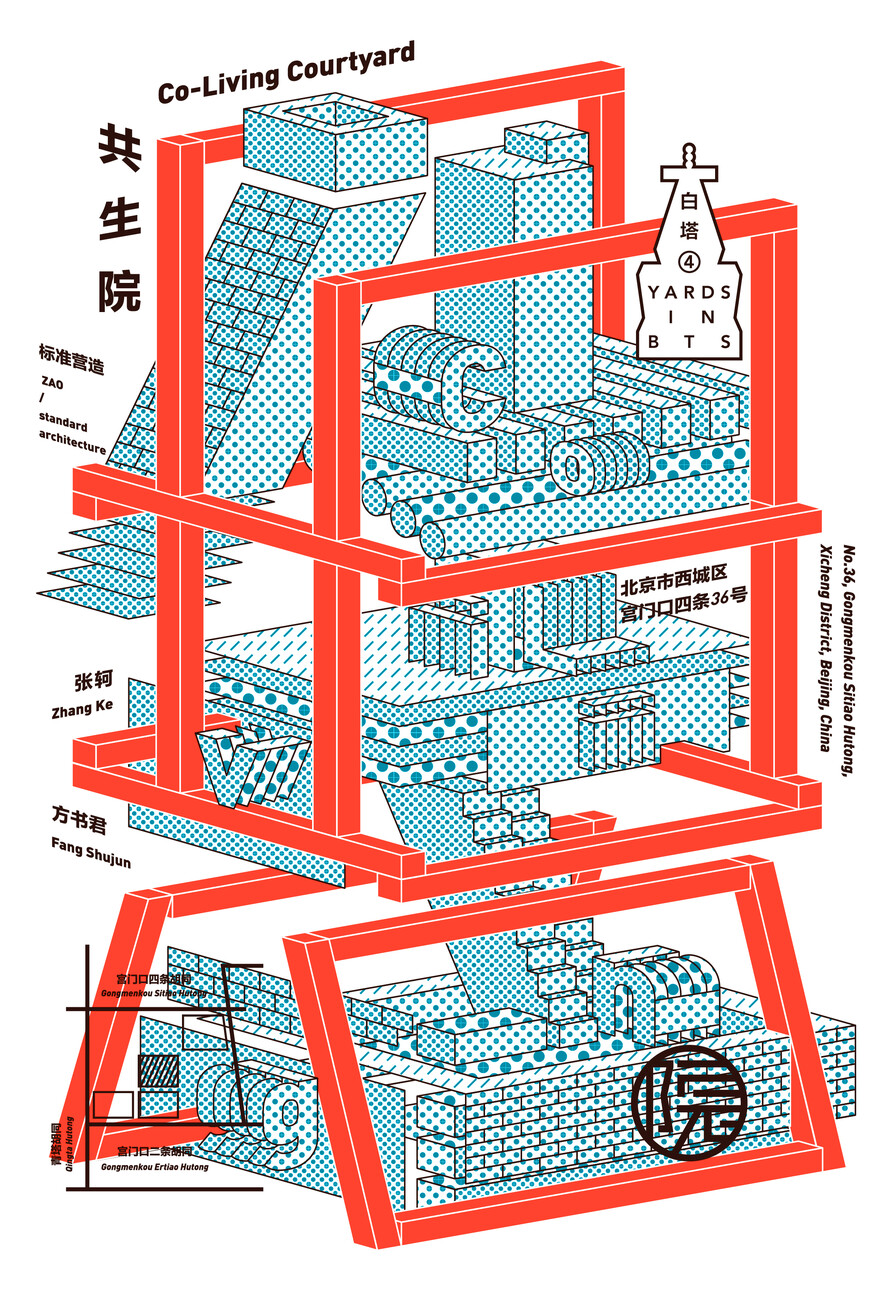

The logic does indeed work: The process has been widely publicized over the last couple of years in the architecture and design press, in particular the highly photogenic architectural insertions by Zhang Ke and his office ZAO/standardarchitecture. He proposes running a new structure through the traditional houses and courtyards, enabling new uages or skillfully supplementing the existing offerings. Not quite as photogenic, but more widely applicable is the system of insulated panels by People’s Architecture Office. The new structure eliminates some of the weaknesses of the historical builds without destroying them.

These reports have made Dashilar well known among creative urban hipsters. Streets like Yangmeizhu Xieje are now lined with countless smaller design, fashion and jewelry shops – as well as others like UN1INC., one of the best art book and art magazine stores in Beijing. Coffee shops and bars are starting to appear here and there. Indeed with many hutong architectural insertions just becoming the offices of the architects who designed them – as is the case with People’s Architecture Office – and with the UN1INC. feeling the need to host a dedicated Kinfolk magazine display and a Freitag concession out back, the question whether the area is really a test bed for new models of urban regeneration or just passes by the needs of the original residents and we are witnessing fast-forward gentrification by prosperous hipsters.

Learning from Dashilar

The project in Baitasi in contrast seems to have already learned from these problems in Dashilar. The ‘Baitasi Remade’ project, which launched this year, is what Beatrice Leanza now heads as Creative Director, so perhaps as a result it feels a bit more like a concentrated and more coherent Design Week. It has a uniform visual concept with a clear overall approach. This included a series of projects, pop-up shops and temporary installations together with more permanent hutong courtyard interventions by architects. In addition, a Global School, set up in the old market building, hosted exhibitions, education workshops, competitions, talks and discussions. The school is intended to become a fixture and permanently accompany the revitalization process. The intention to anchor a durable and refreshingly holistic design approach to urban renewal, aiming to ‘integrate communal engagement’ into the ‘architectural and infrastructural upgrading’, i.e., the hutong’s modernization, through dialogue.

The shape such an architecture can take can be seen already from the prototypes on three architectural interventions in adjacent plots: Two courtyard houses and an existing two-story structure have been transformed. ‘Courtyard Hybrid’ by Vector Architects is a timber and glazed structure sensitively inserted into the existing build destined to enable new usages in addition to residential purposes. The ‘Co-Living Courtyard’ by ZAO/standardarchitecture attempts the same, again mainly consisting of concrete but much more subtly than in the projects in Dashilar. Most striking are the series of extraordinarily expressive spatial interventions in the two-story building by Xu Tiantian of DnA. Here she has cut out and rounded off corners of both walls and floor slabs, enabling light to drop beautifully into its depth. While the ‘Co-Living Courtyard’ will be providing the project HQ space Baitasi Remade itself, these spaces as a whole offer a new facility that will become centers of communal activity for the hutong’s residents in time. As with the “Global School”, the focus of all the projects in Baitasi is on linking local needs with global knowledge, which is promising, at least in the announcements and principles.