Down into Dante's underworld

One of the most exciting projects has been underway in Naples for around 30 years. It brings together contemporary art theory, urban planning, architecture, and art. As artistic coordinator for the city administration of Naples, Achille Bonito Oliva heads the Stazioni dell’Arte (Art Stations) project, which has the lofty goal of transforming the local public transport system into a kind of urban museum for contemporary art.

As a reminder, Bonito Oliva, born in 1939 in Caggiano, in the province of Salerno, is considered one of the most influential art historians and critics of the Italian postwar period. Influenced by profound interdisciplinarity, his path took him from Salerno to law and literature studies and from there to the avant-garde literary movement Gruppo 63. From 1968 onwards, he influenced generations of students as professor of contemporary art history at La Sapienza University in Rome. At a time when minimal art and conceptual art were setting the tone, Bonito Oliva proclaimed a return to figuration, myth, and artisanal subjectivity in 1979: the introduction of the term Transavanguardia (Transavantgarde) can be considered perhaps Bonito Oliva's most important contribution to contemporary art discourse.

In response to what he perceived as the sterile abstraction of the 1970s, Bonito Oliva argued that art had reached a “dead end” and could no longer develop in a linear fashion. Instead, he called for “cultural nomadism,” which would allow artists to move freely between different eras, styles, and traditions. Transavantgarde artists therefore reject the “hysteria for the new” and instead draw on styles of the past to recombine them in new ways. A central motif in this theory is the metaphor of the “seeing blind”: Transavantgarde artists shatter the lens that enables a uniform view of the world and instead look around with a fragmentary, kaleidoscopic perception – as “nihilistic” artists in the Nietzschean sense, freed from traditional references and in constant motion instead of striving toward a fixed goal.

Of obligatory museums and oversized toilets

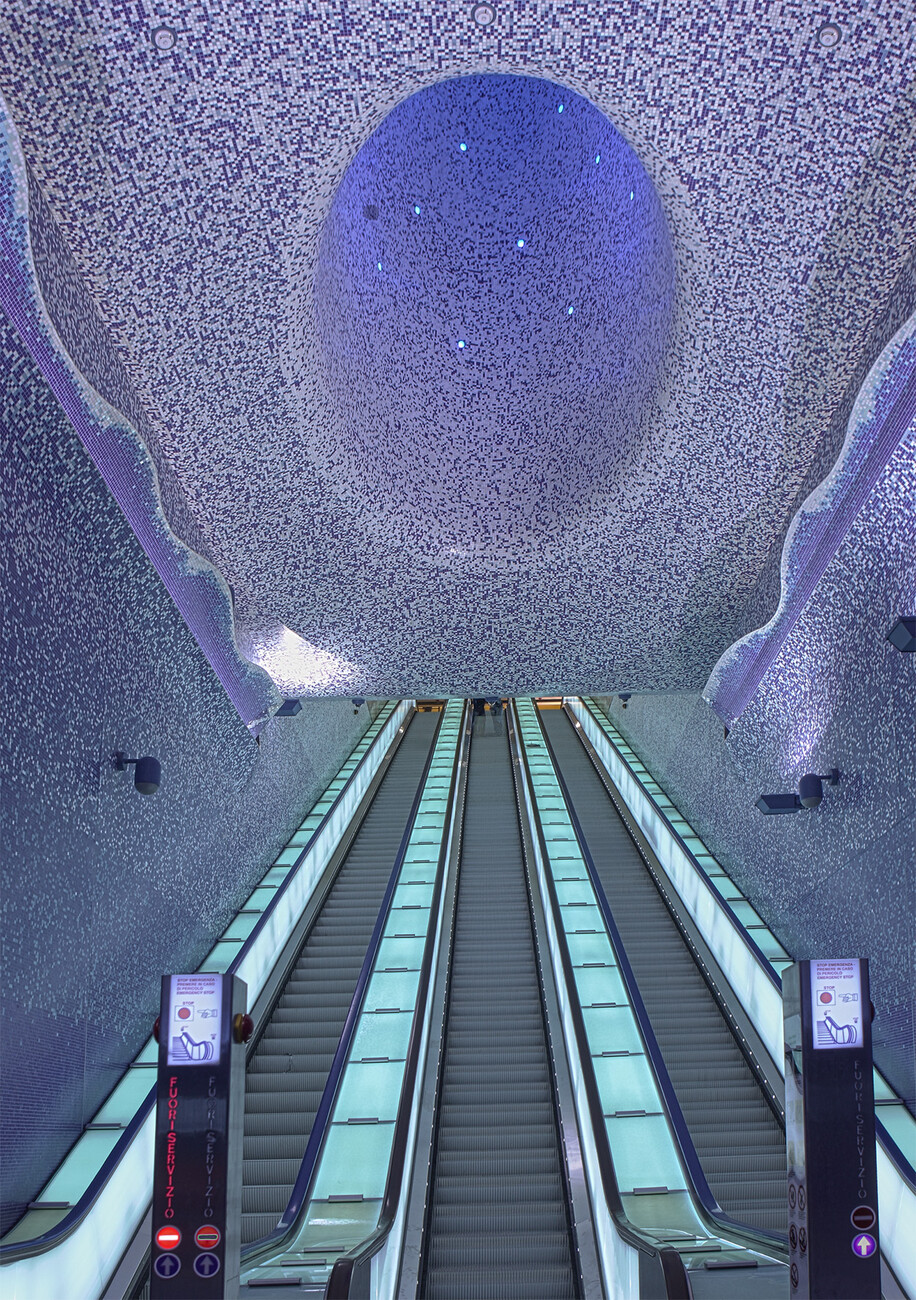

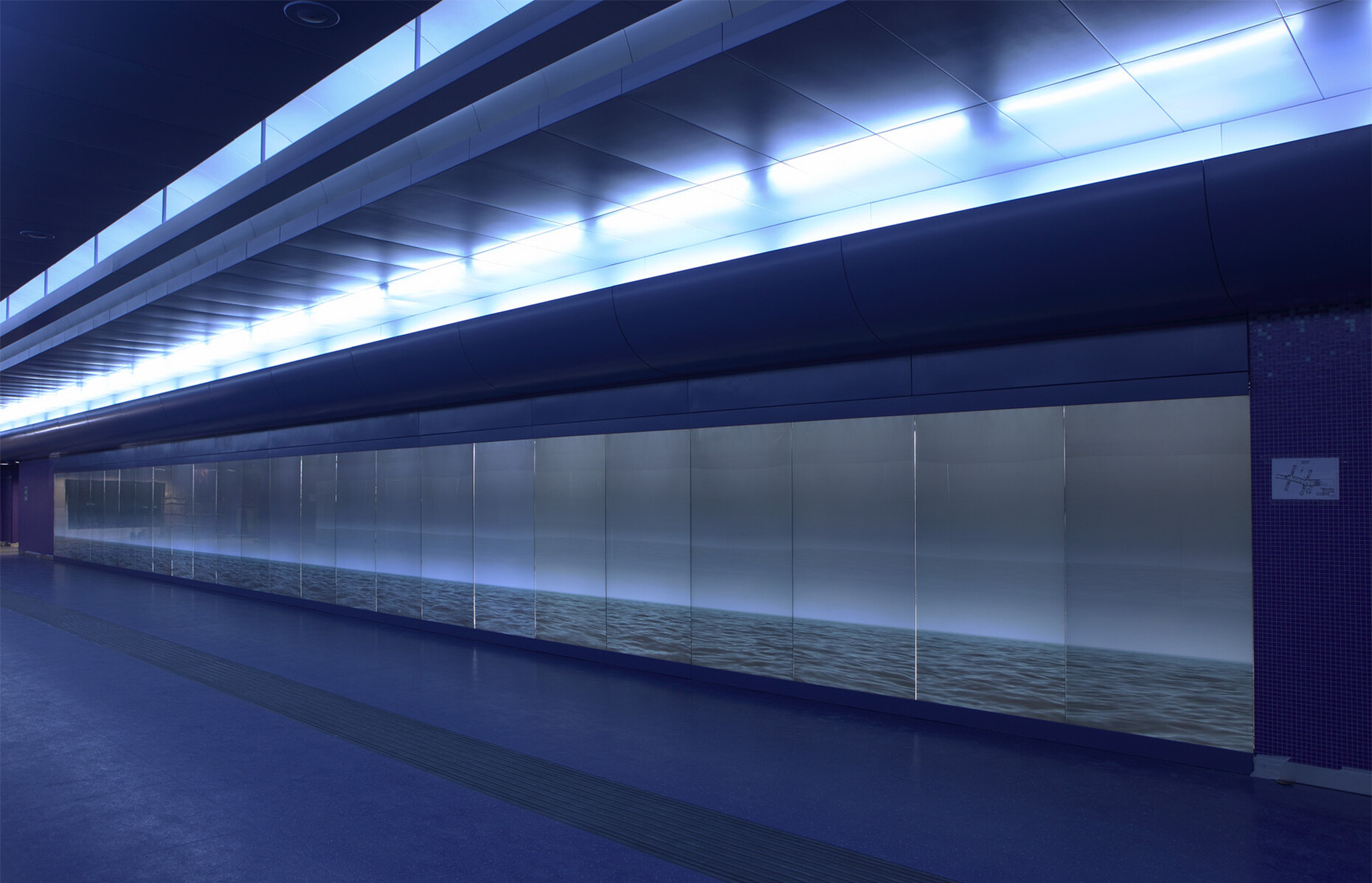

After artistically directing the 45th Venice Biennale in 1993, Achille Bonito Oliva was able to extend his idea of the “Museo Obbligatorio” (obligatory museum) to urban space. In the “Museo Obbligatorio,” art no longer takes place only in closed institutions, but encounters citizens in their everyday lives. In a subway station, according to the thesis, passengers cannot help but notice the works of art as they move through the space. In this way, the anonymity and homogeneity of modern transit spaces could be broken up and instead enriched with identity and beauty. Where conventional metro stations often resemble “oversized toilets” with tiles and poor lighting, which can be demoralizing for commuters, an “osmosis” between architecture and art could take place, improving the quality of life physically, morally, and intellectually.

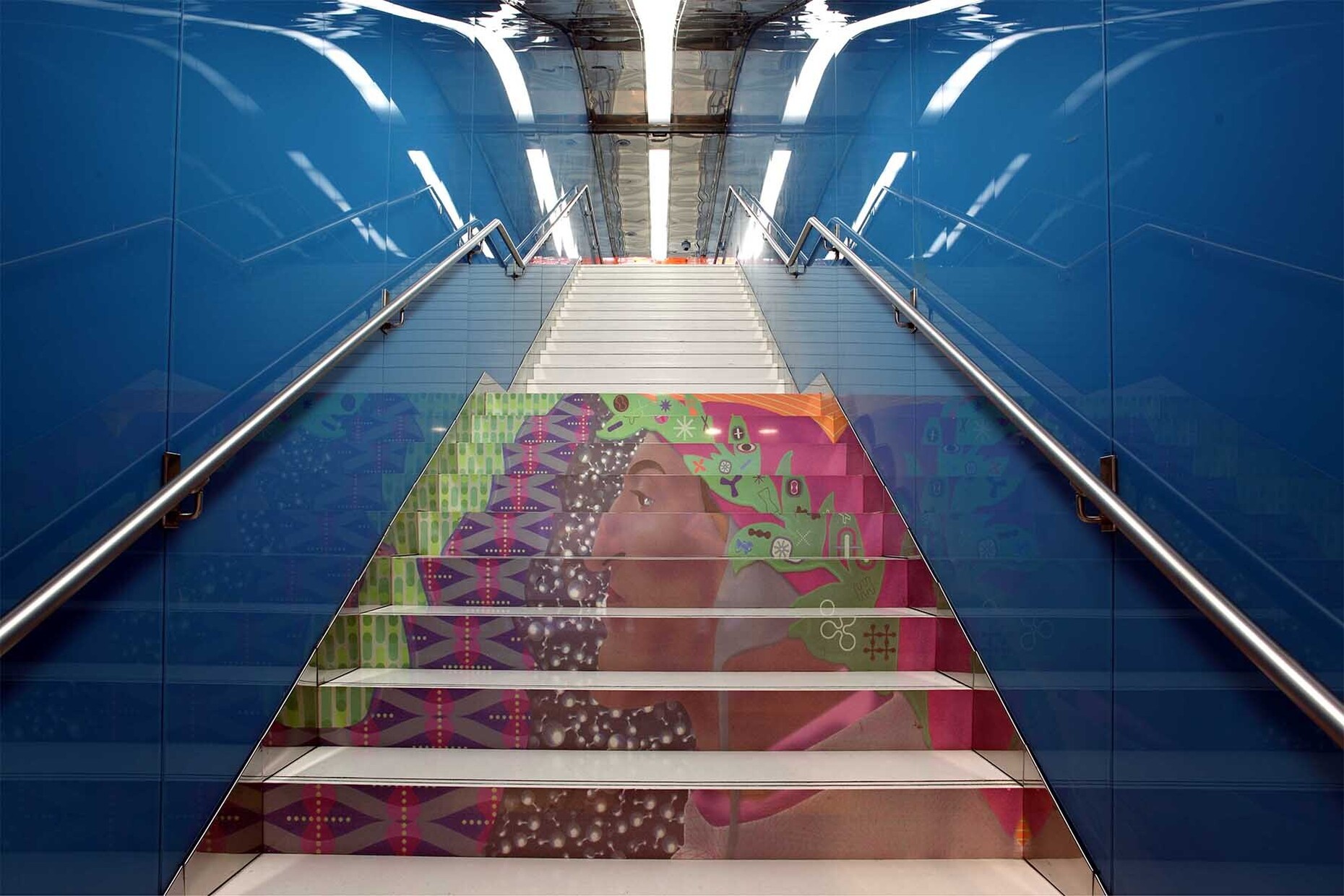

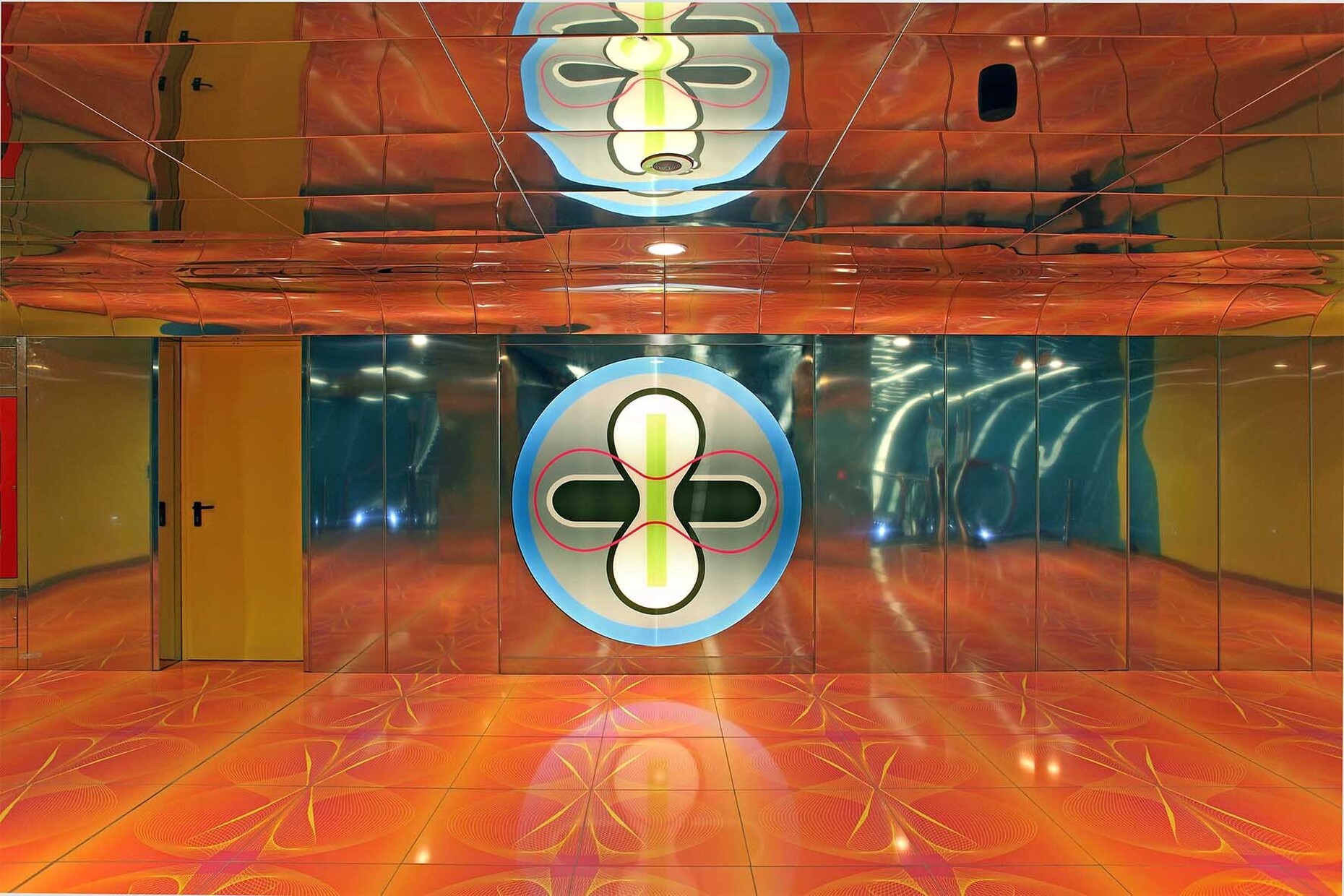

Since 1993, under the direction of Bonito Oliva, numerous works of art by over 80 renowned international artists have become part of the Neapolitan metro system. Bonito Oliva coordinated the collaboration between them and the architects involved, including such luminaries as Álvaro Siza, Gae Aulenti, Alessandro Mendini, Dominique Perrault, and Karim Rashid. Each station follows its own logic, often influenced by the specific history of the location. The Università station, designed by Karim Rashid, for example, translates questions of knowledge and language in the digital age into space and form, while the Duomo station, designed by Massimiliano Fuksas, integrates the archaeological finds of the foundations of a Roman temple from the first century AD and the remains of an ancient gymnasium.

Museum in motion

The Monte Sant'Angelo station on Line 7, designed by Anish Kapoor in collaboration with the architectural office Future Systems (Jan Kaplický and Amanda Levete), was recently opened. Kapoor created two sculptural entrances for it, one of which, made of Corten steel and called La Bocca (The Mouth), is reminiscent of a mixture of an organic throat and a giant croissant. The sculpture seems to suck travelers into the underworld. In this way, the artist references the volcanic landscape of Naples and Dante's Divine Comedy. Inside the station, parts of the tunnel walls were left raw and unfinished to preserve an authenticity appropriate to the location's depth.

By involving international architects and artists, not only functional hubs were created here, but also places with a high quality of life. In neighborhoods such as Scampia or Piscinola, the stations serve as anchor points for new developments and as an expression of new civic pride beyond SSC Napoli, Diego Maradona, and similar folklore. The conversion of parking lots into pedestrian zones—such as the area in front of Villa Pignatelli on the Riviera di Chiaia in front of the San Pasquale station—demonstrates the direct benefits for the city, its people, and social life. As a result, the Naples Metro has become a genuine cultural attraction. Guided tours and educational programs convey knowledge about contemporary art to a broad audience. As a transfer of the theoretical foundations of the Transavantgarde – cultural nomadism and a return to narrative – into urban space, the Neapolitan metro is no longer merely a means of transport, but a “museum in motion” that breaks down the barriers between elitist art and people's everyday lives.