Green Worlds

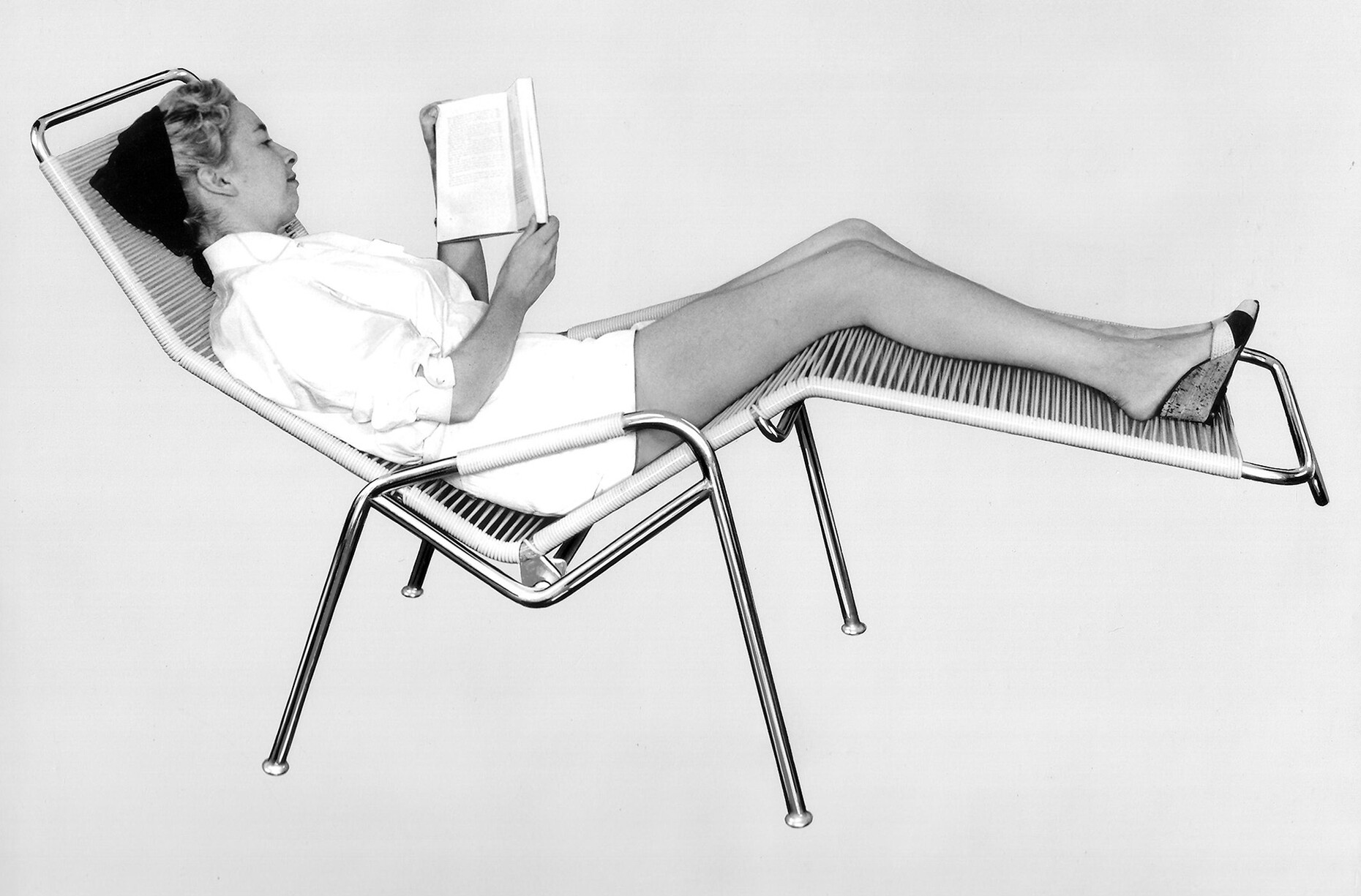

This exhibition is showing everything from that little medieval paradise which functioned as an “hortus conclusus” or enclosed garden, to Islamic courtyard gardens and Baroque palace gardens, even going as far as to include urban gardening projects. Since time immemorial, gardens have represented places of repose and relaxation, places for people to enjoy and engage in their own personal recreational activities. Gardens can also fulfill a productive function. At the same time, they reflect identities, dreams and visions – can indeed act as utopias, pointing out a better way to live. Comprising four chapters and stretching over four halls, the above-mentioned exhibition shows us how gardens can teach us to rethink and revise our relationship with nature. In the first room, a multimedia installation surveys the entire scope of historical gardens. For starters, however, visitors are greeted by a string of designer items on the subject, set out in a row along the walls – on the left, anything that might be useful for working in the garden, from rakes and spades to watering cans and dibbles, on the right, everything we might find for indulging in rest and recuperation in the garden – from a historical 19th-century iron garden chair to the iconic recliner dating from 1949 designed by Huldreich Altorfer, and Patricia Urquiola’s 2008 Tropicalia, a brightly-colored, cord-woven chair with armrests. No surprises so far then, for an exhibition at a design museum.

Politics of the Garden

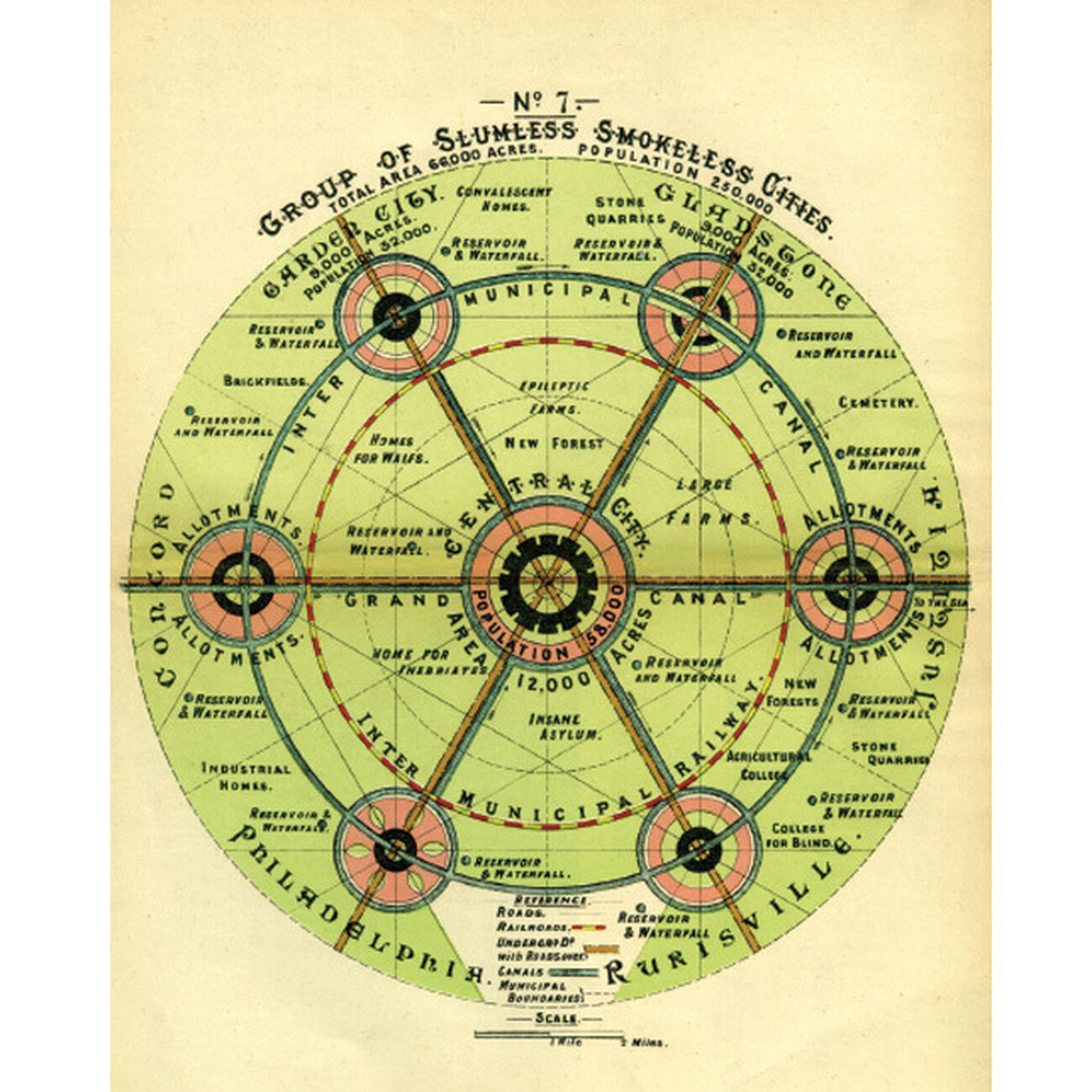

The second room is devoted to the political aspect of the garden. Quite a number of gorgeous flowerbeds have their origins in colonial history. Jasmine, fuchsias and chrysanthemums were originally discovered in distant countries and found their way to Europe in something known as “Wardian cases”. A prototype of this kind of case made of wood and glass was developed in the mid-19th century by an amateur researcher by the name of Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward; it is on display at the exhibition. It was an invention that was not only instrumental in colonial exploitation but also played a part in a whole string of complex ecological changes. The next-door hall documents the idea of the kind of garden city where even the less affluent social strata can become self-sufficient, using examples such as Hellerau near Dresden and including the relevant plans. Another subject that the show touches on is the theme of the green guerrilla movement. US artist Liz Christy came up with the idea for this movement in 1973. Her objective: To do something about the rundown and increasingly crumbling districts of New York City by dreaming up joint “green” projects. The urban garden as a place of social justice and participation – a notion that is still prevalent today. And if you are interested in sowing the “seeds of worker participation” in your own neighborhood, you will find instructionsn the display case on how to build your own reproduction of that seed bomb which dates from 1976 i.

“If you look at the history of gardens you will find that every era and every epoque spawns its own epitome of a garden,” comments curator Viviane Stappmanns. A number of these can be found in the third section of the exhibition, which focuses on nine seminal garden designers. It goes without saying that these include classics such as the work of landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx (1909-1994) who not only modernized Brazilian garden design but, with his research into his country’s indigenous plant life, also made a considerable contribution to the protection of the rainforests. Burle Marx composed his gardens like a painter, always in harmony with the buildings of contemporary architects. Examples include the rooftop garden for the Ministry of Education and Health in Rio de Janeiro, a building by Oscar Niemeyer in collaboration with Le Corbusier, Lúcio Costa and Eduardo Reidy. Faced with impending death, artist and film-maker Derek Jarman (1942-1994) in turn, created, in his home near Dungeness, Kent, a flourishing garden that was a real work of art. He had chosen his location in a place which most people would have considered impossible – on the barren shingles of the coast in the South of England and facing a nuclear power station. The garden by Jamaica Kincaid is more recent than this. It is here that the aforementioned author and gardener gets to grips with colonial history. In Kuala Lumpur, one of the world’s most densely populated megacities, the Kebun-Kebun Bangsar activists had to fight for their site for a giant communal garden. Piet Oudolf’s elaborate plants compositions also just have to be successful. The Dutchman, one of the most renowned contemporary garden architects, plans his gardens for all seasons. One example of these can be admired only meters from the show. In 2020, he designed the Oudolf garden for Vitra, immediately next to the museum’s parking lot, a garden which is currently just beginning to come into flower. It was his campus garden that served as the inspiration for devoting a major museum exhibition to the renaissance of the garden, as Mateo Kries, Director of Vitra Design Museum, explains to us.

A Garden of Ideas

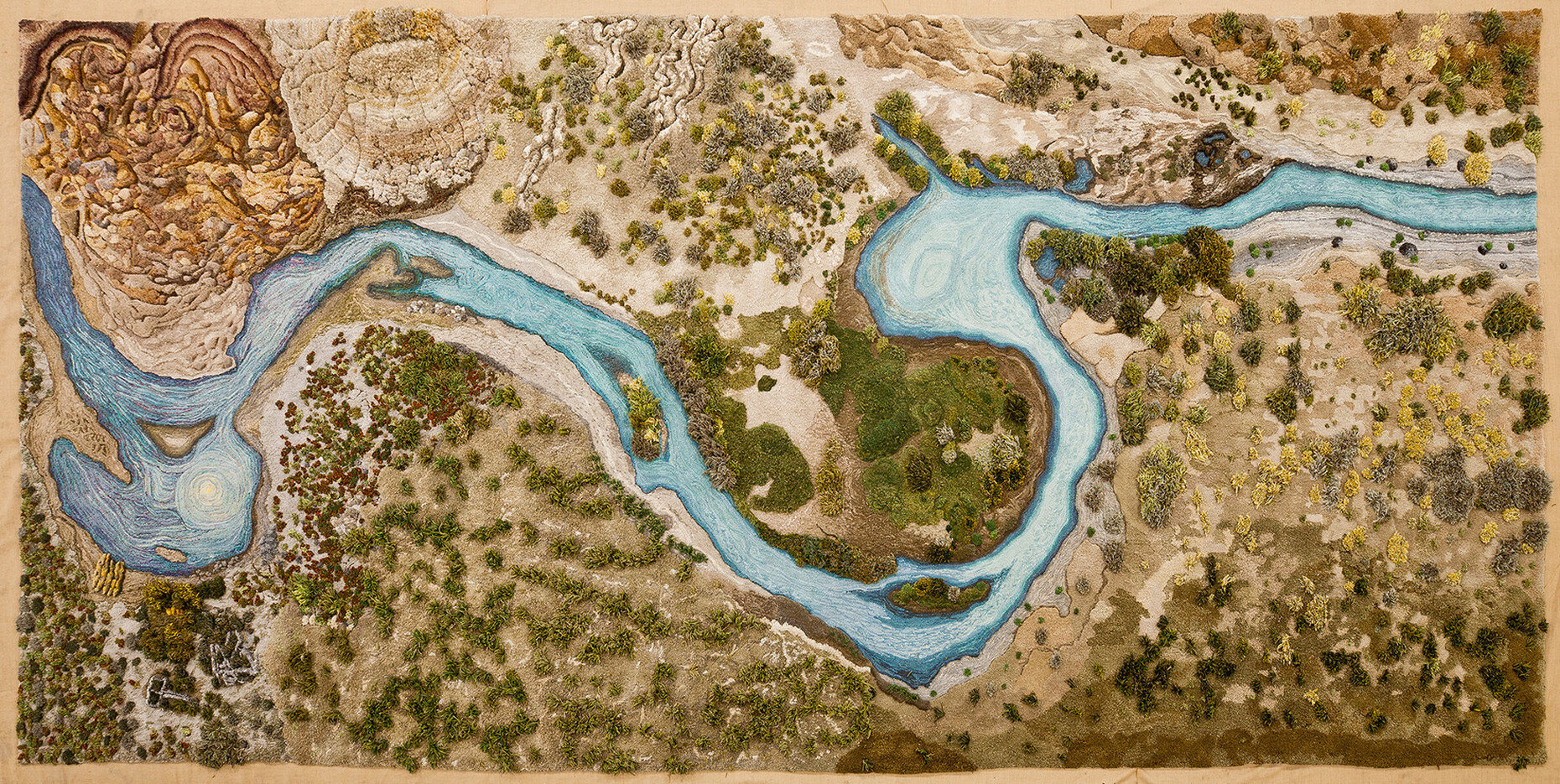

In the last part of the show the focus is on two pieces, an incredibly beautiful textile meadow by Alexandra Kehayoglou that is just crying out to be touched, and the largest item of all – an exhibit that is six meters in length by architect Thomas Rustemeyer. This focuses not only on traditional and indigenous projects, but also contemporary garden projects. Trendsetting developments are also sketched out here, ideas such as the efforts made by Basel-based artist Céline Baumann to defend the rights of plants, the concepts for urban microclimates advocated by Belgian landscape architect Bas Smets, and the combination of digital culture with gardeners in the Liao Garden by artist Zheng Guogu. A little bit more could be expected of these predictions about the future, something that the show’s title promises. The potentially sensual quality of this kind of topic also tends to fall by the wayside. And the symphony in different shades of green, a scenography orchestrated by Formafantasma, a team of Italian designers, is unfortunately rather predictable and not exactly experimental. Nonetheless, “Garden Futures” is a thought-provoking show and well worth a visit. It presents the garden not only as a romantic idyll but also as a place for trying out new things – for looking at social justice, climate change and biodiversity. “Paradise haunts gardens,” Derek Jarman once wrote, “and it haunts mine.”

Garden Futures: Designing with Nature

Until 3 October 2023

Charles-Eames-Str. 2

79576 Weil am Rhein

Daily 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.