Spotlight on Women Architects – Elizabeth Diller

In Venice, at the 2025 Architecture Biennale, she joined the ranks of the baristas. At the installation ‘Canal Café’, which her team had set up there, she served espresso brewed with lagoon water from the Arsenale harbour basin, which had been purified in four reed reactors. The installation encouraged visitors to engage with the ecological conditions of the lagoon city in line with the general theme of the Biennale. Diller Scofidio + Renfro, together with Aaron Betsky and Davide Oldani, won the Golden Lion for the best individual contribution. The commitment in Venice is no coincidence. Elizabeth Diller is one of the (few) architects in the USA who are committed to ecological architecture.

Diller was born in Łódź, Poland, in 1958. Two years later, her family emigrated to New York City. She studied fine arts, film and photography at Cooper Union. A course taught by John Hejduk eventually led her to the architecture department, where she met her teacher, mentor and later partner Ricardo Scofidio (1935-2025). In 1981, they founded their joint office, Diller and Scofidio, and married in 1989. Charles Renfro (*1964) joined the office in 1997 and became a partner in 2004 of the team now known as Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R).

The Cooper Union, where architecture was practised by John Hejduk, Peter Eisenman and Daniel Libeskind not as a technical and economic profession but as a cultural genre linked to art and philosophy, also shaped Elizabeth Diller and led her to creative, conceptual, even rebellious approaches. "I never wanted to build. We considered architecture to be intellectually bankrupt and slightly corrupt, and I became increasingly interested in other forms of discourse," she says, describing her attitude at the time.

For many years, the studio focused on experimental and visionary designs that went beyond practical construction. When they finally turned their attention to actual building, ‘we were quite arrogant. But during our work as architects, we became very humble. It's really difficult to deal with budgets and deadlines and all these employees.’ Nevertheless, they initially stuck to their aspirations to question conventions, push the boundaries of architectural perception and think visionarily. This allows them to approach new tasks ‘naively’, initially without having the construction process in mind. She describes the process as ‘jumping off a cliff without a parachute, then figuring out how to build something for a soft landing.’

Diller's architecture is never merely the fulfilment of a building programme. It is always about unconventional concepts of architectural living space, new spatial experiences and social responsibility. The commitment to public space in the sense of a duty to users runs through the entire work of DS+R. "The task of architects is to secure as much space as possible for the public. If it were up to me, I would simply make the ground floor of every building accessible to the public. That would be fantastic for the democratisation of space," she says, casually addressing the cardinal problem of today's urban planning, which, in its quest for traffic optimisation and maximising floor space, has forgotten the people for whom the city is a place to live and act.

One of their best-known projects is the High Line, a former freight railway viaduct on the western edge of Manhattan, which was converted in several stages between 2009 and 2019 into a 2.7-kilometre-long, popular city park on level +1 and is now highly valued as a green public space. The High Line became a stage for human interaction. A place for new, changed perceptions and uses of the city – an enormous gain for the people of extremely densely populated Manhattan. DS+R's work in Moscow attracted international attention. They won a major international competition to design Zaryadye Park. It was built on a 14-hectare site next to the Kremlin and Red Square on the banks of the Moskva River, replacing the demolished Rossiya Hotel, and opened in 2017.

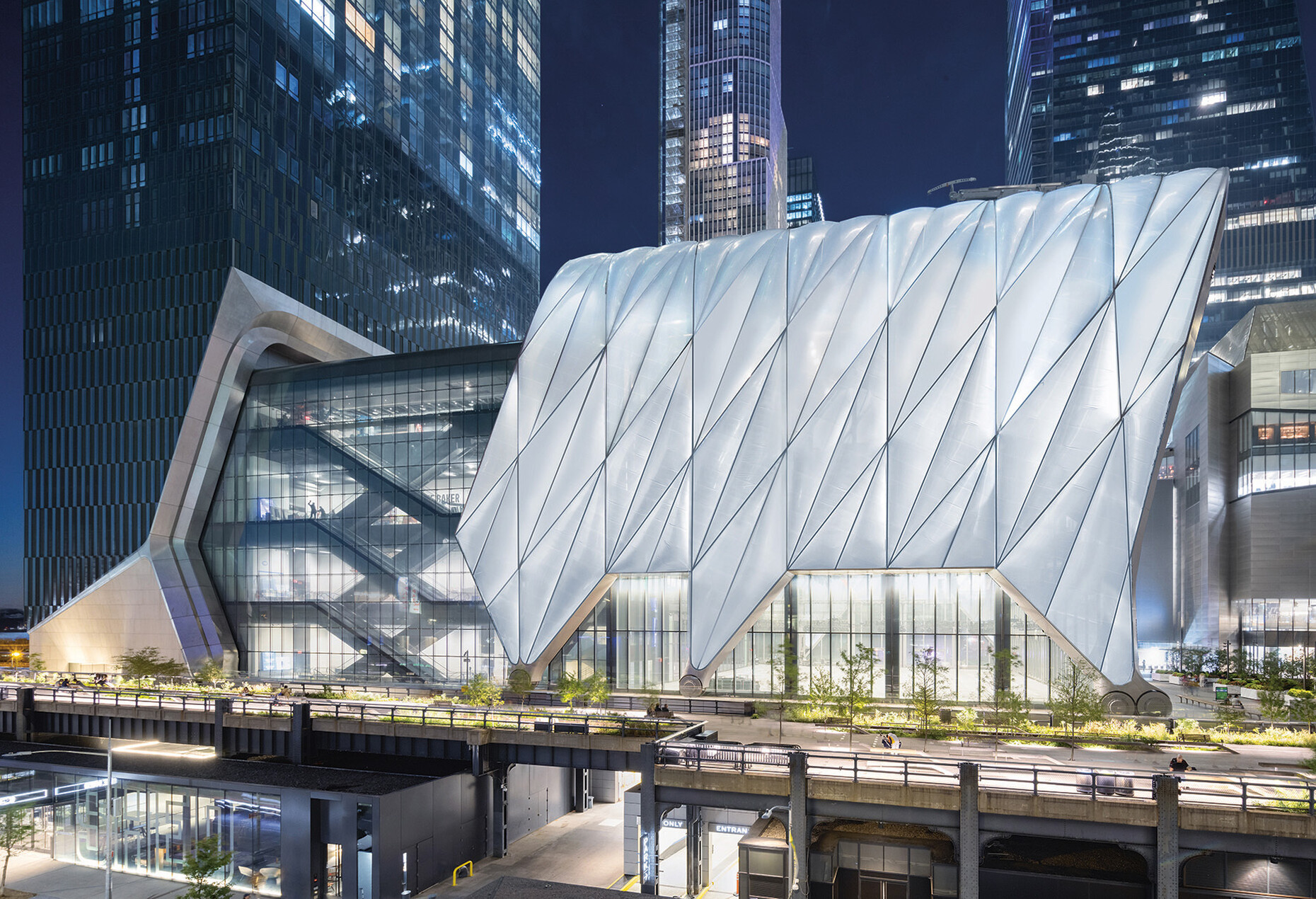

Diller's work is characterised by a deep understanding of the social and cultural context. She is never concerned solely with the aesthetics of the object, but always with the dialogue that architecture engages in with people and their environment. One of the constants in Diller's work is her desire to stage public space as a stage. A striking example is The Shed, a cultural centre in New York City at the end of the High Line (2009-2019), which stands out for its spectacular dynamic sloping shell, which stands on wheels and can be moved over an outdoor play area or over the building depending on the weather. The project also demonstrates Diller's interest in new technologies and her enthusiasm for technology, which repeatedly leads her to unconventional applications.

The architectural repertoire of Diller Scofidio + Renfro is dominated by two motifs in particular: Towering cubes shifted against one another stack up high, as in the Perry and Marty Granoff Centre for the Creative Arts at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, the David Rubinstein Forum at the University of Chicago, and the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston (2006), which impresses with a gigantic and structurally ambitious cantilever of the upper cube over the harbour basin. This unusual aesthetic sometimes gives the buildings a strong symbolic power and a decidedly iconic presence. One attractive eye-catcher, for example, is the Roy and Diana Vagelos Education Centre at Columbia University in Upper Manhattan. The south side of the 14-storey tower opens up to the viewer, revealing its inner workings: a cascade of lecture halls, seminar rooms, study rooms and staircases stacked on top of each other. Not far away and hardly less attractive is Columbia's Business School, whose stacked glass façade also turns the interior with all its halls and stairwells outwards – at least in the evening when it is lit from within. The two-part building is not without a certain drama, which is sometimes enhanced by the distortion of the stacked cubes in unrealised designs such as the Museum of Image and Sound for Copacabana in Rio.

The second recurring motif is structures raised at an angle from the horizontal. The Broad Art Foundation in Los Angeles (2015) is a cube clad in wild slats that appears to be raised at two corners to allow access to the interior. The United States Olympic & Paralympic Museum in Colorado Springs (2020) features an arrangement of four such sloping, floating cubes. Diller's early influence by conceptual design also explains his affinity for artistic interventions, theatre events, art and museum architecture. The Blure Blur Pavilion at EXPO 2002 on Lake Neuchâtel near Yverdon-les-Bains in Switzerland oscillated between the fields of environment, philosophy, art perception and spatial awareness. Diller responded to the quest for ever higher-quality, high-resolution images in a confrontational manner with a diffuse, contourless cloud the size of a football field floating above the lake. Water as a ‘building material’ dematerialised the architecture. 35,000 high-pressure nozzles sprayed a fine mist of lake water, which had to be purified by a filter system beforehand for health reasons. Diller's experiences with this technique were incorporated into the Canal Café project at the Biennale in 2025.

Diller says it's a shame that architecture is linked to a white, male hero type, pointing out that 50 per cent of architecture students are women, but only 20 per cent stay in the field. She sees herself as a beneficiary of the women's movement, even though she didn't do ‘the hard work’ of the emancipation movement herself. She sees her own professional practice with a diverse range of partners as emphatically inclusive and integrative.

In her teaching at Princeton University, New Jersey, she tries to pass on the experiences of her own studies and career, encouraging independent thinking and unconventional approaches: ‘I love not teaching what I know, but what I don't know. I throw students off balance and make them feel insecure.’ In doing so, she seeks to promote a way of thinking that always questions certainties and looks for alternatives. Elizabeth Diller has found a way to preserve this curiosity and unconventionality from her early days and translate it into truly great architecture.