Hard shell, soft core

Things are happening in London: After the boroughs had to completely stop their construction activities in the area of affordable housing at the beginning of the 1980s, more and more projects are now being realized that follow a social agenda. Examples of this are the boroughs of Hackney and Brent with their housing programs, which have included architecturally ambitious projects such as Aikin Terrace by Stephen Taylor Architects and Ely Court by Alison Brooks Architects. A new addition is the "House For Artists" in the Barking and Dagenham district – a five-story building with living space for twelve artists, which also houses studios and a community room on a total of 1553 square meters. Behind the project is Create London, an arts organization that aims to realize social and cultural infrastructures in collaboration with creative people and the neighborhood. Art and culture are thus to be implemented as part of public life in the respective boroughs, which is why Create London collaborated in advance with the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham, which partially financed the project.

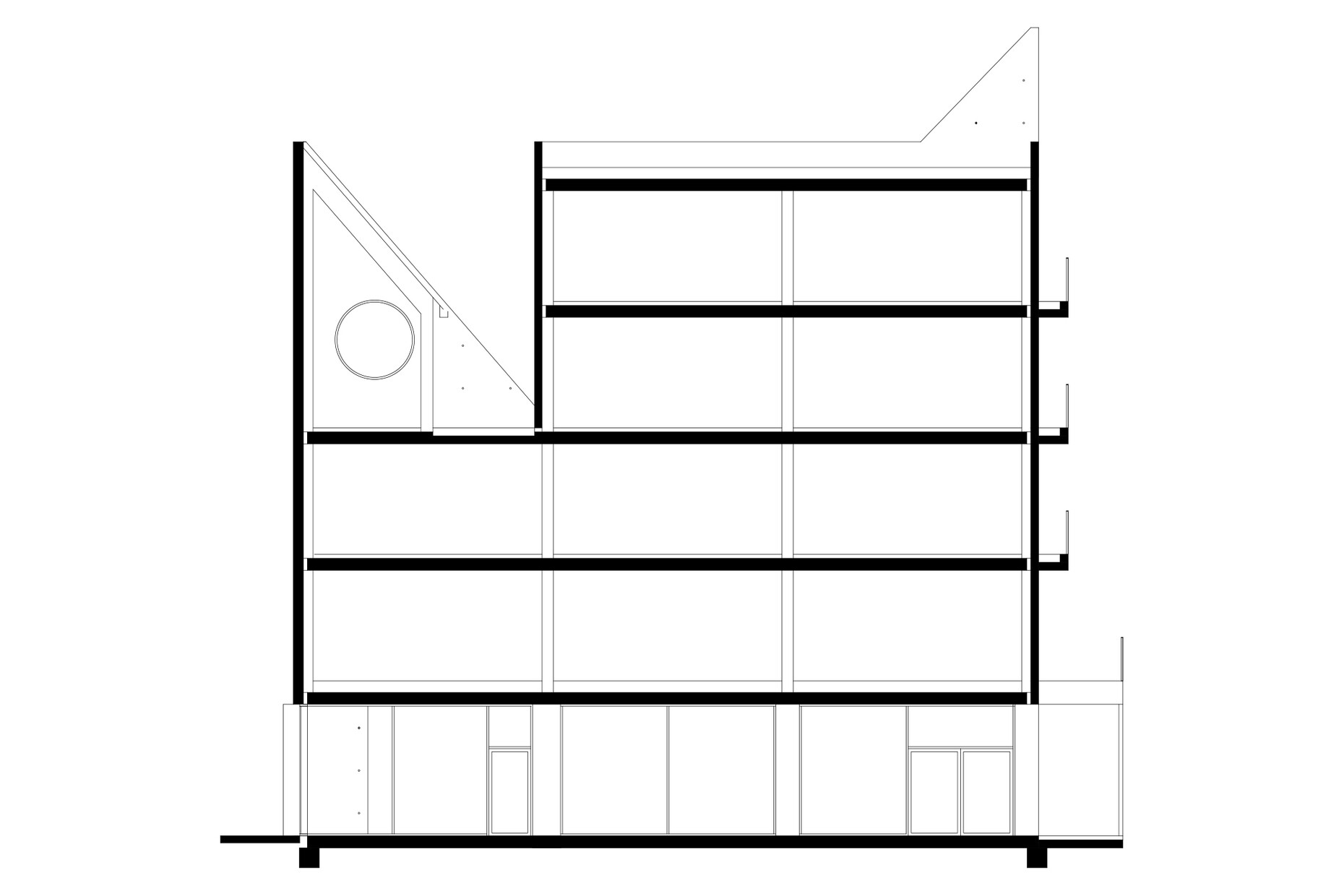

Following a competition won by the young London-based architecture firm Apparata in 2016, the "House For Artists" was finally completed in 2021. "This new architectural marker in Barking & Dagenham makes visible the council's commitment to support long-term accessible arts programmes for its local community," Diana Ibáñez López, senior curator at Create London, says of the project. However, the location is not an easy one: for example, according to the homepage of the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham, the borough, located in the northeast, had the highest "IMD score" (indices of multiple deprivation) in London in 2019, a dataset used to measure social deprivation. And in terms of urban design, the surrounding area also has a heterogeneous structure with rows of flats, residential towers, terraced houses and housing estates that seem to clash incoherently. A multi-lane road in the north, south and west surrounds the area. In addition, there are the above-ground tracks of the subway to the east. Apparata responded to this situation with a robust urban building block – a neo-brutalist building that attempts to dock with the existing structure through the geometry of its sculpturally shaped concrete façade. The generously glazed studios on the first floor, which also include a flexibly playable public community space, have an effect on the urban space and are thus intended to connect with the neighborhood.

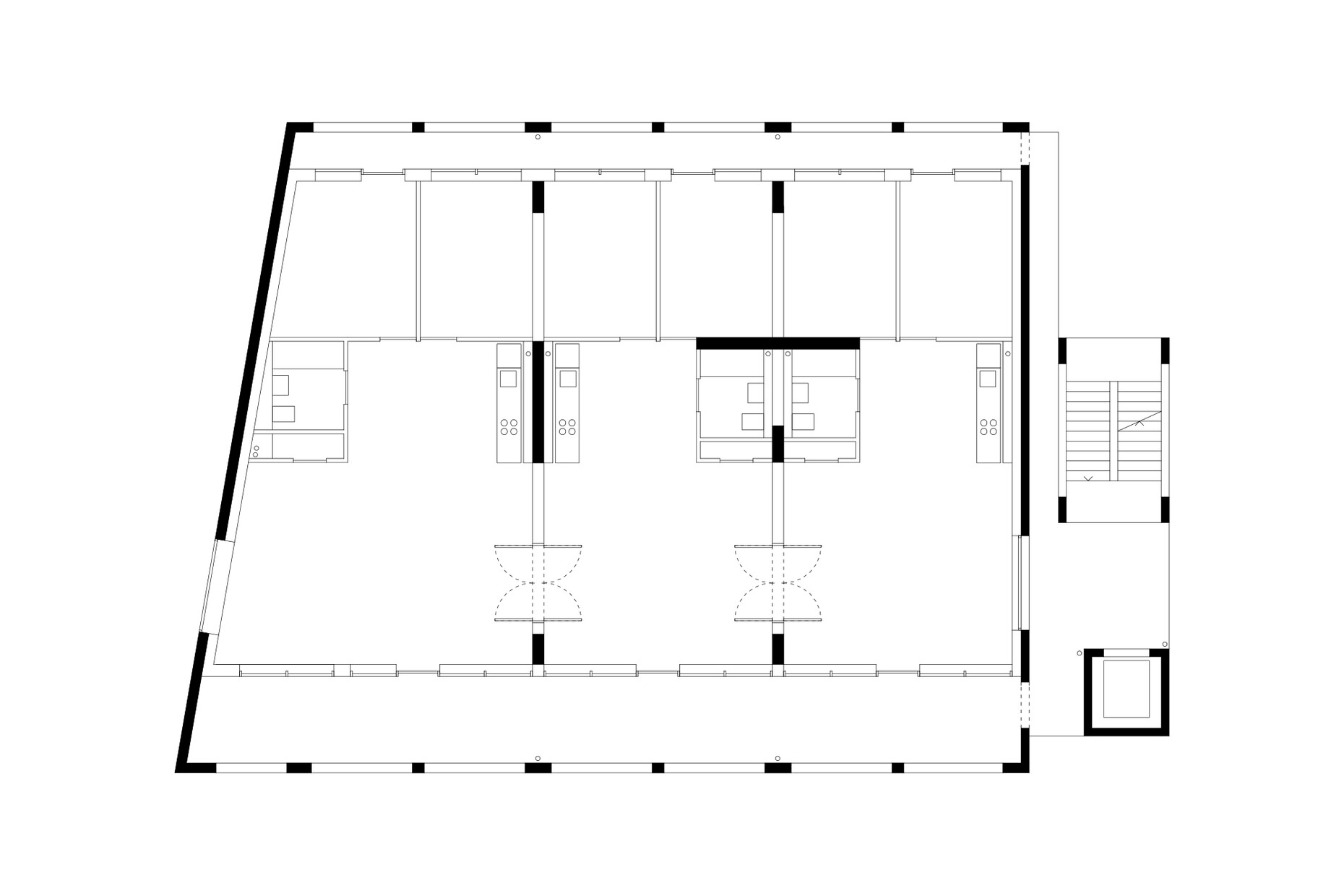

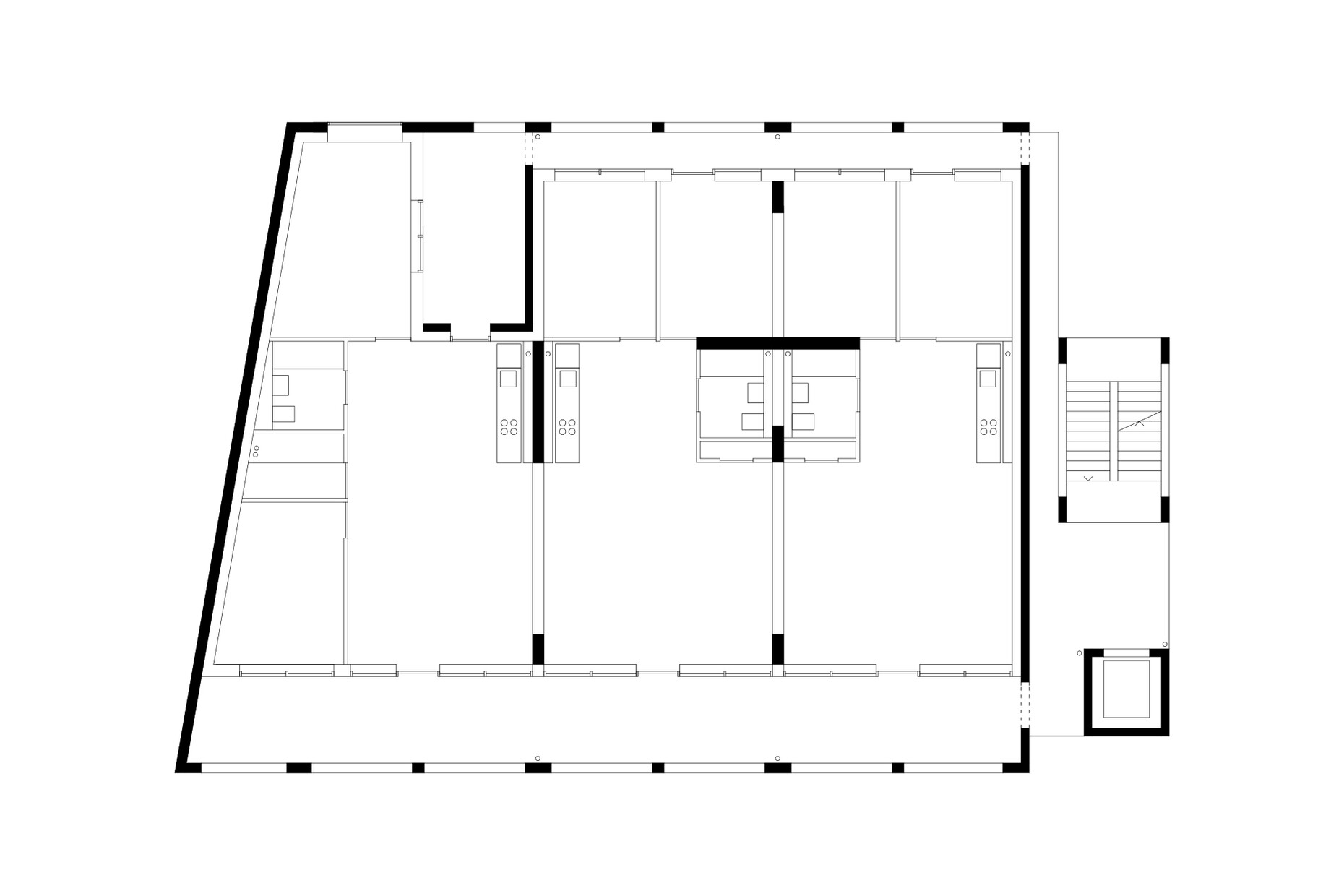

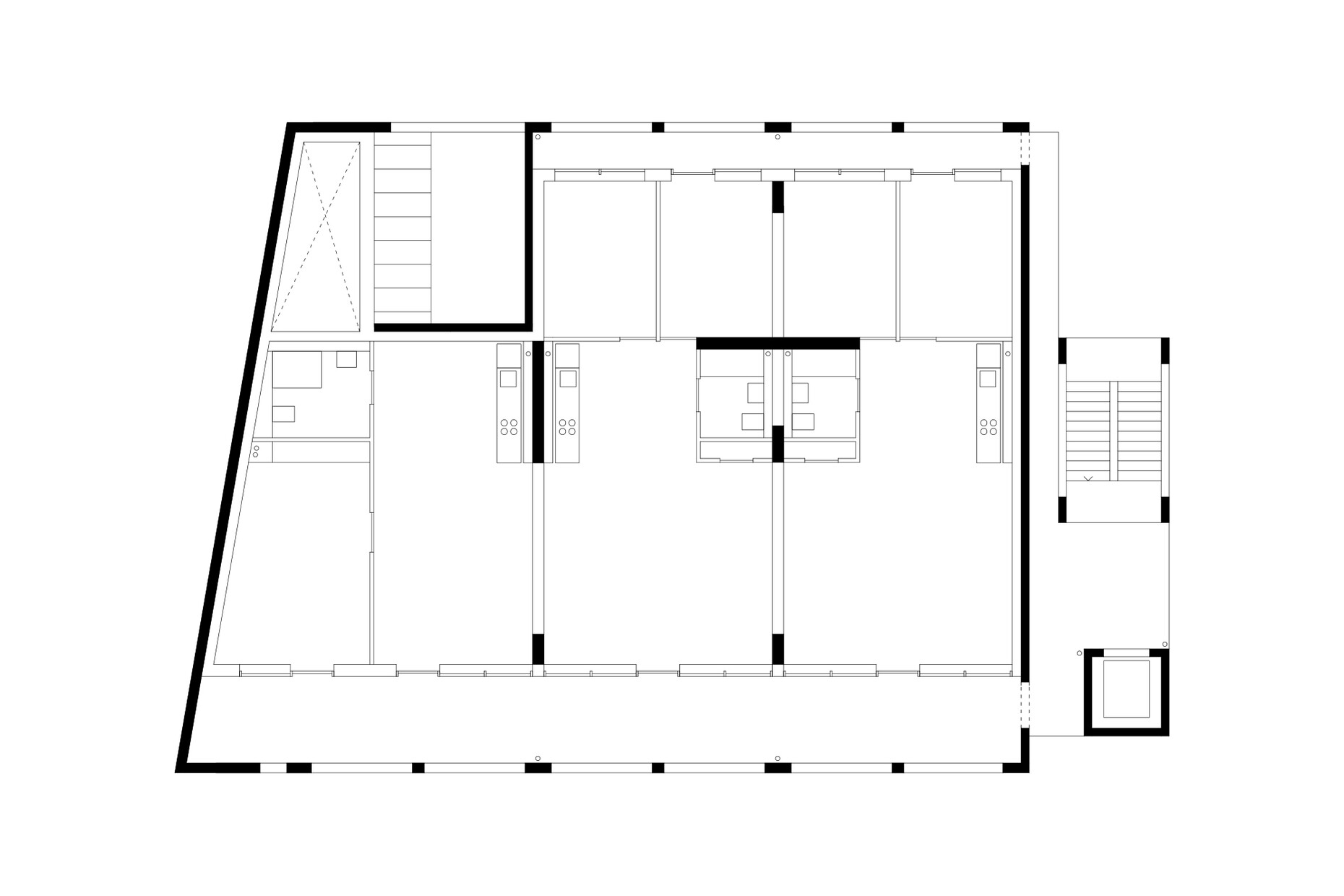

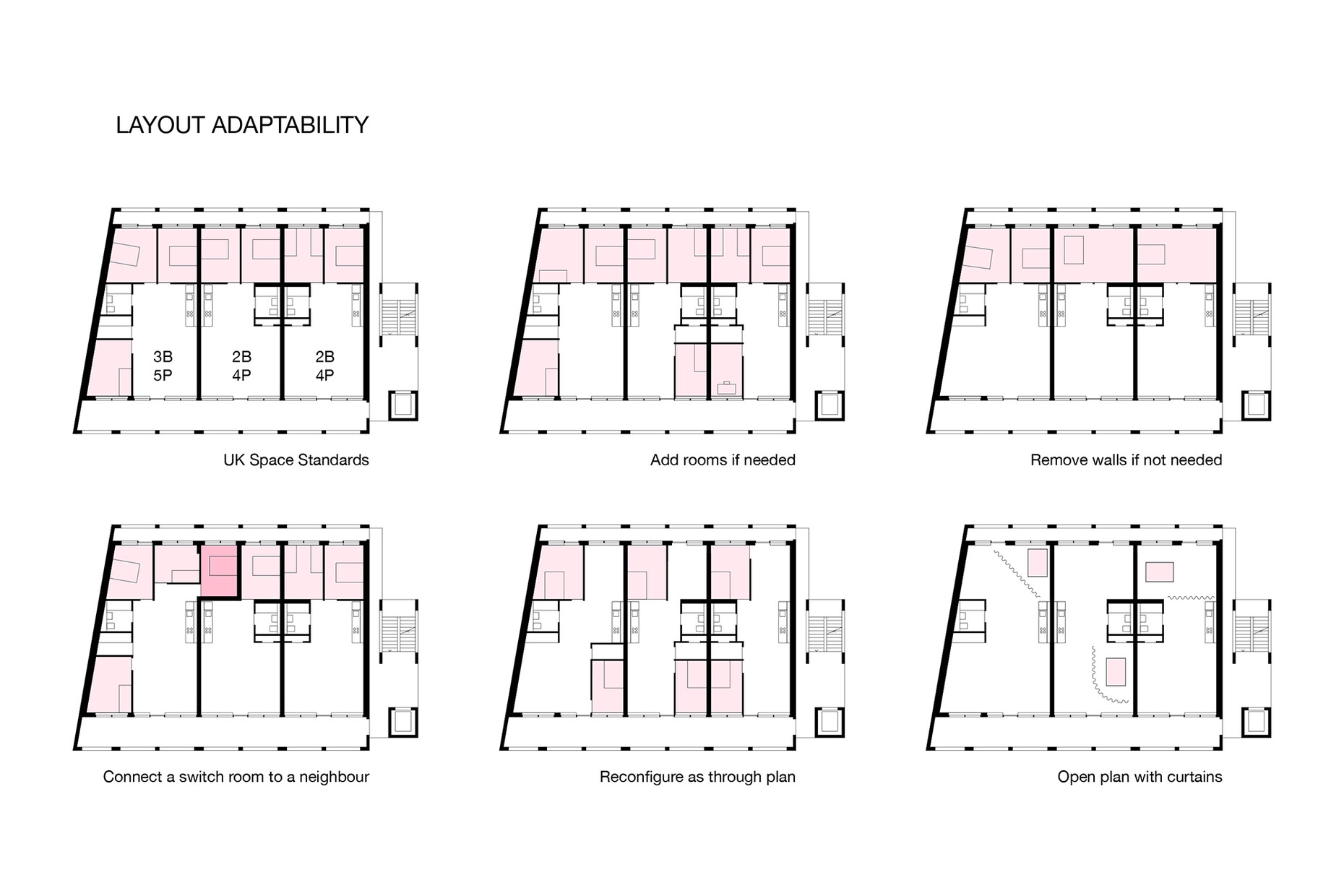

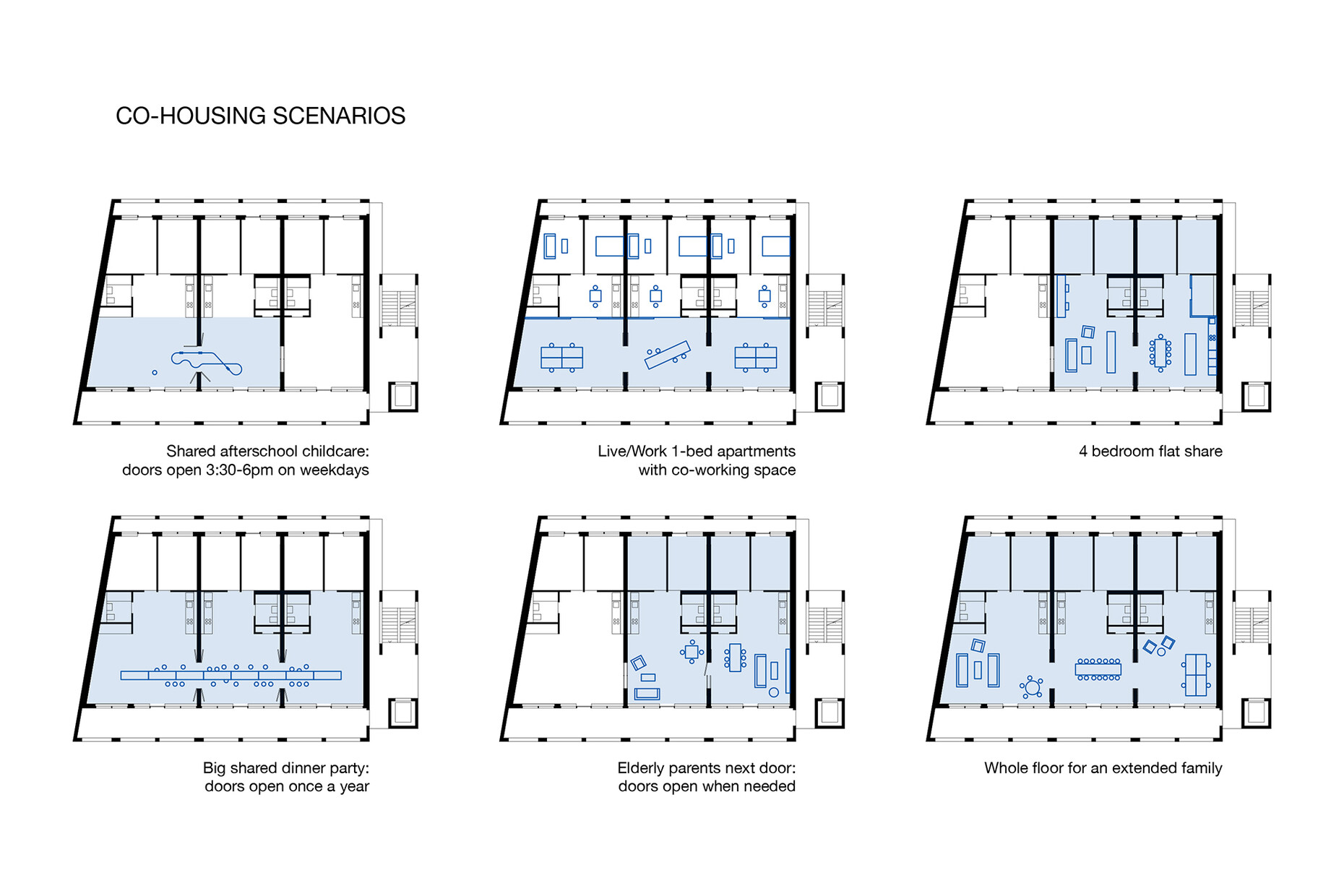

The upper four floors are reached via an access core with a two-flight staircase and an elevator that docks with the building in the northeast. From there, access is gained to an arcade in the southeast, which leads to the respective apartments and also serves as a communal zone. A sense of community is also inscribed in the living spaces, as Astrid Smitham, partner at Apparata, explains: "Contemporary apartment design is still largely based on the nuclear family when this model doesn’t reflect the diverse configuration of people’s lives today. New kinds of arrangements are needed: the possibility of an elderly parent to live with you temporarily, to share childcare with another household, or to grow a meaningful connection with neighbours." The individual units are designed to be correspondingly flexible, providing a kind of soft core within the monolithic building, and can be zoned in a variety of ways through double doors in the apartment partitions. The bedrooms are located on the northwest side and open onto a narrow continuous balcony, while the kitchen and bathroom are located in the center of each apartment.

In terms of design, the brutalist aesthetic of the building refers to British post-war architecture with its social buildings, which is why it can also be read as a reference to a welfare state that came to an end in the Thatcher era. From an ecological point of view, however, the monolithic concrete façade also points to the past, which is why the architects made an effort to at least partially focus on sustainability during construction. For example, 50 percent of the cement is made from a by-product of the steel industry. In addition, the formwork was made from reusable standard parts. And at least the building exceeds British standards by having over 20 percent less embodied carbon than the 2030 climate target set by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and the Greater London Authority (GLA). The extent to which the "House For Artists" will then also be a building of the future in social terms remains to be seen.