SUSTAINABILITY

Green is a colorful hue

Notwithstanding COVID-19, the climate crisis is still very much in evidence. Construction is often seen as a catalyst in this context, but can architecture help alleviate the climate crisis? This is the question explored in the exhibition “Greening the City” in Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt. For example, the exhibition examines how greened horizontal or vertical building shells can improve the city climate by reducing heat build-up in cities, lowering particulate matter emissions, and decreasing urban noise levels. The exhibition also highlights financial funding options and the political framework that can help contribute to a higher quality of live in built environments.

Alexander Russ: Ms. Strobl, what is the concept of the exhibition?

Hilde Strobl: I have to start by naming the target audience. The exhibition is aimed at citizens with an interest in the topic and provides answers on how buildings and places can be made greener. We not only look at existing buildings but also new ones. When preparing the exhibition, we designed a set of questions in order to find out what arguments in favor of or misgivings against the greening of buildings are out there. In addition, about six months ago we issued a call for projects. The underlying idea was that we wanted to present projects which demonstrate how easy the greening of a building can be – whether it is an urban farming project on a flat roof or a greened roof terrace. There are also so-called “best-practice” projects as architectural flagship projects.

What were the selection criteria for the “best-practice” projects?

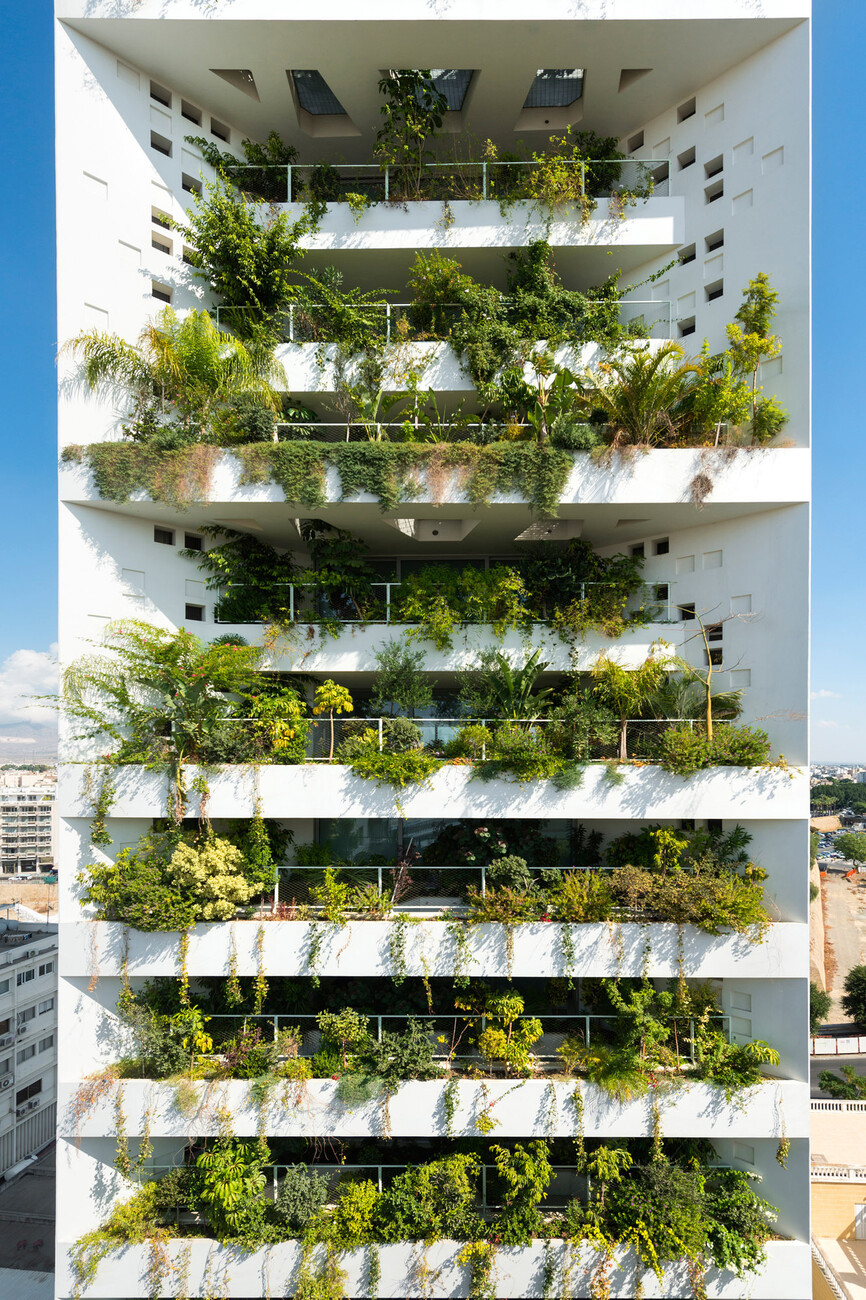

Hilde Strobl: We wanted to show that the greening of a building not only works in tropical climatic zones. Examples of work by Vo Trong Nghia Architects in Vietnam or WOHA in Singapore are repeatedly cited in this context, and are also included in our exhibition. But there are also examples of green buildings in Germany and Europe as a whole that demonstrate wonderfully just what is possible. Here we collaborated with Rudi Scheuermann from Arup, an expert for sustainable, energy-efficient building shells. The Kö-Bogen II in Düsseldorf by Ingenhoven Architects for example or a facade greening by Barkow Leibinger in Freiburg. The greening of buildings works all the better the more specifically the methods of greening and the respective plants are tailored to the respective climate and both the local and architectural conditions. The aim is to present various types of application. Some are very complex, others less so, and their environmental impact also varies.

And you not only showcase current projects but also older buildings like the so-called “Tree House” in Darmstadt dating from the era of Brutalism. What is so special about it?

Hilde Strobl: As long ago as the 1970s architect Ot Hoffmann experimented with plants on his own house and with the technical and construction material challenges involved. There were no tried-and-tested techniques for him to rely on. In fact, he used impermeable concrete without any additional sealing as an underlay for the beds on the large terraces and especially on the two roof terraces. Non-woven material was used to protect the roots. However, with his Tree House, and it was his own studio house, Hoffmann not only created a concrete structure but also a green oasis in the city. The house was also intended to act as the start of an urban renewal project that would literally connect Darmstadt’s city center with the Herrngarten by a bridge. Sadly, the idea did not progress beyond Hoffmann’s Tree House which still exists today as a listed building. At the time it was not only the concrete that drew criticism but above all the rampant growth of the plants on the roofs because Hoffmann pursued a concept that ran contrary to the Kö-Bogen II: He created the necessary conditions for plants such as soil, water and nutrients and installed the plants. And having done so, simply let nature follow its own course.

You mentioned a set of questions that you wanted to use to find out what arguments or feelings might exist for or against the greening of buildings. How do architects view the topic?

Hilde Strobl: There is a wide range of different opinions among architects on the subject. The arguments against it largely concern the greening of facades. This has to do with the fact that plants evolve while the architect and client want to know what the building will look like several years later. Moreover, some architects view the greening of a building as counterproductive to their own design because it disfigures their creation. However, that need not always be the case. For example, in the exhibition we show a childcare center in Frankfurt masterminded by Christoph Mäckler. The building that has since become completely covered in greenery has a clearly defined shape that is composed from several small saddle roof houses. However, the plants did not destroy it but rather lend it an additional level.

How is it possible to use greening to respond to the different aspects of a place such as daylight, ventilation or temperature?

Hilde Strobl: Naturally, such factors help to inform the design. But they also demonstrate how differently the greening of buildings is rated. A good example of this is “Bosco Verticale” by Stefano Boeri Architetti with its trees: Its opponents argue that the trees take up too much daylight, while those in favor say the trees provide natural shading which prevents the facade from overheating.

How would you assess “Bosco Verticale” against the background of your exhibition? Is the idea of a vertical forest something viable for the future or simply another example of spectacular architecture?

Hilde Strobl: I have to admit that initially I was critical but meanwhile I would say the project has proven successful. You have already mentioned the concept: a residential high-rise with a vertical forest in the facade. Naturally it involved an enormous amount of work and this was also one aspect that drew a lot of criticism. For example, it was necessary ahead of the project to work out how the trees could be supplied with sufficient water so they would not dry out and constitute a fire hazard. Since that time, there have been studies and assessments on the positive impact of the facade. Moreover, the project is a kind of prototype so this justifies the effort involved to some extent. Now Boeri builds vertical gardens worldwide, and that includes in Germany. This summer a social housing project in Eindhoven will be completed, the so-called “Trudo Vertical Forest” that works according to similar principles.

What can politics do regarding the greening of buildings?

Hilde Strobl: They can make demands and provide support. For example, the city of Frankfurt sponsors private roof and facade greening or unsealing to the tune of EUR 2 million a year while Stuttgart insists 30 percent of new urban buildings are greened. However, since with greening it is existing buildings that play a major role it is difficult to introduce regulations for all states. This is why building greening has not been anchored in building regulations. In other words, it is up to local authorities to regulate everything.

Do you also show projects that are the result of local initiatives or participatory models?

Hilde Strobl: We showcase these projects in the section devoted to projects submitted in response to our call, as I mentioned initially. One example, would be tenants’ communities, who have persuaded their landlords to green a roof terrace that everyone then uses. When different people get together these are often the most interesting projects, then it is automatically more colorful.