Arouse curiosity

Anna Moldenhauer: You studied interior design, worked as an art director for well-known advertising agencies and run a graphic design studio with your wife Natalie Opatz. Why did you start the architecture guide series?

Wilhelm Opatz: Inspiration? (laughs). In the summer of 2009, I read in the newspaper that the Church of the Resurrection in Aschaffenburg, a jewel from the 1970s, was about to be demolished. I travelled there and witnessed the heated discussions between supporters and opponents. On the way home, I wondered which architectural treasures will soon disappear in Frankfurt. I couldn't find any records, so I started researching them myself. The result was the book ‘Moderne Kirchen in Frankfurt a.M., 1948-1973’, which was published three years later by the Swiss publishing house Niggli Verlag. This was the impetus to also make the secular buildings hidden in the city visible. So basically a mixture of chance, interest and curiosity.

The architectural guides start with the year 1950, why not earlier?

Wilhelm Opatz: The architecture of the years before is also exciting, but it was so well-executed that it didn't appeal to me.

For each book, you make a selection of which buildings are to be presented. What criteria do you use to select them?

Wilhelm Opatz: I cycle a lot, which means you notice a lot and are able to stop, look over the fence and ring people's doorbells, which I do a lot. You only find out the stories behind the walls by talking to people. I also get advice from architect friends and can request information from the building inspectorate, among others. That helps me a lot with my research. When selecting ten buildings per book, you naturally have to include a few highlights, such as the Kleinmarkthalle in the 1950s edition. Then there are discoveries, special buildings that have hardly been recognised so far.

A huge amount of research is required for each book in the series, not only digitally, but also in the archives of the building inspectorate and in cooperation with the heritage office. How do you go about it?

Wilhelm Opatz: Beforehand, I draw up a list of up to 50 buildings of all kinds from the respective period, by both famous and less well-known architects. I submit these to the building inspectorate and thus obtain information on the years of construction and, in some cases, which people were involved in the building. Then I make a very subjective selection. The result is a cross-section of the building's history for each decade. I also aim to entertain, amaze and perhaps occasionally annoy with buildings that don't fit the cliché.

What was the last thing that annoyed you?

Wilhelm Opatz: When I can't gain access to buildings, like Commerzbank - but that was during the pandemic. I tried so many places, but the door remained closed. That was a shame.

What skills of persuasion were needed to look behind the doors of private homes for the architectural research?

Wilhelm Opatz: If the client likes my racing bike, then of course I'll get into the house (laughs). It's often little things, the mood of the day, my curiosity about the architecture, perhaps also my persistence. For one building, I spent over a year asking to be let in. With success: the building is included in the 2000 book, without a street name.

Many exciting buildings in Frankfurt am Main are very hidden. To find them, you spend a few hours on digital city maps, don't you?

Wilhelm Opatz: Just showing the well-known buildings would be too thin. The books should also be convincing beyond the region. For example, a pentagonal house in the Sachsenhausen district once aroused my curiosity, as I had read a short paragraph about it in an archive newspaper. So I searched the district on Google Maps, from top to bottom. I found what I was looking for, went there and asked nicely if I could have a look at the architecture.

Is there a building that you didn't know about beforehand and that made a lasting impression on you?

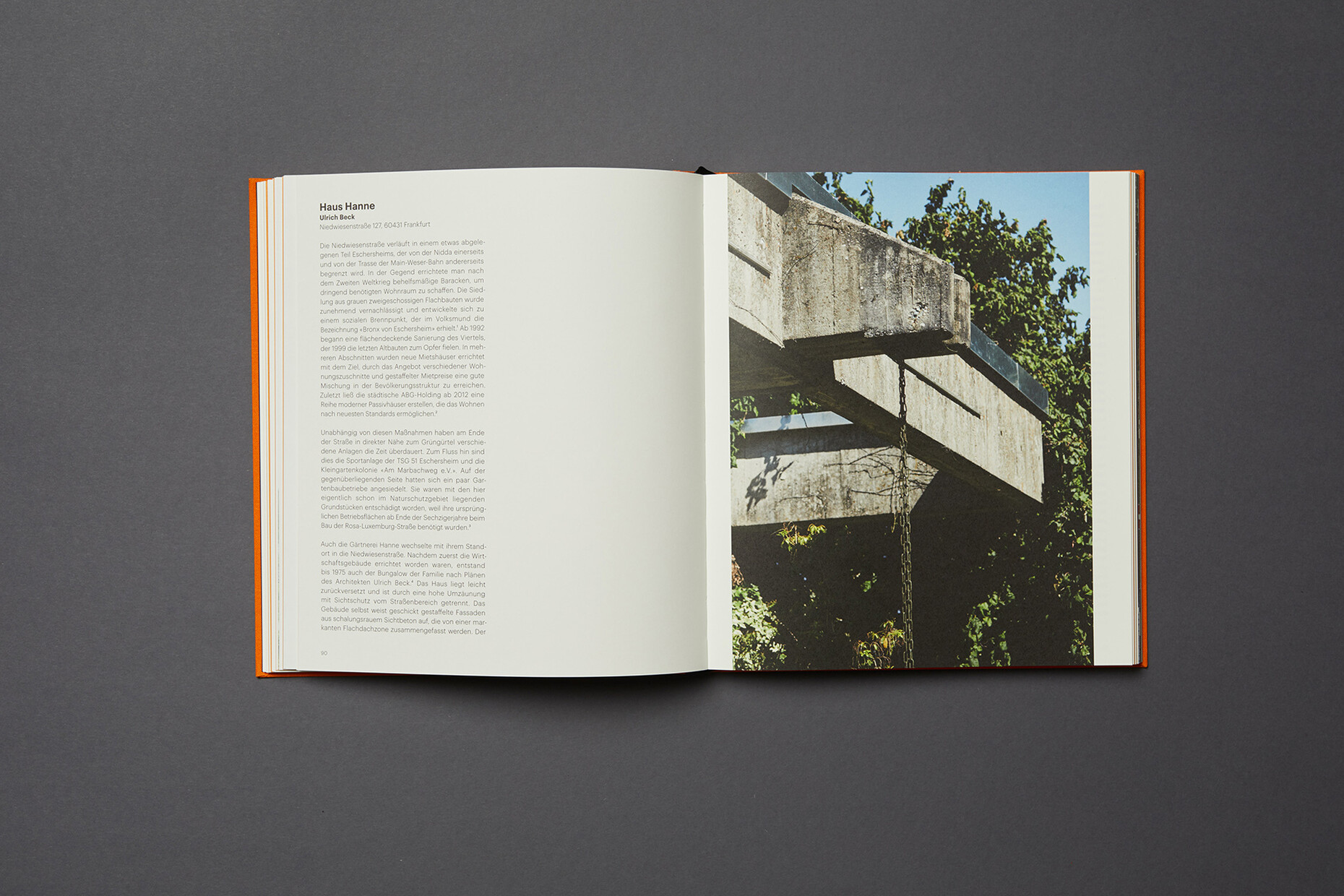

Wilhelm Opatz: There are buildings by unknown architects that don't appear anywhere, like Haus Hanne on the Nidda. I drove past it by chance and only saw a concrete spire hidden behind a large fence. There was a container next to it, so I climbed up to see more. Architecture in the style of Günter Bock, designed by an epigone from the provinces. When you enter, you feel like you've been transported back to the seventies; it was completed in 1975. These discoveries are coincidences. And sometimes the memory helps, like the beautiful bungalow in Praunheim by my former professor at the university, Till Behrens.

Was there an encounter during your research that particularly impressed you?

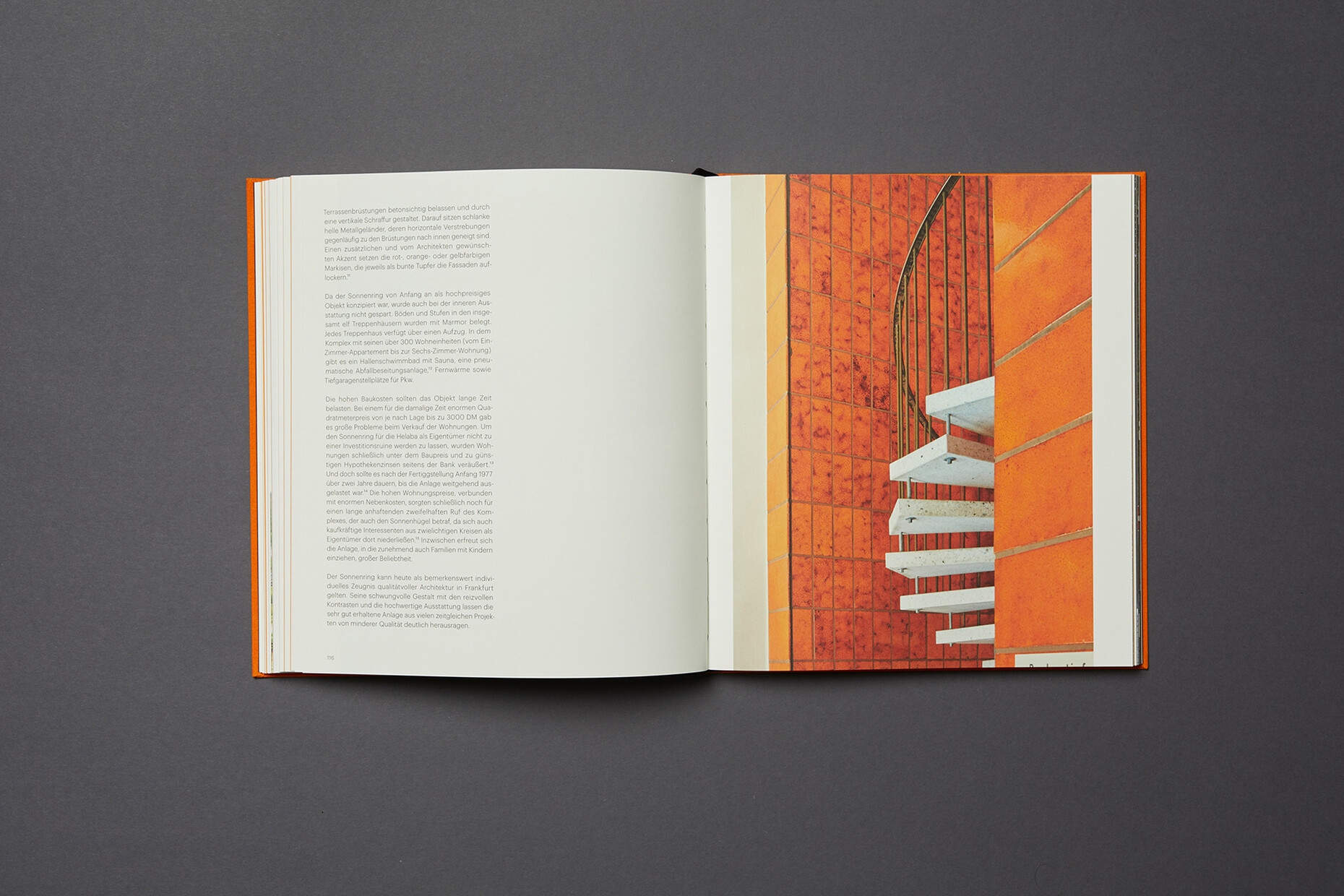

Wilhelm Opatz: The Sonnenring in Sachsenhausen by Günther Balser, for example. From the outside, the famous building looks unapproachable. Inside, there is a swimming pool that was completely designed in orange. The atmosphere there with the bathers was so cheerful and carefree, you wouldn't expect that. And, of course, many conversations with architects, which were very special. Like with Johannes Peter Hölzinger.

How has your view of architecture changed as a result of the series?

Wilhelm Opatz: I no longer judge the building on the basis of what you see from the outside. The discrepancy between the outside and the inside is unexpectedly stark. In the next volume, I show ‘House L’, a rather shabby barrack from the outside. Inside, the architecture is surprisingly different: immaculately white, with fine steel supports.

How do you choose the authors who write the texts for the buildings?

Wilhelm Opatz: The final decision is usually made by chance and three corners, like the contact with Kasper König back then. Then I research names in archive publications, such as the cultural historian and publicist Hermann Glaser. And then someone from Frankfurt comes and asks. These gentlemen are usually pleased that they can publish their knowledge again. The encounters are often unique. Like my meeting with the ceramic artist, former HfG professor and design historian Lore Kramer, who has an incredibly good memory. The lady sat candlelit on the sofa and talked about these turbulent times, about the philosophers Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer. That was an experience.

Did you remember a certain sentence from the conversation with Lore Kramer?

Wilhelm Opatz: ‘You'll be back soon’.

So, will you visit her again?

Wilhelm Opatz: Yes, I always come round for tea with the next architecture guide with me. Saying this sentence at an advanced age is something beautiful, something special. It's life-affirming. The enthusiasm for architecture, the interaction and the imagination of architects and clients is often a starting point for great conversations.

Georg Dörr photographs the buildings alongside Wolfgang Stahr. How did you find each other for the project?

Wilhelm Opatz: After the publication on churches, I realised that I needed a local photographer due to the flexibility required for the architectural guides. I knew Georg Dörr's way of working from my time in advertising agencies. I went through all the buildings in theory with him and the art historian Adrian Seib. I then visited the buildings with the clients and shortly afterwards with the photographer. There's an enormous amount of work involved. It wouldn't work any other way. From time to time there are guest photographers, like Peter Loewy, who told me many years ago that he wanted to photograph a particular building for me. Super guy. Or Moritz Bernoulli, a Frankfurt architect who lived in Mexico and the Netherlands for a long time. When he came back to Frankfurt, I asked him. I very rarely use archive photos, to be precise only in one case: the current architectural guide includes a house that was recently remodelled, the original state is no longer there. That's where I got involved. Otherwise, I only use current photos.

How do you choose the motifs?

Wilhelm Opatz: The photographers have a very trained eye, which is not mine. Georg Dörr and I have been a well-rehearsed team for over ten years, so I can trust him and let him get on with it. Each book has a dramaturgy, between three and six photographs are shown per building. It's important that everything fits together and creates a surprise. It's a kind of mix of the motifs that I see and that the photographer sees, because everyone has their own view. A common thread is perhaps the details that stand out in a house and that you then look for in every other building, such as banisters, door handles or special lights. It's not forced, it just happens.

Is your view of architecture characterised by your graphic design education?

Wilhelm Opatz: Sure. I come from the advertising industry, and it's fast-moving. Advertising makes a point so that it works. And so, in my opinion, there's no point in just showing the architecture as a panoramic shot, because that's not the point. It's about the moment, about what was previously unseen. I try to show details that you want to feel. You don't see them if the building is only shown in its full splendour. I'm interested in the corners where you can feel the concrete, the surfaces, the feel. I try to show that too.

Can you give an example?

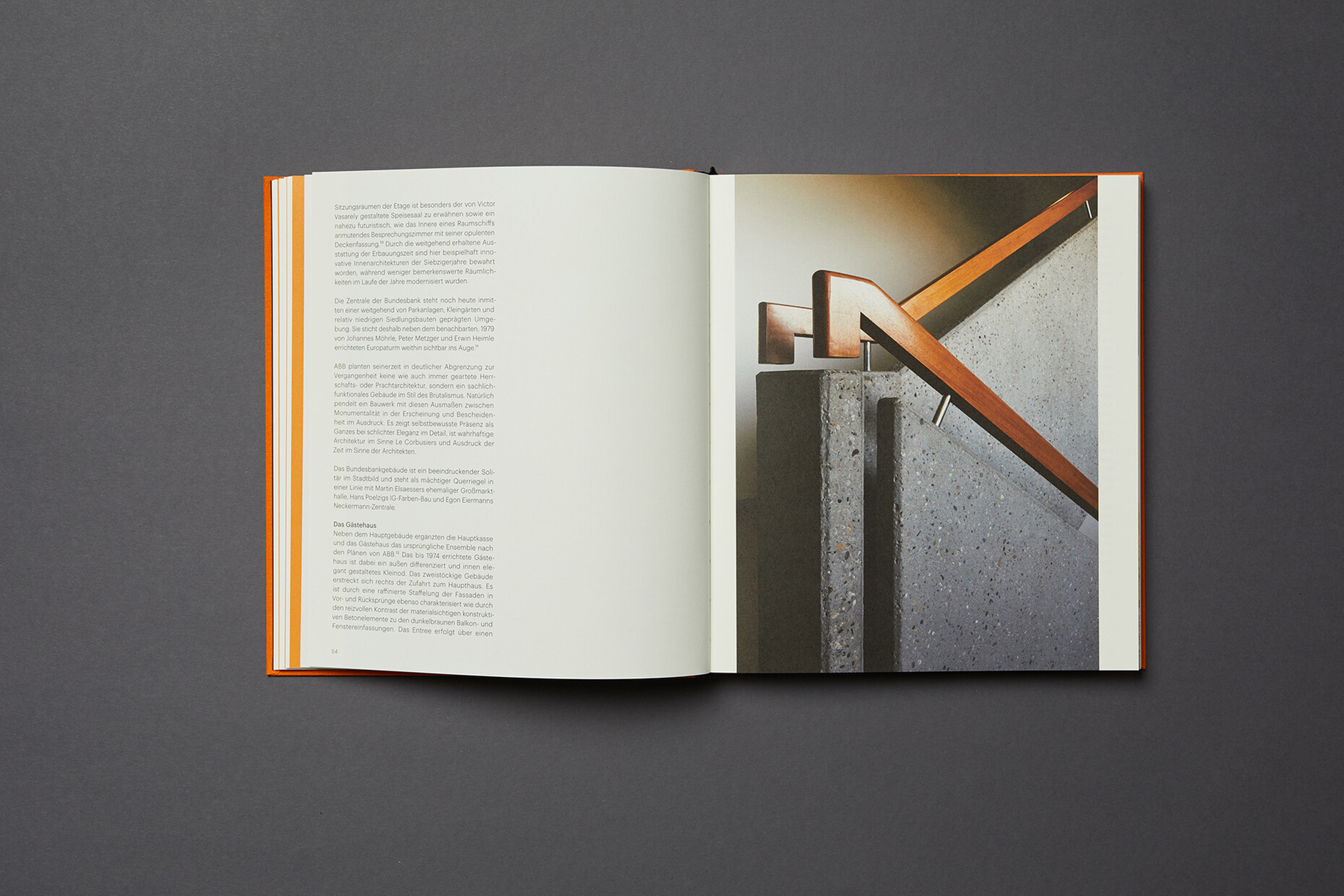

Wilhelm Opatz: There is a photograph in the Bundesbank, where you can find a very fine wooden banister next to the rough concrete, polished to a high gloss by many hands.

The publishers of the architectural guides are the Freunde Frankfurts e.V. – do they also provide the financing or do you do a lot yourself?

Wilhelm Opatz: It's quite a challenge. Basically, every book is divided into two parts: The first part of the work consists of communicating with photographers, authors, editing and reviewing. Then comes the financing. I never do this at the same time, because it's sometimes hard to cope when potential sponsors who would be so well suited to the project cancel. I now have a handful of people and companies at my side who support the architecture guide - such as the Schwäbisch Hall Foundation, but also architecture firms, some of whose buildings I don't even show, but who say we love the city and we want to support the idea. The Friends of Frankfurt are co-publishers and support the project, but they are not solely responsible for financing it.

The books are also a documentation, as the city of Frankfurt am Main continues to change rapidly. As it is neither a pure reference book nor a classic ‘coffee table’ book, your target audience is quite diverse. The architectural guides could also be used for literature in schools. Was that the plan from the start?

Wilhelm Opatz: For me as a graphic designer, architecture was characterised by magazines for a long time. I think my open, almost naïve approach, without reverence for big names, is the essence of the series. I draw strength from this and make many decisions from my gut.

Is there a special characteristic of Frankfurt's architecture that you would like to see in future buildings?

Wilhelm Opatz: The special aspects of architecture always require that the clients are on an equal footing with the architects, that they can surprise and convince each other at the same time. It's not about large investment companies that want to construct buildings that are big, wide and powerful. Even in competitions, the clients don't necessarily have their say. The togetherness of those who create the building is important. When this works, the result is imaginative, wonderful architecture that is well thought out and can amaze. The buildings of the investment companies are certainly technically marvellous, but they lack something special, such as a special entrance or an unusual staircase, because the beautiful details often cost a little more effort and money. Architects today are under enormous pressure to function perfectly, as the competition is always waiting for the first mistake. There are no phases of movement, at least that's what I often hear in conversations with them. As a result, they no longer invest beyond the cost estimate. What also strikes me is that architects today no longer look back. They build for the present and the future. They no longer build for the ‘second glance’ and for nostalgia.

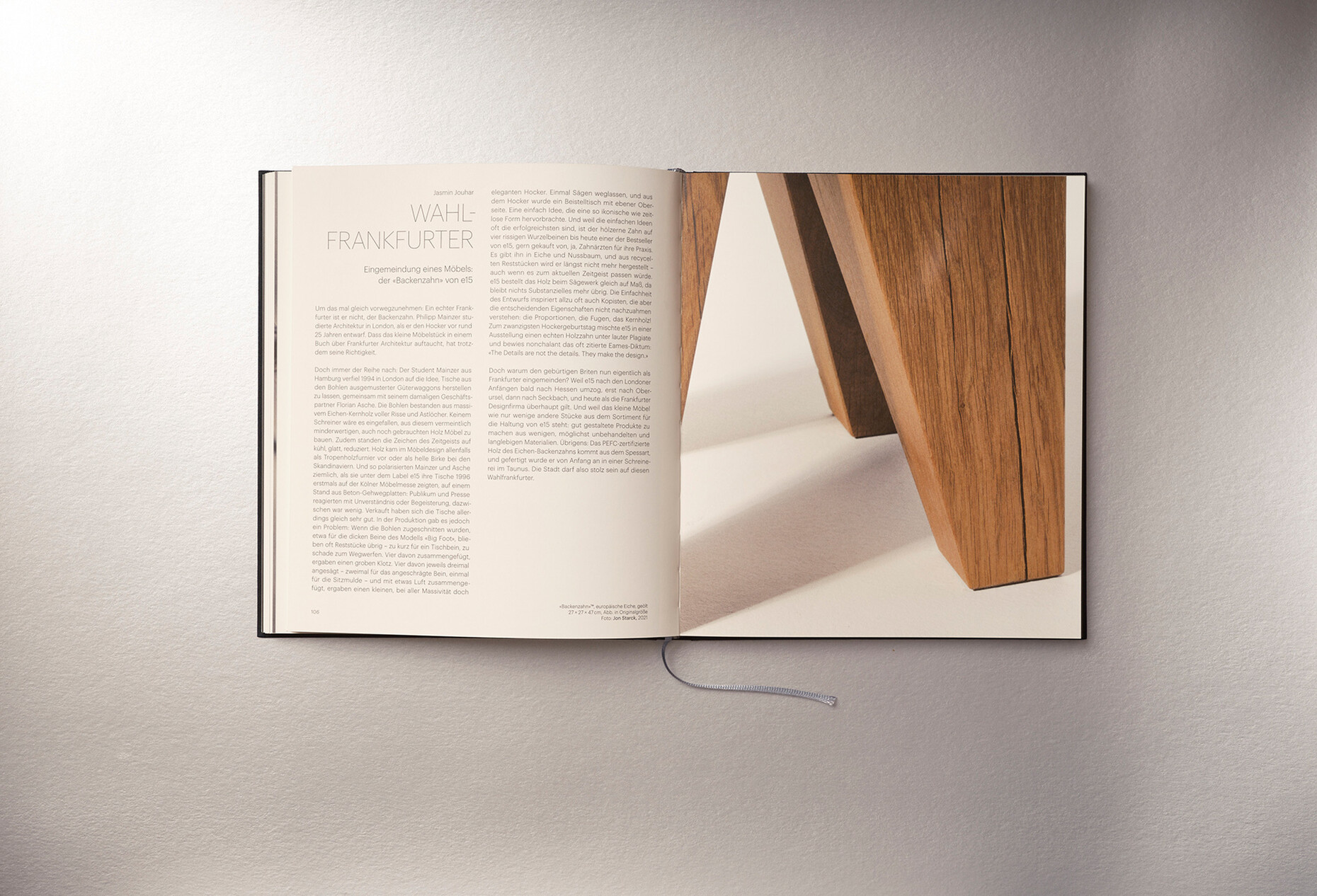

In addition to the buildings, the 90s book also presents the "Backenzahn" from e15. Why did you choose it?

Wilhelm Opatz: It shaped the decade, just like the T-shirts by artist Carsten Fock. They are simply part of it, after all, architects also have a life and work alongside their time in the office. I'm a little annoyed that I didn't realise this earlier. The side paths next to the main route and the stories associated with them are important.

The bonus buildings are an "extra" in the books, like the bonus tracks on a CD. What character do they have?

Wilhelm Opatz: The bonus buildings are a freestyle. Buildings that became interesting at second glance. In the meantime, they are basically on the same level as the ten buildings that are presented in detail in advance. One example is the conversion of a roadside kiosk that I used to drive past every day. At some point, I was intrigued to find out why the conversion had taken place. I have perhaps also become braver and freer today than I was in the first volumes.

What can we expect in the Architectural Guide 2000 – 2009?

Wilhelm Opatz: In addition to the famous buildings such as the Mainplaza (high-rise on the Deutschherrnufer, by Kollhoff Architekten), there are also discoveries – such as a hidden school by Claude Costantini and Michel Regembal.

Did anything surprise you during your research?

Wilhelm Opatz: Dealing with the buildings and the architects themselves. The fact that this current architecture is seen by them as the optimum and therefore there is a certain pressure on me to include their work in the selection. As we enter the 2000s, the nostalgia and documentation for history is over, now it's about the present and therefore also about exerting influence.

Are you impressed by that?

Wilhelm Opatz: Not an issue. Of course, I make it difficult for myself, because if every architectural firm mentioned paid a certain amount for the publication, it would be financed more quickly. But I don't follow that model. The architecture guides should be and remain authentic. It's about my view and that of the photographers, it's about heroes and anti-heroes. I see myself as a curator. If you allow your selection to be determined by financial means, you are a contractor, not a curator.

Is there a building on your list that you would still like to explore?

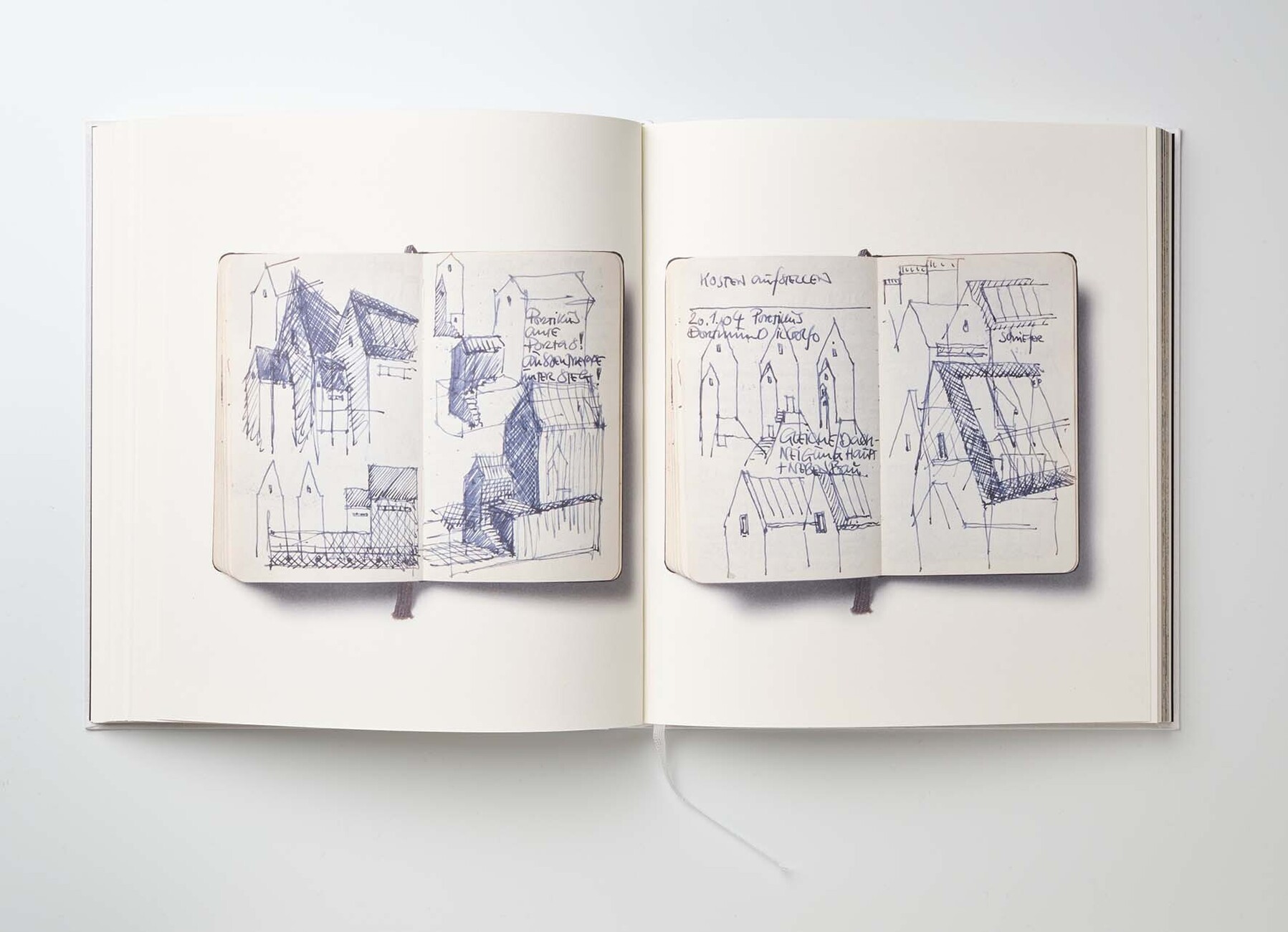

Wilhelm Opatz: There is an exciting building for a data centre from the 2010s that will probably be difficult to explore. And at the well-known Portikus, the curators unfortunately didn't take my enquiry seriously and I wasn't granted access for our project. Now I'm doing it differently: instead of showing the building, I'm showing sketches by Prof Mäckler himself.

You have found a side path.

Wilhelm Opatz: Exactly. And that makes an initially negative experience positive. And in the end, the architect's personal notes are even more exciting than a photo of the building, which is very well known. Of course, this persistence takes time. But I don't give up.

Could you also imagine researching architecture guides for another city?

Wilhelm Opatz: No. The books live from my local knowledge and from the coincidences that arise when you live in the city itself, such as through conversations or mentions in the local newspaper. I also have no aversion to unpopular neighbourhoods such as Rödelheim, Fechenheim or Westhausen. In order to be able to maintain the personal touch of the architectural guides for other cities, I would need a partner – franchising is the magic word.

What kind of message do you want to convey to readers with the architecture guides?

Wilhelm Opatz: Open your eyes. See what architecture can be discovered in your neighbourhood. Take a different route home from time to time, be curious. That's what I try to give people with my snapshots.

Architekturführer Frankfurt 2000–2009

Published by Wilhelm E. Opatz, Friends of Frankfurt

Junius Publishing House

208 pages, 115 colour illustrations

Language: German

ISBN: 9783960605911

48 Euro