Building with microbes

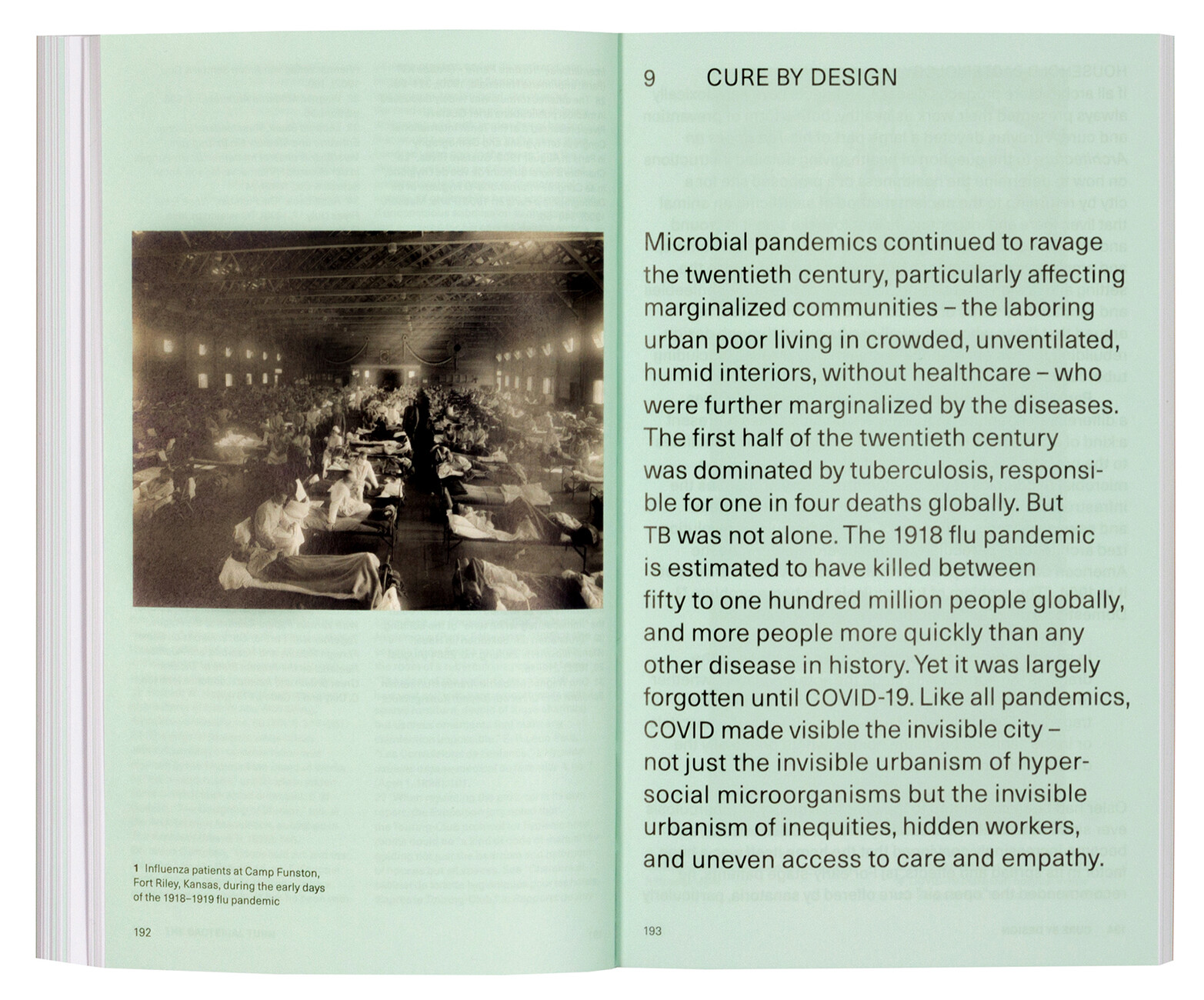

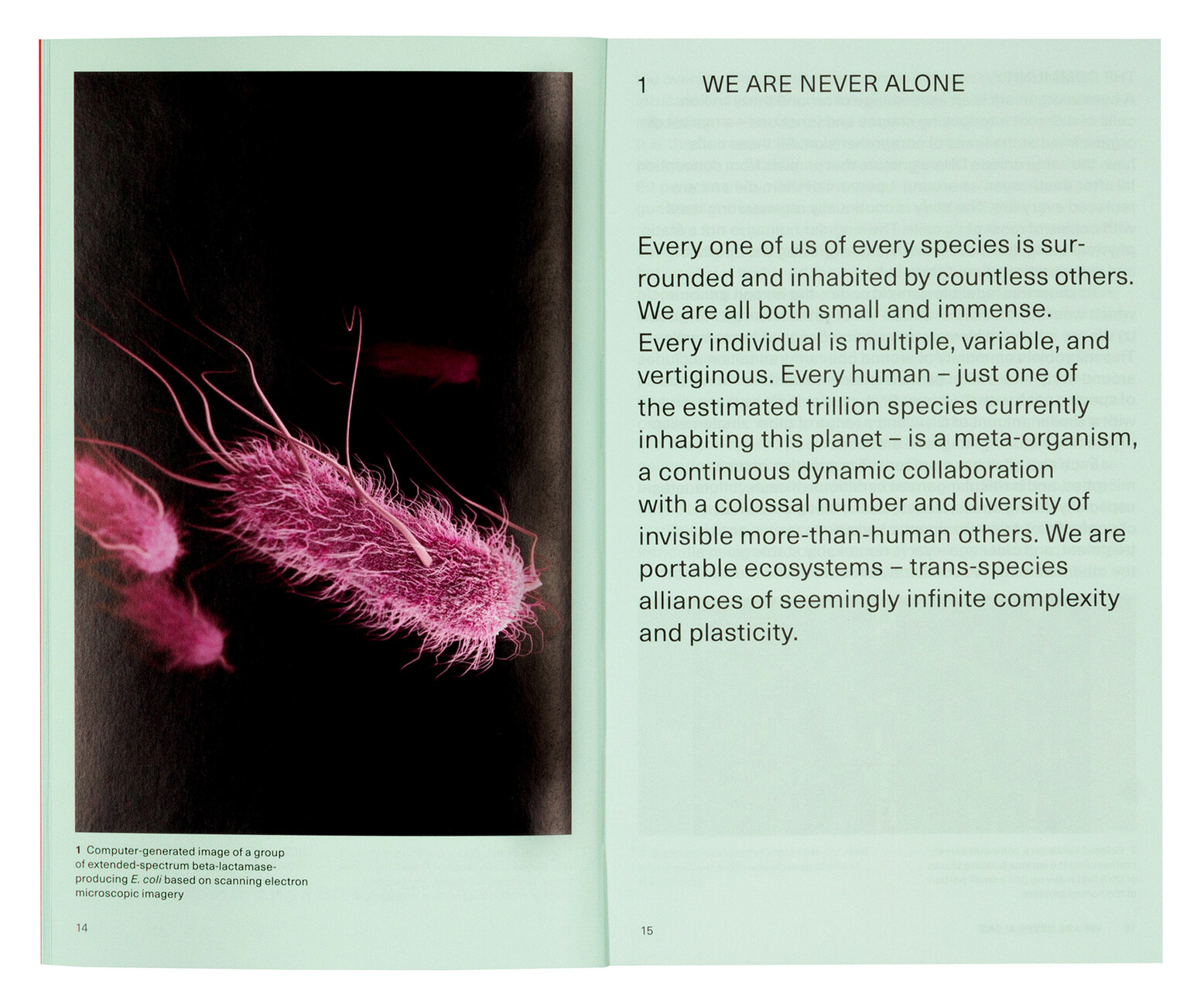

For “We the bacteria: Notes toward Biotic Architecture,” the two architectural historians delve deep into the microbial world, which Homo sapiens joined relatively recently, around 300,000 years ago. In the 352-page work, we learn that we are inhabited by many more microbes than human cells and that the highest density of microbes in the entire biosphere is found in the human colon. That the microbiome of the human intestine and that of the soil once developed together and that, with the creation of buildings and cities, we are essentially undergoing a kind of unconscious experiment in biotechnology, a genetic experiment to change humans. Architecture protects us from a variety of dangers, but at the same time promotes the spread of disease, as certain microbial communities cultivate themselves in rooms, on surfaces, materials, and systems, according to the authors. Thus, it is not humans who are the true designers of architecture, but rather the diseases to whose effects it has been adapted. “Modern architecture was explicitly conceived as an antimicrobial project—with the most influential architects and historians even describing themselves as bacteriologists.” Reflecting on the relationship between microbes and architecture, whether it be a building, a room, or a piece of furniture, also means grappling with the future of humans and countless other species.

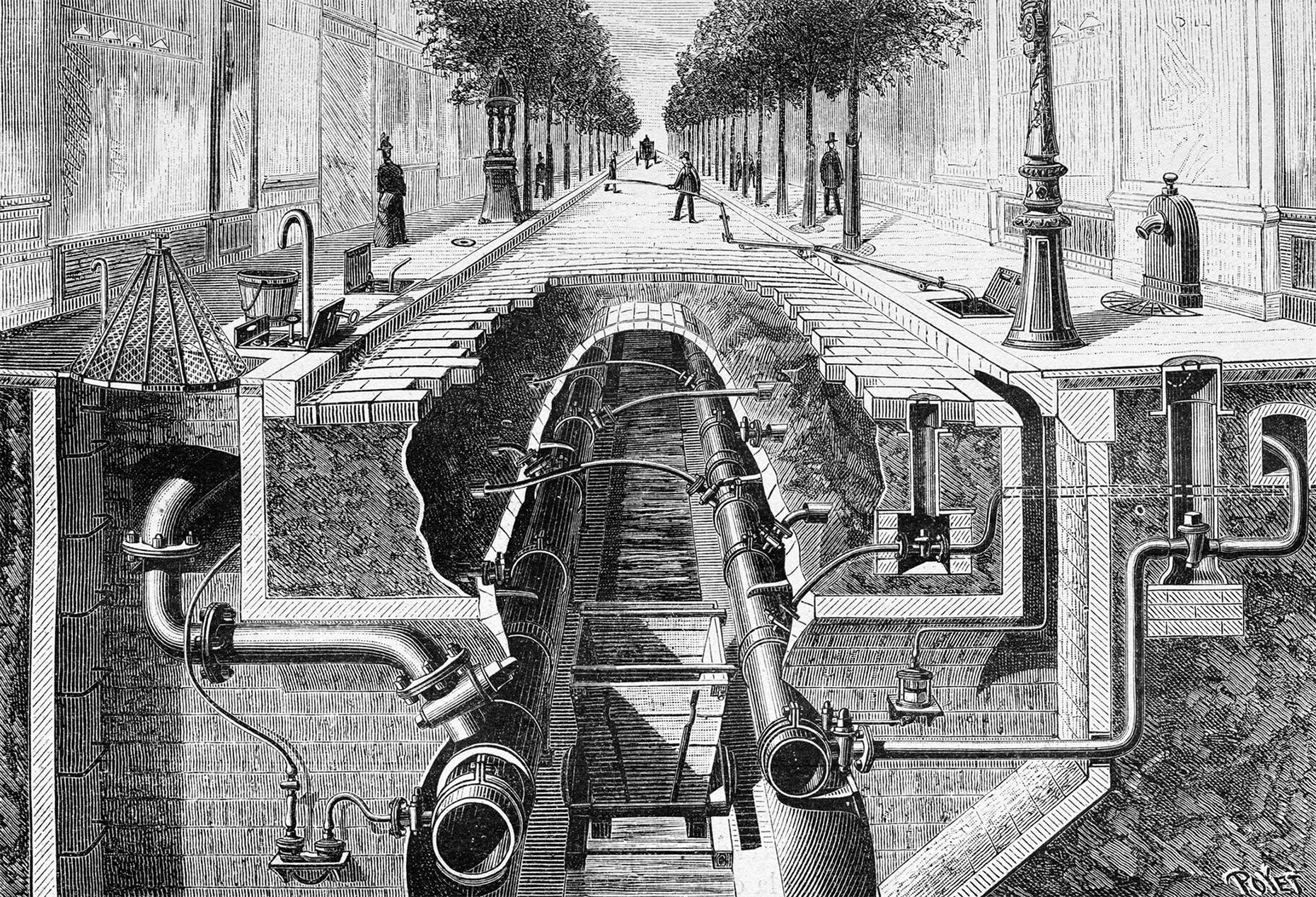

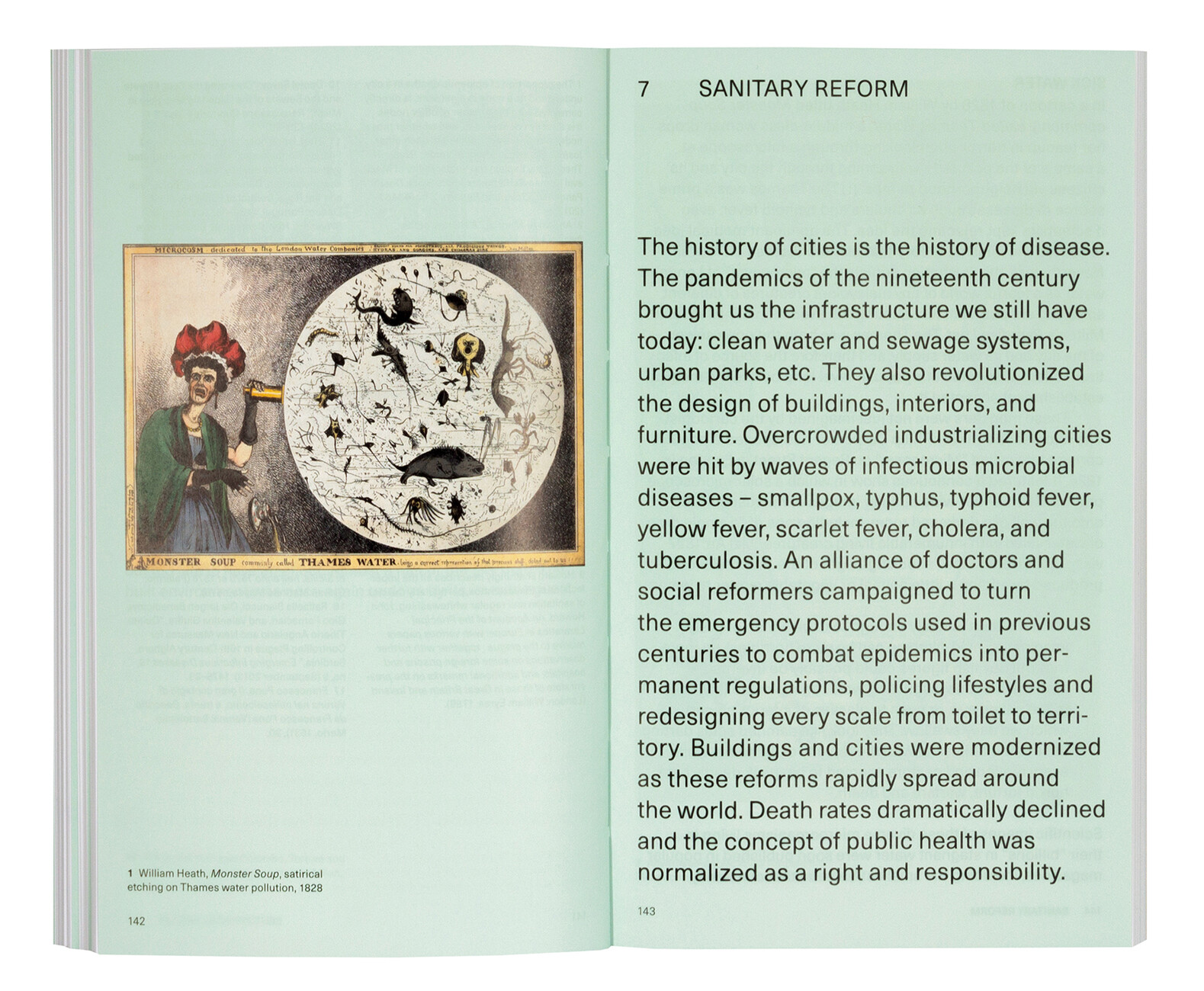

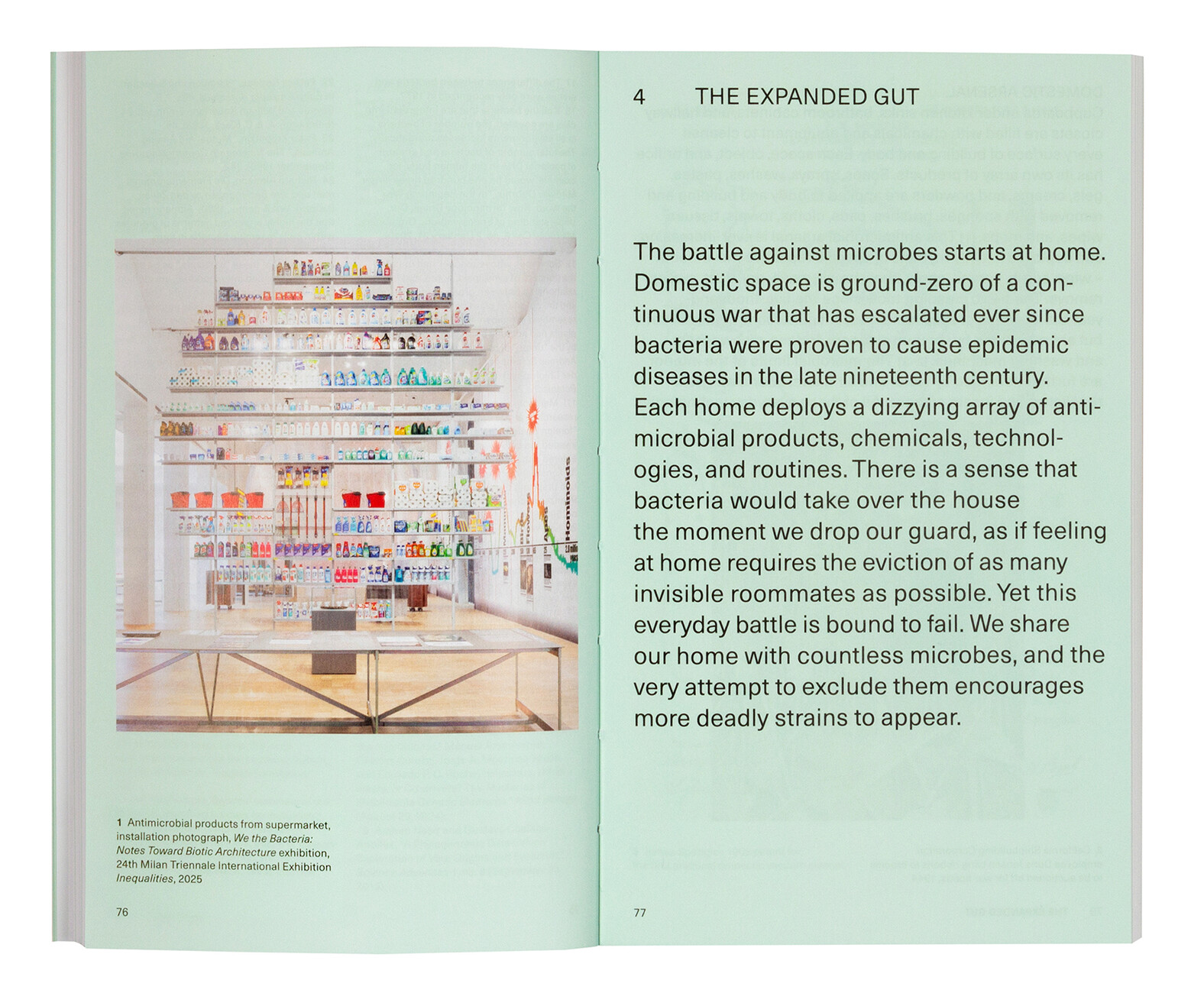

Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley have explored the relationship between disease and modern architecture in their interdisciplinary research. They explain how the reforms that emerged in industrializing cities as a result of the pandemics of the 19th century shaped our current infrastructure and how architects and designers oriented their designs in favor of hygiene measures. In the mid-19th century, for example, architect Edward William Godwin favored white walls and bright, airy rooms that resembled hospitals in their aesthetics. He dispensed with fabrics and moldings out of concern that dirt and thus pathogens could accumulate there. For the interior, he recommended minimal furniture, removable seating, minimal joints, no wallpaper, and easy-to-clean carpets. With the “White House,” which Godwin designed in 1878, he transferred the unadorned, disinfectable, and therefore hygienic aesthetic to the exterior with a white brick facade.

Dr. E. P. Léon-Petit also collaborated with architect Gustave Rives to design a “chambre hygienique,” a prototype hotel room intended to prevent the transmission of tuberculosis among guests. Starting with the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, the installation was on display at many trade fairs and conferences, contributing to the design of numerous hotels based on this model. We also learn that feminist writer and home economics pioneer Helen Campbell stated in House Beautiful magazine in 1899 that microbes were the most active promoters of progressive interior design: “Without them, the best forms of interior design would still be only a dream of progressive architects,” she said.

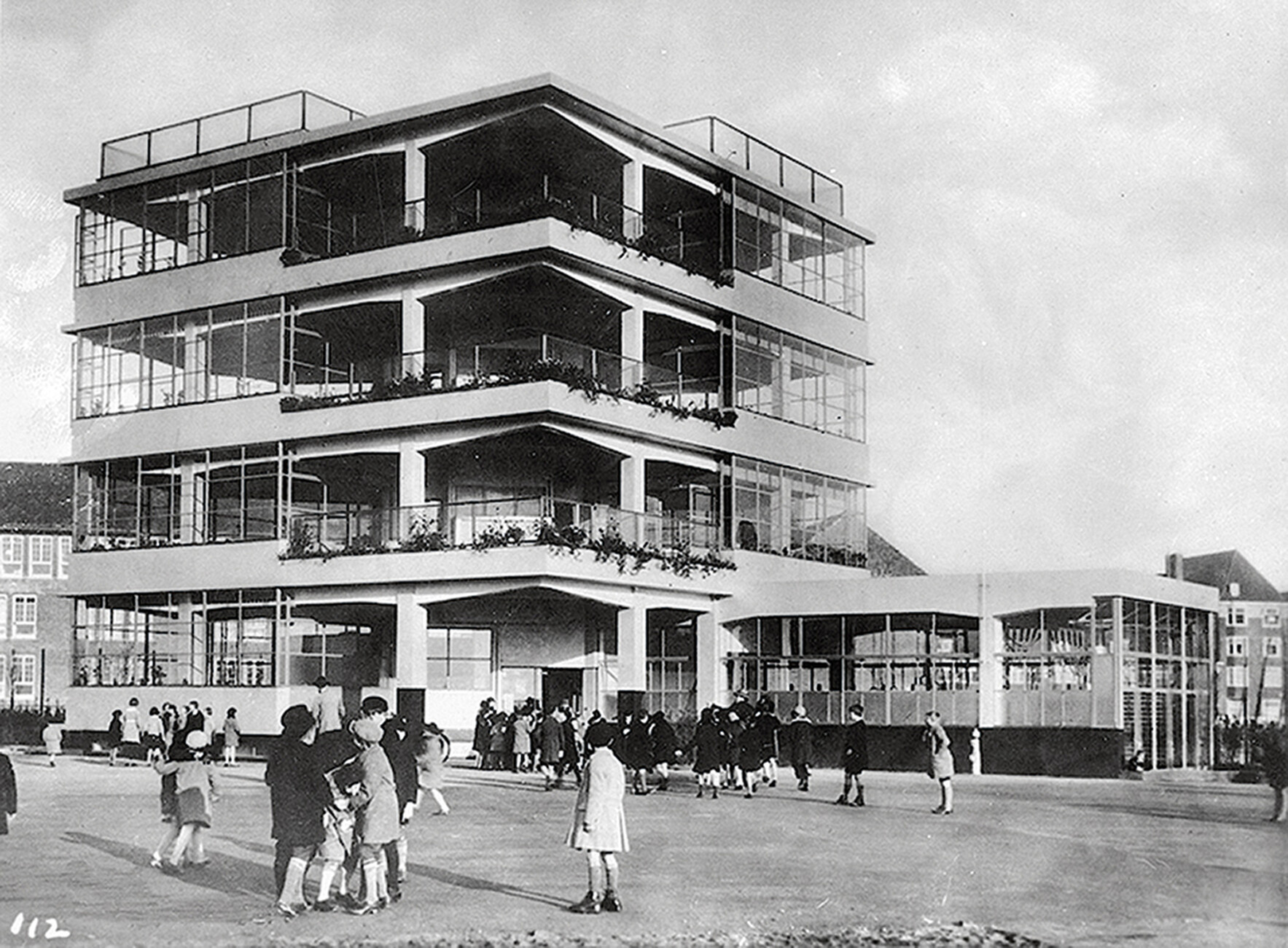

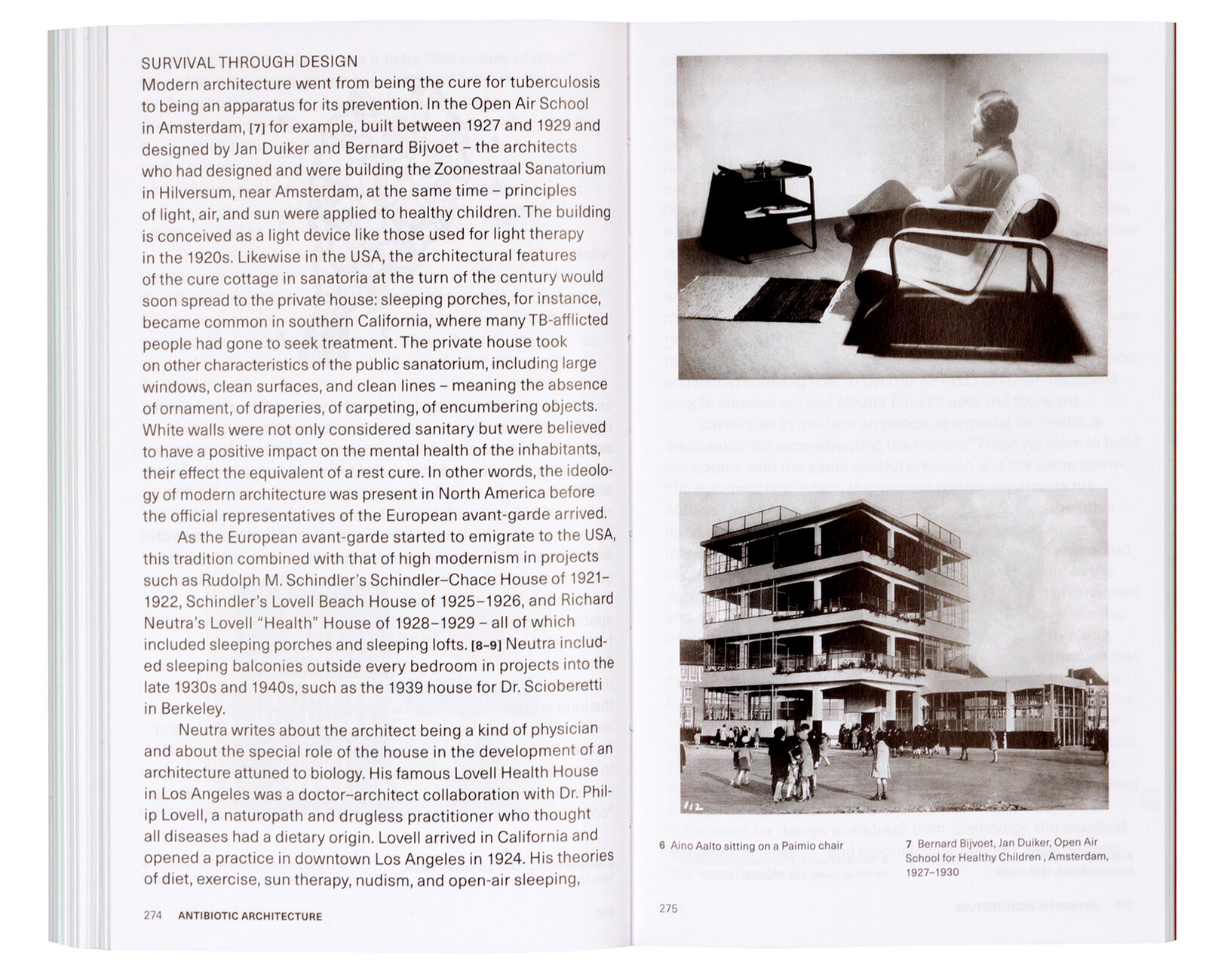

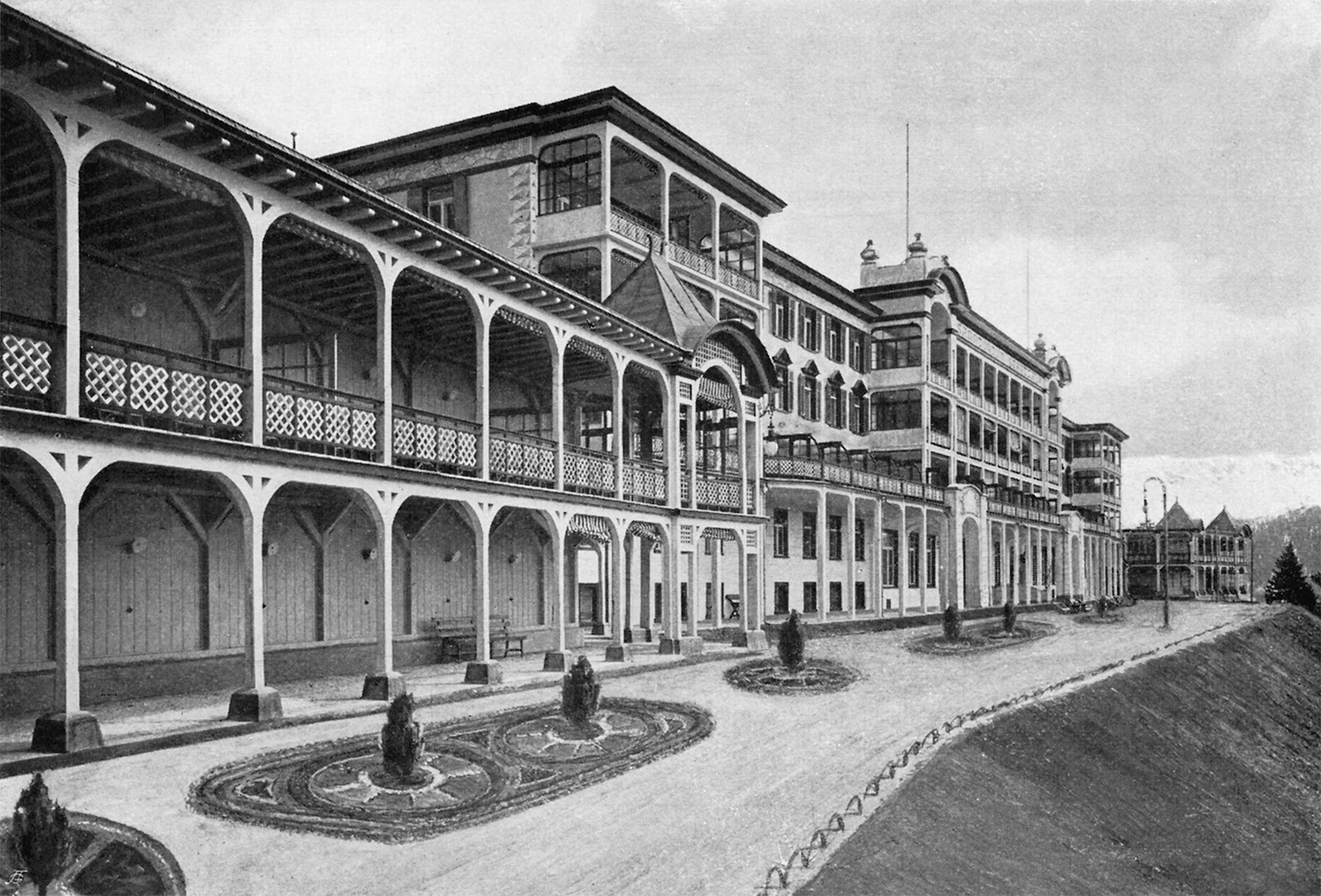

Smooth white walls, simple, easy-to-clean interiors, and architecture that allowed for plenty of daylight and extensive ventilation were once the focus due to the rapid spread of infectious diseases. These were therefore also responsible for the development of a new architectural typology, the sanatorium. This included interior design features specially conceived for this purpose – from indirect light sources, soothing ceiling colors, and upholstered deck chairs to washbasins with surfaces designed to reduce splashing and door handles that doctors' coats could not catch on. A design for the “horizontal human” who spends most of the day lying down. The architect should design for people in the weakest position, Finnish architect and urban planner Alvar Aalto (1898-1976) once stated. In this sense, modern architecture is a medical project.

According to the authors, the Werkbund exhibition “Die Wohnung” (The Apartment), in the context of which the model housing estate “Weißenhof” was built in Stuttgart in 1927 in the style of New Building, was in many ways a health exhibition. A housing estate that not only presented new and affordable solutions for modern city dwellers, but also focused on human health with numerous open-air spaces. At the same time, the furniture design was forward-looking in this respect, from recliners and movable beds to the revolutionary cantilever chair made of tubular steel, which architect Mart Stam presented for the first time at the opening of the Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart, after he had previously devised a clear form using gas pipes. Reduced to the essentials, it conveys the feeling of sitting “on air” as the construction does not require rear legs. This was followed by the cantilever chairs by Mies van der Rohe and Marcel Breuer. “Modern buildings were an active antibiotic that could both cure and prevent disease. What had been tried and tested in sanatoriums became part of everyday architecture,” according to the authors. Consequently, our cities represent a kind of collection of theories of disease from antiquity to the present day.

“We the bacteria: Notes toward Biotic Architecture” is a call for biotic architecture that learns from microbes. Human-centered architecture is unhealthy for humans and countless other species. The authors show how microorganisms could benefit our health in indoor spaces: during the COVID-19 pandemic, microbiologist Elisabetta Caselli and her colleagues used beneficial microbes on the walls of six Italian public hospitals instead of disinfectants. The result was a 90 percent reduction in pathogens and a reduction in resistance genes. According to the authors, the most effective cleaning method is to add microbes rather than remove them. Architecture that promotes biodiversity must itself be biodiverse. One of the most unhealthy features of today's built environment is that it is a monoculture.

Architecture shapes people – Buildings that are designed with life outside in mind improve life inside them, according to the authors. Their conclusion: biotic architecture has many future prospects. And we are only just beginning to understand the world of microorganisms. An exciting read that shows how closely architecture is interwoven with science and provides impetus for a holistic approach.

We the bacteria: Notes toward Biotic Architecture

Authors: Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley

Publisher: Lars Müller Publishers

Paperback

Language: English

352 pages, approx. 319 illustrations

ISBN: 978-3-03778-783-0

2025

20 Euro, 25 USD, 18 GBP