Spotlight on Women Architects – Marie-José Van Hee

Although she's been working as an architect for 50 years now, and has had over 250 of her 400 projects built, including some outstanding residential buildings, architect Marie-José Van Hee is hardly a household name, even in her own country Belgium. One reason for this is surely the small scale on which she's mainly worked; the vast majority of her projects are single-family homes, as well as a few smaller housing developments, and it's only been in the last few years that public buildings, squares and a bridge been added to her portfolio. A second reason for Van Hee's obscurity is probably her consistent refusal to be pigeonholed into one style. Her houses are not radically modern concrete structures like those of her countryman Juliaan Lampens. They are no more along the lines of postmodernism than they are of deconstructivism or the current focus of sustainability. Nor do her homes provide spectacular photos that could be disseminated throughout the internet or in the glossy anthologies of the 50 Best Homes in order to promote sales. Instead, from the very beginning, Van Hee focused on a well-crafted, intricately thought-out architecture of reduction and concentration, and on open spaces with as many pathways and uses as possible. Hers is an architecture oriented to light and the changing seasons, with a precise use of materials. It is an extraordinarily composed and appealing art of building – and this is exactly why it's important, in today's turbulent times, to take a closer look at her thoughtful, multifaceted work.

“I had to fight for everything”

Born in 1950 in Bachte-Maria-Leerne, between Deinze and Ghent, her parents sent her to boarding school when she was ten. It was her art teacher, a nun, who recognised Van Hee's talent and encouraged her to study architecture – against the wishes of her parents and the headmistress, who said architecture was only for men. But Van Hee was accepted at the famous Sint-Lucas School of Architecture in nearby Ghent, where women had just been admitted to study architecture. In her year, Van Hee recalls, there were just four female students out of 80. “I guess I really am a product of the 1968 movement,” she says, “I like freedom. And I don't like strict rules”.

She finished her studies in 1975, when she was 25. There was an economic crisis in Flanders, the construction industry was idle and it was therefore doubly difficult for women to work as architects. “I had to fight for everything”, she says. Van Hee, whose thesis was on the gardens of the French king Louis XIV, began her professional life working with landscape architect Paul Deroose, but moonlighted as well, and began to increase the number of her own commissions. In 1986, together with Johan Van Dessel, she founded the office VDVH Associés in Brussels, and in 1990 finally officially established her own office – although she had already been designing and building residential buildings for 25 years by then.

Poetry in dialogue

Her architecture is often described as “spatial poetry”. She herself says that she always starts by planting a tree – she still feels very much like a landscape architect. Also, many of her designs have a courtyard as the building's interior landscape space. Where there is no such courtyard, the connection between inside and outside is immensely important to her. Apart from that, she cultivates a serious, almost ascetic architectural style that takes the spatial structure and its proportions seriously – creating freedom for the users and residents precisely because of this. Her design is somewhat reminiscent of Japanese rooms, except that Van Hee's buildings, despite their austerity, rarely seem too cool or forbidding, and on the contrary are cosy and comfortable. They invite you to use them and embellish them as you wish. “Architecture is not art”, says Van Hee. “Art has the freedom to be useless. Architecture isn't allowed to do that.”

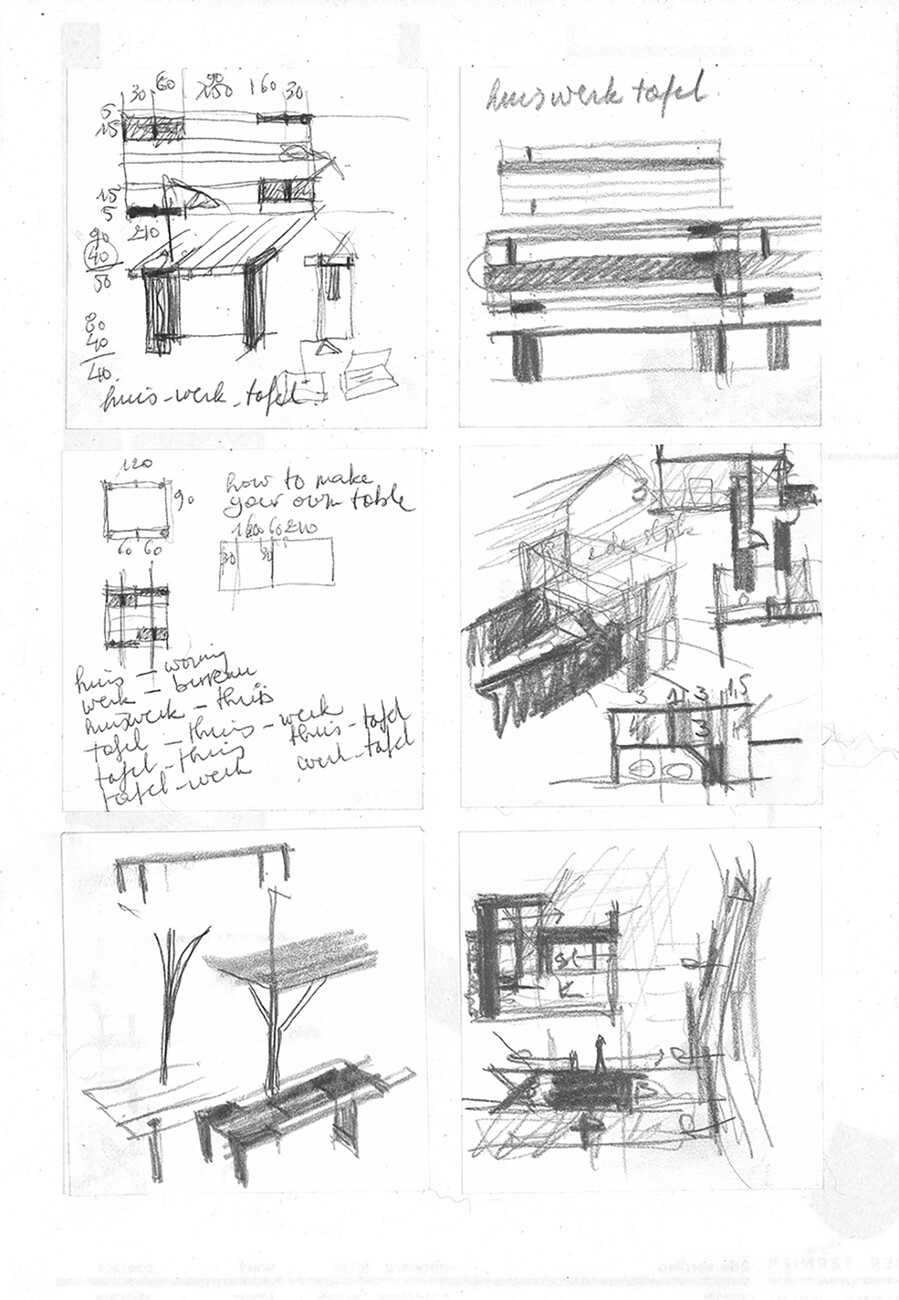

It's thus fitting that Van Hee is not an aloof artist, but instead seeks dialogue regarding her architecture. Every project begins with a conversation, she says, because everyone comes with their own individual ideas. “I always start with a sketch to see if we can find each other.” The biggest challenge in recent years, she says, is younger clients showing their mood boards on Pinterest and saying they want a house like that. “I tell them that I'm probably not the right architect for them then, because they obviously want something else.” Sketches play a central role in Van Hee's way of working. They are her design tool. Moreover, her architecture is slow: She takes time to talk and she takes time to get to know the building sites and their surroundings. From this she derives moods, which she transfers into sketches that become more precise step by step, slowly becoming spaces and finally houses. “My architecture is not meant to determine how people have to live, but to create possibilities.” Again, it's about freedom – not only for her, but also for those who live in her buildings. She works slowly, and she's aware of that. But her patient cautiousness carries over to the houses she designs: “Most of my clients say that the houses feel like holiday homes. They find peace there. They find a sort of deceleration in my houses. This means a great deal to me.

Market hall of possibilities

And thus designing residential buildings was partly Van Hee's decision, but to a greater extent it was simply what was possible for her as an architect. From 1990 onwards, she began an increasingly close collaboration with two of her former classmates: Paul Robbrecht and Hilde Daem. Immediately after graduating, these two had opened their own office, Robbrecht en Daem Architecten, which is now one of the best-known Belgian offices. Together with them, Van Hee began to work on commissions that extended beyond private residences – an art gallery in Elsene (1990-1992), the complete redesign of Leopold De Wael Square in Antwerp (1997-1999) and, probably their best-known project, the redesign of Emile Braun Square in the centre of Ghent (1996-2012). In the centre of this square, Robbrecht, Daem and Van Hee placed a large wooden roof, open on all sides, on four concrete plinths. With the strangely familiar silhouette of a double-gabled roof, the architects created a new centre of gravity for the completely asymmetrical square, which until then had been used mainly as a car park. The result was a new centre that can be used for a variety of activities. One of the concrete plinths even has a fireplace set into it. “We had the idea that the centre of the city is a kind of home”, says Van Hee. And this idea is now being actively embraced: festivals, concerts and weddings all take place under the roof, and some people even set up tables and eat there. It's a completely new typology: the market hall of possibilities. The project has been published worldwide and has won many awards, including being shortlisted for both the European Mies van der Rohe Award in 2013 and the European Prize for Public Urban Space in 2014.

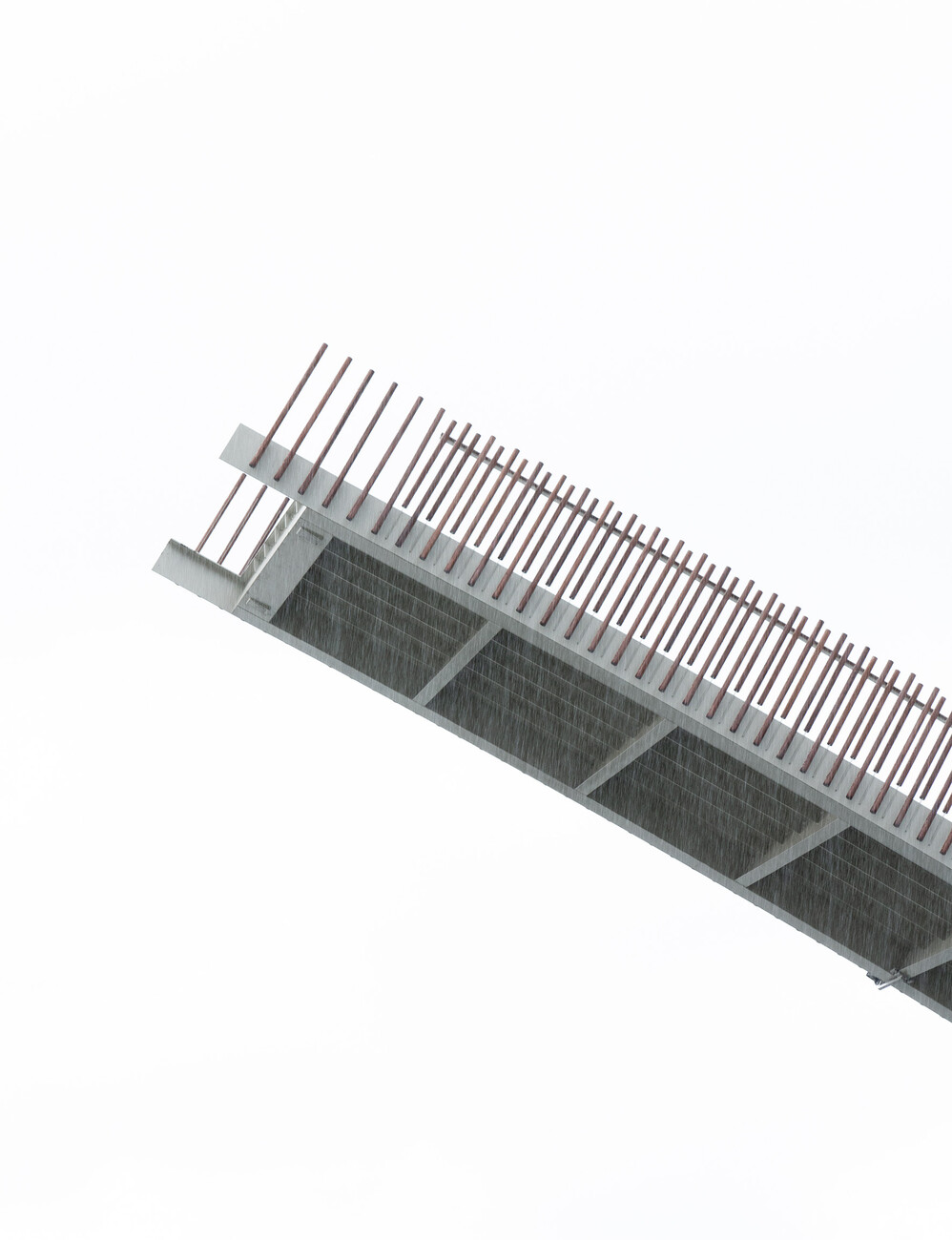

Since then, Van Hee has also received major public commissions of her own: the conversion of an old industrial building into a fashion museum in Antwerp (1999-2003), the transformation of a warehouse in Ghent into a performing arts centre (2004) and the ongoing, large-scale redesign of the city's riverbanks in Deinze (since 2009). One of Van Hee's dreams has also come true, i.e. the commission for the Brielpoort Bridge near Deinze (2018-2021) – as a structure that creates an immediate, visible connection, it is perfect for her portfolio, which seeks connections everywhere. The 73-year-old currently has seven to eight permanent employees working in her office. Among them are always women who, as Van Hee notes, subsequently open their own offices as a matter of course. “And whenever I think out loud about closing my office, they say, 'No, no, don't stop. You're a role model for us.' It seems I wasn't just fighting for myself, I was fighting for them.” Van Hee is happy about this situation, of course, and she's still not thinking about retiring. She probably wouldn't even know how to stop working.

The bulk of her work, however, still consists of small, private residential buildings that to this day have been built almost exclusively in Flanders. This architecture, however, has by now acquired such a certainty and maturity that it is also attracting international attention. For instance, the house with a doctor's surgery in Opwijk (2005), the HdF house in Zuidzande (2007) and the V-D house in Ghent (2007), all of which have been reviewed in international publications. The renowned Japanese magazine A+U dedicated an entire issue to her in 2021, in which – of course – her residential buildings are prominently shown in all their wonderful silence. In 2019, Slow Publishing published a first, comprehensive monograph, appropriately titled More Home, More Garden. And the Flanders Architecture Institute (VAi) in Antwerp has invited her to put on a solo exhibition for the second time in almost 30 years. In this exhibition called Een Wandeling. A Walk, Van Hee doesn't highlight her own projects as much as she demonstrates the basic features of her architecture in a casual, matter-of-fact way. For example, she has had the exhibition rooms in the intricate VAi, which has been rebuilt several times, opened up to a large extent so that visitors can take a long walk – similar to the way she almost always creates several routes through the residential buildings she designs. She has also had the asphalt forecourt opened up in one area so that a tree could be planted there, in keeping with most of her projects. In this exhibition, Van Hee's own projects are simply laid out as voluminous books that can be carefully studied on specially designed lecterns – with the same great calm and concentration that are the essence of her magnificent architecture.

Marie-José Van Hee architecten. A Walk

Until 21 May 2023

Flanders Architecture Institute at DE SINGEL

Desguinlei 25, 2018 Antwerp

Opening hours:

Wednesday to Sunday, 2pm to 7pm

during evening events until 10 pm