Architecture without walls

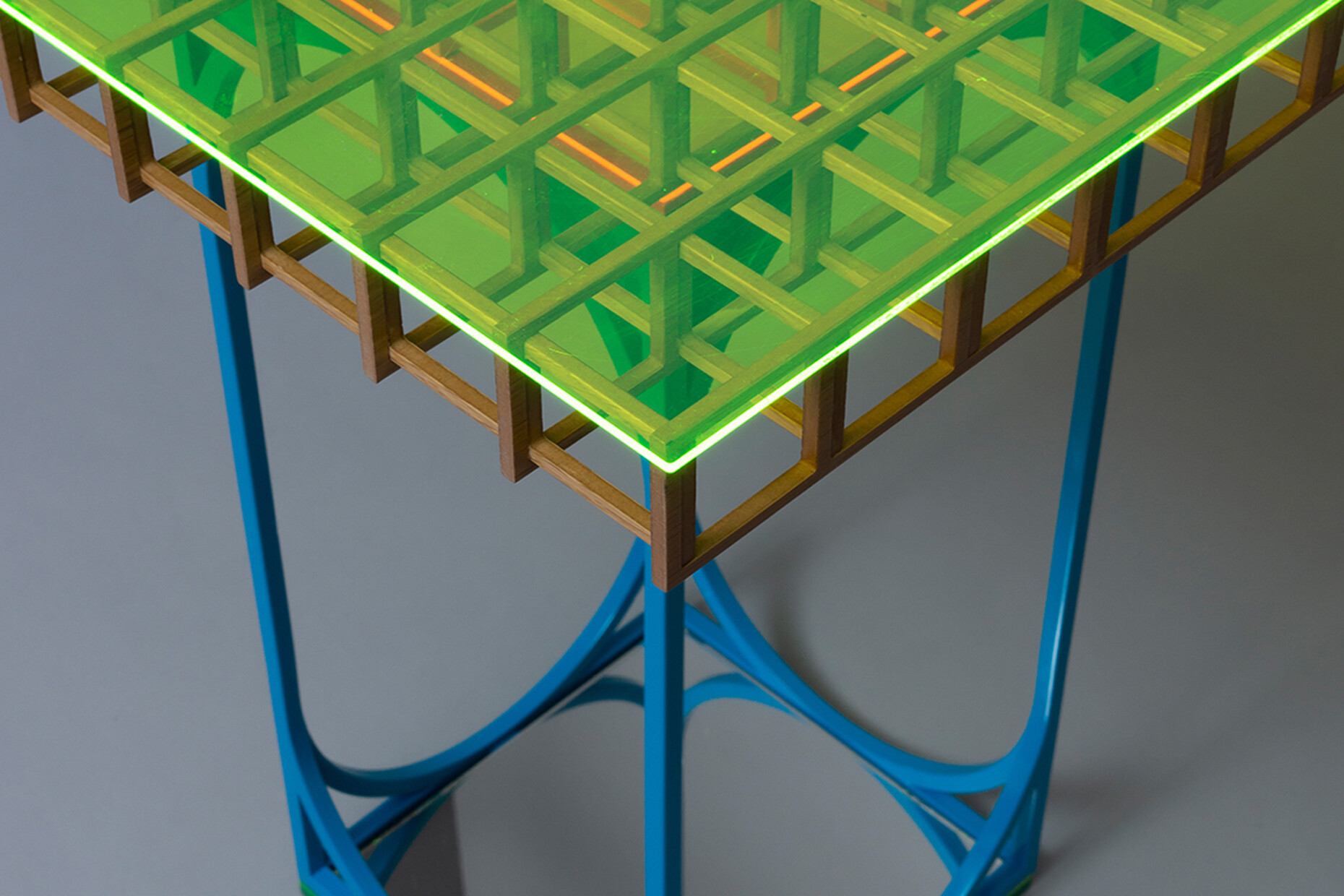

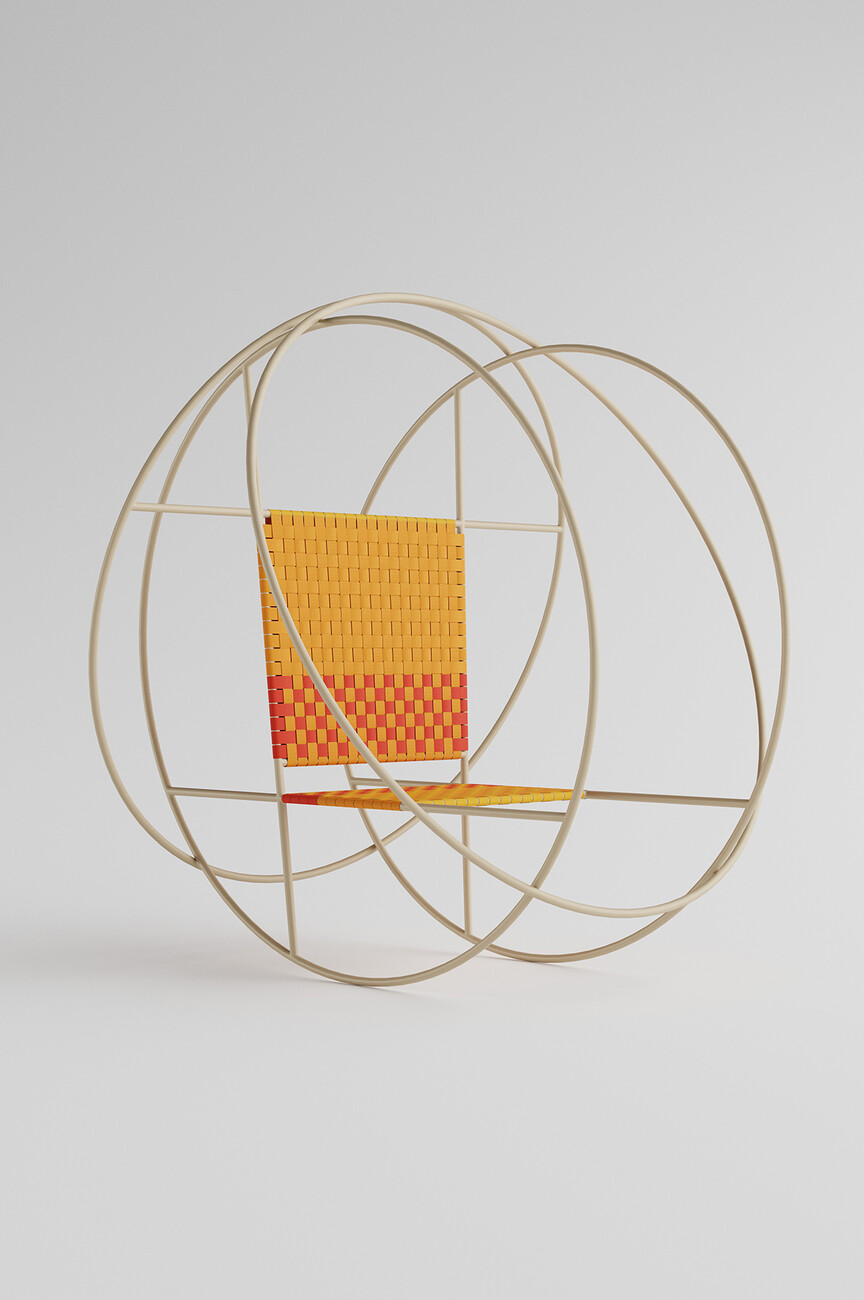

Kevin Hviid does not distinguish between architecture and design. Scale, in his practice, is secondary. “A chair can hold a room; a room can stage a chair,” he notes. What matters is how an object behaves in space. Architecture is not a discipline he switches between, but a way of thinking that applies at every level. This way of thinking explains why Hviid’s work moves fluidly between furniture, lighting, art pieces and spatial installations. He does not begin with typology, but with effect. What should an object do to a room? What should it do to the people inside it? Curiosity, touch, pause.“If I can draw it perfectly from memory, it’s probably already out there,” he says. His task, instead, is to widen the visual palette, even when the commercial “yes” does not come immediately.

Although based in Copenhagen, he resists being read through a single national design tradition. References enter his work through observation and handling rather than citation. “If I don’t understand an object, I touch it, take it apart, and rebuild it.” Cheap plastic fans from Tivoli once became a visual archive after their function was removed. Months later, their geometry resurfaced in an art piece. The original object disappeared, its visual attraction remained.

Play is central to this process, but never decorative. For Hviid, play is a working method; a way to avoid imitation and move beyond solutions that feel too safe. “Play isn’t decor. It’s direction,” he explains. He deliberately moves toward uncertainty. A model that feels unresolved late at night can suddenly make sense the next morning, when daylight hits it at a precise angle. The challenge then becomes translating that brief moment into something durable and repeatable.

This attitude also defines his understanding of function. Works such as the "Bob" bench are sometimes associated with Memphis – not as an aesthetic reference, but as a position that questioned strict functionalism. “I don’t fight form follows function – I expand what function includes.” Which, in his work, also is posture, emotion and presence. Objects can support a body, protect it, or quietly assert themselves in a room. For every piece, the goal is character.

The same thinking carries into commissioned work. Designing for brands such as Atbo, for whom Hviid created the "Cocoon" dining chair, introduces clear constraints: ergonomic, technical and commercial. Rather than limiting the process, these boundaries sharpen it. He begins openly, disruptively, and allows restriction to refine the idea. A production error that interrupts a curve can become a defining feature. What begins as an accident is absorbed into the design language and turned into intention.

Across different typologies, his work remains connected by sculptural clarity. A lamp like "Trit" and a bench like "Bob" operate at very different scales, yet follow the same logic. Hviid starts with a form that cannot be ignored, then finds the position that does it justice. Lighting reveals its place through movement, seating reveals itself through use. Circulation, voices and pauses become feedback. If the work becomes recognizable, he insists, it should be through rigor rather than repetition.

Looking back, Hviid describes his practice as an accumulation rather than a rupture. The language has grown more layered, more confident, yet its foundations remain intact. Some projects are understood immediately. Others require time. Expanding perception, he believes, is a long-term commitment: "This piece will make sense here in three years – but I’ll install it now anyway.”

Today, Hviid sees his studio as a space one can enter. A practice that takes play seriously through craft, precision and attention at every scale. In increasingly loud environments, some objects may appear too calm, too quiet even. But when they slow people down, that calm becomes value. As he puts it, the pause becomes the point.