Spotlight on Women Architects – Marlene Moeschke-Poelzig

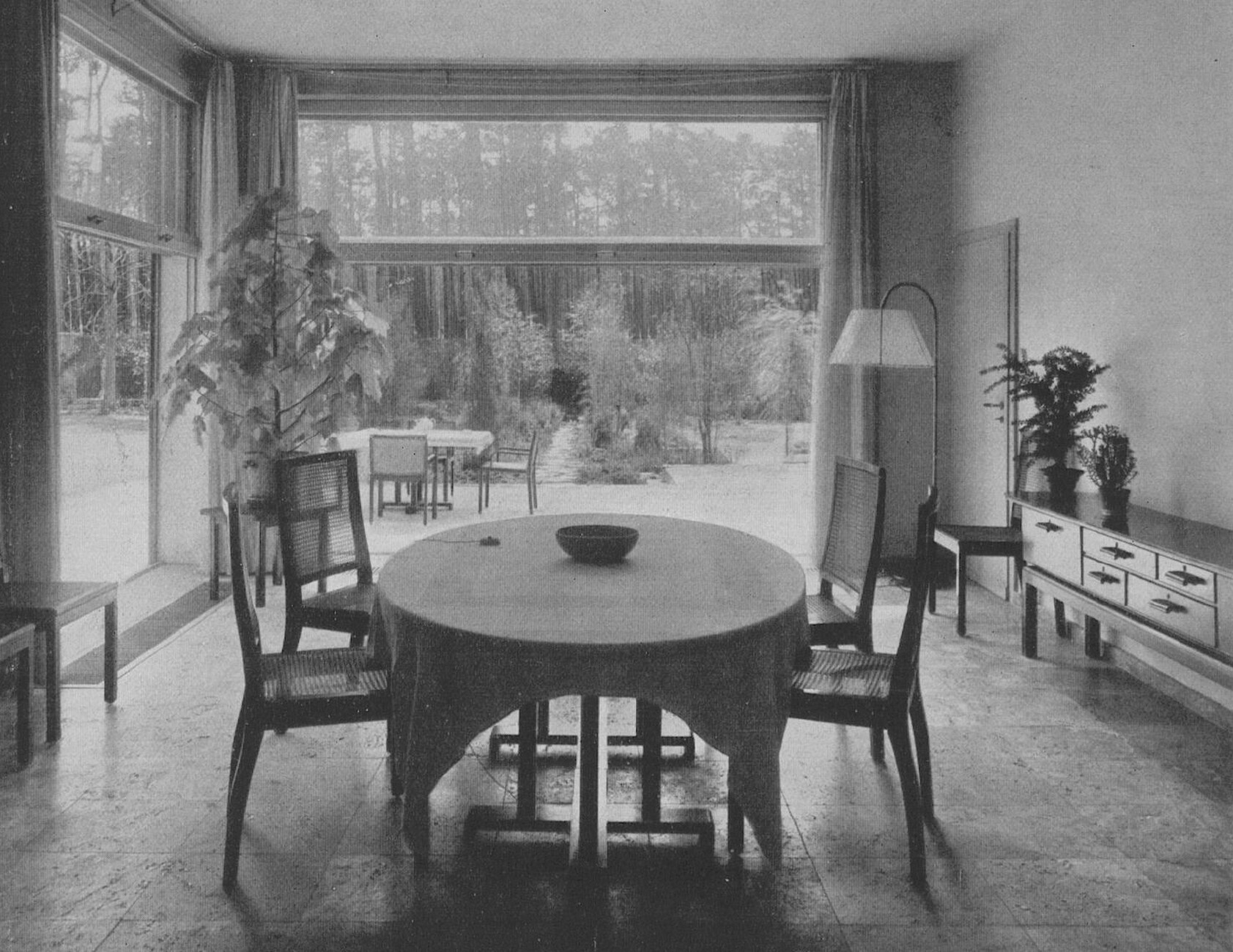

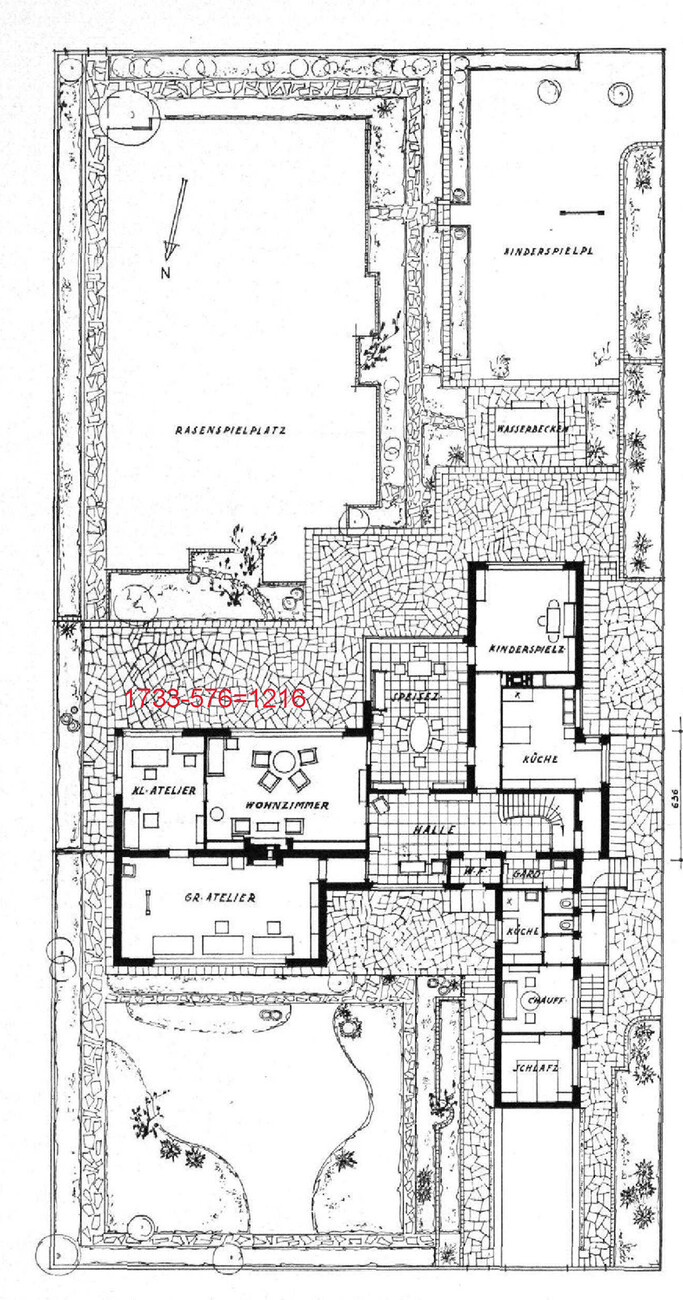

When the demolition crew moved in on Tannenbergallee in Berlin's Westend in November 2020, they not only removed a long-neglected single-family house to make room for new, lucrative property. They also erased an architectural testimony to Berlin's architectural history, as well as an object of identification for the growing movement of women architects who are no longer willing to accept male dominance in the profession. The plan had been to establish a museum and documentation center for women architects as well as a residence for scholarship holders in the spirit of Marlene Poelzig in the Villa Poelzig. After all, the Poelzig House, built in 1930, was not designed by Hans Poelzig, the most famous of the architects who did not belong to the Bauhaus circle, but by his second wife Marlene Moeschke-Poelzig. Then there was the garden, designed by none other than Hermann Mattern, who collaborated with his wife Herta Hammerbacher and Karl Foerster longtime resident of Potsdam’s Bornin district, who was known as the Bornim “Perennials Pope” for promoting the use of (flowering) perennials. The villa in Tannenbergallee demonstrated how such a house, which served both as a place of work and a private home, as a shared office, but also as a home for a family of five, needed to be organized from a woman's point of view: Consequently, the area for the three children was on an equal footing with the studio, and instead of the children's bedrooms measuring just eight square meters customary at the time the generous space available for play was considered more important than a prestigious office. Whether other buildings can be traced back to her plans is not known.

Born in Hamburg in 1894, Marlene Poelzig was a confident woman and highly charismatic. A sculptor and architect, from 1920 she and her husband ran the Poelzig architectural studio together. Working alongside her husband who was a brilliant designer, she shifted her own focus to furnishings and interior design. She was involved as an artist in the Haus des Rundfunks (Broadcasting House) on Masurenallee where she designed the striking chandeliers in the foyer. However, her major work in collaboration with her husband was the interior design for the conversion of the Schöneberg indoor market into Max Reinhardt's Großes Schauspielhaus in Berlin. Whenever the iconic images of the famous illuminated pillars in the foyer decorated with ornaments resembling stalactites go on show, it is Marlene Moeschke-Poelzig who should actually always be named as their mastermind and not Hans Poelzig.

Marlene mainly took on private commissions for residential buildings. “Buildings under three meters don't concern me,” Hans Poelzig once commented – and later upped the yardstick to ten meters. Layout planning and interior design were then her business. So, it was only logical that she should design her own house. “Contact my wife, the professor,” he informed a developer, “I have nothing to do with all that.” After Poelzig's death in June 1936, Marlene carried on running the studio. However, because Hans Poelzig was half-Jewish, the Nazis forced her to dissolve the studio in 1937 and she ceased working as an architect. She then sold the house and moved back to her native Hamburg, where she died in 1985. Her daughter Marlene Poelzig-Krüger, who worked as an astrologer for the Springer publishing house and served an upmarket clientele, is sometimes confused with her because she has the same first name. Marlene Moeschke-Poelzig's main architectural work, the Villa Poelzig, was radically remodeled, its appearance greatly altered, and its interior stripped of all period details. Despite its original significance and history, the building was no longer of interest to the Office for the Protection of Historical Monuments because of its lack of original substance. Preserving the building as Villa Poelzig would have involved extensive reconstruction, but this would no longer have been a matter for those engaged in heritage protection. The initiative that sought to preserve the building and use it as a center for female architects was unable to raise the funds to acquire the property, despite having well-known supporters, organizing demonstrations, and a procession with lanterns in front of the condemned building. It was therefore no longer possible to prevent the disappearance of the only testimony to the architectural work of Marlene Poelzig and a genuine source of reference for the architect. Today, she continues to live on in books and exhibitions, and is mentioned whenever the story of women in the architectural profession is retold.