Pushing the Limits

Entitled ole scheeren: spaces of life, the show documents his work and with the help of augmented reality offers visitors direct insights into both the urban and interior spaces of his buildings. We spoke with Ole Scheeren about the exhibition as well as about his work as an internationally active architect.

Alexander Russ: You positioned yourself internationally very early on, i.e. you studied abroad, worked at OMA in Rotterdam and then founded your own office in Beijing in 2010. In the meantime, you have offices in Hong Kong, Berlin and London. At the moment, the world seems to be moving away from globalisation. What's your take on this?

Ole Scheeren: That's an interesting and very complex question. Indeed, the world is no longer the same. I am certainly an extreme example of what's possible when you believe in international cooperation. After all, over the past 20 to 30 years, it wasn't just about having business relationships all over the world, but about being able to learn from each other, work with each other and go to other places to see what's possible there. For me, it's always been important to become a part of the culture in which I'm living and working. But despite all the difficulties that exist, especially on the political level, I still believe that working together is more productive and interesting than isolation. Of course, globalisation has created problems. For example, in that specific answers have acquired a general validity. And as a result, the respective solutions have become more and more similar.

Another argument in favour of globalisation has always been that it could trigger democratisation processes in authoritarian regimes. How would you assess that from today's perspective?

Ole Scheeren: Of course, as an architect you always have to take a close look at the context in which you're working, as well as what correlations there are. The related questions and problems are often so polemicised, however, that they don't do justice to the social and political complexity. The development of individual countries is not a linear process, and this also applies to globalisation. We're all part of this dynamic.

What effect does this dynamic have on your work?

Ole Scheeren: My office structure is a kind of reflection of globalisation, because, as you mentioned, there are offices in four different places. In addition, there's a very collaborative structure with staff distributed all over the world. This means that the individual offices are not independent satellites, but work together on the respective projects. It's also very important for us to be as close as possible to our projects. Our model has proven to be very crisis-proof and efficient. We often work on large projects, but we're basically a very compact office with about 100 employees. Other offices that handle similar projects are many times larger. Our size allows us to be very agile and means we can react flexibly to the situation at hand.

In a recent interview with the newspaper Die Zeit, the American economist Kenneth Rogoff predicted an end to the Chinese model of growth. One of the reasons he gave was the real estate sector, the growth of which is slowing down because the country is now overbuilt. How do you see this as an architect working in China?

Ole Scheeren: Predictions about China are often incorrect. This has to do with the fact that it's a very complex country that's seldom easy to understand from the outside. My work as an architect has given me certain insights in this regard, and I would say that China is quite capable of developing strategies that are designed for a longer period of time. To give you an example, ten years ago it became clear that Shenzhen could no longer be the world's sweatshop, where cheap production takes place. That's why there was a reorientation towards creative business and today Shenzhen is one of the world's great tech metropolises. We're now building two big office buildings there. But it is true to a certain extent; between 2000 and 2010 China's economy was very much shaped by the boom in the real estate sector. But the country is well aware of this. And because China is very much a part of the global structure, when the world isn't doing well, it's also felt in China.

One of your current projects is the Wuliang Interstice, a campus and culture experience centre for Wuliangye, one of China's leading wine producers. The project is very much about the history and culture of the place. Can you tell us more about it?

Ole Scheeren: The whole thing goes back to a competition and is a mixture of a museum for wine culture, a showroom and a hotel for visitors. The project is interesting, among other things, because wine is about cultural layers of time, and there are also agricultural aspects linked to it. The site is located directly on a winding river that has carved itself into the landscape. The existing topography has strongly influenced the design, which is why the new buildings take up the course of the river and thus represent an extension of the landscape. An interstitial space that's created in the process is to be landscaped in such a way that it provides information about wine growing and also becomes a place for storytelling. There are also some historical relics there, such as a pagoda, a Buddha sculpture and part of the old city wall. This is also part of the architectural concept, i.e. that visitors move spatially through the different layers of time while experiencing the place in a multi-layered fashion.

You opened an office in Berlin in 2015. What was the reason for that?

Ole Scheeren: It wasn't because of a specific project. I was more interested in integrating a location into our international office structure that had a certain potential – be it in terms of possible projects or implementing new collaborative structures.

One of your projects in Germany is the Riverpark Tower, a residential high-rise in Frankfurt am Main.

Ole Scheeren: What's exciting about this project is that it's a conversion and not a new building: a high-rise office building from the 1970s, centrally located, on the banks of the Main river. It dates from the Brutalist era, which is why a lot of concrete was used in its construction. There are eight columns near the corners of the building that support large, free-spanning concrete slabs. This made it possible to design continuous, 15-metre-long window fronts. At the same time, we restructured the core of the building and were able to gain an additional 2,000 square metres of living space. The design therefore deals with the question of how to deal intelligently with what already exists, in order to find a solution that goes beyond the banal addition of a new façade. In addition to addressing sustainability through the preservation of the basic structure of the building, we were concerned with creating high-quality living space. Sustainability is often only defined in terms of numbers, but if this doesn't result in quality architecture as well, then the whole thing will be a catastrophe.

You have a lot of large projects and high-rise buildings in your portfolio. How have you experienced building in Germany?

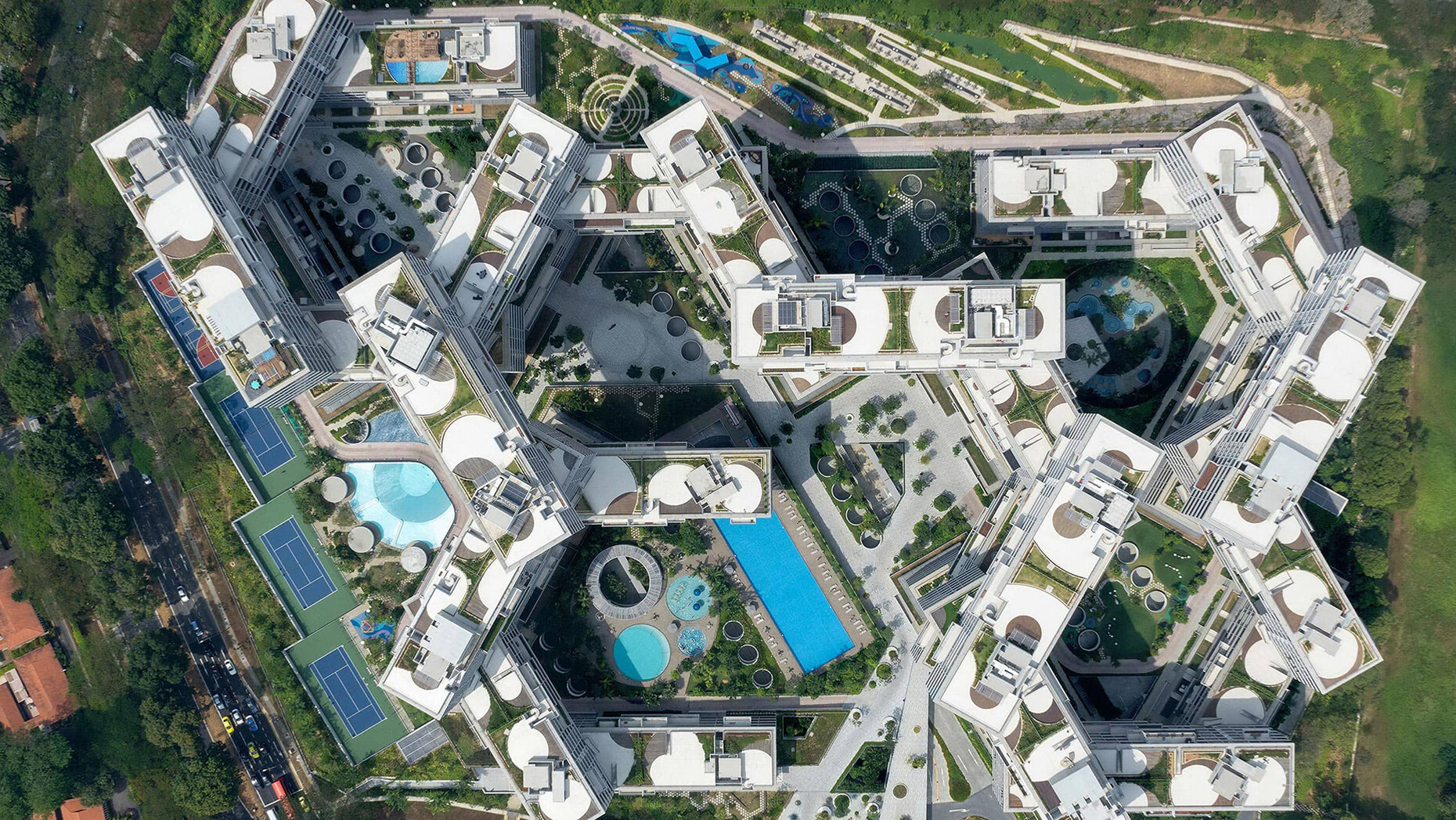

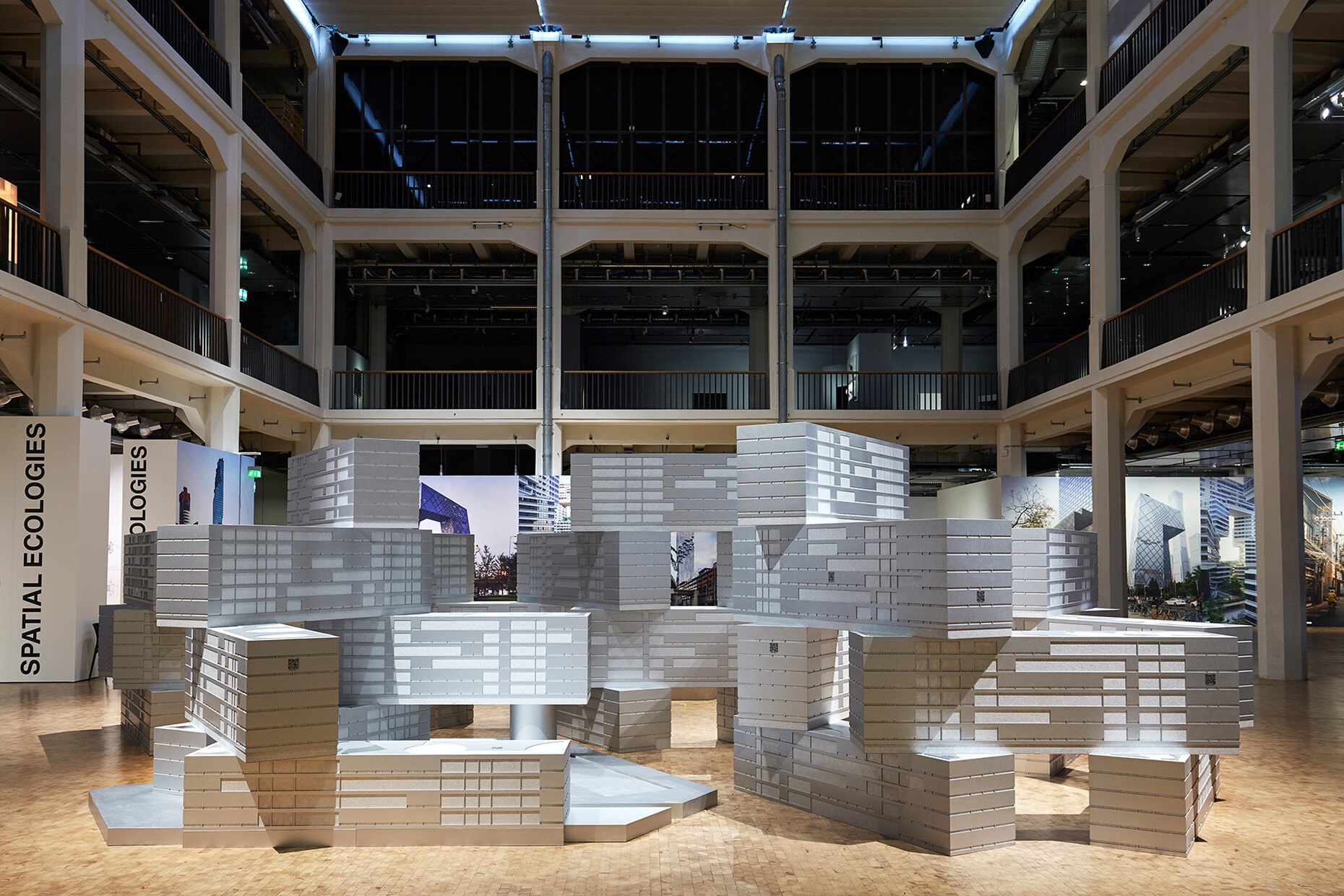

Ole Scheeren: We certainly have some large projects in our portfolio that were built on a scale that wouldn't be feasible in Germany. But we also have smaller projects, as well as projects that are structured horizontally rather than vertically. You can see this very clearly in the ole scheeren: spaces of life exhibition, which is currently on at the Centre for Art and Media (ZKM) in Karlsruhe.

And yet, people tend to perceive you as an architect who works on large projects.

Ole Scheeren: That is true, but I simply didn't feel the need to have every little project we have shown in the media, but wanted instead to focus on certain buildings.

An example of a small project is the Archipelago Cinema, a temporary floating cinema in Thailand.

Ole Scheeren: Yes, this is a project that really has the character of an installation. I've always enjoyed working with artists and filmmakers, and there are many other areas that interact with architecture. I'm very interested in these interfaces, which I think becomes quite apparent at the ZKM exhibition in Karlsruhe.

You originally come from Karlsruhe and also studied architecture there for a while. What does the exhibition mean to you?

Ole Scheeren: I always went to the exhibitions at the ZKM when I was a student. Recognising media as an art form was a very progressive perspective at the time and that interested me. During my studies I dealt with the relationship between physical and virtual space, among other things, and developed concepts that would probably be called co-living structures today. This is why the connection between media and architecture is addressed in the exhibition: There's an area in the centre that I call the “Media Dump”. Screens are placed there that randomly show everything on the internet that has to do with our work. Some of the buildings we've designed and built have a certain media presence. These are experiential spaces that are linked to people's individual experiences, and we wanted to show this link between media and architectural space at the exhibition. This has now become part of the reality of architecture.

ole scheeren: spaces of life

Until 4 June 2023

ZKM | Centre for Art and Media

Lorenzstrasse 19

76135 Karlsruhe

Phone: +49 (0) 721 810 00