SUSTAINABILITY

On Rotterdam’s Rooftops

It is not only since the onset of Covid that not enough greenery and too little space have been driving people out of the cities. Both reasons have something to do with the lack of space in our inner cities – but space is something that we need in order to create new parks. If we nonetheless want to bring green spaces into our cities, we need to be creative – as has been the case with New York’s High Line, where a defunct freight train line has been converted into a 2.33-kilometer park. The city of Rotterdam is currently doing something similar, only in the latter instance we are talking about 18.50 square kilometers and about nothing less than taking possession of the third dimension. That’s how large, taken together, the largely empty flat roofs in the Dutch metropolis turn out to be. And a number of options would be feasible on them, which is why the city has commissioned MVRDV, a Rotterdam-based architecture practice and "Rotterdam Rooftop Days" (Rotterdamse Dakendagen), a festival organizer, to put together a "Rooftop Catalogue" listing possible rooftop scenarios.

Taking possession of Rotterdam’s rooftop landscape is by no means a new venture for either party – since as long ago as 2015 "Rotterdam Rooftop Days" has been allowing for various different rooftop landscapes to be tried out at the weekends during the summer months and has been incorporating these experiments into a cultural program including exhibitions, dinners and concerts. It was in 2016 that MVRDV started attracting attention with its temporary staircase installation that was 29 meter high and 57 meter in length, realized as part of the festival "Rotterdam Celebrates the City". On that occasion visitors had the opportunity of exploring the roof of a building known as the "Groot Handelsgebouw", an office block dating from the 1950s on a square in front of the main railway station. With a total of 300,000 visitors who made the effort to trundle up and down the relevant 180 steps, this "stairway to heaven" was a success, despite safety concerns, and doubtless contributed to convincing the city of the potential in its rooftop landscapes. However, this is not the only architectural intervention that has attempted to make use of a second urban plane in recent years. In 2015, a temporary, 400-meter pedestrian bridge was designed by Rotterdam-based architecture practice ZUS (Zones Urbaines Sensibles). The bright yellow "Luchtsingel", as the project is called, connects three urban districts and spans both a tram line and the six-lane, lowered-suspension arterial road that is "Schiekade”. In the process, it docks onto the roof of the "Schieblock" which is partly used for urban gardening, and leads, amongst other things, to the "Luchtpark Hofbogen", a park on the roof of "Hofplein”, a former station.

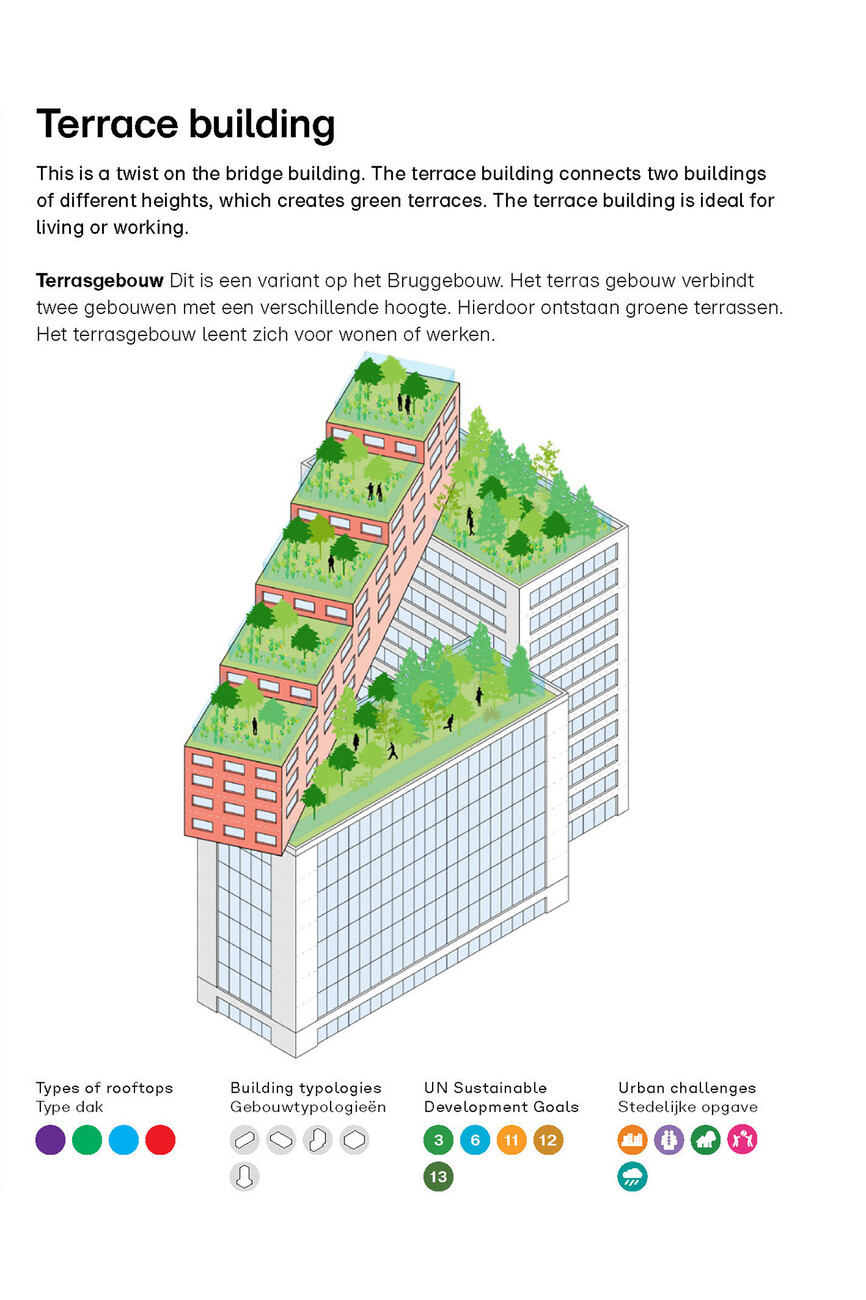

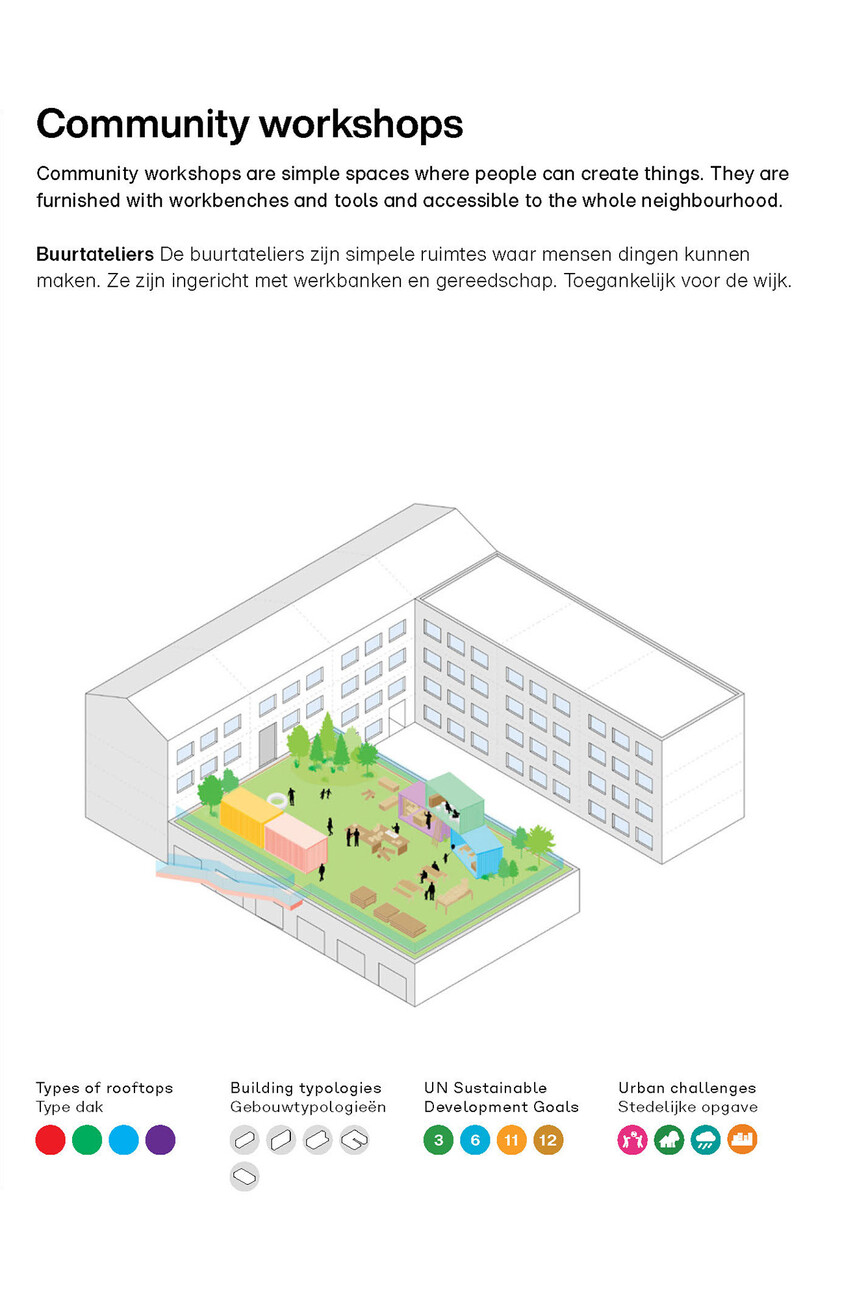

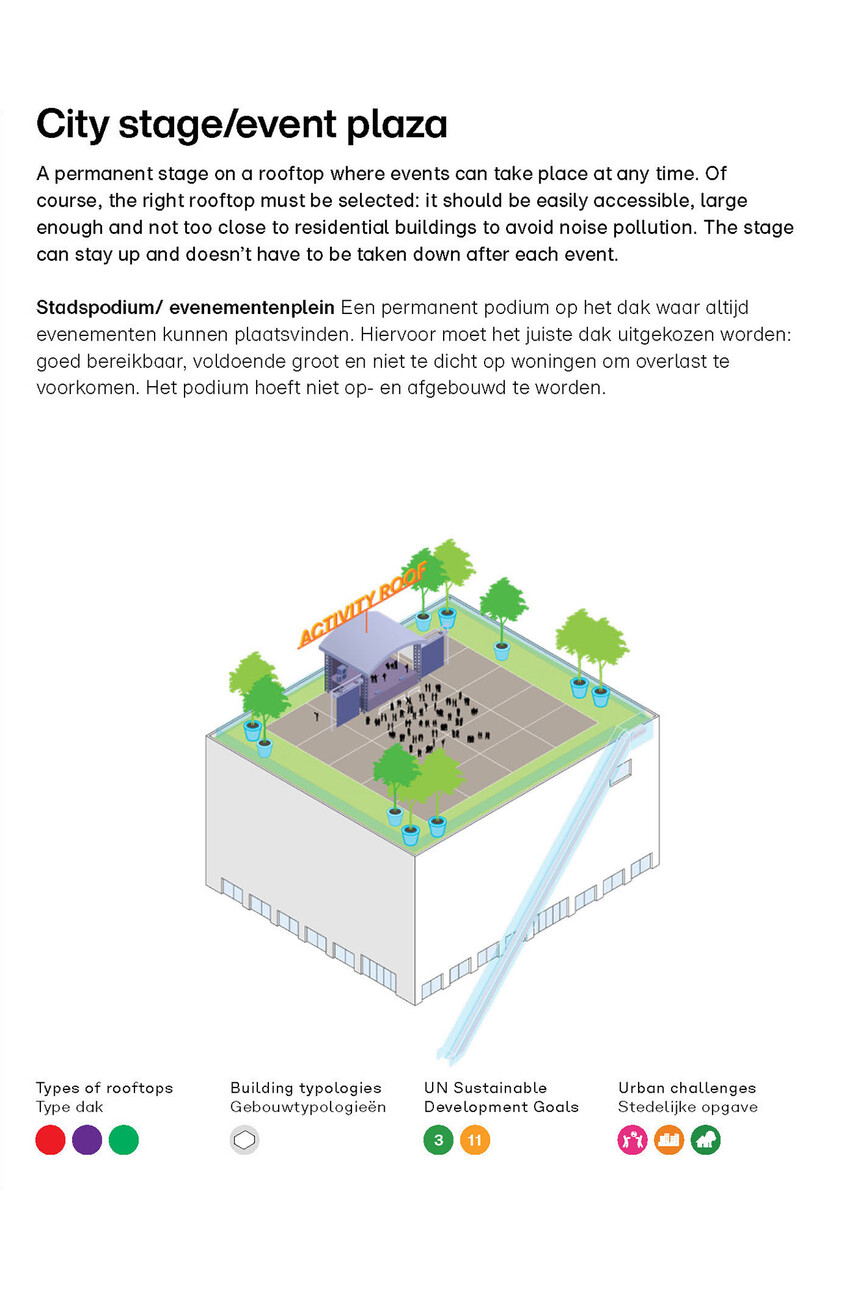

It is with this that the "Rooftop Catalogue" now ties up, using 130 suggestions to demonstrate everything that can be done with the expanses that are Rotterdam’s roofs. However, we are not only talking about extra green spaces but also about the greatest possible spectrum of possible interventions. "Rooftop use could make a huge contribution to boosting densities in the city – and it can also prevent us from building more on the outskirts of our cities. So that means not only adding a layer of greenery to rooftops, but also putting turrets on an elderly neighborhood or a skate park." In the "Rooftop Catalogue" colorful axonometric projections are used to illustrate this. Amongst other things, listed usages include sports facilities, communal areas, solar parks, the addition of greened stories to residential or office space, vertical gardens, and even a cemetery. The suggestions can be summarized under the headings of "Sustainability and greenery", "Densification", "Sports", "Recreation, Tourism, culture and leisure", "Neighborhoods and social cohesion", "Mobility, energy and (utility) services". However, listing the possibilities represents more of a source of inspiration than precise instructions for use, something that would, because the structure of our towns and cities and their accompanying conditions are so complex, hardly be possible any other way.

Despite the exemplary nature of the "Rooftop Catalogue" the municipal administration is expecting a pretty concrete impact on Rotterdam. Along with the above mentioned redensification, we are also talking about effects such as boosting biodiversity, easing the load on the municipal drain systems and lowering temperatures in the summer. "It is much warmer in the city center than along the edges of the city. If we can reduce heat exhaustion, it would be much more pleasant for everyone in the city. We could also prevent health problems in this way, especially for the elderly. On top of this, water storage is also extremely important: If water could be stored on rooftops and gradually fed down into the sewers, the streets would no longer be flooded every time there is heavy rainfall," comments Mattijs van Ruijven, Head of Urban Planning for the Municipality of Rotterdam. However, getting there is bound to be no easy task, starting with the kind of complicated ownership situations with which even regular urban expansions are faced. Furthermore, the framework construction-related circumstances need to be taken into consideration, circumstances such as the static resilience of the roofs and the use of the right kind of greening. This is something that MVRDV has recently demonstrated with an urban forest on the roof of a new art depot "Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen", where 75 specially cultivated birch trees have been planted at a height of 34 meters.

The discussion about taking possession of the rooftops is, not least, a discussion about the way our cities look. With this in mind, something that is bound to benefit the project is the fact that in Rotterdam there are fewer monument protection regulations in place than there are in such locations as Amsterdam. Winy Maas is nevertheless calling for new building legislation. "I think we need a new Building Code, or rather a Rooftop Code, with a helpdesk for the homeowners’ associations and corporations that take the initiative. You should be able to stack the four elements – water, greenery, energy, and population – on top of one another like a sandwich. It should be defined in some kind of regulation that rooftops should be able to support that weight. Stronger structures are more sustainable." Whether the city complies with this request and whether the approaches sketched out in the "Rooftop Catalogue" are actually feasible remains to be seen. Whatever the case, it has more than done justice to Rotterdam’s reputation as an experimental ground for architects and urban planners.