The Power of the Collective

Alexander Russ: Lacol describes itself as a architects' cooperative. What does this mean in concrete terms?

Carles Baiges Camprubí: Lacol is not structured like a classic architecture firm, where there are one or a few bosses and then salaried architects. With us, every employee has the opportunity to be part of a collective, and to have equal rights. We share the responsibility, but also the idea of what we want to build and accomplish as a company.

Why did you choose to work this way?

Carles Baiges Camprubí: We founded Lacol in 2009 when we were students, in order to share space for our student designs. Towards the end of our studies, however, we started working on real projects. The whole thing was a very organic process, strongly influenced by the fact that we wanted to work in a different way than in the various architecture firms where we'd done our internships. There were a lot of cooperatives in our neighbourhood that we interacted with, and that inspired us a great deal. But self-employment was also a way to deal with the economic crisis in Spain at the time. Many fellow students went abroad to find work instead.

How many people now work at Lacol?

Carles Baiges Camprubí: There are twelve employees who belong to the cooperative. In addition, there are six employees who are either students or regular employed architects.

So you actually have architects who aren't part of the cooperative?

Carles Baiges Camprubí: Yes we do, but they can also become part of the cooperative after having worked here for two years.

Is membership optional?

Carles Baiges Camprubí: Yes, it's an option for the employees. They can also decide to continue as employees if they want, but we're obliged to offer them membership in certain conditions.

How does the design process work at Lacol?

Carles Baiges Camprubí: Individual projects are always supervised by one or two project managers. We have regular meetings where the various projects and their progress are presented to the whole team. Everyone can get involved and have some input. In addition, although we're architects, many of us have also completed postgraduate studies. For example, one of my colleagues is a structural engineer, another specialises in the restoration of old buildings, and I'm a sociologist. So I don't design buildings, but instead take care of the communicative and participatory processes or develop various studies.

Your portfolio includes many residential buildings that have a social agenda. How did this come about?

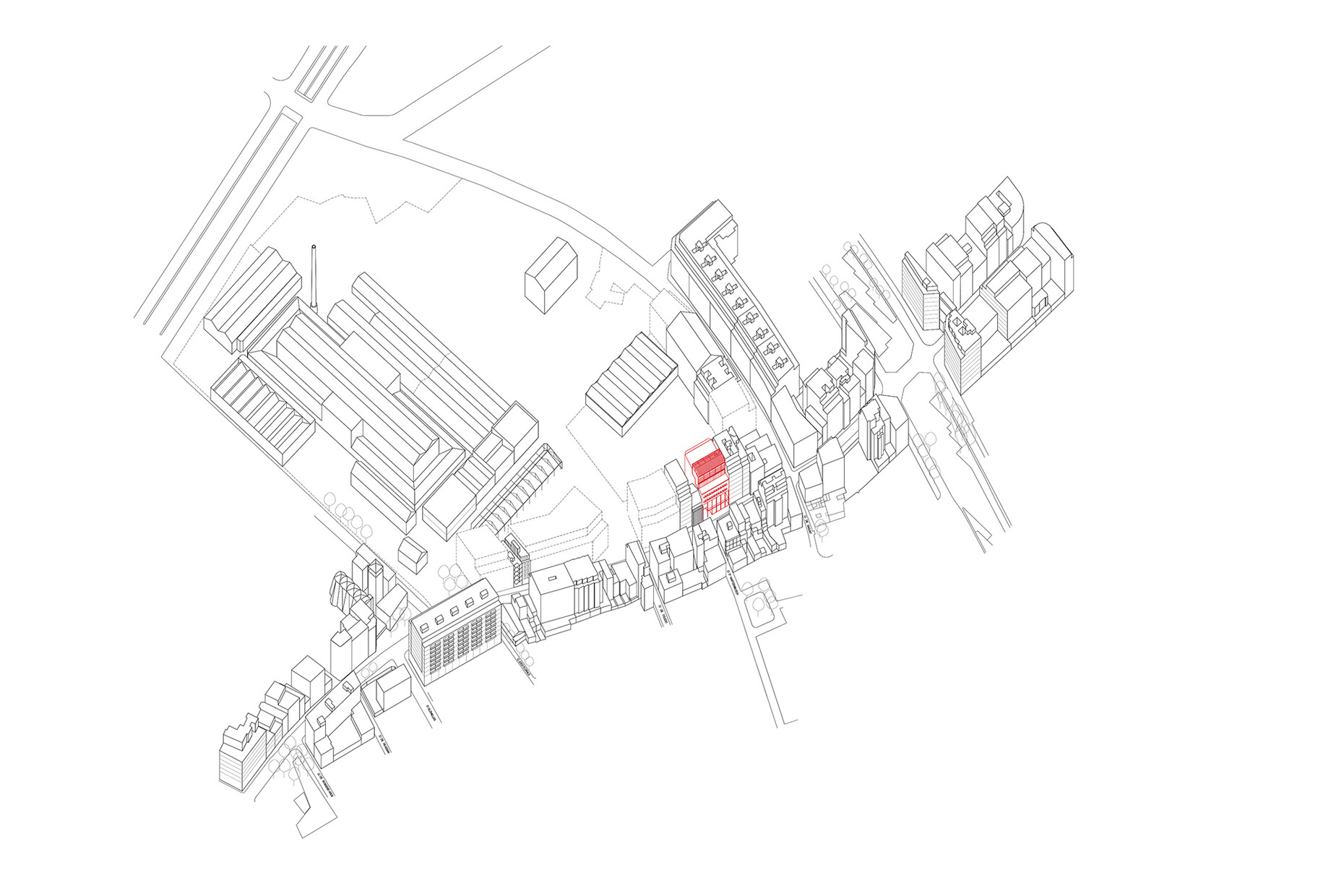

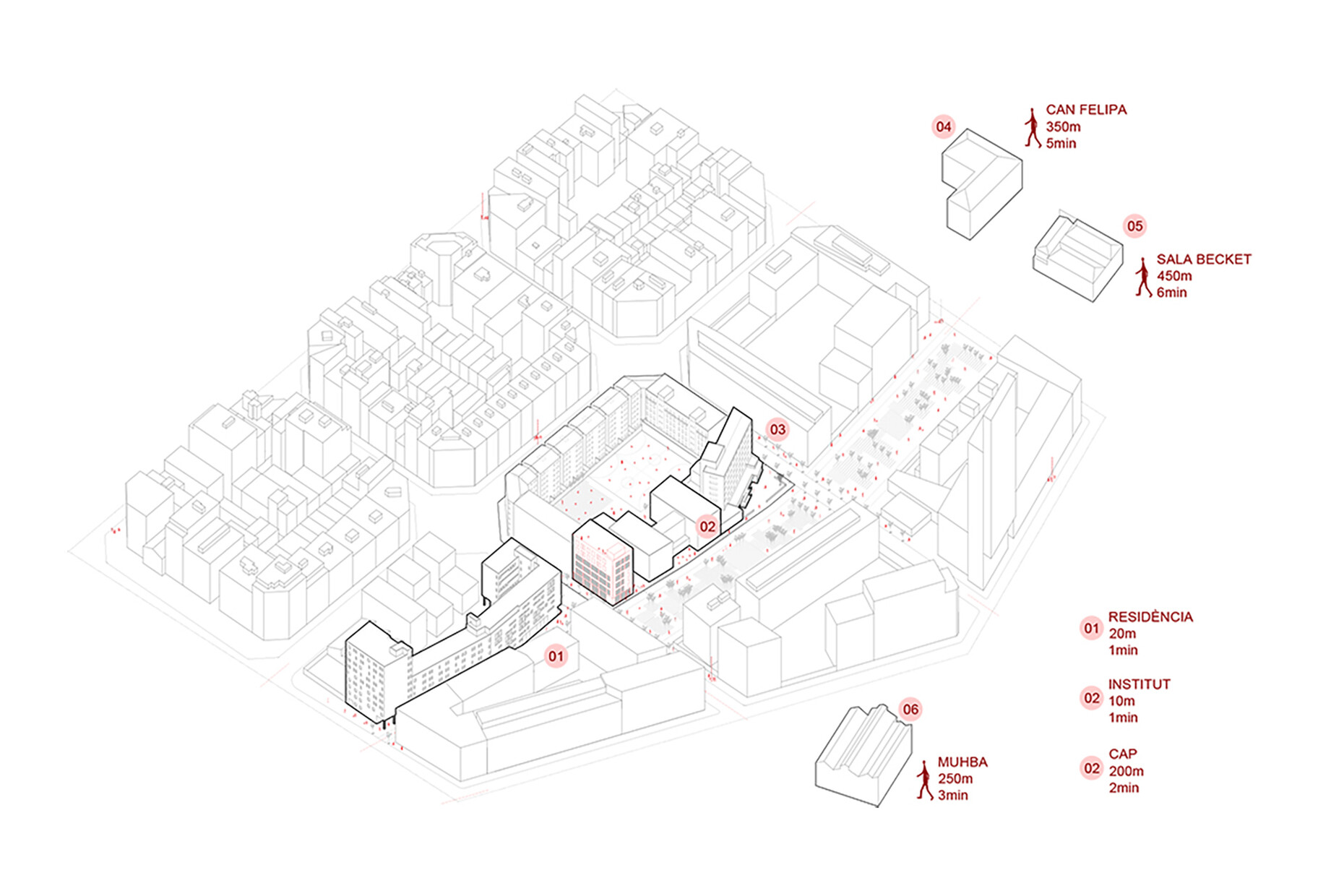

Carles Baiges Camprubí: We feel very comfortable in this area – especially because these projects are based on an approach that suits us very well. One of the things we've done from the beginning is designing for the community and working with participatory processes. A good example is the cooperative housing buildings we've already designed, La Borda and La Balma. But we also renovated a building on which we worked very intensively with the city council, and which will be used as a youth centre. In principle, we take a very proactive approach. For example, we work with a cooperative to find a building site or take care of the financing model. We don't wait for someone to commission us, but jump in and develop the project together with the respective client as early as possible.

La Borda was your first built project. Can you tell us more about the whole process?

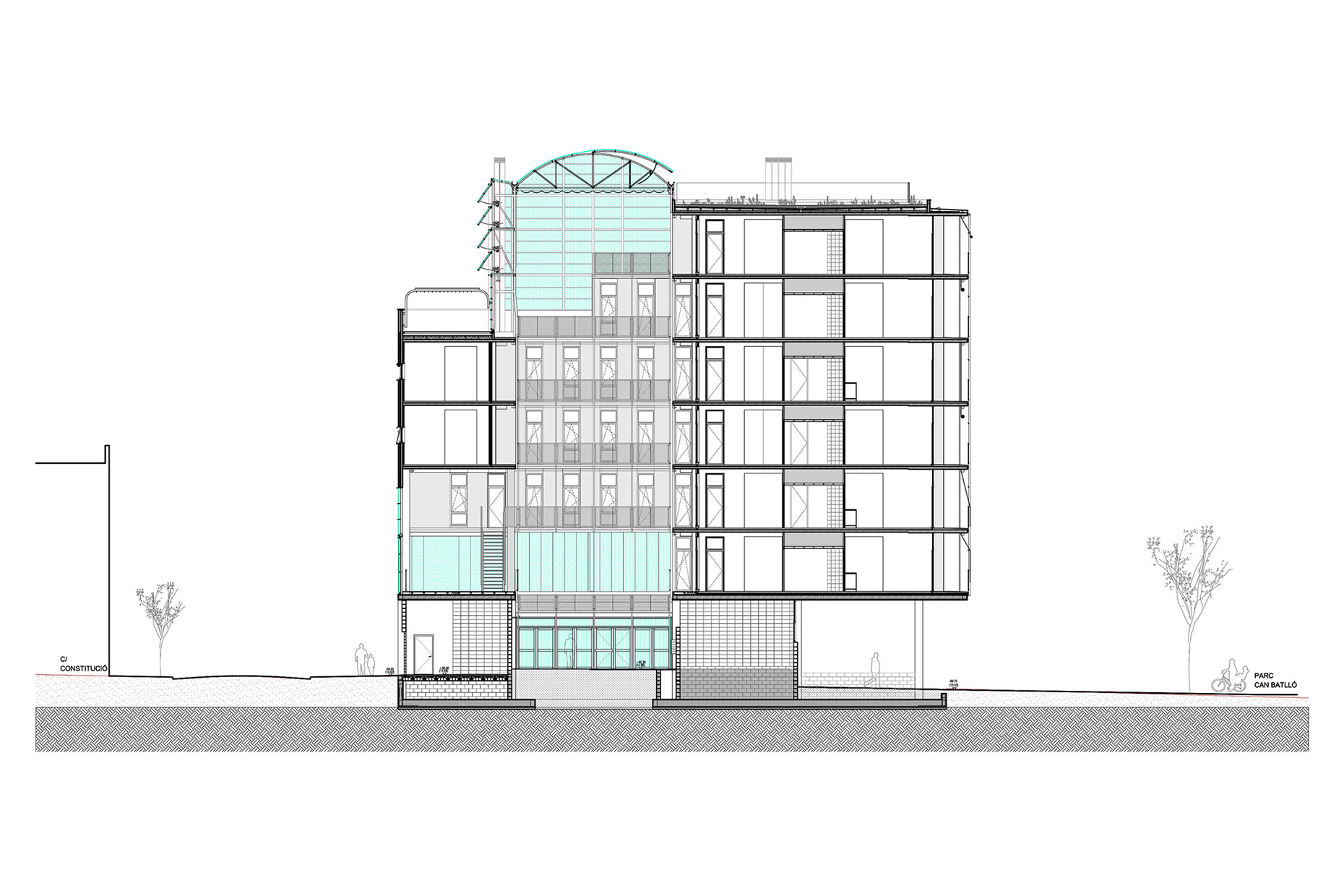

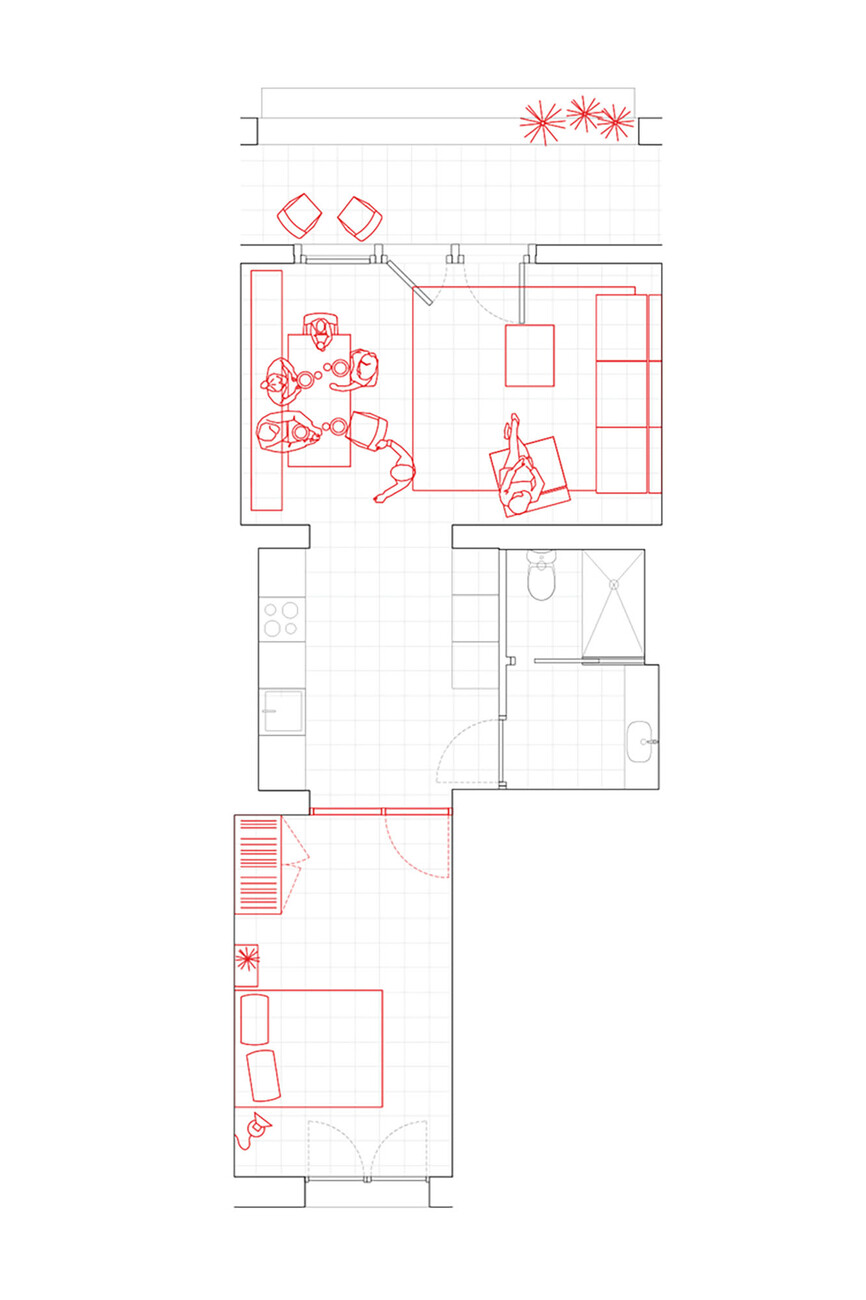

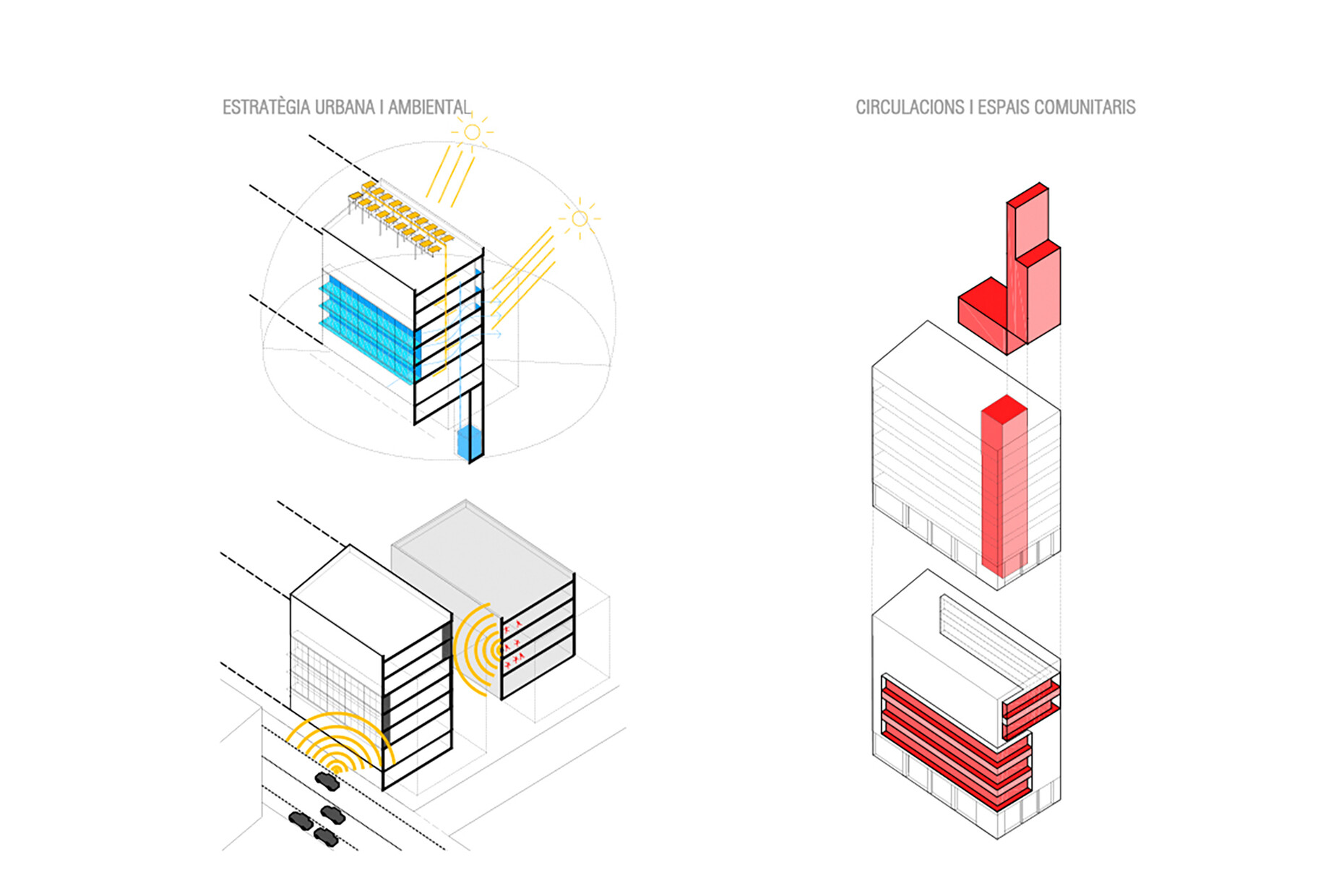

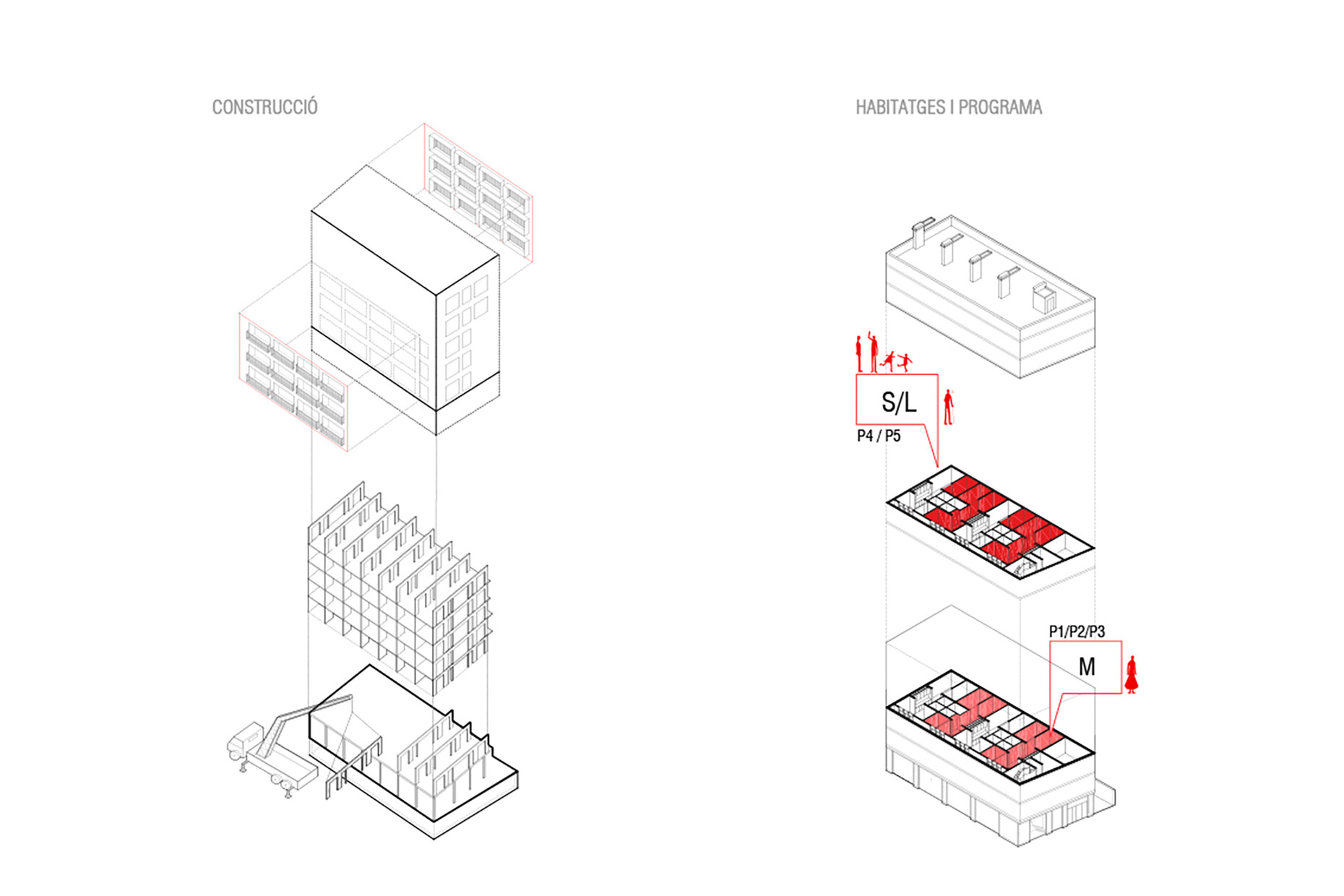

Carles Baiges Camprubí: La Borda is a special project in that some of Lacol's colleagues also later became tenants. The aim was to build as cost-effectively as possible while offering sustainable social housing that also offered communal space. Because we were both the client and the architect, we were able to be very close to the whole process. In this respect, La Borda was the basis for later projects such as La Balma and La Comunal. However, La Borda also has special construction features, which is due to our sustainability agenda. For example, at the time of its construction, the building was the largest timber-constructed residential building in all of Spain.

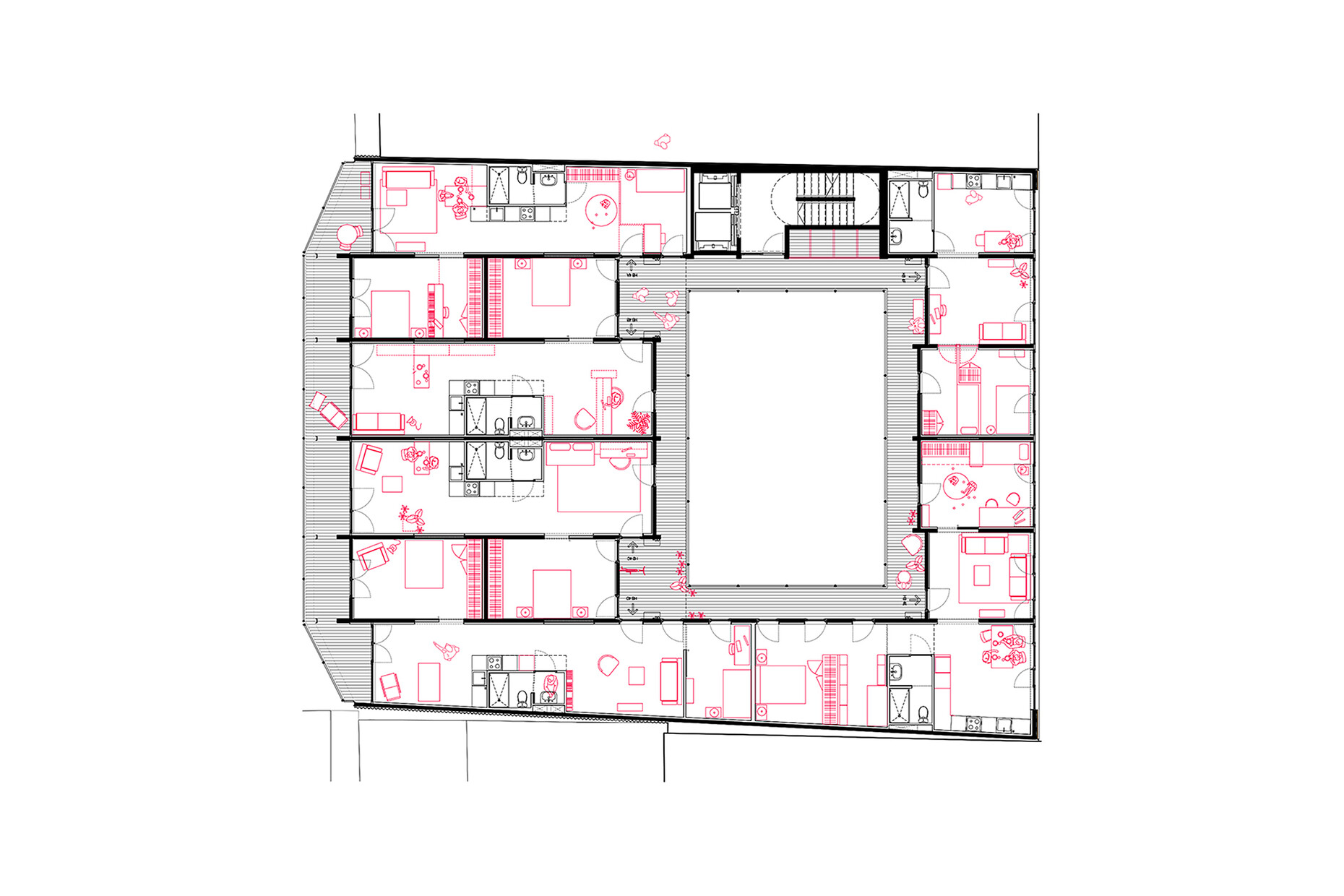

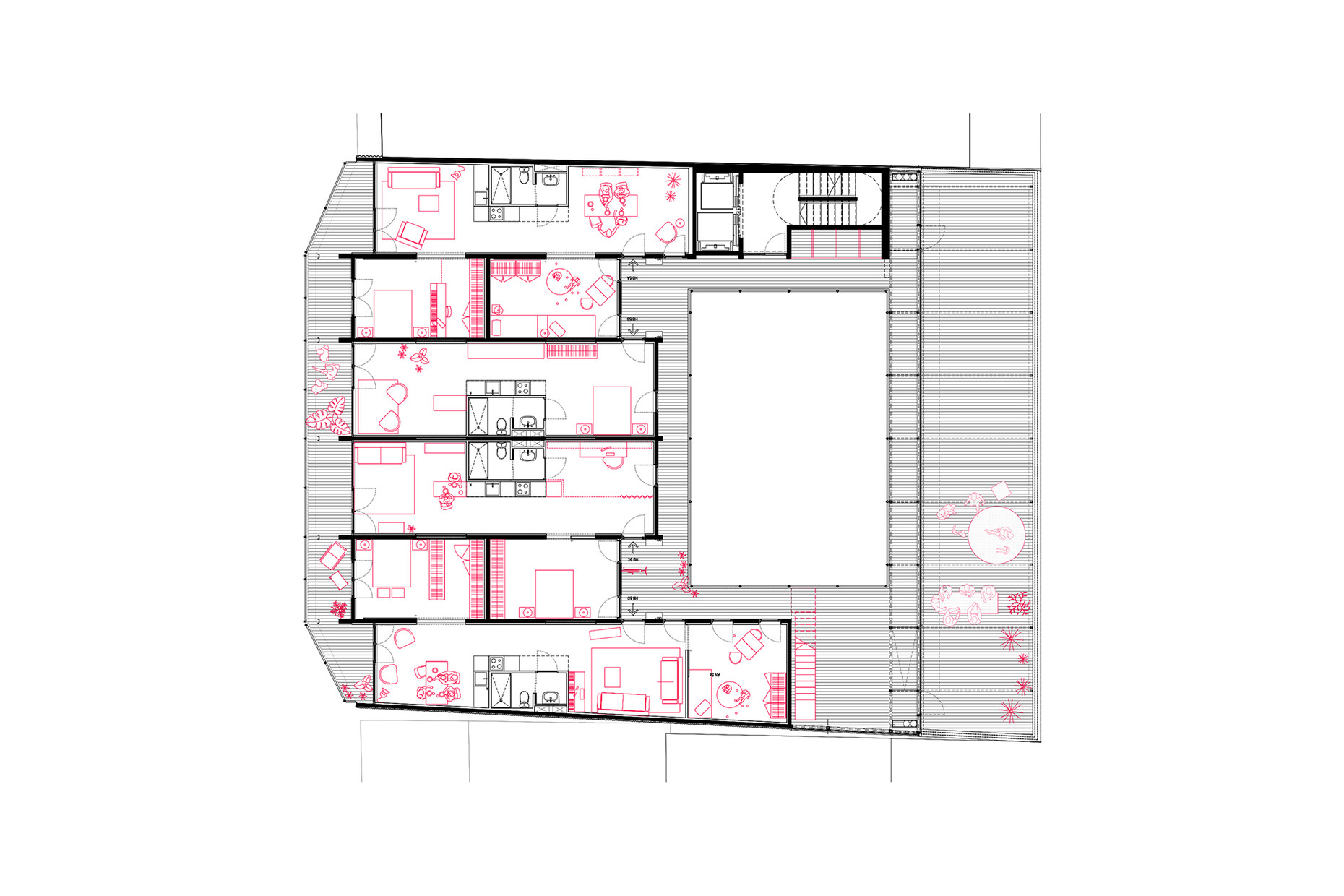

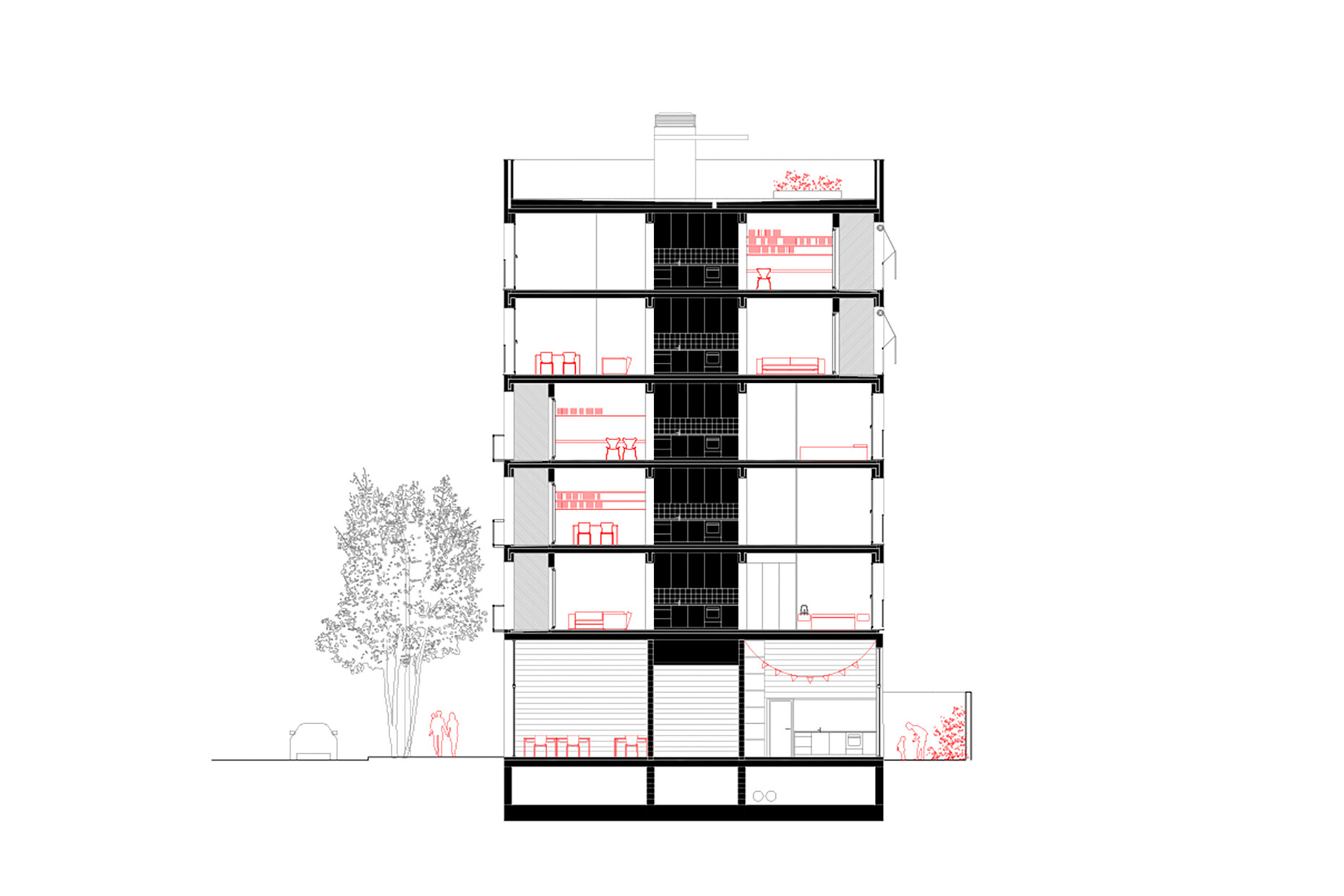

You just mentioned that community and creating spaces for social exchange is always at the root of your projects. What does this look like at La Borda?

Carles Baiges Camprubí: There's a large covered communal courtyard In the middle of the building that also serves as an access point. This means that the neighbours automatically run into each other there, which in turn leads to social exchange. I also live in La Borda, by the way, and to be honest, at the beginning I was worried that it might get quite noisy – but in the end the whole thing actually works very well.

Is there a lot of social diversity at La Borda?

Carles Baiges Camprubí: Our goal was to offer flats for different age groups. There are a total of 28 residential units and only one unit has a traditional family with two parents and two children. The remaining units have all kinds of constellations – from single flats with pensioners to large shared flats with students. La Borda is very diverse from an economic perspective as well. The neighbourhood has a large share of foreign residents, about 20 percent, which is unfortunately not reflected in the project. This has to do with its specific history and the processes associated with it. In our follow-up projects, we've therefore paid more attention to achieving diversity in this regard as well, which is why the proportion of those with foreign backgrounds is correspondingly higher.

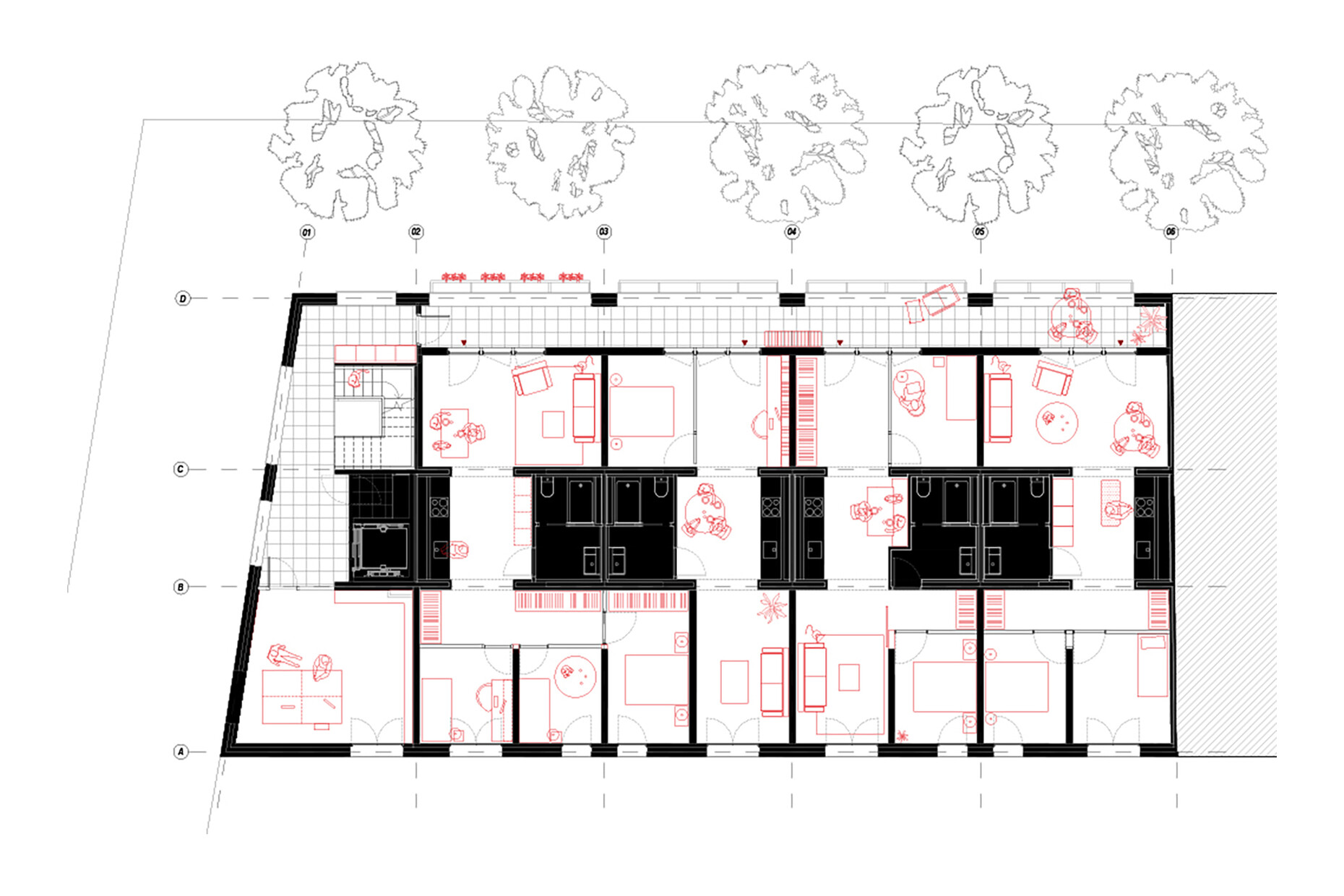

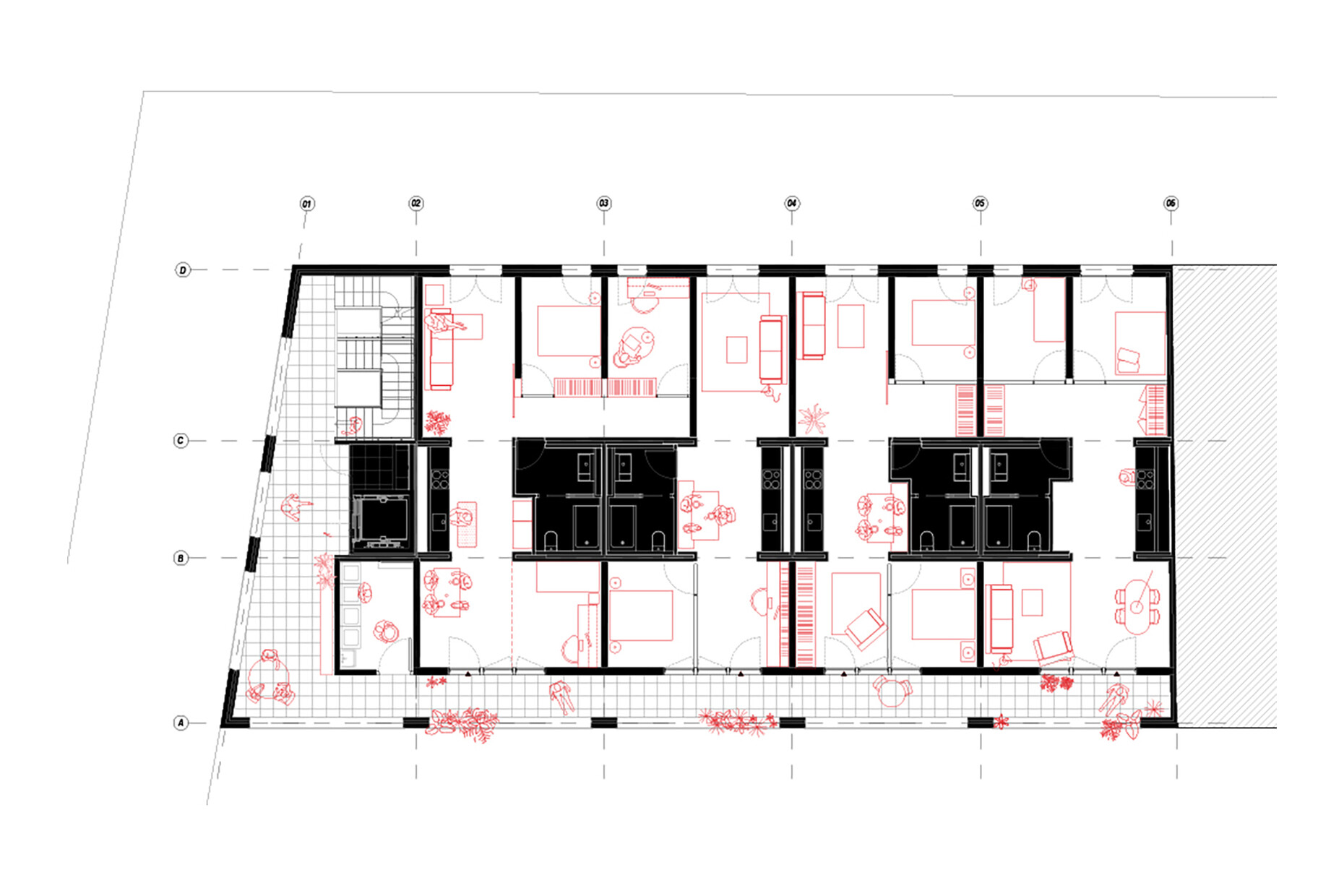

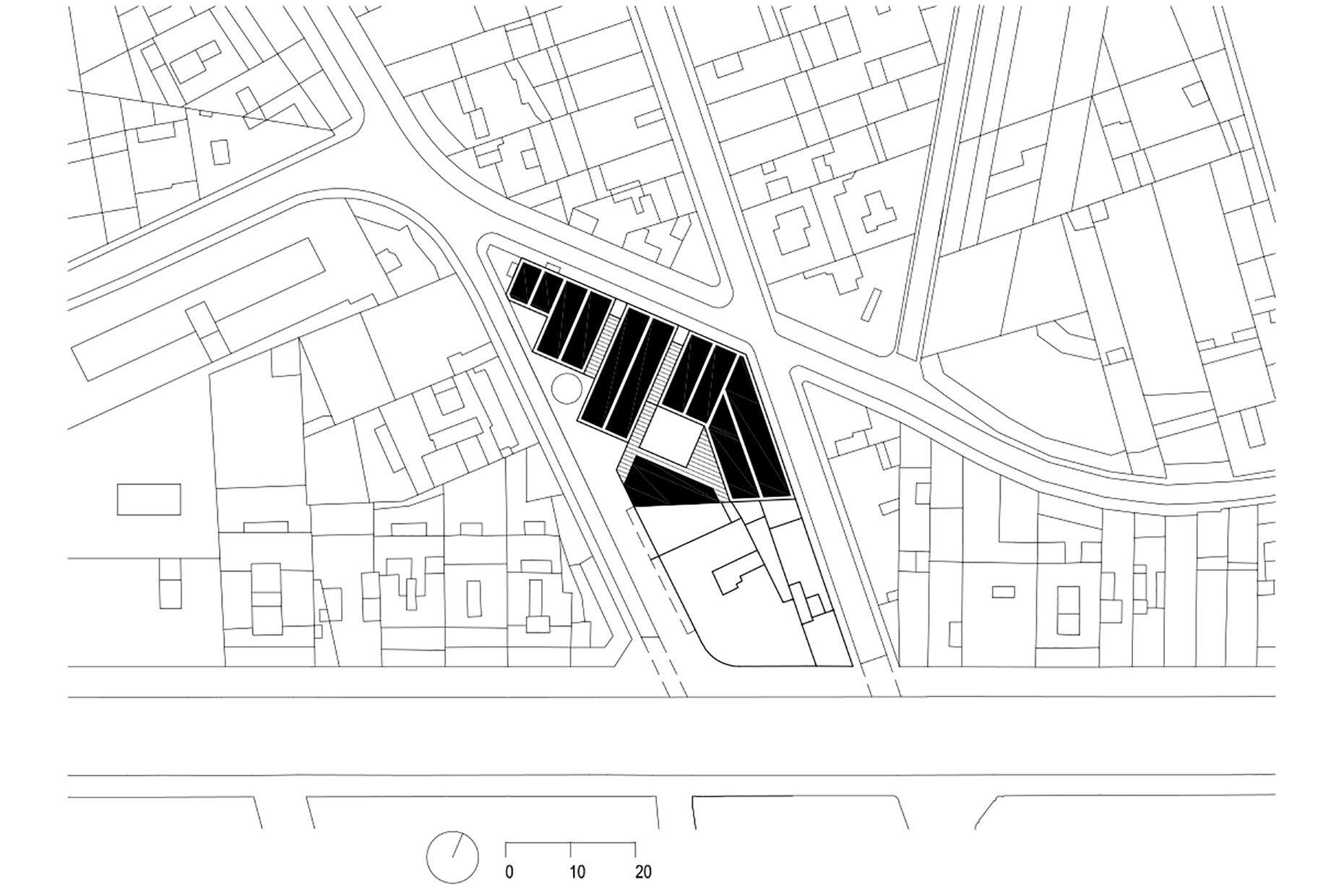

Another of your residential projects is La Balma, which is much smaller than La Borda. How did you create communal areas here?

Carles Baiges Camprubí: La Balma is an elongated building whose shape was derived from the plot of land it sits on. However, the goals and strategies we used for it were exactly the same as for La Borda. Therefore, there is also a connection between the communal areas and the access and circulation here – even though these areas are much smaller. They function like a kind of filter between the flats and the street.

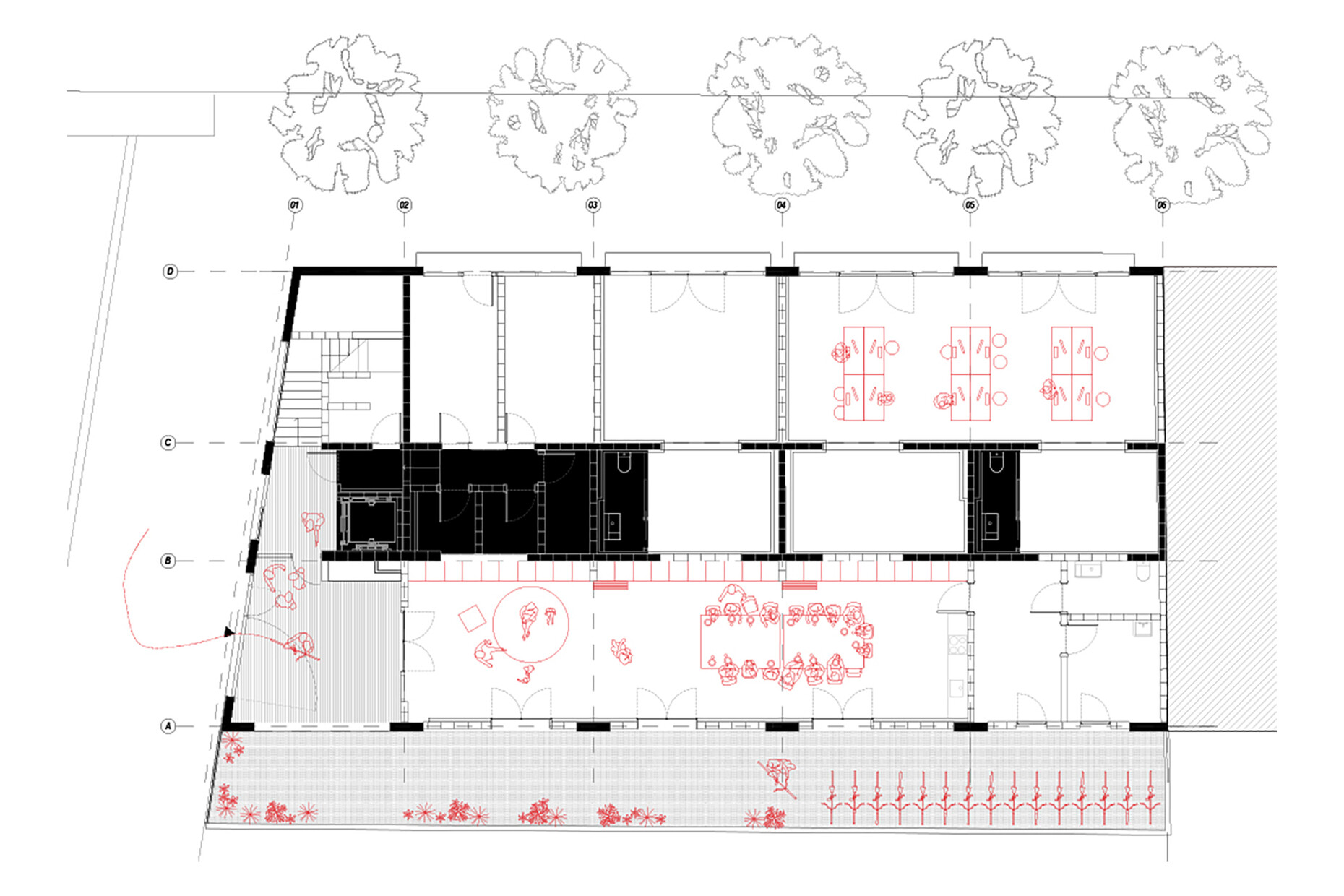

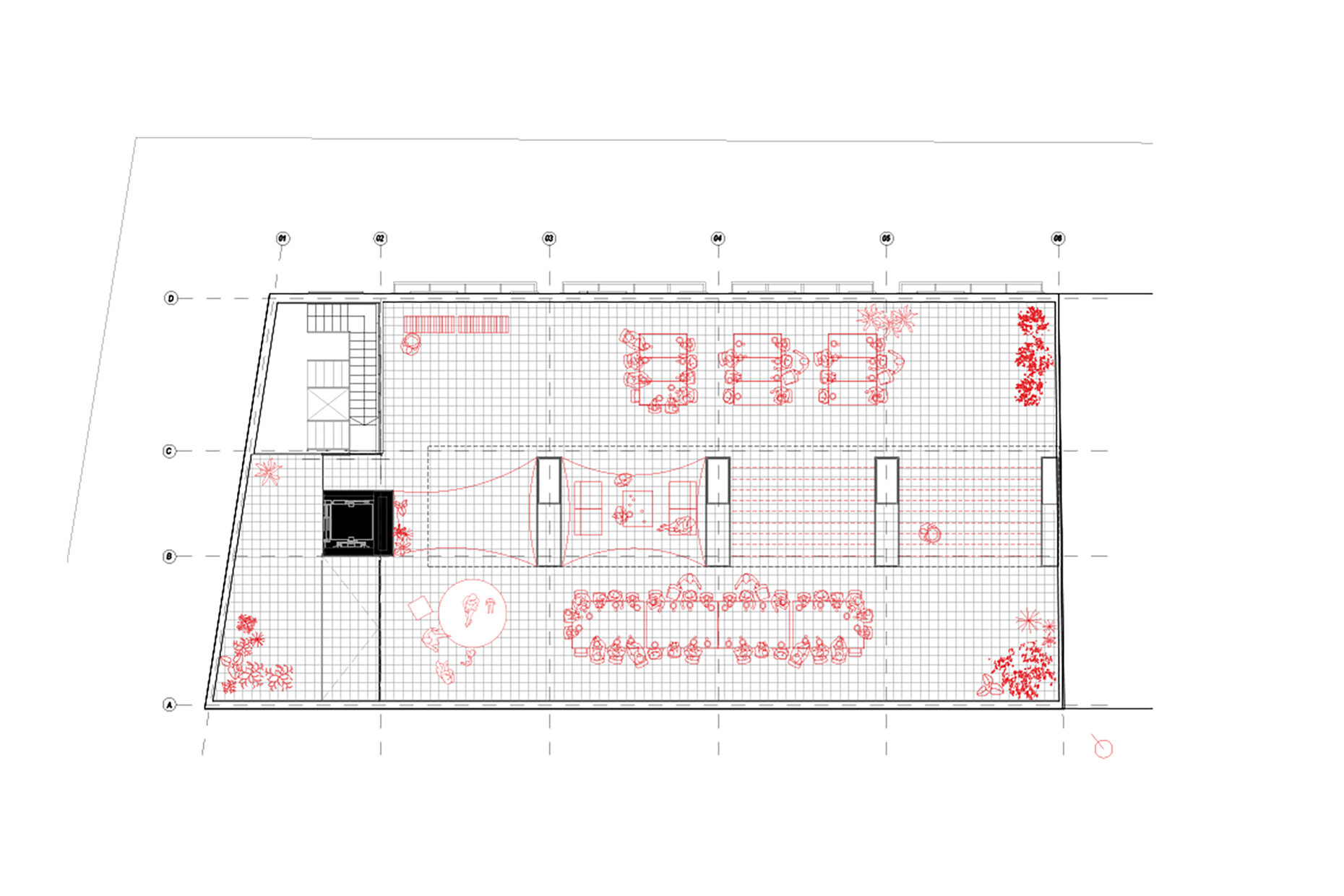

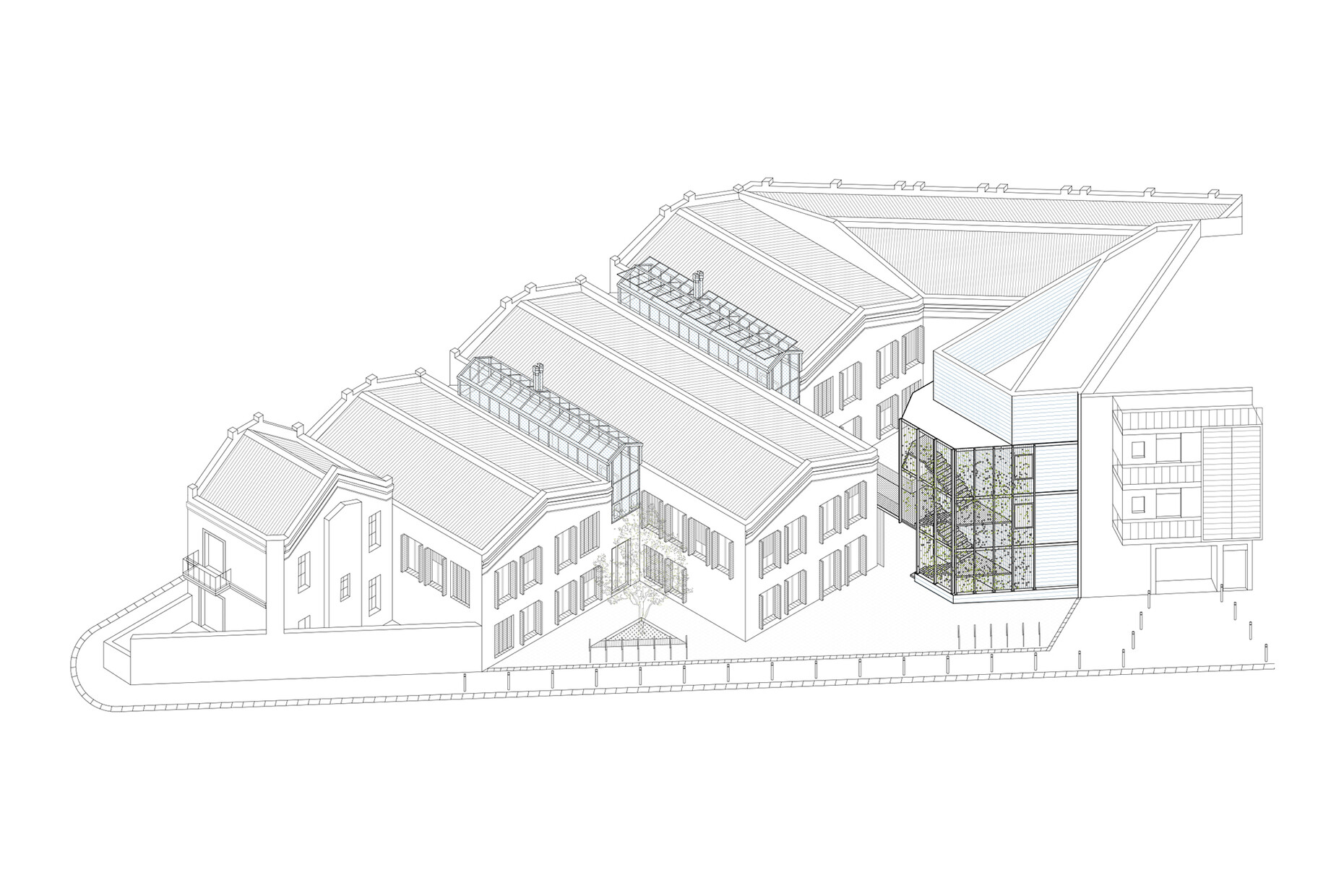

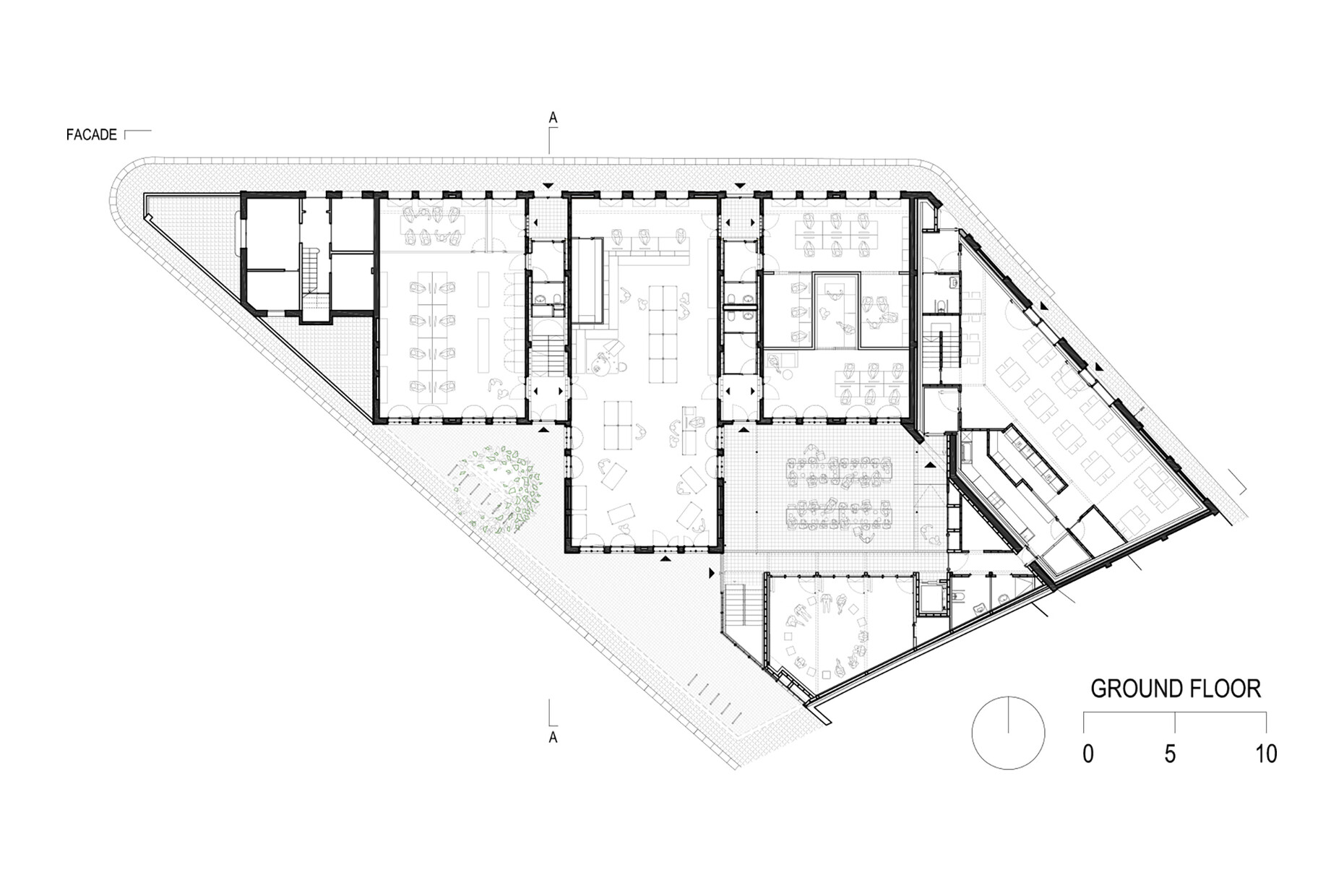

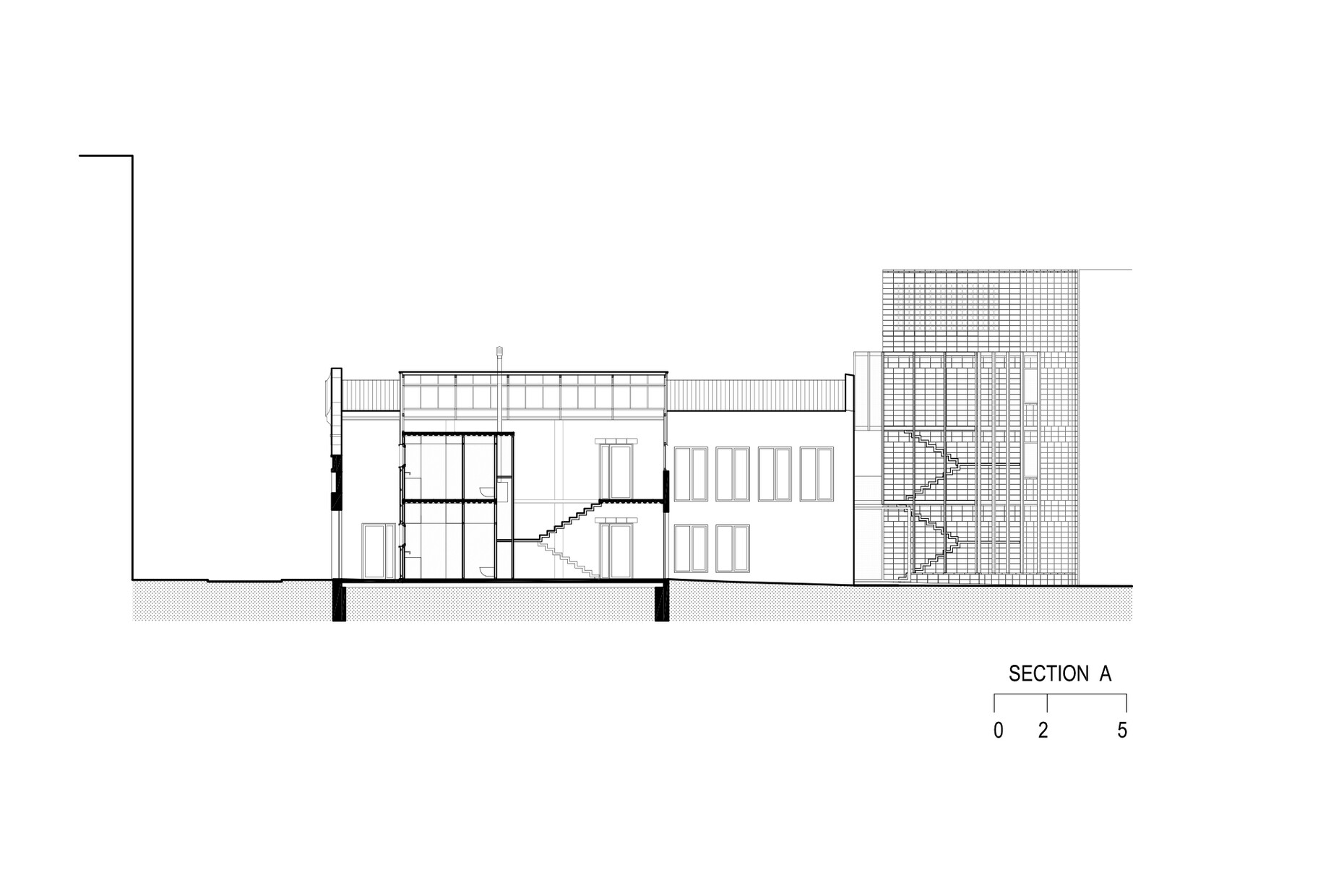

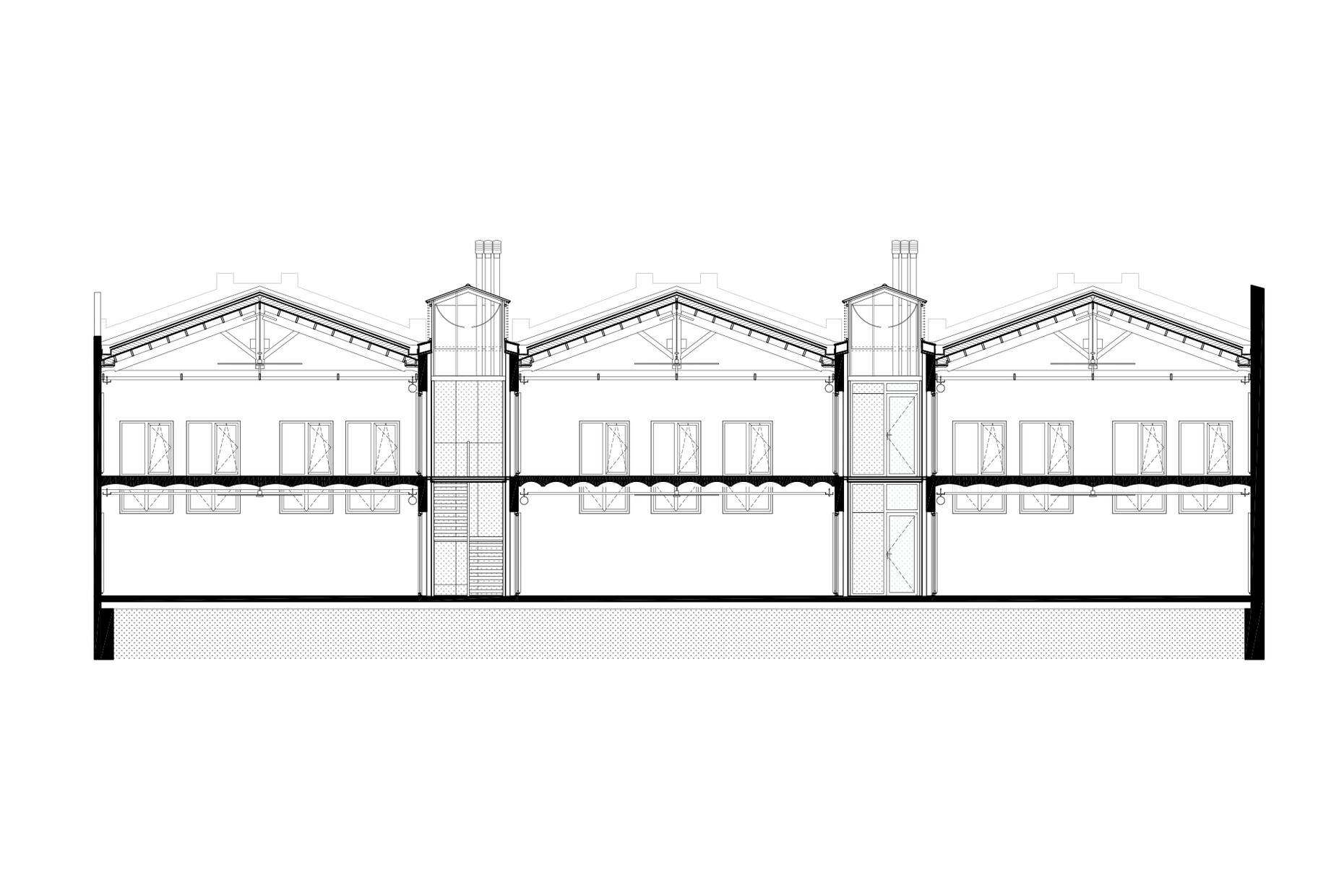

In addition to various residential projects, Lacol has also designed workspaces. One example is the La Comunal project. What's the concept behind this?

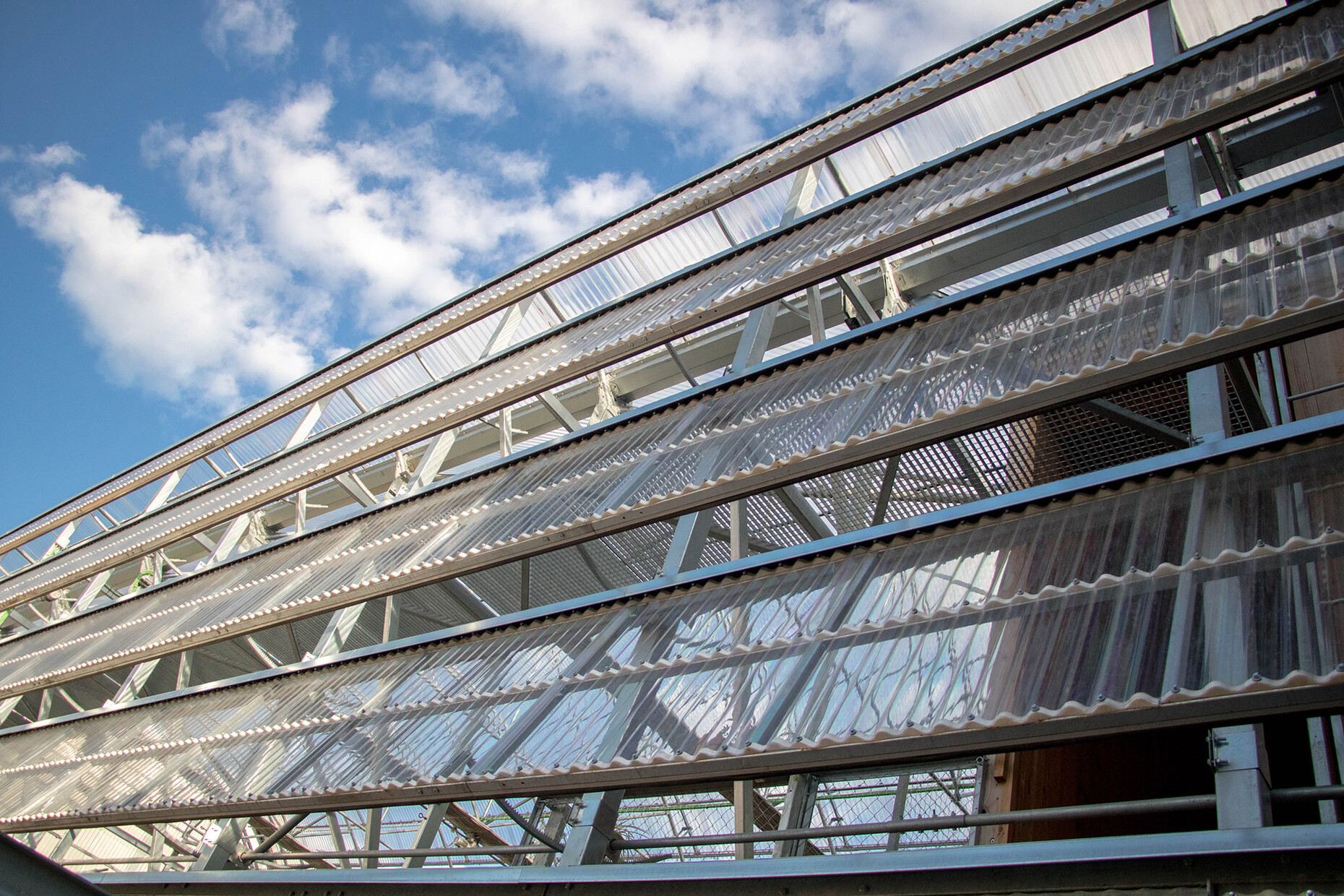

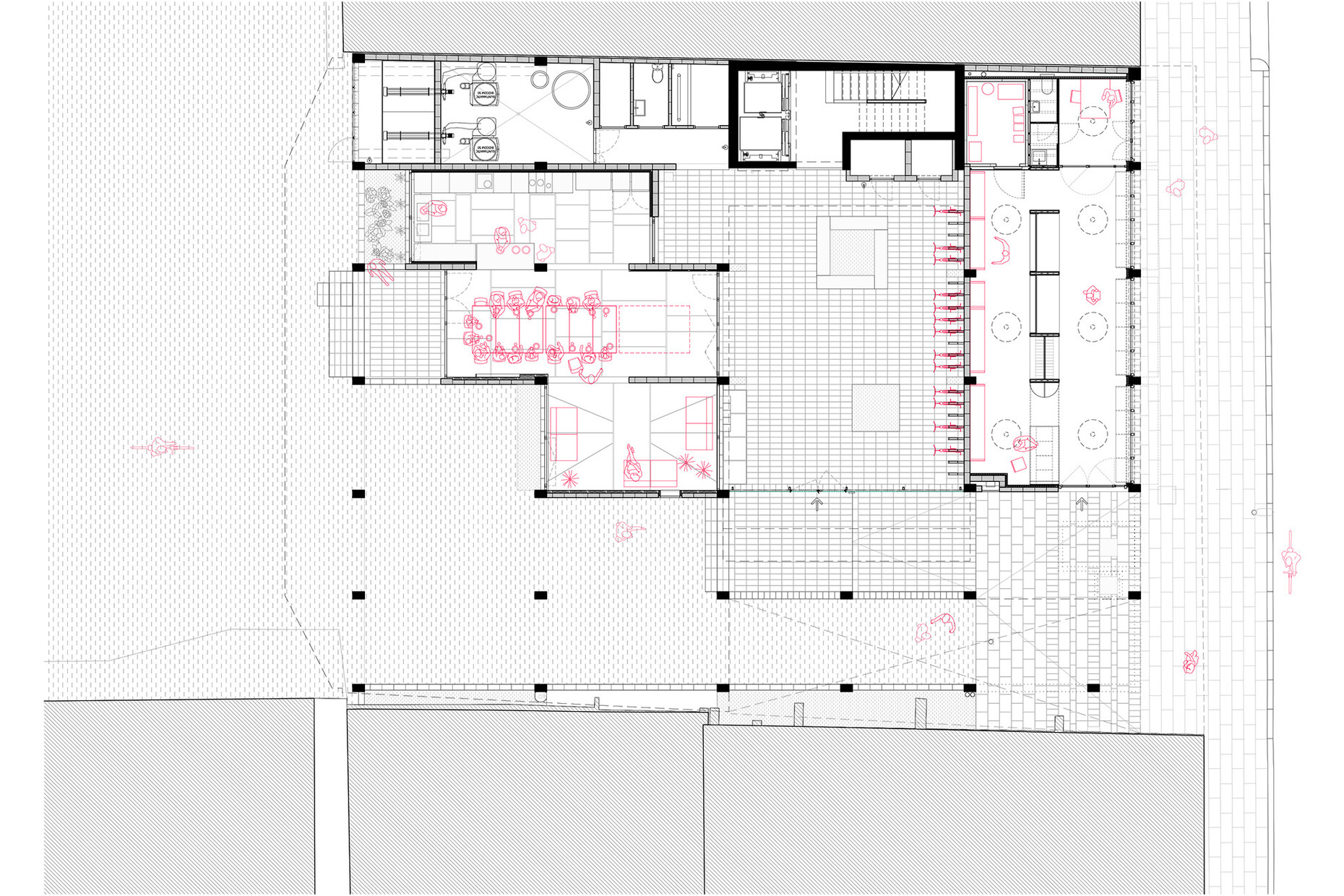

Carles Baiges Camprubí: La Comunal has a variety of work spaces that are shared by different organizations. We're also based there, and the project actually started when we joined forces with two other cooperatives from the neighbourhood to look for larger premises. The building that La Comunal is in used to be a factory, but it had stood empty for decades. We renovated it and it's now home to eight cooperatives, including a library and a language school. And La Comunal is also used as a venue for concerts.

Is the sense of community here also reflected in the architecture?

Carles Baiges Camprubí: Each organisation has its own individual space, but there are also areas that we share, such as the meetingrooms. There's also an inner courtyard that allows for social interaction. So, there are approaches here that can also be found in our housing projects. This process was also interesting because the building is listed, but we still wanted to implement our sustainability agenda. This wasn't always easy because of the heritage protection guidelines we were obliged to follow – but in the end we still managed to reduce the building's use of energy while respecting its original fabric.

What other projects are you currently working on?

Carles Baiges Camprubí: At the moment six more cooperative housing projects are being planned. Five of them are in Barcelona and one is outside the city. We're also increasingly involved with refurbishment projects, e.g., the renovation of old housing complexes, where issues such as community and sustainable building still need to be addressed.