In the footsteps of Schinkel

It performs its duties discreetly, Alexander Schwarz says of the new James-Simon-Galerie, which he designed together with David Chipperfield. That may seem a little surprising for a structure that has so many functions to serve. After all, not only is it intended to be the befitting new entrance to the Museumsinsel; it also houses the main ticket office, a large auditorium, a museum café and a new, very spacious bookshop. And actually, one understands immediately what Schwarz means, as visitors only register these “duties” en passant. They do not force themselves on them. And there is more: In some ways the James-Simon-Galerie also performs its duties as an edifice extremely discreetly. If you look at it from the Kupfergraben arm of the River Spree, it appears to consist mainly of a delicate colonnade, which rises like a pedestal above a high waterside wall. By way of contrast, from the entrance side, the James-Simon-Galerie seems to primarily comprise a vast, very deep set of steps. Almost the entire volume of the building is concealed behind these sweeping steps. And in fact there is almost no one view that reveals the entire size of the edifice. It is as if it were made for the most part of pillars and steps.

The interior features neither a large hall nor a monumental reception area. Instead there are two foyers – a lower one at street level and an upper one at the end of the large set of steps, both of them, in essence, passageways. The lower foyer, which is reached via a colonnaded courtyard between the James-Simon-Galerie and Neues Museum, leads visitors directly to the extended staircase, which forms the center of the structure and is a reprise of the steps outside. The inner structure of the building is geared to it. The upper entrance also immediately takes visitors to the top of this staircase.

The promise of light and lightness, the almost immaterial nature of the spaces suggested outside by the colonnaded walkway over the Spree is not, however, fulfilled on the inside. Not all functions can be concealed so discreetly for the character of the interior not to remain tangible here as well. But perhaps Chipperfield and Schwarz never intended the external and internal perception of the edifice to coincide. Their design works like a collage, just as it plays with measures and proportions – in the case of the stairs, for example, which would be totally oversized, were the Galerie not to be standing in the context of the other buildings of the Museumsinsel. These too are the means Chipperfield and Schwarz employ to navigate the dangerous waters that are inevitably lurking in any formal reference to Neoclassicism. The boundaries between Schinkel's heir and Speer's heir are quickly blurred. Through these breaks they undermine pathos.

The legacy of the Neoclassicists

It goes without saying that with the colonnade motif, which the architects made their main design medium, they reference the portico that Friedrich August Stüler created around the Alte Nationalgalerie and along what is nowadays Bodestrasse. The James-Simon-Galerie now continues it as far as Kupfergraben. A portico featured in the very first plans for the Museumsinsel, which Stüler drew up together with Frederick William IV of Prussia. As with the construction of the temple for the Alte Nationalgalerie, in the plans Stüler quotes what is even today the most influential example of imaginative German architecture – Friedrich Gilly’s 1796 design for a monument to Frederick the Great. Standing on a high pedestal, Gilly’s temple, whose surroundings are likewise enclosed by a colonnaded walkway, is a cenotaph and shrine to the Prussian king – but also a belvedere intended to give visitors an extensive view.

Karl Friedrich Schinkel repeatedly takes up the idea of a temple as a vantage point in his work, for example in his design of an enormous summer palace in the Crimea for the Russian czarina – and like Gilly he linked the temple to an accompanying colonnaded walkway. In the case of Glienicke Palace just outside Potsdam, he created a rotunda known as the “Große Neugierde” (Great Curiosity), as a vantage point pavilion from which to view the nearby bridge across the River Havel.

The idea of timelessness

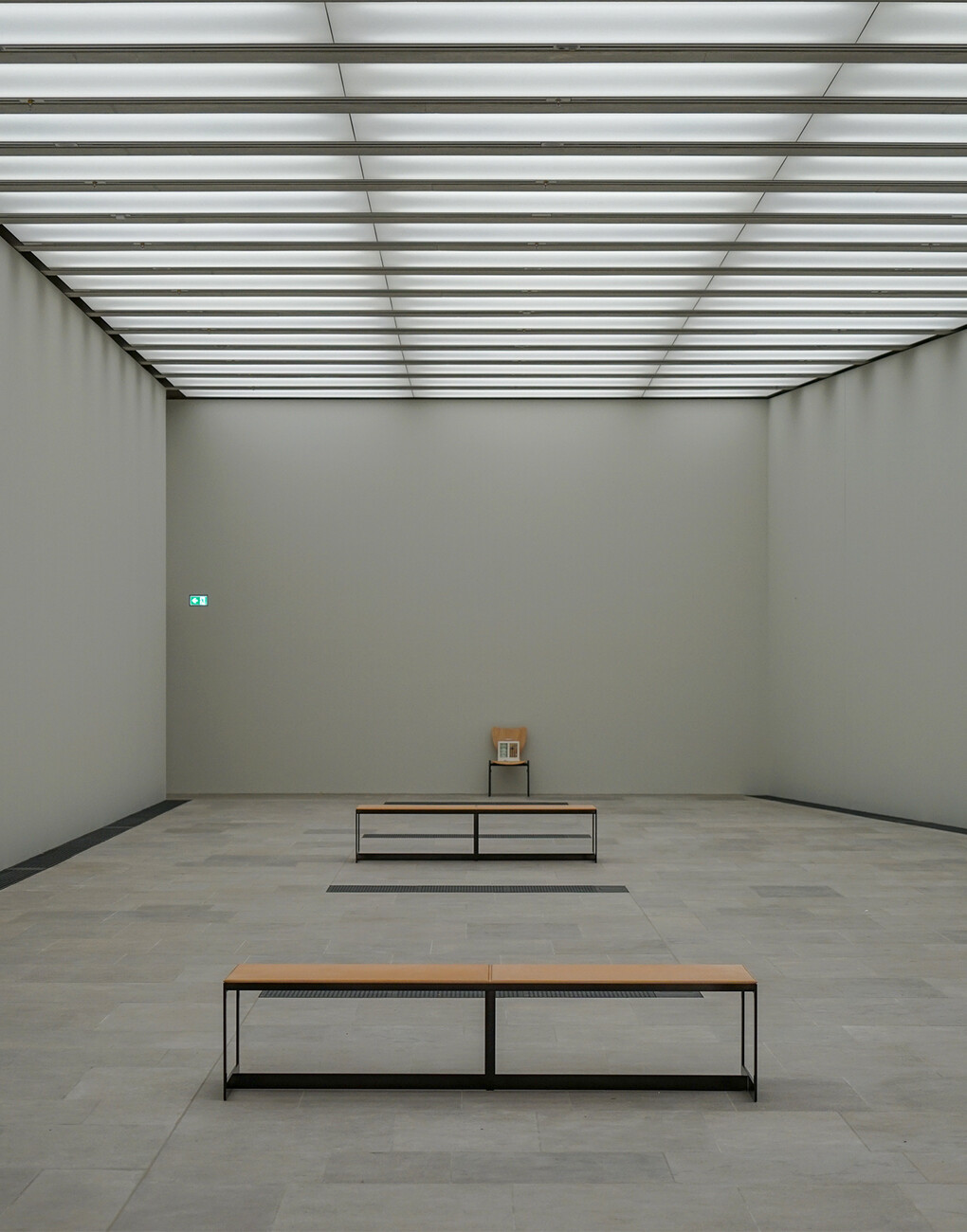

In their museum building, David Chipperfield and Alexander Schwarz bring together the two motifs of belvedere temple and colonnades. The two typologies meld here. The pillared structure along the River Spree not only references the colonnades of the Stüler structures. Indeed, at its open end the architects round it out with six columns like a temple porticus. It is a colonnade and belvedere temple in equal measure. The vantage point and the path leading to it become an uninterrupted flow of movement. With their sensitive and knowledgeable design, Chipperfield and Schwarz adopt a clearly opposite stance to the approach pursued, for example, by Bjarke Ingels and his BIG studio. They oppose a concept that sees the design process as serving the maximization of benefit. The James-Simon-Galerie unmistakably represents an all-embracing artistic level that extends as far as the wonderful benches the studio designed for the structure.

The addressing of German Neoclassicism in general and Schinkel in particular puts the James-Simon-Galerie in a tradition with the Neue Nationalgalerie at Berlin's Kulturforum and the Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart. Like Mies van der Rohe and Sterling, Chipperfield and Schwarz are looking for the timeless in architecture, the synthesis of classical and modern shapes. The result is a reflection on the particular location on which this edifice is built and its function as an entrance structure. But it is just as much an attestation in stone of respect for the architects of the Museumsinsel.