The future house of God

Copenhagen continues to grow, even more strongly than expected. Current forecasts predict that the Danish capital will welcome over 100,000 new residents over the next 30 years, bringing the total population to 780,000. This will put additional pressure on the already strained housing market. It helps that the city has been pursuing an exemplary and continuous development plan for several decades, focusing on climate-resilient urban redevelopment, the construction of new residential areas and the expansion of public transport and bicycle mobility.

Since the mid-1990s, the new Ørestad district has been under construction on the island of Amager in south-east Copenhagen. By 2030, around 20,000 people will live here, and around 60,000 jobs and training places will be created. Thanks to a forward-looking transport concept, it already takes only seven minutes to reach the city centre and six minutes to reach the airport, which is located in the south-east of Amager. Clearly, this is by no means a suburban location. In addition, Copenhagen has a long tradition of high standards when it comes to the design quality of both new buildings and public spaces. In the south-west of Amager, around 20 square kilometres have been declared a nature reserve, while at the same time several architectural icons have been created in Ørestad, including high-rise hotels by Norman Foster, the new Copenhagen Concert Hall by Jean Nouvel and the spectacular Aquarium "The Blue Planet" on the shores of the Øresund by 3xN – but pioneering projects also include a new recycling architecture like the multi-award-winning ‘Resource Rows’ apartment block by the architects of the Lendager Group with facades made from reused brick fields.

This will soon be joined by a significantly smaller and more inconspicuous new building, which, on closer inspection, is hardly less spectacular: the Ørestad Church, designed by Henning Larsen Architects. The firm won the competition in 2022, and the church is currently under construction and is scheduled to be officially opened in 2026. When completed, it will be the first new church building in Copenhagen in over 30 years. The church is being built on behalf of the Evangelical Lutheran Folkekirken in Denmark and its parish of Islands Brygge, which is responsible for Amager. Although the number of members of the national church is declining, more than 70 per cent of the Danish population still belong to this church, making it by far the largest religious community in the country. The aim was therefore to establish a welcoming new building in the new district. Intensive consideration was also given to what a church building should offer today. Among other things, surveys were conducted in the emerging neighbourhood.

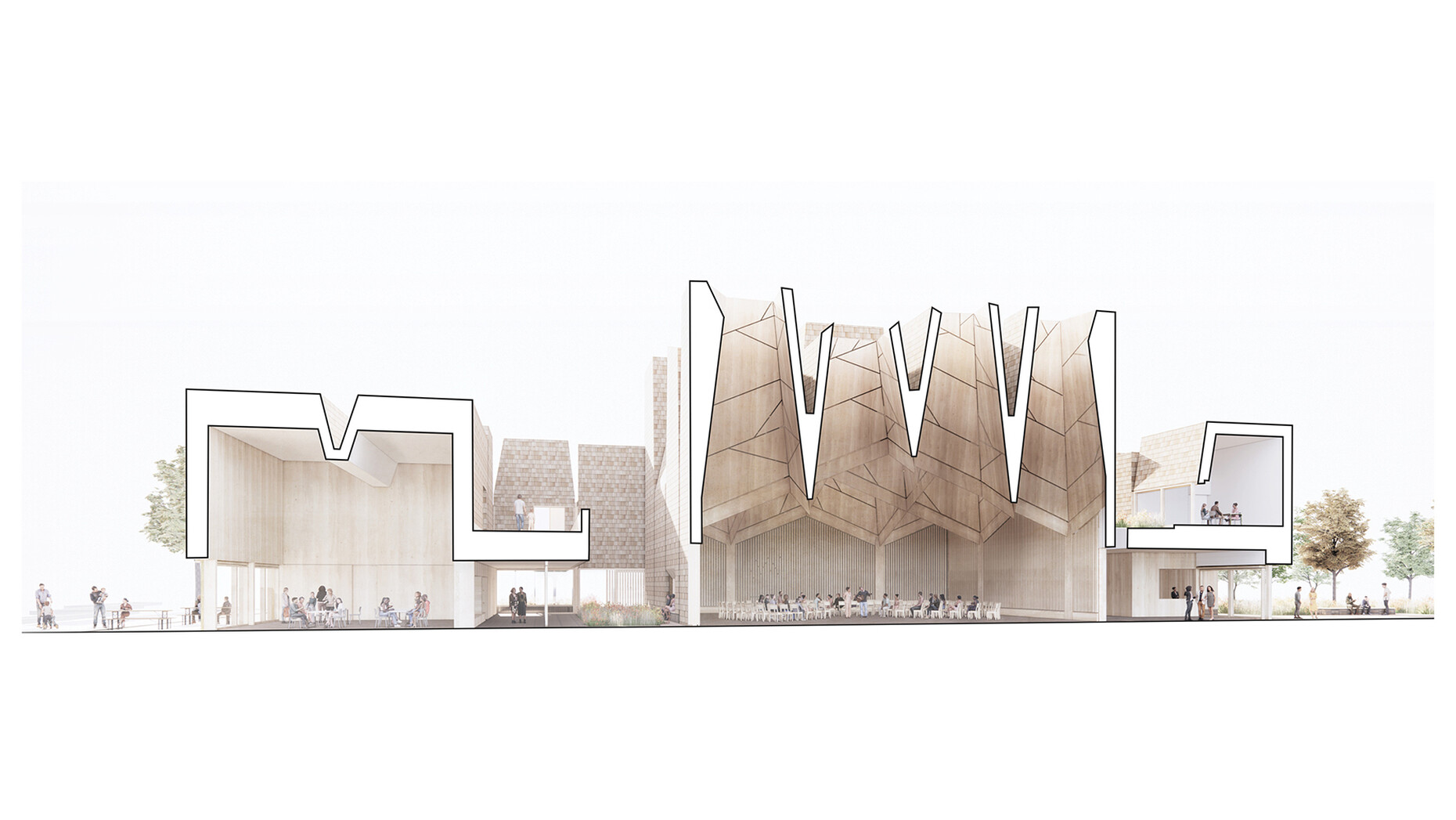

‘In new neighbourhoods like Ørestad, meaningful indoor gathering spaces are rare,’ says architect Greta Tiedje, Global Design Director at Henning Larsen and responsible for the project. This presents a great opportunity for the church. ‘Ørestad Church was designed to serve both spiritual and everyday community life, providing flexible, welcoming spaces for parish members and the wider public, including informal cultural and social activities.’ The building offers a variety of rooms of different sizes, a chapel, administrative offices, an enclosed courtyard with the atmosphere of a monastery garden and a large hall. It is actually a mixture of church and cultural centre: The flexible floor plan allows for different forms of worship and ceremonies, as well as cultural and social events, club meetings, educational programmes, meditation or yoga classes. It is about the integration of everyday activities, but also about moments of silence, contemplation, renewed attention and reflection. Tiedje speaks of ‘social sustainability’. The new church will cater to the entire neighbourhood, regardless of religious affiliation: a house of worship for all.

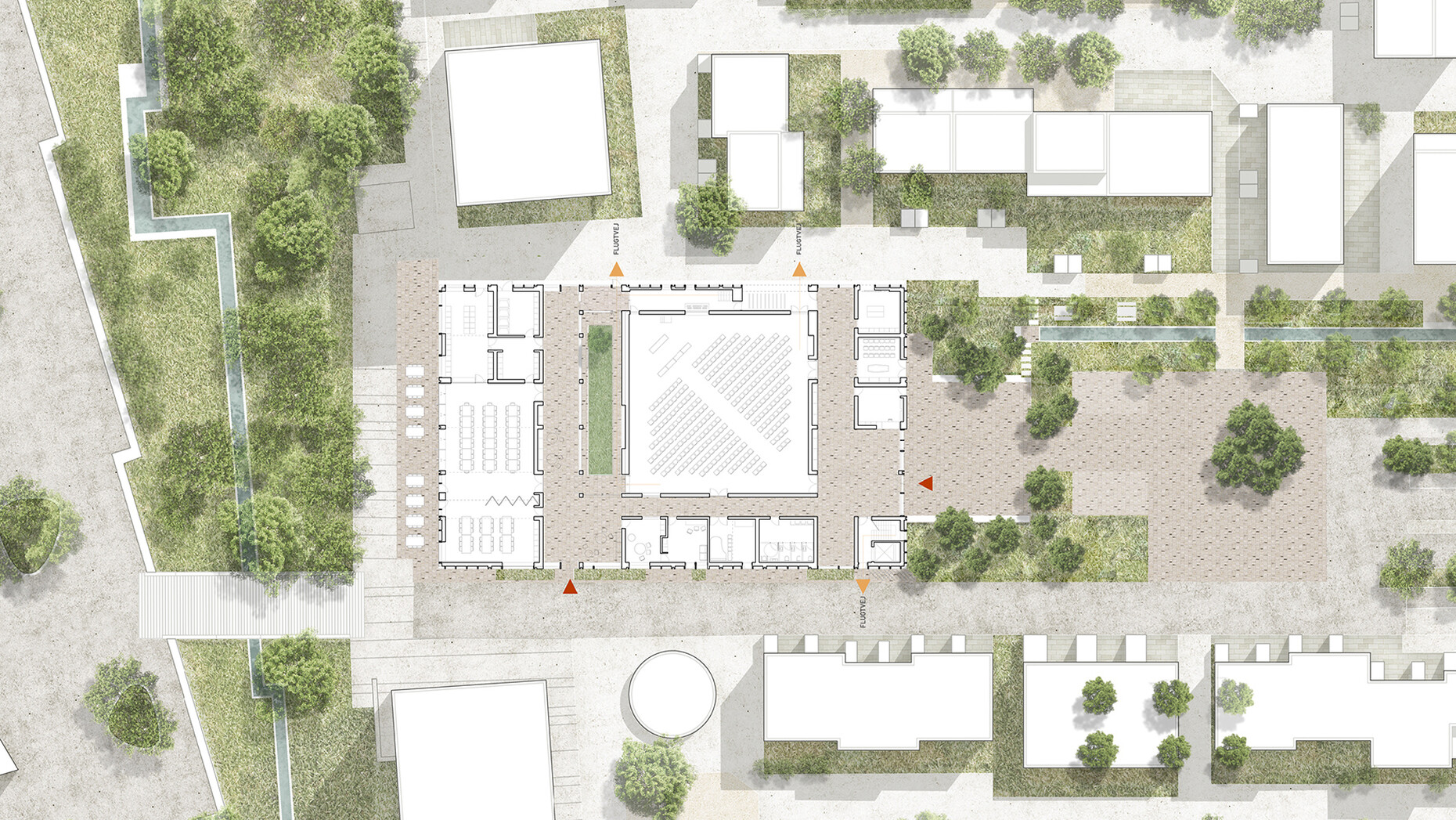

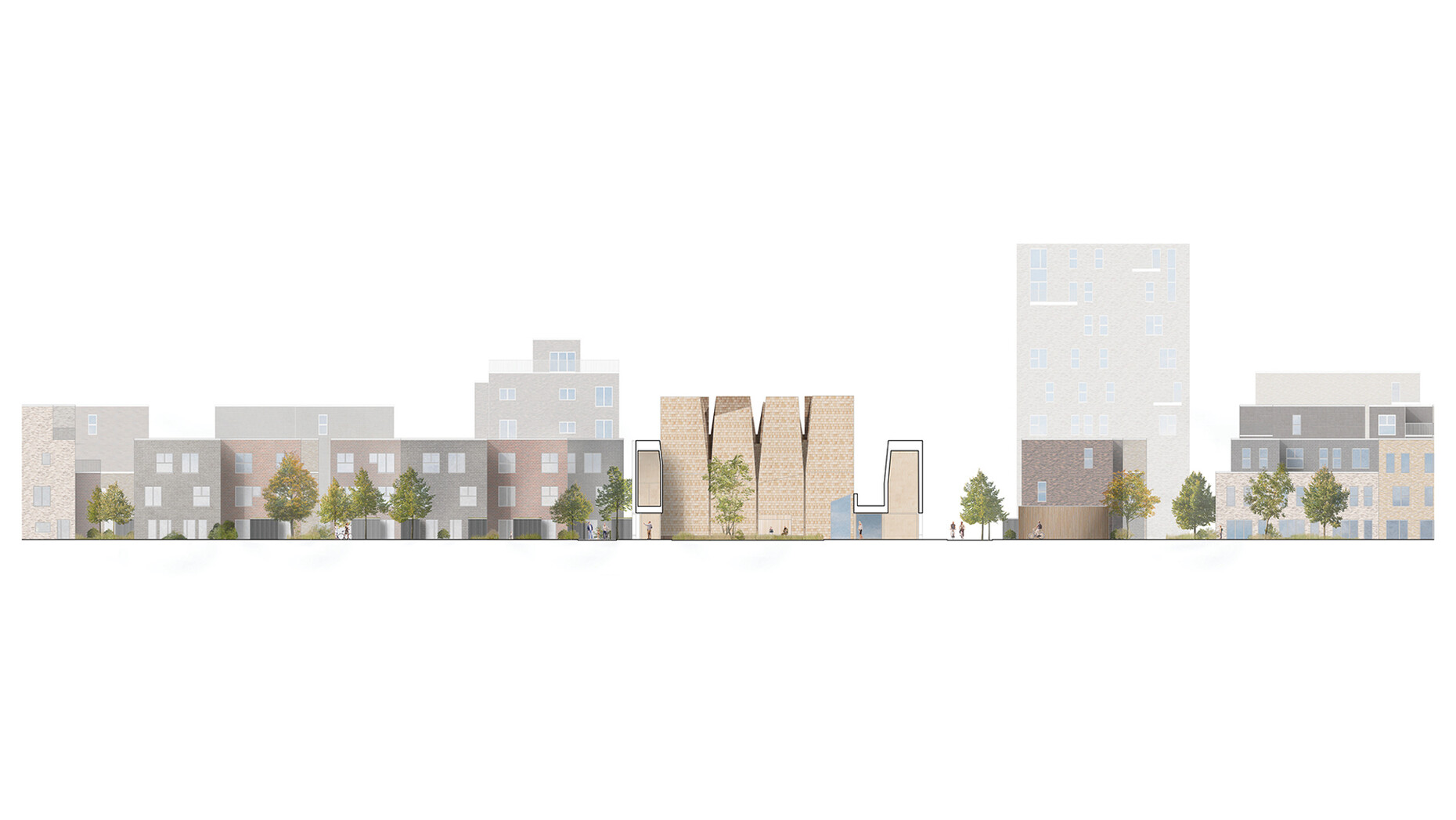

This is nothing new, adds Tiedje. ‘Over the past 20 years, Danish churches have increasingly combined spiritual and social purposes. Our project in Ørestad continues this approach, with adaptable furniture, open sightlines, and spaces that engage with the surrounding landscape, encouraging both parishioners and the wider community to gather.’ This would remove any inhibitions about venturing inside – both for the congregation and for the entire neighbourhood. The large display windows are only one part of the remarkable exterior of the church building, which eschews any hint of intimidating or awe-inspiring monumentality. This church is being built on a rectangular floor plan with an area of around 2,000 square metres at the northern end of a square. The traditional insignia of a church building are missing. There is no bell tower, the building does not stand on a pedestal, there are no stairs leading up to it and, at least in the architects' visualisations, there is not a single cross to be seen. ‘The layout is open and horizontal rather than enclosed and vertical, the interior is flexible, and it maintains a strong connection to the surrounding landscape.’ There are several relatively equivalent entrances and exits. The floor leads into the interior at ground level as an inconspicuous continuation of the street pavement, with only the colour of the stones used changing.

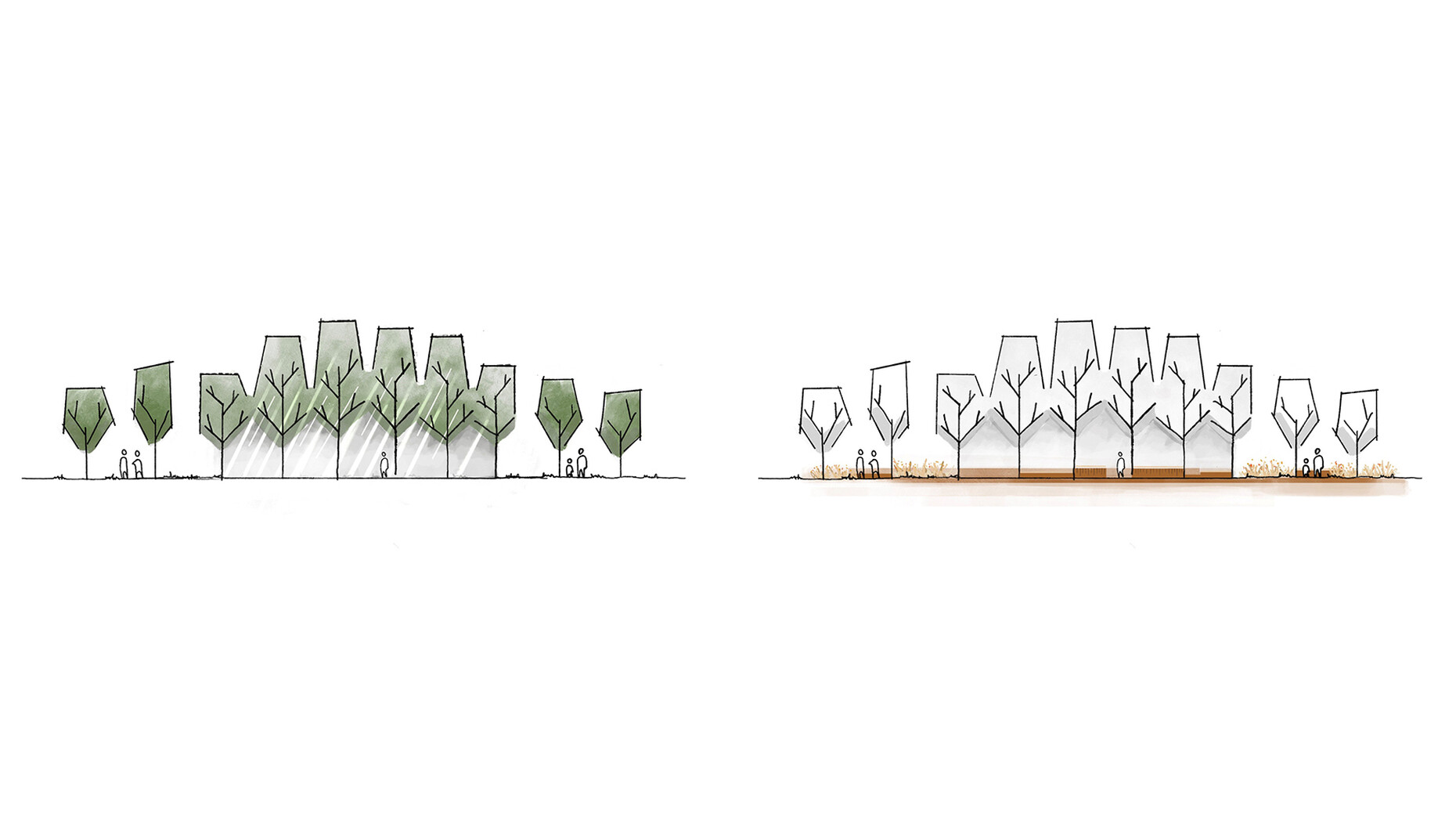

On the outside, the warm tones of the small wooden shingles dominate the appearance of the façades. They are made entirely from Canadian cedar tree remnants and take on a silver-grey tone over time. Where the façade does not consist of shop windows, it offers small seating niches, a cupboard for book exchanges, a small drinking fountain or even small tables for playing chess as an ‘urban shelf’. This is also intended to attract people and literally bring them closer to the building. The roof structure supports the desired expression. Instead of a single surface spanning the entire building, the house is visually broken up into individual cuboids by strong joints in the façades. These taper upwards in different directions, giving the structure a slightly organic feel without appearing overly playful. In a figurative sense, the individual bodies are meant to symbolise a community coming together – like people in a church or trees forming a forest. Towards the centre, this community becomes almost imperceptibly denser: above the large hall, 16 of these roof hoods sit like square honeycombs. At 13 metres, they are higher than the others and thus clearly mark the position of the hall, which is otherwise completely inside the building, from the outside.

Each of the honeycombs above the hall contains a skylight through which filtered daylight falls. The space is thus intended to resemble a clearing in the forest, where the light casts ever-changing patterns on the floor throughout the day – a place of sensual contemplation that also connects with the landscapes in the nearby nature reserve, according to the architects at Henning Larsen. The light ceiling above the hall is the only place in the building where the structure had to be reinforced with steel beams and steel columns. Otherwise, the entire new church building is constructed as a skeleton structure made of glued laminated timber. The walls are being constructed as timber frame structures, and the ribbed ceilings are made of laminated veneer lumber. This results in significant CO2 savings compared to a conventional reinforced concrete building. I ask Greta Tiedje whether I can also see the design as a continuation of the centuries-old tradition of wooden churches in Scandinavia. Of course, she says, but it is also a contemporary interpretation of that history. ‘Tradition inspired the use of timber, warmth, and attention to detail, but the design creates a new kind of space –simultaneously sacred, social, and inclusive.’ But the sculptural roof construction, the usable shelf façade and the integrated landscape elements in the inner courtyard also demonstrate the contemporary continuation of tradition.

All in all, the new church building in Ørestad is an example of the kind of architecture we can expect in the 21st century: in the coming years, the challenge will be to develop architecture and construction methods that meet the ecological and social demands of our time without losing the joy of good design. In contrast, the surrounding icons such as the aquarium and the concert hall, although barely fifteen years old, already seem like hopelessly outdated buildings from a bygone century. However, we will only be able to assess whether the church building can actually fulfill all its intentions after its inauguration later this year. We will sure go – after all, it is easy to get there, especially by bicycle or public transport.