Every age has its own style preferences. The 1950s wanted to condemn the Wilhelminian style architecture, the 1980s sneered at post-War modernism, and the present has/does not yet have any tolerance for the architectural testimony of the 1960s and 1970s. Architecture is based on cycles of appreciation noticeably different from those of fashion and design, the latter finding it easier to don a retro-look - and shed it again a short time later: The generation of children reacts fiercely to what the fathers achieved, in a manner almost reminiscent of patricide, while the grandchildren at times react with respect or even admiration. As regular as this change in perception may be, when it comes to assessing buildings and the decisions they spawn, it is not considered seriously enough: Seldom do architects take into account that the next generation is almost bound, in fact, predictably, will reach a different conclusion and this is not even used as an argument that judgment should be suspended until the younger generation appears on the scene.

This is currently a massive problem for the architecture of the 1960s and one which is becoming all the more pressing as the buildings have often fallen into neglect, are full of asbestos, face the need to accommodate new uses and meet energy standards. Should we tear down the 1960s to welcome the 2010s? And, even if prejudice tends to ignore it, there is the question of aesthetics, undermined: Concrete, densification and size, prefabricated (West) and precast (East), brutalism and rationalization, a belief in progress and technical euphoria, these are all considered the insignia of the 1960, a decade that brought forth criticism in the form of such catchphrases such as "inhospitality" (Alexander Mitscherlich), "the murdered city" (Wolf Jobst Siedler), "functionalism in building" (Heinrich Klotz) and "profitopolis" (Josef Lehmbrock).

But the 1960s are not just the age of shopping malls, administration centers, or for that matter, youth, community, cultural, recreational or the myriad of other centers, satellite towns, polygonal open-plan offices, endless grid facades and overly long building blocks. They are also characterized by experiments with materials and form, open structures and participation as well as avant-garde churches to compensate for the monotony of new residential areas. Gottfried Böhm's crystalline structures, Frei Otto's suspended roof landscapes, Hardt-Walther Hähmer's organically shaped theater in Ingolstadt, and Bernhard Pfau's large-scale theater sculpture in Dusseldorf are just as characteristic of the decade as is Sep Ruf's chancellor bungalow or Egon Eiermann's "Lange Eugen" in Bonn. Albeit labeled as lacking place and history, buildings in this decade did not mark a radical change but were determined by continuity. The general suspicion that the epoch was aesthetically bad forgets its actually amazing diversity.

The discourse on 1960s architecture is expanding and becoming more differentiated - as is becoming evident in North-Rhine Westphalia in an exemplary way, a state which has portrayed the visions of the decade from the district of Baumheide in Bielefeld and the Ruhr University of Bochum through to Cologne's Chorweiler suburb and Aachen University Teaching Hospital. The Museum für Architektur und Ingenieurkunst (M:AI), a mobile task force without a home base that selects locations for its exhibitions, conceived the exhibition "Architektur im Aufbruch" ("Architecture in Upheaval"), which makes a case for paying more precise attention through critical debate. The exhibition demonstrates how the scientification of architecture has dominated the art of building and paved the way for banal functionalism, citing exceptional examples of social intermixing and discussing the opposition of structure and sculpture, steel construction and in situ concrete, wall and scaffolding - all against the backdrop of Germany's strong focus Westwards, and this included its architecture. After its first stop at the Liebfrauenkirche in Duisburg (designed by Klever architect Toni Hermann), a sculpturally designed two-story building with a slightly sloping ceiling which was consecrated in 1960 and desecrated in 2007, the exhibition traveled to the Audimax at the Ruhr University in Bochum whose jagged concrete canopy is reminiscent of the "International style" of former Soviet Republic capitals. At both venues, the location was the first exhibit in a show which presented its models and plans on tables designed by Egon Eiermann.

Exploiting a ‘home' advantage, a symposium was held whereby the Cologne House of Architecture was moved into the Japanese Cultural institute, a building designed by Yoshimi Ohashi in 1969. Expanded to include "Buildings and complexes of the 1960s and ‘70s" and thus the decade which heralded the transition to post-modernism, the title already addressed a sore point - "An Unpopular Heritage?" it asked. It was by no means a rhetorical question given the many acute cases of threatened monuments, among them the Beethoven Hall in Bonn created by Siegfried Wolske, Wilhelm Riphahn's Cologne Theater, Gerhard Graubner's Wuppertal Theater and the "Tausendfüssler" (centipede) by Friedrich Tamms in Düsseldorf. Already numerous buildings have sadly been lost to demolition, among them, awfully, the House of Study in Düsseldorf by Bernhard Pfau, the Mercator Hall in Duisburg by Stumpf and Voigtländer, and the Cooling Tower in Hamm by Jörg Schlaich. Or is it perhaps that the increasing distance has already caused us to rethink? Vox populi, which was already raised in Cologne, complained, without neglecting to give examples, that "the majority of these buildings are felt to be ugly" as "concrete does not age gracefully".

It seemed as if the Rhineland monument protection representative, Udo Mainzer, had literally been waiting for this "correct and important" objection. He countered it by pointing out that earlier epochs also had to live with such deriding comments and thus called for equality in the face of the law: "We do not differentiate between the Renaissance and the 1950s, because, after all, building monuments make a statement about the people." Mainzer did not tire of emphasizing that monument protection makes decisions not on the basis of the aesthetics but on their value as testimonies. "What makes a monument is a technical issue, what becomes of it is a social issue."

The symposium concluded that more time should be taken for the buildings and this should be done, according to Cologne architect Walther von Lom, in order "to understand what was intended", thereby preventing defacements such as he has been forced to accept in his buildings. A member of the audience made an original suggestion in this regard, namely, that the onus of proof should be inverted, and every architect required to explain that a new edifice is better than the old building it is supposed to replace. As unrealistic as this may now seem, not least because of existing tax regulations, the impact this would have is certainly worthy of consideration and would be far-reaching. Monument conservators would become demolition experts.

Andreas Rossmann is the cultural correspondent for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung in North-Rhine Westphalia.

Church of the Bonhoeffer community in Bremen by Frei Otto; photo: Roland Kutzki

Church of the Bonhoeffer community in Bremen by Frei Otto; photo: Roland Kutzki

Audimax of Ruhr-Universität Bochum; © Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Pressestelle

Audimax of Ruhr-Universität Bochum; © Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Pressestelle

pilgrimage cathedral by Gottfried Böhm in Neviges

pilgrimage cathedral by Gottfried Böhm in Neviges

Theater Wuppertal by Gerhard Graubner; Foto: pillboxs

Theater Wuppertal by Gerhard Graubner; Foto: pillboxs

Elevated road "Tausendfüßler" in Düsseldorf; photo: Johann H. Addicks

Elevated road "Tausendfüßler" in Düsseldorf; photo: Johann H. Addicks

Theater in Düsseldorf by Bernhard Pfau

Theater in Düsseldorf by Bernhard Pfau

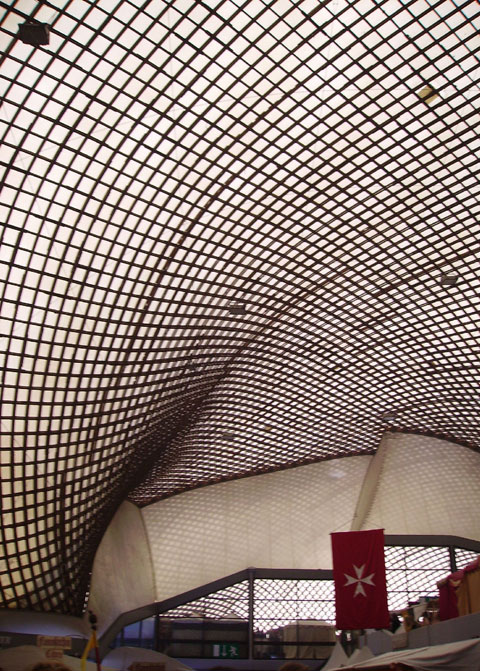

Hall in Herzogenriedpark Mannheim/Germany, roof construction by Frei Otto

Hall in Herzogenriedpark Mannheim/Germany, roof construction by Frei Otto

Skyscraper "Langer Eugen" by Egon Eiermann in Bonn; photo: Sir James

Skyscraper "Langer Eugen" by Egon Eiermann in Bonn; photo: Sir James

Elevated road "Tausendfüßler" in Düsseldorf; photo: Johann H. Addicks

Elevated road "Tausendfüßler" in Düsseldorf; photo: Johann H. Addicks

Theater Cologne by Wilhelm Riphahn

Theater Cologne by Wilhelm Riphahn

Chruch in Duisburg by Toni Hermanns; Foto: © Raimond Spekking / Wikimedia Commons

Chruch in Duisburg by Toni Hermanns; Foto: © Raimond Spekking / Wikimedia Commons

Theater in Düsseldorf by Bernhard Pfau, foyer

Theater in Düsseldorf by Bernhard Pfau, foyer