HEALTH

Healing architecture

In its film on “The Hospital of the Future” OMA addresses the conventions of healthcare design. A team from the Dutch architecture office led by OMA-Partner Reinier de Graaf examines how hospitals are built and what role illnesses play in planning cities. The film offers speculative insights into the future of hospital architecture and seeks to trigger a debate on what shape an adaptive urban planning for health and care should take. It will be on view in the Architettura 2021 Biennale in Venice, in a setting featuring larger-than-life hospital curtains and field hospital beds acquired from the Italian army.

Alexander Russ: How did you become interested in the topic of healthcare?

Hans Larsson: At the beginning it was a practical interest because we started working on two hospital projects. We entered a bid for a medical masterplan in Qatar and a hospital in Paris. The whole thing meant exploration of a terrain with which we were not at all familiar.

What did you know about hospital design at that point?

Hans Larsson: Nothing. But that is explicitly why we started the two projects. And the healthcare providers we worked with actually found it quite appealing that we were not weighed down by the conventions of the healthcare sector. We first got into the topic in a very strategic way, but then it expanded into a completely new domain to explore, which took us much further than we had expected. There are huge constraints in designing a hospital, but the more constraints we encountered the more it inspired us to continue with our research.

You also made a film in which you analyzed the situation in healthcare before the pandemic. One of your conclusions in the film is that “healing became a matter of efficiency”. What do you mean by that?

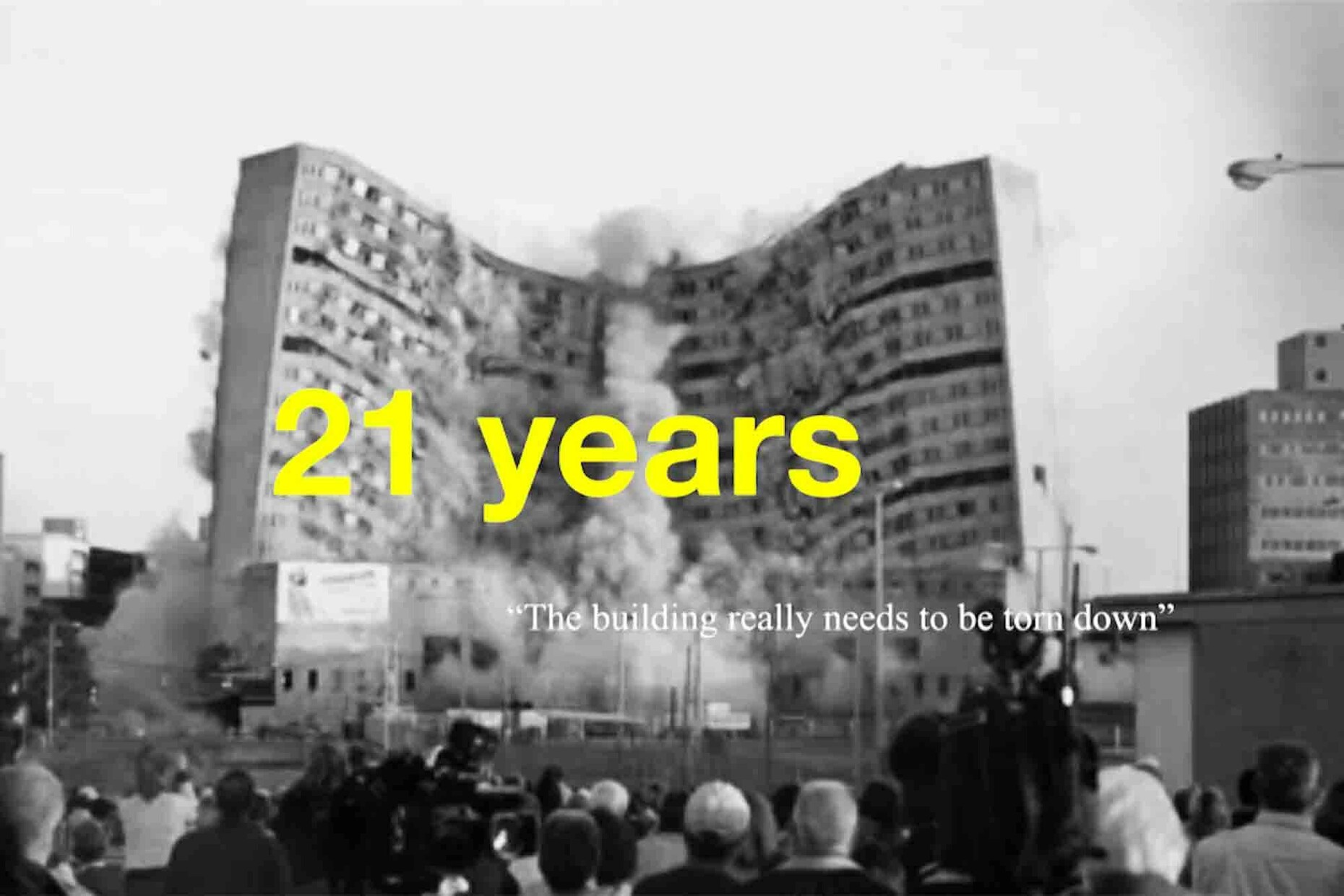

Alex Retegan: Over the last decades healthcare has slowly shifted from a public duty into a form of business. As a result, everything has been quantified and viewed through the lens of efficiency, whereby efficiency in this case really means profitability. The consequence has been a largely privatized sector that tries to cut costs and seeks to get rid of everything that doesn’t earn money. That is perfectly illustrated by the number of hospital beds today. After the 1990s, almost every country in the world experienced a dramatic reduction, especially Europe and North America. In the Netherlands for instance, the number of hospital beds dropped by 45% between 1990 and 2018, same as in the US. Then came the pandemic and it became evident that there isn‘t enough space in hospitals for patients.

So it became evident that this is a vulnerable system. What has changed since the pandemic?

Hans Larsson: There is more awareness but when you talk to healthcare consultants after one year of the pandemic, it’s still the same discourse that healthcare is too expensive.

What could architects do to solve this?

Hans Larsson: Money and architecture are obviously closely linked and as an architect you can only work with the budget you have. We found it interesting to analyze how money can be translated into the infrastructure that a patient needs in a hospital. If you look back at the hospitals built one hundred years ago, they owned not only buildings but also fields and forests. In Paris, for example, the AP-HP (Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris) used its property to produce firewood and food for its patients. We were very inspired by that approach, which is not just about a building but a whole system. While some might argue that it is a nostalgic vision, in this case we embrace the nostalgia nevertheless.

This is a very infrastructural approach. You mentioned that the pandemic has made people realize there isn’t enough space in hospitals. It seems to me that this is also an architectural problem and a problem of spatial flexibility.

Alex Retegan: The idea of spatial flexibility has been there since the beginning of hospital design. The question, of course, is how it has been addressed. Most of the hospitals that are in use today date from the late post-War period. They were designed with their own idea of spatial flexibility, which came in the form of the tower-socle configuration. All the clinical facilities were in the socle and could be reconfigured as needed, while the patient rooms were in the tower. But the standards for patient wards also changed, and there was little that could be changed in the tower itself as it could only expand vertically.

What is your solution to gain spatial flexibility?

Hans Larsson: I think that any specific answer is doomed to fail because of unforeseen changes in the organization. Nonetheless, we believe that there are solutions. As you already said, our approach is more related to city planning and the idea that the hospital must become part of the urban fabric whereby you provide a flexible healthcare infrastructure. One idea is to use 3D printing to customize design in a much faster way. In combination with a typology that doesn’t go vertically but spreads itself horizontally, we could imagine various zones that are indeed more flexible in their reconfiguration.

Could this also lead to a more ephemeral approach in hospital architecture?

Hans Larsson: Yes, exactly. Temporary architecture like the Cineroleum in London, a project by Assemble that transformed a petrol station into a cinema, are a good example for this, but so are field hospitals with their rapidly-deployable units. Flexibility also means mobility. During the pandemic we have seen how important it is to maintain mobility as one place is more affected by the virus at one point and then others are.

Another quote from your film is that “the hospital of the future will take your order – like a logistics center sorting and sending”. Could you elaborate on this?

Alex Retegan: The reality is that no one really likes to go to hospital. So we asked the question, How to avoid having to go to it in the first place? Perhaps the hospital could host an array of services and products that can be delivered. As we said before, this also means that the hospital could be a productive unit, which works more self-sufficiently.

Hans Larsson: We all know that Amazon is a problematic entity for various reasons. But if you would use the model of Amazon in the interest of public health, suddenly a lot of the devices could become unexpected virtues because you can provide healthcare much more quickly. This is not to say Amazon should become a healthcare provider. It means that healthcare providers can learn from Amazon. In the US, Amazon has an algorithm which automatically arranges the stock of goods depending on the climate. What if a hospital network had the same algorithmic approach, locating their medical goods where they are most needed?

Alex Retegan: In the West everything tends to be well inter-connected. You don’t necessarily notice a shortage of medical goods. But other parts of the world aren’t connected that well to the global network. It is there that it becomes even more urgent to rethink the dependency on the logistics.

When I did the preparation for this interview I became aware that robots are already a part of the logistics of a hospital. I guess you also address this in your film when you say that “the hospital of the future will give way to the machine – liberating its staff from routine tasks and leaving precision in the hands of accurate devices.”

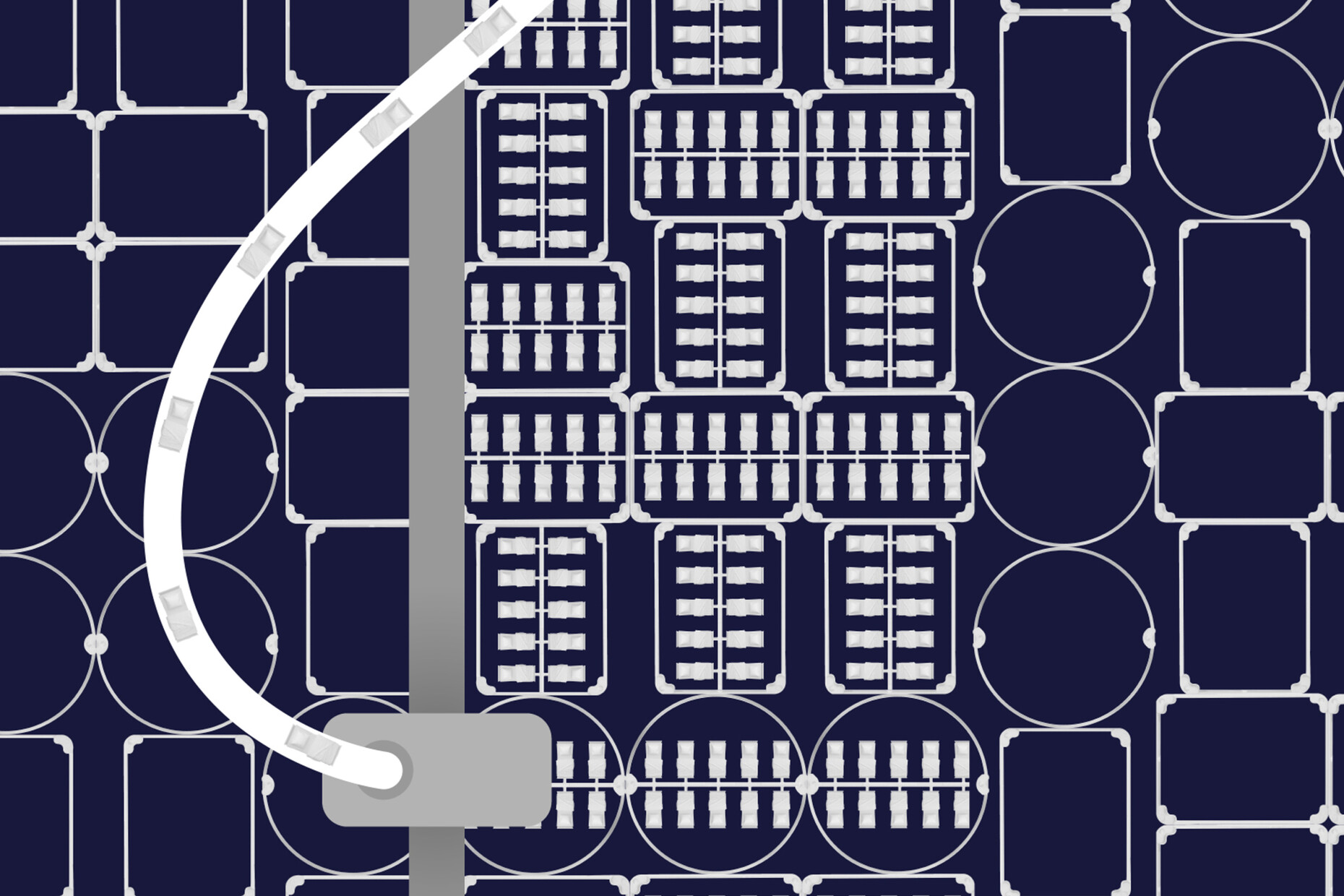

Hans Larsson: When you think of a hospital, you think of a corridor. There is a lot of space for transport and logistics. It’s a bit of a labyrinth. What robots or machines could bring in is that you could create two levels of infrastructure: one where you have a streamlined communication system inhabited by machines and one for the humans with a more sunlit and pleasant environment. In some Danish hospitals you can already see this being adapted. Yet, as a typological exercise, it could be taken much further.

Alex Retegan: Although there are robots in hospitals they are still treated like ‘guests’ because they cohabit spaces that were not designed for them. So, the idea is to include robots in the brief for the building. It might be an unpleasant thought to design a healthcare building for machines but ironically the end result might be more human.