On the Curiosity of Being in the World

David Kasparek: I truly find your recently published book interesting. Also because your work is complex and contains so many different layers: photos and texts, art, design, urbanism, and architecture. So my first question is: How do you define your work? Are you an artist, designer, essayist, teacher, architect?

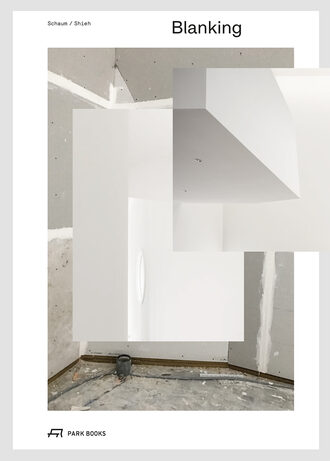

Troy Schaum: Well, I was always very interested in building; we were concerned with engaging in building scale questions. Especially when you are starting out, you do work at many different scales and contexts that include urban research, installations, and exhibitions. The book “Blanking” itself arose from a solo exhibition at the University of New Mexico in 2018, and like that exhibition it is an attempt to engage in self-reflexive building practice. In doing so, one of the things the book resists is the pressure we feel in the US context to reduce one’s work to a kind of singular brand or research focus, but instead it encompasses the entire complexity of designing buildings in the world. Our projects engage with many different realms simultaneously and we wanted to show that it can be a sometimes messy, sometimes provisional, sometimes ad-hoc way of operating.

Since you mentioned the US-American context of building and urbanism: Where do you see the differences between the American and the European context?

Troy Schaum: In the US context, the state is much less of an actor in shaping the built environment. We work in places from the US Northeast to Texas, and it steadily decreases the closer you move toward Texas. The idea of a purely public project, that is, state-sponsored, or of a state as the sole actor, essentially does not exist like it does in Oslo for example. Every project there is a public-private partnership, or private philanthropic actors are behind most of the “public” work we do. Indirectly, through many European colleagues, I know that the state is much more active there, particularly in Western Europe.

And do you see it as a problem or rather as an opportunity?

Troy Schaum: Not a problem, but it is an issue. It is a shortcoming of the system, on one hand. Is it a problem, in the sense of, can it not have good results? No. It takes a certain optimism to be an architect. Something architects must do is grapple with what the future could look like for us, with all the precariousness and opportunities that this entails. Therefore, I think there are many opportunities in the model in which I operate, particularly in the American West and in many places where I work. In many places where we work, like in parts of Detroit or Houston, if you have a good idea and imagine a future that is better than what we are currently experiencing, then people are willing to support it. No one will say: "We don't do it like that here in Houston," In my eyes, that is also why Frank Gehry came from Los Angeles in the time he did. Here, you have a situation where there are other opportunities for experimentation — different from the kind of experimentation you might see in Basel, New York, or parts of Europe.

The book was created together with Rosalyne Shieh, with whom you have collaborated since 2009. May I ask why you ended this collaboration?

Troy Schaum: Yes. Rosalyne is a professor at MIT in Cambridge and I am at Rice University in Houston, and after about 15 years together, a pandemic, life, families and the like, it just became difficult to maintain. It is mainly practical reasons. This book is distillation of what we have done together, and also an outlook on possible futures.

I would like to take one step back again. When did it become clear to you that you wanted to make what you are doing today your profession? And: is that the same question as when you decided to study architecture?

Troy Schaum: I guess I can tell the story in different ways (laughs). I decided to study architecture before I knew I wanted to make it my profession. When I was younger, before college, I liked theater, art, drawing, writing, and making things. I had a friend, and fellow high-school literary magazine editor, who went to university a few years before me. I visited him at college, while he was at an architecture school at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, VA. Wow! I mean, what the architecture school was like back then in the early 90s — that's really ... (hesitates). I have to elaborate a bit: There is this Apple commercial where they squeeze all the things we do creatively into the iPhone. School was the precursor to that state back then. We had darkrooms, printmaking, pottery, we could borrow cameras, we had a metal workshop. I thought: "Oh my God, you can go to college and do all that! That's an education!" And so I enrolled. I was primarily enticed by this creative environment and only afterwards was I captivated by the complexity of the architectural profession. When I finished my studies and started practicing, I understood that I seriously wanted to pursue it as a profession. I moved to San Francisco, right around the time the internet emerged. There was a lot of creativity in this field back then, and many wondered whether this virtual space that was emerging could be something entirely new. Architecture at that time felt very haptic, like learning how to make barrels or something. And with the emergence of the internet, the questions arose: "What, are you still doing that? Are you still working on real, material problems?" The future seemed to be an immaterial practice. But the more I got involved in the challenges and the kind of collaboration surrounding architecture, the more I realized what an amazing practice it is. I get bored without the kind of stimulus variety that architecture offers.

You studied at Princeton University and Virginia Tech, which you have already mentioned. Were there teachers there who were important to you, perhaps even formative?

Troy Schaum: That's a good question. Rosalyne and I met at Princeton. We were in the same studio there with Paul Lewis, who is a partner at LTL Architects. Stan Allen had just taken on the deanship and shaped a discourse that brought personalities like Sarah Whiting on board, who became my thesis advisor and later a kind of mentor as dean at Rice University.

And Virginia Tech?

Troy Schaum: Virginia Tech was a wild place when I was there. One teacher I could really highlight from there is Hunter Pittman. He was a very humble professor, who hired me for my first professional experience. He had a small office in his attic, and I made hand drawings, ink on Mylar drawings, for a couple of commercial buildings he was working on in the area that still exist today. I actually visited them three or four years ago for a talk, and I think they still hold up well. They are simple, commercial projects. But I learned how to think through details and how to understand the kind of limitations of a specific type of American building. He was a generous boss and mentor.

In Germany, there is the saying: A design can only ever be as good as its client. The site, the task, the chosen materials, and the resulting construction are also important for the design. Time also plays a role in finding form and space. Are there certain design strategies that are similar in your work anyway, certain steps in the process that are comparable regardless of the project?

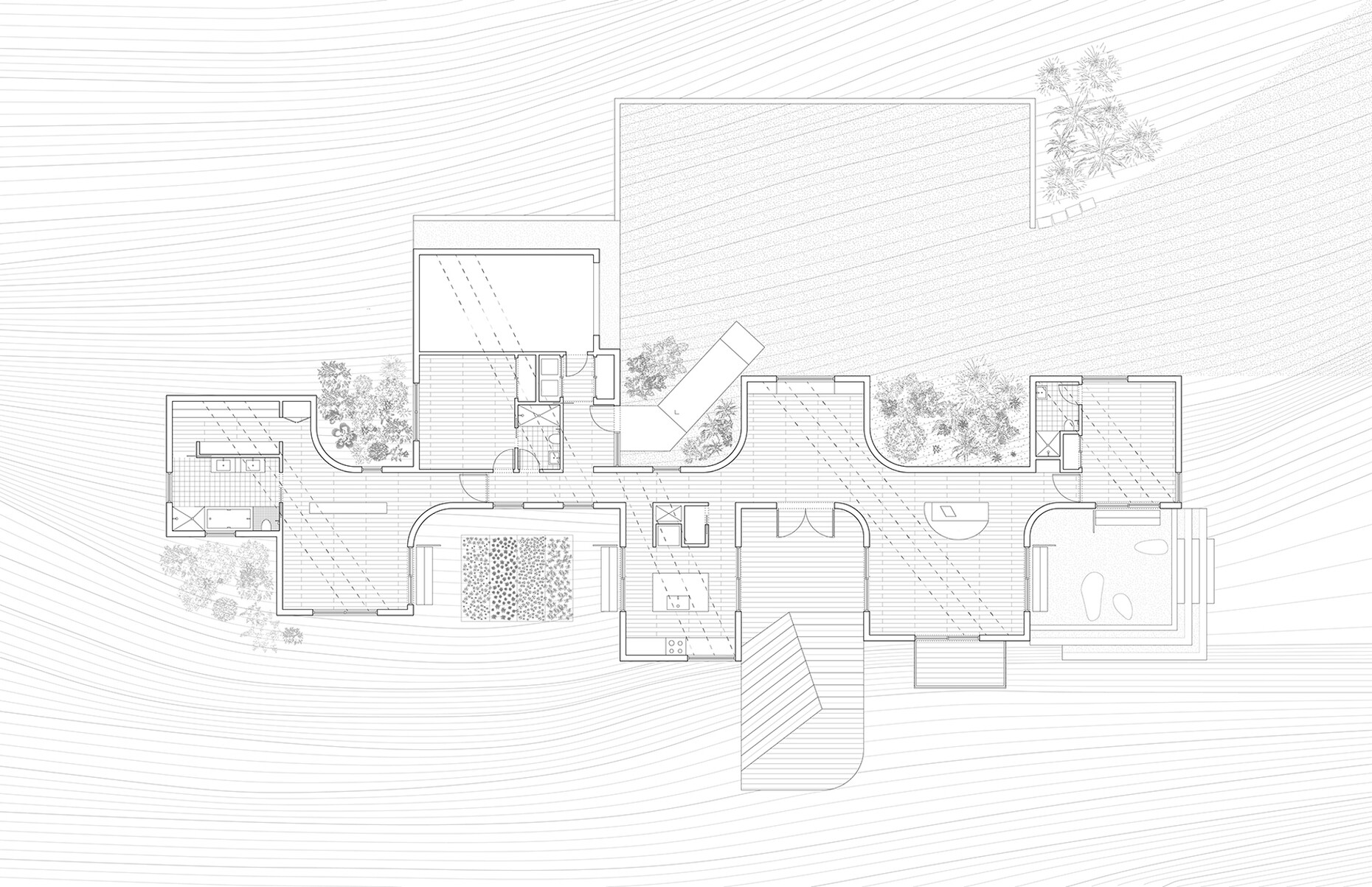

Troy Schaum: One of the things that has really preoccupied us — and this is related to the idea that a building practice is at the center of our work, even if we execute it in very different ways — is that there is a problem of form. You can partly see this as a lineage from people like Stan Allen and Sarah Whiting, who contributed to your book. At the center of our work is the question of how we can use form, not as an end in itself or a linguistic problem, but in a sophisticated way as a tool. As a tool to solve the representational problems of different levels: how do we draw the city, how do we think about the place, and which diagrams do we use? When you look at projects like the Shenandoah House, or the Transart Gallery, there are indications of how we use formal approaches, how we think about how objects are positioned relative to surfaces, and what kind of tension arises between the individual objects. We are also concerned with the way one thinks about a system of objects and how that relates to monumentality.

So, do you begin the design with form?

Troy Schaum: We don't want to start and end the project solely with form, but there is always a point where these techniques come into play. We want to see the place, we draw it, and try to understand it through diagrams. You see this in the Kaohsiung Pop Music Center design through the grid of circles. In trying to draw the place, we see it as through a lens that leads us into a kind of space of autonomy. We try to understand the space from the outside before we come back to it to build a new space with form.

How important is teaching at the Rice School for you personally and for the practical work in your architectural office?

Troy Schaum: I long viewed teaching as something that gave me some space to build a practice and granted me a bit of freedom and autonomy from the demands in my practice. It really forces me to step out of the daily business of my practice and reflect. I don't know what it's like where you studied, but we teach studio on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday afternoons. So even though it takes up a lot of time, it is also a space where you can step out of the everyday and reflect precisely on what you are doing and saying. Facing the students, you have to justify why you say this and do that. Especially with fundamental things. The special thing about the university is that the kind of interaction there forces us to think about what the problems will be in the future. We can initially address actual problems there as broad questions. How we deal with globalization, for example, with its potential but also with its small and large tyrannies? Alternately, material practice currently seems to me to be heavily charged with questions about embodied carbon in construction and handling materials, which we are looking at in my studio right now. Currently, our students deeply concerned with such material practices. That's why I think it is increasingly becoming a question of how we use tools of representation and communication to study issues like this across the entire industry. More and more it seems everyone, from the construction worker to the developer, is on the same platforms, and how we shape the city in these spaces, with information, with representational tools, are becoming more instrumental in studying these problems.

In Germany, there is quite a big debate about banning construction, in practice and at the universities. The problems that construction causes are obvious: carbon dioxide emissions, resource scarcity, huge amounts of waste generated during construction and demolition ...

Troy Schaum: Many people here in the US also ask whether we should build on undeveloped plots at all. Can we only build adaptive reuse, or only on already developed areas? In some regions, like Houston, it is a difficult question to answer because of population growth and migration pressures we see. And so you are really trapped: Can one really set a kind of absolute limit and still satisfy basic human needs, like affordable housing, given the scale of that population growth. That is certainly different in different places, but they are the questions we should be asking ourselves, absolutely.

Finally, back to your book "Blanking." You wrote a beautiful text in it about wonder. Can you briefly explain to our readers why wonder is so important to you and your work?

Troy Schaum: That has something to do with the question of when I decided to become an architect, or what architecture is to me and to us. Ultimately, the entire book is about a concept of our practice as an action between teaching, academic research, and building practice. It is about a kind of curiosity about how one lives a life and how one is in the world. Architecture is a vehicle for grappling with this and for learning from people and material objects. And so, on the one hand, the book tries to provide a justification — if architecture even needs a justification — for what drives us, outside of utility-oriented conventions. "Blanking" tries to explore, with a series of incomplete themes, what drives us. The collaboration between Rosalyne and me was always a collaboration of two individuals who had some shared agendas and some differing agendas. And we learned from each other and about their own curiosity in this way. And that is what my text "Wonder" tries to demonstrate: to clarify a motivation behind such a practice Wonder also tries to provide an argument for our academic work. In universities, there is great pressure to define one's singular research, one's production, like a scientist, in a very, very narrow category, which design practice cannot deliver. Building practices lean too hard on this often appear either naive or overly derivative. With the text I am trying to provide an argument — and we are trying to do it with the book — that it is okay to be somewhat broader and somewhat more versatile as a design practice. Because that is what we do. We synthesize, we summarize, we try to react in a much wider range than many of our colleagues, next to whom we are placed, do, for example, in natural science disciplines.

Blanking

An Annotated Archive of Projects and Thoughts on Architecture

The work and vision of Houston-based architecture firm Schaum/Shieh

By Troy Schaum, Rosalyne Shieh

Park Books, 2025

Language: English

Paperback

336 pages, 198 color and 89 b/w illustrations17 x 24 cm

ISBN 978-3-03860-400-6

45 USD